Home | Category: Gods and Mythology / Literature and Drama

PERSEPHONE IN THE UNDERWORLD

Persephone abducted by Hades

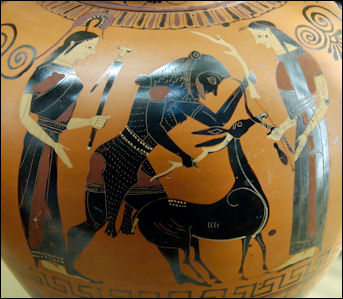

One of the most famous Greek myths is the tale of Persephone, who was kidnaped by Hades, the god of the Underworld , and who is associated with the seasons. Persephone was the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of fertility and harvests and Zeus' sister. She was greatly loved by everyone. She filled Olympus with joy and caused flowers to bloom on earth. One day Persephone wandered from her mother on a visit to earth. She was picking flowers when Hades emerged from the ground with a chariot pulled by black horse and took her to the Underworld and made her the Queen of the Underworld .

Demeter became so distraught at the loss of her daughter she neglected her duties for an entire year. The Earth froze over and a famine ensued, causing untold suffering. Mankind was on the verge of extinction. Demeter eventually enlisted the help of Zeus who convinced Hades to let Persephone go. Persephone was released but there was a problem. While in Hades she ate three pomegranate seeds and no one who had eaten the food of the dead was allowed to leave.

Zeus intervened again and struck a deal with Hades. Persephone was allowed to leave the Underworld but she had to return each year for one month for each pomegranate seed she ate. So each year when Persephone leaves Demeter becomes so depressed that winter ensues. When she is reunited with Persephone in spring, flowers bloom and the world becomes green. To endure the winter months, Demeter taught mankind how to harvest grain and store it during her period of unhappiness.

The Persephone story was used to explain the changing seasons. The abduction is often depicted in Greek art with Persephone being taken away on Hades' chariot, sometimes accompanied by the messenger god Hermes.The Eleusis cult near Athens was dedicated to the worship of Demeter. Special rituals were held to ensure that Persephone returned each spring.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Persephone — Picture Book” for kids Amazon.com;

“Orpheus and Greek Religion” by W. K. C. Guthrie (1935) Amazon.com;

“Underworld Gods in Ancient Greek Religion” by Ellie Mackin Roberts (2022) Amazon.com;

“Greek Heroes In and Out of Hades” by Stamatia Dova (2012) Amazon.com;

“D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths” by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaire (1962) Amazon.com;

“The Complete World of Greek Mythology” by Richard Buxton (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Myths” by Robert Graves (1955) Amazon.com;

“Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes” by Edith Hamilton (1942) Amazon.com;

“Hellenic Polytheism: Household Worship” by Christos Pandion Panopoulos (2014) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East” by Carolina López-Ruiz (2010) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology” by Martin P. Nilsson (1932) Amazon.com;

“Theogony” by Hesiod (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“Metamorphoses” by Ovid, 8 AD (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“Tales from Ovid” by Ted Hughes (1997) Amazon.com;

“Mythos: The Greek Myths Reimagined” by Stephen Fry (2017) Amazon.com;

“Heroes” by Stephen Fry (2019) Amazon.com;

Persephone and Demeter Story

The characters in the story are: 1) Demeter, sister of Zeus and Hades; 2) Hades, Lord of the Underworld; 3) Hecate ('Crone'); 4) Persephone (Kore), daughter of Zeus and Demeter; 5) King Celeus of Eleusis; 6) Queen Metaneira, his wife; 7) Demophon, their baby; 8) Triptolemus, another son; and 9) Iambe and her sisters [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class ++]

return of Persephone

Persephone is abducted while picking flowers in the meadow (symbol of virginity, and its destruction). Hades, in his golden chariot drawn by black horses, 'rapes' her. In Hades' palace, Persephone eats seven pomegranate seeds, and so becomes 'attached' to Hades. ++

Only Arethusa (daughter of Alpheus the River and spring in Sicily), Helios, and Hecate heard or saw the abduction of Persephone. The daughters of Melpomene, who were Pandora's companions, were turned into Sirens because they would not help search for her. While Demeter is searching, there is no fertility (there are similarities between this Isis searching fot the body-parts of her husband-brother Osiris in the Egyptian fertility myth).

