Home | Category: Gods and Mythology / Literature and Drama

JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS

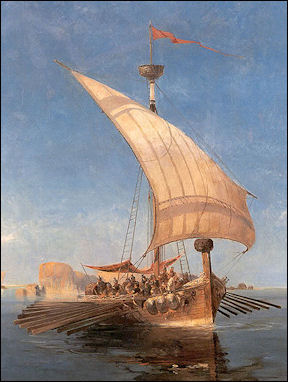

Jason and the Argonauts Jason and the Argonauts was the first nautical saga in Western Literature. Many of the events in the 3000-year-old story also took place in present-day Turkey and Georgia. The plot of the saga was this: Jason left Greece with a boat load of heroes — including Hercules, the twins Castor and Polux, and Orpheus — on a journey to Colchis (present-day Georgia) on the Black Sea to claim the Golden Fleece that came from a golden ram that long time ago carried a young Greek prince across the Black Sea to safety. Jason’s ship, the 50-oar “Argo”, contained a beam cut from the divine Dodona tree that could tell the future. Teeth of the sleepless serpent when sowed grew into armed soldiers. ["Jason's Voyage" by Tim Severin, September 1975 (⊛)]

On his journey to Colchis Jason was challenged by a barbarian in the Aegean Sea to a boxing match to the death; he was given directions in the Sea of Marmara by a blind prophet tormented by Harpies; and the crew was beguiled by women on island without men. After barely making it through the Bosporus, the “Argo” was almost swallowed by vessel-eating rocks in the Black Sea. But finally Jason and the Argonauts made it to his destination.

After reaching Colchis, the Argonauts sailed up the River Phasis. In Colchis, Jason was given a number of tasks by King Aettes, the king of the Cochians. These including putting yokes on dangerous bulls, plowing fields where dragon teeth grew into dragons and killing the sleepless snake that guards the fleece. Jason claimed the fleece, with the help of Medea, a princess who betrayed her family, by drugging the serpent. With the fleece in hand and the princess's father ships in pursuit Jason headed back to Greece where he claimed his throne. The story's postscript unfortunately is not a happy one. Jason later married another woman and the princess from Colchis got revenge by poisoning his bride and their children.⊛

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Argonautica” (Penguin Classics) by Apollonius of Rhodes Amazon.com;

“Jason and the Argonauts” (Penguin Classics) by Apollonius of Rhodes (2014) Amazon.com;

“Argonautika: The Voyage of Jason and the Argonauts”, Illustrated, by Mary Zimmerman (2013) Amazon.com;

“D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths” by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaire (1962) Amazon.com;

“The Complete World of Greek Mythology” by Richard Buxton (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Myths” by Robert Graves (1955) Amazon.com;

“Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes” by Edith Hamilton (1942) Amazon.com;

“Hellenic Polytheism: Household Worship” by Christos Pandion Panopoulos (2014) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“Mythos: The Greek Myths Reimagined” by Stephen Fry (2017) Amazon.com;

“Heroes” by Stephen Fry (2019) Amazon.com;

Argonauts

Jason and the Golden Fleece is a story of heroism, treachery, love and tragedy. It features a classic triangle of hero, dark power and female helper, a form still very much alive in Hollywood films. The Argonauts are named after their ship, the Argo, designed by Athena. Jason, son of Aeson and Polymede, of Iolcus, was captain. Tiphys, son of Hagnias, was helmsman.

The other argonauts, according to one list, were: 1) Orpheus, son of Oeagros (or Apollo); 2) Castor, son of Tyndareus, of Sparta; 3) Polydeuces [Pollux], son of Zeus, of Sparta; 4) Zetes, son of Boreas; 5) Calais, son of Boreas; 6) Telemon, son of Aeacus; 7) Peleus, son of Aeacus; 8) Heracles, son of Zeus [did not complete journey]; 9) Theseus , son of Aegeus, of Athens and Troezen; 10) Idas, son of Aphareus; 11) Lynceus, son of Aphareus; 12) Amphiareus, son of Oicles; 13) Coronus, son of Caeneus; 14) Palaemon, son of Hephaestus [or Aetolus]; 15) Cepheus, son of Aleus; 16) Laertes, son of Arceisius; 17) Autolycus, son of Hermes; 18) Atalante, daughter of Schoeneus; 19) Menoetius, son of Actor; 20) Actor, son of Hippasus;

21) Admetus, son of Pheres; 22) Acastus, son of Pelias; 23) Eurytus, son of Hermes; 24) Meleager, son of Oeneus; 25) Ancaeus, son Lycurgus; 26) Euphemus, son of Poseidon; 27) Poeas, son of Thaumacus; 28) Butes, son of Teleon; 29) Phanus, son of Dionysos; 30) Stalphylus, son of Dionysos; 31) Erginus, son of Poseidon; 32) Periclymenus, son of Neleus; 33) Augeas, son of Helios; 34) Iphiclus, son of Thestius; 35) Argus, son of Phrixus; 36) Euryalus, son of Mecisteus; 37) Peneleos, son of Hippalmus; 38) Leitus, son of Alector; 39) Iphitus, son of Naubolus; 40) Ascalaphus, son of Ares; 41) Ialmenus, son of Ares; 42) Asterius, son of Cometes; 43) Polyphemus, son of Elatus.

History of the Jason and the Golden Fleece Story

Pelias sending forth Jason

The earliest complete descriptions of Jason’s adventures come from the “Argonautica”, an epic poem composed in the 3rd century B.C. by the Hellenistic poet Apollonius Rhodius. The unhappy ending was added later. But Rhodious’s poem is not the first to mention Jason’s journey. The Argonaut legend is among the oldest known in the Greek world. Homer alluded to it the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” . Some of the participants in the Trojan War were described as the sons and grandsons of the Argonauts, which would placed the Argonaut’s story about 30 to 75 years before the Trojan Wars which are thought have taken place around 1200 B.C. [Source: Kristin Romey, Archeology magazine, March/April 2001]

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “The Greek tale of Jason and the Golden Fleece has been told for 3,000 years. It's a classic hero's quest tale - a sort of ancient Greek mission impossible - in which the hero embarks on a sea voyage into an unknown land, with a great task to achieve. He is in search of a magical ram's fleece, which he has to find in order to reclaim his father's kingdom of Iolkos from the usurper King Pelias. [Source: Michael Wood, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The story is a set a generation before the time of the Trojan War, around 1300 B.C. but the first known written mention of it comes six centuries later, in the age of Homer (800 B.C.). The tale came out of the region of Thessaly, in Greece, where early epic poetry developed. The Greeks have retold and reinterpreted it many times since, changing it as their knowledge of the physical world increased. |::|

“No one knows for sure where the earliest poets set the adventure, but by 700 B.C. the poet Eumelos set the tale of the Golden Fleece in the kingdom of Aia, a land that at the time was thought to be at the eastern edge of the world. At this point the Jason story becomes fixed as an expedition to the Black Sea. The most famous version, penned by Apollonius of Rhodes, who was head of the library at Alexandria, was composed in the third century B.C. after the invasion of Asia by Alexander the Great. |::|

“Since the 1870s a series of excavations at Mycenae, Knossos, Troy and elsewhere has brought the Greek Heroic Age - the imaginary time when the great myths were set - to life. The archaeologists' discoveries of Bronze Age (2300-700 B.C.) artefacts made it clear that the Greek myths and epic poems preserve the traditions of a Bronze Age society, and may refer to actual events of that time. The story could also perhaps represent an age of Greek colonisation around the shores of the Black Sea. |::|

And it seems possible that hero, dark power and female model was based on an even earlier myth. An excavation of the 1920s and 30s, at Boghaz Koy, in central Turkey, uncovered Indo-European tablets from a Hittite civilisation dating to the 14th century B.C. . One of these has an account on it of a story similar to that of Jason and Medea, and may reveal the prehistory of the myth. It is not known at what date the Greeks borrowed it, but it very possibly happened in the ninth or eighth century B.C. . This was the time when many themes were taken from the east and incorporated into Greek poetry. |::| In villages in the Svaneti region of northwest Georgia, people still pan for gold using the fleece of a sheep. The first stop of the Argonauts was Lemnos, a real place. In the story it was populated entirely with women

Route of Jason and the Argonauts

Archeology, Herodotus and Recreating the Trip of Jason and the Argonauts

There is little archeological evidence to support the existence of Colchis and Greeks in the region in the 13th century B.C. but there is evidence of Greeks in Colchis from the mid 6th century B.C. onward. Some historians and archeologist believe the Argonauts myth reflects the earliest Greek explorations even though there is no physical evidence that the Greeks were exploring the Black Sea in 13th century B.C.