Carrying torches, Demeter searches for Persephone. After nine days, Helios (who sees everything above the earth, during the day) tells Demeter where her daughter is. While searching Arcadia Demeter is raped by her brother Poseidon. In Elis, Tantalus prepares a cannibalistic banquet to test Zeus and the gods: his son Pelops is the dinner. The other gods perceive the trick, but Demeter is so distracted that he eats Pelops' shoulder. Although Pelops is reassembled and reanimated by Zeus (again there are similarities to the resurrection in the Osiris story). His shoulder is replaced by a carved piece of ivory. ++

Taking the form of an old woman (Crone), Demeter sits down to rest near a well called Parthenion (‘Maiden'), where she is approached by the daughters of King Celeus, who have come to fetch water. John Adams of CSUn wrote: “They treat the disguised goddess sympathetically, and invite her to come to the Palace, since their mother needs a nanny for their young brother. The most amusing of the girls is Iambe (‘Iambic verse’). Offered hospitality, Demeter refuses wine, but accepts a drink called kykeion (barley water with pennyroyal). Queen Metaneira is impressed with the ‘woman' and gives her employment. Demeter anoints the baby Demophon every evening with ambrosia, and puts the baby in the fire of the hearth to burn away its mortality. But one evening Metaneira spies on Demeter and interrupts the rite. Demeter drops the child in surprise, resumes her divine form, and rebukes Metaneira for interfering with divine secrets which would have made the baby immortal. But Demeter does promise to teach her sacred rituals to the Eleusinians. ++

On the intervention of the older Earth-goddess Rhea (grandmother crone), Demeter (mother) is reconciled with Zeus (father) and Hades (husband), and has her daughter Persephone (‘Maid') restored to her — at least part-time. ++

Demeter teaches King Celeus' son Triptolemus to cultivate wheat (there is a sacred field of grain at Eleusis, the Riarian Field). He becomes the ancient version of Johnny Appleseed, spreading the knowledge of wheat-cultivation. In Scythia (the Ukraine he visits King Lynkos (‘The Lynx'), who tries to murder Triptolemus so that he can become the sole possessor of the secret of wheat, and therefore its patron/manipulator. Demeter intervenes, however, and turns Lynkos intoa lynx (Ovid, Metamorphoses V. 648 ff.) ++

Orpheus

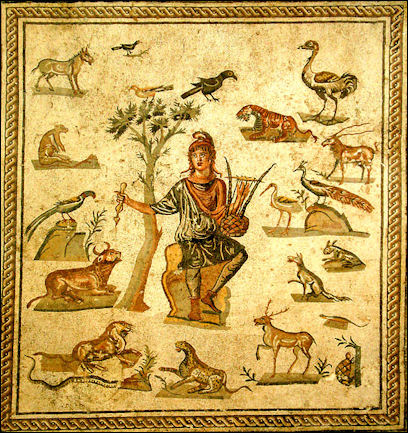

Orpheus Orpheus is a Thracian and came from the same area, near Mount Pangaeus, as Dionysus' enemy Lycurgus and Heracles' foe Diomedes and his cannibalistic horses. Said to be a son of Apollo and Calliope (The Muse from the Myrrha and Adonis story), or the son of Oeagrus, a king, he was an early follower of Dionysus, but later turned against human and blood sacrifices. He was also a noted musician and lyre-player (Apollonian traits) and a magician. It was said he could charm the birds out of the trees (similar stories were later attributed to St. Francis of Assisi, St. Anthony of Padua and the fishes) and even make trees dance.[Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Orpheus went on the expedition with Jason and the Argonauts. On the way to Colchis, he introduced Heracles and the Argonauts to the ‘Samothracian Mysteries'. On the way back, he helped the crew to avoid the Sirens (from the Demeter and Persephone story) by covering their seductive but deadly sounds with his lyre playing.