The fifth century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: For the people of Colchis are evidently Egyptian, and this I perceived for myself before I heard it from others. So when I had come to consider the matter I asked them both; and the Colchians had remembrance of the Egyptians more than the Egyptians of the Colchians; but the Egyptians said they believed that the Colchians were a portion of the army of Sesostris. That this was so I conjectured myself not only because they are dark-skinned and have curly hair (this of itself amounts to nothing, for there are other races which are so), but also still more because the Colchians, Egyptians, and Ethiopians alone of all the races of men have practised circumcision from the first. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Now let me tell another thing about the Colchians to show how they resemble the Egyptians: they alone work flax in the same fashion as the Egyptians, and the two nations are like one another in their whole manner of living and also in their language: now the linen of Colchis is called by the Greeks Sardonic, whereas that from Egypt is called Egyptian. The pillars which Sesostris king of Egypt set up in the various countries are for the most part no longer to be seen extant; but in Syria Palestine I myself saw them existing with the inscription upon them which I have mentioned and the emblem. Moreover in Ionia there are two figures of this man carved upon rocks, one on the road by which one goes from the land of Ephesos to Phocaia, and the other on the road from Sardis to Smyrna. In each place there is a figure of a man cut in the rock, of four cubits and a span in height, holding in his right hand a spear and in his left a bow and arrows, and the other equipment which he has is similar to this, for it is both Egyptian and Ethiopian: and from the one shoulder to the other across the breast runs an inscription carved in sacred Egyptian characters, saying thus, "This land with my shoulders I won for myself. " But who he is and from whence, he does not declare in these places, though in other places he had declared this. Some of those who have seen these carvings conjecture that the figure is that of Memnon, but herein they are very far from the truth.

In 1984, adventurer Steve Severin built a 54-foot galley, like the one Jason used, and assembled a crew of strong rowers to follow Jason's route through along the Greek Adriatic and the Turkish Black Sea coasts. Researching and building the sail and oar vessel took three years and Severin used the same materials the Greeks used (mainly Aleppo pine) and fastened the timber together with mortise-and-tenon joints instead of nails, as the ancient Greeks did. The 1,500 mile journey took three months. On average 10 of the 16 rowers rowed at one time and when there was no wind they averaged about three miles an hour. They navigated by following the land with their eyes as the Greeks did.⊛

Jason's Mission; Securing the Golden Fleece

Claiming the Golden Fleece was regarded as an impossible task. It hung in a sacred grove guarded by an enormous serpent. If Jason managed to bring it home he could reclaim his rightful place on his father’s throne taken from him by his uncle Pelias. For thousands of years gold dust has been extracted from the rivers draining the Caucasus area by placing sheepskins on the stream bottom to trap particles. The expression the golden fleece is believed to have possibly been derived from this practice.

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “According to the legend, Jason was deprived of his expectation of the throne of Iolkos (a real kingdom situated in the locale of present day Volos) by his uncle, King Pelias, who usurped the throne. Jason was taken from his parents, and was brought up on Mount Pelion, in Thessaly, by a centaur named Cheiron. Meantime his uncle lived in dread of an oracle's prophecy, which said he should fear the 'man with one shoe'. [Source: Michael Wood, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“At the age of 20 Jason set off to return to Iolkos - on his journey losing a sandal in the river while helping Hera, Queen of the Gods, who was in disguise as an old woman. On arriving before King Pelias, Jason revealed who he was and made a claim to the kingdom. The king replied, 'If I am to give you the kingdom, first you must bring me the Fleece of the Golden Ram'. |::| And this was the hero's quest. His task would take him beyond the known world to acquire the fleece of a magical ram that once belonged to Zeus, the king of the gods. Jason's ancestor Phrixus had flown east from Greece to the land of Cochlis (modern day Georgia) on the back of this ram. King Aietes, son of Helios the sun god, had then sacrificed the ram and hung its fleece in a sacred grove guarded by a dragon. An oracle foretold that Aietes would lose his kingdom if he lost the fleece, and it was from Aietes that Jason had to retrieve it. |::|

“Why a fleece? Fleeces are connected with magic in many folk traditions. For the ancient Etruscans a gold coloured fleece was a prophecy of future prosperity for the clan. Recent discoveries about the Hittite Empire in Bronze Age Anatolia show celebrations where fleeces were hung to renew royal power. This can offer insight into Jason's search for the fleece and Aietes' reluctance to relinquish it. The fleece represented kinship and prosperity. |::|

Jason and the Argonauts in Black Sea Area

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “Jason's ship, the Argo, began its journey with a crew of 50 (which swelled to 100, including Hercules, in subsequent retellings of the myth) - known as the 'Argonauts'. The Greek claim that the Argo was the first ship ever built can not be true, but Jason's journey was seen by the ancient Greeks as the first long-distance voyage ever undertaken. [Source: Michael Wood, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Indeed, the voyage can be seen as a metaphor for the opening up of the Black Sea coast. Historically, once the Greeks learned to sail into the Black Sea they embarked on a period of colonisation lasting some 3,000 years - but the time they first arrived in the region is still controversial. |::|