Orpheus famously married Eurydice: (a nymph, either a Naiad or a Dryad). Shortly after her marriage she is chased through a field, where she was gathering posies, by Aristeas (the ‘Bee-Man') (Vergil, Georgics Book IV). A serpent lurking in the grass (the original snake-in-the-grass) bites her and she dies, and descends to the House of Hades, the Underworld. Orpheus descends to the House of Hades to try to rescue her, using the entrance at Tenaerum in Laconia (Sparta). Hades and Persephone agree to allow Eurydice (‘wide-judging') to go, if Orpheus can keep from looking at her until she is above ground again. He fails, and Eurydice has to return to Hades.

Orpheus returns to Thrace, where he is destroyed by native Thracian girls (of the Ciconian tribe), for one of the following reasons: a) He switched to boys exclusively after his failed marriage; 2b) He had not properly honored Dionysus, whose devotees they were (Maenads, Bacchae, Bacchantes); c) Aphrodite inspired the Ciconian women because of Calliope's judgment in favor of Demeter in the Adonis incident; or d) The Ciconian women each wanted him, and they ripped him apart (thereby making him the patron saint of rock stars).

The Muses buried Orpheus in their home in Pieria (where Apollo kept his cattle, and the royal Macedonian capital of Aegae was), except for his head. At his resting place (Libethra), near Mount Olympus, it is said that the nightingales sing more sweetly than any place else in the whole wide world. The head of Orpheus floated down the Hebrus (or is it the Haliacmon) River and out to sea. It turned up on the beach of the island of Lesbos, where an oracle of Orpheus was founded at Antissa. His lyre was placed in the sky by the gods, and became the constellation Lyra.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus was the son of Apollo and the muse Calliope. An Argonaut in his youth, he overcame the narcotic effect the Sirens by shaking his men alert so they regained their wits and rowed to safety.

Eurydice was a "nymph" who lived in the forest and hunted with the goddess Diana, feasted with Dionysus and spent time with mortals. Orpheus fell in love her. After they got married Eurydice was kidnapped by Aristaiois (one of Apollo's sons) but escaped only to be killed by a bite from a snake. Orpheus found her and vowed to go Hades, the Underworld , and bring her back.

Orpheus descended to Hades with a lyre and played a song that was so sad the cave spirits felt pity and let him pass unmolested. Charon ferried him across the River Styx and even Cerbus, the three headed dog, with hair of snakes, left him alone. Finally he met the king and queen of the Underworld and persuaded them to let him take Eurydice back to the world. But there was one catch here too: he couldn't look back to see her until they entered the light.

On the journey out of the Underworld Orpheus was filled joy. When he emerged from a cave into the light he was so overjoyed he turned around almost immediately. But he did so too soon. Eurydice had not stepped into the light yet and he lost her forever. She fell back into the cave, crying "Farewell."

Orpheus entered Hades again but was unable to win Eurydice's release. He returned to the Earth and played his lyre for the plants and animals and was ultimately torn limb from limb and beheaded by the female followers of Dionysus because he failed to join their orgies. The story ends with Orpheus lyre plying itself and his severed head singing its sad song.

Herakles (Hercules)

Hercules Hercules (Herakles to the Greeks and Hercules to Romans) is most popular and celebrated of the Greek heros. He was the son of the mortal Alcmene, who made love to Zeus and her husband on the same night and bore two children: Hercules son of Zeus and Iphicles, son of her husband Amphityon. Hera was angry about her husband’s indiscretion and vented her anger at Hercules.

Hercules inherited great strength from his father and began performing heroic deeds at an early age. When Hera place had two serpents placed in his cradle Hercules grabbed them and strangled them. As he was growing up he was trained in the arts of war by Centaurs and heros. When he was a young man two women sought him out. Kakia (vice) promised him an easy life of luxury and wealth if he followed her. Arete (virtue) promised him only glory from fighting evil if he followed her. Hercules followed the latter.