“Lemnos, an island in the north-eastern Aegean was Jason's first stop. This was a place inhabited by women who had murdered their husbands after being cursed by Aphrodite. Next the Argo sailed to Samothrace, where the Argonauts were initiated into the Kabeiroi, a cult of 'great gods' who were not Greek and who offered protection to seafarers. From Samothrace the adventurers passed the city of Troy by night, and entered the Sea of Marmara the next day. |::|

“The Jason tale is a founding myth for many towns along this shore. It is, however, most likely that local accounts of events have arisen out of the story itself, rather than being based on historic facts that themselves became the basis of the myth. |::|

“It is along this stretch of coast that the Argonauts rescue a blind prophet, Phineus, by chasing away the Harpies - the ugly winged females Zeus had sent to torment Phineus. In return Phineus prophesies that Jason will be the first mariner to sail through the 'clashing rocks' that guard the entrance to the Black Sea. The myth arose when Greek sailors were first able to negotiate their way up the powerful currents of the Bosphorus to enter the Black Sea beyond. In time the sea was transformed in Greek eyes from Axeinos Pontus, the 'hostile sea' to Euxeinos Pontus, the 'welcoming sea'. |::|

Jason in Colchis

Jason secures the Golden Fleece

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “The story continues with the Argonauts finally reaching the land of Colchis, and the first part of their quest is achieved. The heroes land and hold council, deciding to walk up to the city of Aia. Along the way they see bodies wrapped in hides and hung in trees, a sight that travellers in Georgia recount right up to the 17th century. [Source: Michael Wood, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Once in Colchis Jason asks King Aietes to return the Golden Fleece. Aietes agrees to do so if Jason can perform a series of superhuman tasks. He has to yoke fire-breathing bulls, plough and sow a field with dragons' teeth, and overcome phantom warriors. In the meantime Aphrodite (the goddess of love) makes Medea, daughter of King Aietes, fall in love with Jason. Medea offers to help Jason with his tasks if he marries her in return. He agrees, and is enabled to complete the tasks. |

“King Aietes organises a banquet, but confides to Medea that he will kill Jason and the Argonauts rather than surrender the Golden Fleece. Medea tells Jason, and helps him retrieve the Fleece. From here the Argonauts flee home, encountering further epic adventures. The ancient storytellers give several versions of the route Jason took back to Greece, reflecting changes in Greek ideas about the geography of the world. |::|

“On the final leg of their journey, the Argonauts are caught in a storm, and after they pray to Apollo an island appears to them. The inhabitants of modern-day Anafi, 'the one which was revealed', and which is said to be the island in question, continue to celebrate their part in the story to this day. They regularly hold a festival inside an ancient temple to Apollo, built on the spot where legend says Jason gave thanks to the god for his rescue. |::|

City of Aia

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “The ancient Greeks speak of Aia as a real city on the River Phasis (the modern River Rhion). Archaeologists have yet to find it, although in 1876 gold treasure was found in this region at an ancient site near the town of Vani, and it was suggested that this might be the city of the Argonaut legend. Heinrich Schlieman, the excavator of Troy and Mycenae, proposed to dig here but was not given permission. |::|

“Then in 1947 excavations revealed that between 600 and 400 B.C. (the time the Jason legend took its final shape) Vani was indeed an important Colchin city. The city was not inhabited during the Heroic Age (when the Jason story is set), but it was the Colchin 'capital' at the time the Greek poets located the myth here. This suggests that some parts of the myth depict the culture of the historical Iron Age rather than the earlier Bronze Age of Jason. |::|

Jason’s Return Home

Michael Wood of the BBC wrote: “On his return to Iolkos Jason discovers that King Pelias has killed his father, and his mother has died of grief. Medea tricks Pelias by offering to rejuvenate him, and then kills him. Jason and Medea go into exile in Corinth, where Jason betrays Medea by marrying the king's daughter. Medea takes revenge by killing her own children by Jason. [Source: Michael Wood, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Pausanias, in his first-century guidebook to Greece, describes a shrine to the murdered children next to a temple to Hera, queen of gods, at Corinth. Centuries later, in the 1930s, a British excavation at Perachora uncovered an eighth-century B.C. temple to Hera, supposedly dedicated by Medea, near an oracle site with pilgrimage offerings left by women devotees over many centuries - perhaps there's a historic basis to the myth?