Marianne Bonz wrote for PBS’s Frontline: “According to Greek legend, Herakles was the son of Zeus by a mortal woman of noble lineage, whose name was Alcmene. Zeus's vengeful wife, Hera, attempted to kill the infant Herakles by placing serpents in the cradle where he and his twin brother slept. But Herakles strangled the snakes, thus saving himself and his twin. [Source: Marianne Bonz, Frontline, PBS, April 1998. Bonz was managing editor of Harvard Theological Review. She received a doctorate from Harvard Divinity School, with a dissertation on Luke-Acts as a literary challenge to the propaganda of imperial Rome.]

“In addition to semi-divine parentage and birth in difficult circumstances, another common feature of the lives of demi-gods is that they encounter ignominy or great misfortune, which they must either overcome before death or resolve through death. After he was grown and married, Herakles was struck with a deadly madness and, mistaking his own wife and children for those of a bitter enemy, he killed them. It was in atonement for this terrible crime that he performed the twelve superhuman labors that rid the world of terrifying monsters and brought new security to the world's inhabitants. Because of his superhuman strength, Herakles was the patron of athletes, and sanctuaries honoring him adorned virtually every gymnasium throughout the Greco-Roman world. But his most important role was that of powerful patron and protector of human beings and gods alike.

See Separate Article: HERAKLES (HERCULES) AND HIS TWELVE LABORS: 174 europe.factsanddetails.com

Jason and the Argonauts and the Golden Fleece

Jason and the Argonauts was the first nautical saga in Western Literature. Many of the events in the 3000-year-old story also took place in present-day Turkey and Georgia. The plot of the saga was this: Jason left Greece with a boat load of heroes — including Hercules, the twins Castor and Polux, and Orpheus — on a journey to Colchis (present-day Georgia) on the Black Sea to claim the Golden Fleece that came from a golden ram that long time ago carried a young Greek prince across the Black Sea to safety. Jason’s ship, the 50-oar “Argo”, contained a beam cut from the divine Dodona tree that could tell the future. Teeth of the sleepless serpent when sowed grew into armed soldiers. ["Jason's Voyage" by Tim Severin, September 1975 (⊛)]

Route of Jason and the Argonauts

Claiming the Golden Fleece was regarded as an impossible task. It hung in a sacred grove guarded by an enormous serpent. If Jason managed to bring it home he could reclaim his rightful place on his father’s throne taken from him by his uncle Pelias. For thousands of years gold dust has been extracted from the rivers draining the Caucasus area by placing sheepskins on the stream bottom to trap particles. The expression the golden fleece is believed to have possibly been derived from this practice.

On his journey to Colchis Jason was challenged by a barbarian in the Aegean Sea to a boxing match to the death; he was given directions in the Sea of Marmara by a blind prophet tormented by Harpies; and the crew was beguiled by women on island without men. After barely making it through the Bosporus, the “Argo” was almost swallowed by vessel-eating rocks in the Black Sea. But finally Jason and the Argonauts made it to his destination.

After reaching Colchis, the Argonauts sailed up the River Phasis. In Colchis, Jason was given a number of tasks by King Aettes, the king of the Cochians. These including putting yokes on dangerous bulls, plowing fields where dragon teeth grew into dragons and killing the sleepless snake that guards the fleece. Jason claimed the fleece, with the help of Medea, a princess who betrayed her family, by drugging the serpent. With the fleece in hand and the princess's father ships in pursuit Jason headed back to Greece where he claimed his throne. The story's postscript unfortunately is not a happy one. Jason later married another woman and the princess from Colchis got revenge by poisoning his bride and their children.⊛

Jason and the Golden Fleece is a story of heroism, treachery, love and tragedy. It features a classic triangle of hero, dark power and female helper, a form still very much alive in Hollywood films.The Argonauts are named after their ship, the Argo, designed by Athena. Jason, son of Aeson and Polymede, of Iolcus, was captain. Tiphys, son of Hagnias, was helmsman.

See Separate Article: JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS europe.factsanddetails.com

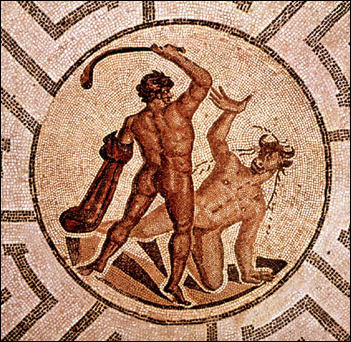

Minotaur, Theseus and the Labyrinth

Theseus was another great Greek hero. The son of the King of Athens, he was raised in a distant land and didn’t arrive in Athens until he was a young man strong enough to lift a stone under which his father placed a sword and a pair of sandals. After becoming King of Athens he fought with Centaurs and battled Amazons

Theseus_Minotaur mosaic The story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth, according to to some, is set in Crete, presumably during the Minoan era. According to legend, King Minos was a wise leader and a just lawgiver who ruled Crete from Knossos and lived in a magnificent palace. One day the sea-god Poseidon gave him a magnificent white bull that was intended to be sacrificed in the sea god's honor. Minos greedily kept the bull instead and Poseidon got even with the king by casting a spell on his wife, which made her want to make love with the bull, which she did, producing the Minotaur. Daedalus, the Athenian architect who later tried to fly to Sicily with wings made of wax, built the Labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur.

After King Minos's son was killed in Athens the king captured Athens and secured an annual tribute of seven youths and seven virgins to be eaten by the Minotaur. One of youths offered to the Minotaur — Theseus — fell in love with King Minos's daughter. Daedalus gave Theses a ball of string so that he could find his way out of the labyrinth of he managed to kill the Minotaur. After slaying the Minotaur Theseus fled Crete with king’s daughter but as was true with heros in other Greek myths, such as Jason from the Argonauts, Theseus abandoned the girl after winning his freedom.

The Minoans believed that King Minos was the son of Europa, the daughter of King Sidon, and Zeus transformed into a bull. The association of the Minotaur myth with Knossos can be traced to Sir Arthur Evans, the British adventurer, who excavated Knossos in the 1890s. He reportedly was struck by the size of Knossos and its large number of rooms that he figured it must be the source of the labyrinth myth. Some have said he defied one of the cornerstones of archaeology by forcing evidence to fit his model rather than letting evidence speak for itself. Evans is also the source of some other dubious claims about Minoa.

See Separate Article: THESEUS AND THE MINOTAUR europe.factsanddetails.com

Daedalus and Icarus

Icarus After rescuing Theseus from the Minotaur Daedalus made some wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape Crete. Daedalus became inspired to make a flying machine after watching the witch Medea take off in a fiery chariot pulled by five dragons. After observing the flight patterns of eagles, Daedalus devised wings made from eagle feathers and a special wax.

When Icarus was a child, Daedalus devised intricate toys’such life-size robots and games with 7,000 different cards — to amuse himself with. When Icarus saw the wings he wanted to try them right away but Daedalus wanted to make some flight test before taking the skies. But events in Minoa made him change his mind.

After it was discovered that Daedalus allied himself with Theseus, king of Attica, to overthrow King Minos and defeat the Minotaur, Daedalus and Icarus were forced to make a quick escape and they donned their wings. Icarus, according to legend, flew too high and the wax on his wings melted but Daedalus made it to Italy.

Daedalus is considered the "inventor" of the art of sculpture. He created the art on the island of Sicily after he escaped the Labyrinth with his wax and feather wings. The legend is probably based on a real-life Daedalus who lived in Crete in the 7th century B.C. and was known for his craftsmanship. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Recreating Icarus's Flight

In the summer of 1988 a Greek cyclist and a team of engineers and students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology attempted to recreate the flight of Daedalus in a human powered aircraft. If you recall Daedalus made it to Italy. Italy was too far away for the MIT team so for their attempt they chose Santorini which is 27 miles away.¶

“Daedalus” , not surprisingly, was the name they chose for their human powered aircraft. The frame of the aircraft was made from super light, super stiff graphite epoxy that was layered and shaped and baked in an oven. The hollow 112 foot main wing tube was the thickness of a dime. The wing itself was made of polystyrene foam ribs covered the ultra thin Mylar plastics. Holding at all together was Kevlar yarn and a few metal screws. Pieces of metal were drilled out to conserve weight and even the glue was weighed to produce the 68.5 pounds craft.

The 11 foot propeller turned 105 revolutions per minute to reach a speed of 21 miles per hour or "Mach .03" one MIT student observed. To fly the craft the 27 mile distance from Crete to Santorini would take the same amount of energy as pedaling a racing bike 23 miles an hour for six hours. The man chosen to fly the craft was Kanellos Kanellopoulos, 14 time Greek cycling champing. He trained by riding 60 to 100 miles a day and nourished himself on 7000 calories day. On the day of the flight he wore cycling shorts sliced up with dozens of small holes to "show the extreme measures taken to conserve energy."

After waiting around for weeks for the wind to die down enough to make the flight possible, “ Daedalus “ took off at 7:03am on April 23, 1988. As Kanellopoulos soared at a speed of 14 knots, 50 feet above the water, he exclaimed "It better than perfect!" At 8:29am he had flown 23 miles, a new distance record, and at 9:52 he broke the record for time aloft...but he didn't quite make it to Santorini. Just as he neared the black sand shore of the island a gust of wind hit the aircraft splintering the graphite tail boom and braking the right wing spar. Kanellos freed himself from his pedals and escaped from the craft when it gently hit the water. He came up out of the water with a smile. “ Daedulus” was in the air for 3 hours, 54 minutes and 59 second and although it landed 50 feet short of it destination everyone felt it had triumphed.

Perseus and the Medusa

Medusa Perseus was the son of Zeus and Danae, the beautiful daughter of the evil king of Argos. The king had banished Danae and Perseus from his kingdom because of an oracle that predicted his son would kill him. Danae and Perseus ended up on an island with a king who desired Danae but figured the only way to get her was to get rid of Perseus by sending him on an impossible task: to bring back the head of the Medusa.

The Medusa was one of the three Gorgons, horrid sisters with bat-like wings, fierce claws and poisonous snakes hissing from their heads. One look from the sisters could turn a man to stone. The king thought that Perseus would probably die in his effort. But Theseus had the gods on his side. Athena gave him a hughly polished shield. Hermes gave him a magic sword and special winged sandals. Pluto gave him a cape of darkness, which made him invisible.

On his journey to the land of the Gorgons Perseus encountered the three Gray Sisters, who had only one eye between them. He stole their eye and refused to give it back until the sisters told him where to find the Gorgons. With their directions Theseus came upon the Gorgons while they were sleeping. Putting on the cloak of darkness he approached them. Using the polished shield as a mirror, so he wouldn’t have to look at them directly Theseus cut off the head of the Medusa with the sword and escaped with the help of the winged sandals. Later with his magic sword Perseus killed a sea monster and saved the beautiful Andromeda. They fell in love. At the wedding an old boyfriend tried to claim Andromeda. Perseus turned him stone by holding up the head of the Medusa.

Debra Kelly wrote in Listverse: What’s rarely mentioned is that Medusa wasn’t the only snake-haired woman. Medusa is the only mortal of three sisters, and all of them were Gorgons. Her sisters, Stheno and Euryale, were immortal Gorgons with the same hideous appearance as Medusa. They were all the daughters of Phorcys, a sea god, and his sister, Ceto, and they served as guardians to the underworld. In addition to having snakes for hair, the Gorgons were also said to have powerful brass hands, scales, and beards. Today, we only remember Medusa’s name because she’s the only Gorgon that Homer speaks of in his works. [Source Debra Kelly, Listverse, December 17, 2013]

Hero, Leander and Byron

Hero and Leander

Hero was a priestess of Aphrodite. She lived on the European side of the Hellespont (the Dardanelles) a 38-mile-long strait between the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara that is less than a mile across in some places. At a festival she met Leander, who lived on the Asian side of the strait. They fell in love. Every night he would swim across the Hellespont to see her, guided by a torch she held out for him. One night a terrible storm blew in. The torch blew out and Leander, not able to see his way, got lost and drowned. Hero found his body on the shore. Unable to bear the grief, the broken-hearted Hero threw herself into the sea and drowned as well.

On May 3, 1810, the famous English poet Lord Byron, who lived briefly next to the Dardanelles, duplicated Leander’s swim across the Hellespont. The distance is only a mile but the current was so strong that Byron doubted "whether Leander's conjugal power must not have been exhausted in his passage to Paradise." He later wrote of the experience, "I plume myself on this achievement more than I could possibly for any kind of glory, political, poetical, rhetorical."

King Midas and the Golden Touch

King Midas was the famed monarch with the golden touch. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: There were three historical members of the Phrygian monarchy known as Midas. The most famous is associated with wealth and, in particular, gold. According to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Midas acquired his powers as a gift from the god Dionysus (also known as Bacchus) for offering Dionysus’ foster father Silenus hospitality. Silenus had wandered off in a drunken stupor and found himself at the court of King Midas, where he spent 10 days drinking and regaling the court with stories. When Silenus returned to Dionysius, Dionysius told Midas he could choose his own reward. Midas hastily responded that he wanted anything he touched to turn to gold. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 12, 2020]

The problem, of course, was that Midas was unable to eat anything. In Ovid’s version a distraught and hangry Midas begs Dionysus for help and the ‘gift’ is revoked. In the 19th century children’s version written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Midas accidentally turns his own daughter into gold. Aristotle is less forgiving and writes in his Politics that Midas’s insatiable greed led to his death from starvation. In all three versions the lesson is clear: wealth is less important than family and food.

Other versions of the Midas story also have him dying in unpleasant ways. According to Hyginus, the Roman-era author of a collection of fantastic tales called the Fabulae, Midas didn’t learn much from his run-in with Dionysus. After losing his alchemical powers he became a devotee of the half-goat deity Pan. In a musical contest between Pan and Apollo, Midas foolishly pronounced that Pan was the winner. The incensed Apollo punished Midas by turning his ears into those of a donkey. Unable to conceal his disfigurement, Midas committed suicide by drinking bull’s blood.

If dying in this way seems improbable, bear in mind that bull’s blood was thought to have killed an Athenian politician, an Egyptian pharaoh, and, of course, Midas. Ancient medicine held that ox blood congealed more quickly than other forms of blood so drinking it would result in death by choking. In her book Gods and Robots, Adrienne Mayor notes that bovine thrombin (the blood-clotting enzyme) has been used in surgery since the 1800s and that it, in fact, still sometimes carries the risk of a “fatal cross reaction.”

None of these were happy ways to die, but when it comes to burial places, Midas had it pretty good. An enormous tomb in Gordium (modern Yassihüyük, Turkey), the capital of the ancient Phyrgian empire, has been identified in the modern period as the tomb of King Midas. Also known as the Great Tumulus, the vast tomb was clearly built for a man of great importance, although it is unclear if that man was actual Midas. If it is his tomb then we may even have a sense of Midas’s physical appearance from the remains of the person buried there. A reconstruction of the face of the skull from the Great Tumulus is on display at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

If there’s a moral to these stories it is surely this: careful what you wish for, steer clear of ox’s blood, and monuments to even the greatest conquerors end up buried in ditches.

Phrygian — the Home of King Midas and The Gordian Knot

the Nathaniel Hawthorne version of the Midas myth, when Midas touches his daughter she turns to a golden statue

The Phrygian Highland (north of Afyon in central Turkey) is region once inhabited by the obscure Phrygian kingdom of King Midas. Gordion (south of Ankara) was site of the former Phyrgian capital and where Alexander the Great "solved" the famous puzzle of the Gordium's knot by severing it with blow from his sword. According to legend whoever undid the intricately twisted knot would become the ruler of Asia.

The great earth burial mound of King Midas, the man with golden touch, is located here. The tomb dates to 718 B.C. based on the dated of tree rings in the juniper logs used in the burial chamber, which is regarded by some as the oldest wooden structure in the world.

It is not known for certain if the tomb really belongs to King Midas but there is a good chance it does (dates of the tomb match written references to King Midas in Assyrian records, the tomb’s size indicated it belonged to someone important). The largest of 80 Phrygian tombs in the region, the tomb was 175 feet high and 100 feet in diameter. Erosion has taken away 55 feet. Work on the tomb is believed to have continued long after death of the occupant. The low moisture content, stable environment of the surroundings preserved items inside.

Deep within the mound was a 17-x-20-foot pine chamber encased with wooden timbers excavated in 1955 and 1956 by Rodney Young of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Object recovered included drinking vessels, lion- and ram-headed situla (buckets) used in the funerary feats, elaborate inlaid furniture, a serving table described as the world’s oldest piece of inlaid furniture, pottery bowls, large metal cualdrons on iron stands, textiles, 100 bronze bowls, but no gold. . The first people inside they tomb said they smelled stew.

Analysis of the remains revealed a clean-shaved man, with a protruding lip and skull flattened on the back, who died when he was between 60 and 65. The protruding lip and flattened skull may have been the result of accidents. The tomb occupant was five-foot-two and wore leather pants. His body was found in a coffin cut from a cedar log and placed on a pile of textiles and wooden bed. The tomb had no door. The coffin and bed and other items had to be taken apart to be lowered into the tomb and then reassmbled,

In side the tomb were remains of Phrygian feast with strong grape wine, barely beer and mead, goat and sheep stew made with lentils, olive oil, wine, fennel, honey and spices. Today the juniper log burial chamber tomb can be reached by a tunnel through the burial mound. Many of the best artifacts are at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. Artifacts in the Gordion Museum include a mosaic floor dated to 750 B.C., decorative saftey pins, numerous bronze bowls designed for finger scooping; cermaic cups; a small bone flute; and clay statuetes of the Phrygian mother earth goddess

Evidence of King Midas’ Downfall?

In 2020, archaeologists in Turkey announced they may had finally identified tangible historical evidence linked with the demise of King Midas, of "Midas Touch" fame, on the Konya Plain in the southern part of the country. The discovery was made a farmer told who told researchers about a strange inscribed stone that was half-submerged in irrigation canal. The stone block recorded information about a 3,000-year-old victory. The the stele dates to the end of the eighth century B.C., the period when King Midas lived

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The stone itself was discovered and translated in the summer of 2019 by scholars from the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute as part of an international project to survey a large Bronze and Iron Age settlement (3500-100 B.C.) in Türkemn-Karahöyük. Archaeologists knew that the settlement was an unexcavated ancient city, but they didn’t know its historical significance or even who had lived there. The stone, which contained ancient writing, had the potential to change things. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 12, 2020]

Chicago professor James Osborne described how he rushed to the canal and waded in waist-deep water looking for the stone. “Right away,” he said, “it was clear that the stone was an ancient artifact.” They instantly recognized the inscription as Luwian (a hieroglyphic language used in the region during the Bronze and Iron Ages) and set about trying to remove the block from the water.

Once the stone was dragged out of the irrigation canal by tractor, cleaned, and photographed, Osborne and his Oriental Institute colleagues got to work on translating the partially eroded inscription. They realized that it was an announcement of King Hartapu’s military victory over the neighboring kingdom of Phrygia (identified in the stone block, or stele, as Muska), the ancient kingdom that was ruled over by King Midas. According to the translation, “The storm gods delivered the [opposing] kings to his majesty [Hartapu].” Linguistic analysis determined that the stele was probably created in the late eighth century B.C., when Midas ruled in Phrygia.

Osborne thinks that the city at Türkemn-Karahöyük, which was one of the largest ancient cities in the period, was the capital city of King Hartapu. Hartapu himself was, until this discovery, very much a mystery to scholars. He was a late Hittite king who was known to us from inscriptions, but no one was certain where his kingdom actually was. Now, it seems, we know where his kingdom was based even if we still don’t know exactly what it was called.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024