“In the end, Jason becomes a wanderer once more, and eventually returns to beached hull of the Argo. Here the beam of the ship (which was said to speak and was named Dodona) falls on him and kills him. His story has come full circle - as in all Greek myths, the hero's destiny is in the hands of the gods. |::|

Sacrifice to Rhea: the Phrygian Mother-Goddess

On “A Sacrifice to Rhea, The Phrygian Mother-Goddess, Apollonius Rhodius wrote in “Argonautica,” I, 1078-1150: “After this, fierce tempests arose for twelve days and nights together and kept them there from sailing. But in the next night the rest of the chieftains, overcome by sleep, were resting during the latest period of the night, while Acastus and Mopsus the son of Ampycus kept guard over their deep slumbers. And above the golden head of Aeson's son there hovered a halcyon prophesying with shrill voice the ceasing of the stormy winds; and Mopsus heard and understood the cry of the bird of the shore, fraught with good omen. And some god made it turn aside, and flying aloft it settled upon the stern-ornament of the ship. [Source: translation by R. C. Seaton, in the Loeb Classical Library (New York, 1912), PP. 77-81]

Jason with Golden Fleece

“And the seer touched Jason as he lay wrapped in soft sheepskins and woke him at once, and thus spake: ‘'Son of Aeson, thou must climb to this temple on rugged Dindymum and propitiate the mother (i.e., Rhea) of all the blessed gods on her fair throne, and the stormy blasts shall cease. For such was the voice I heard but now from the halcyon, bird of the sea, which, as it flew above thee in thy slumber, told me all. For by her power the winds and the sea and all the earth below and the snowy seat of Olympus are complete; and to her, when from the mountains she ascends the mighty heaven, Zeus himself, the son of Cronos, gives place. In like manner the rest of the immortal blessed ones reverence the dread goddess.'

“Thus he spake, and his words were welcome to Jason's ear. And he arose from his bed with joy and woke all his comrades hurriedly and told them the prophecy of Mopsus the son of Ampycus. And quickly the younger men drove oxen from their stalls and began to lead them to the mountain's lofty summit. And they loosed the hawsers from the sacred rock and rowed to the Thracian harbour; and the heroes climbed the mountain, leaving a few of their comrades in the ship. And to them, the Macrian heights and all the coast of Thrace opposite appeared to view dose at hand. And there appeared the misty mouth of Bosporus and the Mysian hills; and on the other side the stream of the river Aesepus and the city and Nepian plain of Adrasteia. Now there was a sturdy stump of vine that grew in the forest, a tree exceeding old; this they cut down, to be the sacred image of the mountain goddess; and Argos smoothed it skillfully, and they set it upon that rugged hill beneath a canopy of lofty oaks, which of all trees have their roots deepest. And near it they heaped an altar of small stones and wreathed their brows with oak leaves and paid heed invoking the mother of Dindymum, most venerable, dweller in Phrygia and Titas and Cyllenus, who alone of many are called dispensers of doom and assessors of the Idaean mother-the Idaean Dactyls of Crete, whom once the nymph Anchiale, as she grasped with both hands the land of Oaxus, bare in the Dictaean cave. And with many prayers did Aeson's son beseech the goddess to turn aside the stormy blasts as he poured libations on the blazing sacrifice; and at the same time by command of Orpheus the youths trod a measure dancing in full armour, and dashed with their swords on their shields, so that the ill-omened cry might be lost in the air-the wail which the people were still sending up in grief for their king. Hence from that time forward the Phrygians propitiate Rhea with the wheel and the drum. And the gracious goddess, I ween, inclined her heart to pious sacrifices; and favourable signs appeared. The trees shed abundant fruit, and round their feet the earth of its own accord put forth flowers from the tender grass. And the beasts of the wild wood left their lairs and thickets and came up fawning on them with their tails. And she caused yet another marvel; for hitherto there was no flow of water on Dindymum, but then for them an unceasing stream gushed forth from the thirsty peak just as it was, and the dwellers around in after times called that stream, the spring of Jason. And then they made a feast in honour of the goddess on the Mount of Bears, singing the praises of Rhea most venerable; but at dawn the winds had ceased and they rowed away from the island.”

Talos — The World’s First Evil Robot

Jason when he, the Argonauts featured Talos — a bronze goant and The first “robot” to walk the earth. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Talos was one of a trinity of technological advanced gifts bequeathed by Zeus to his son Minos, the first king of Crete. An anthropomorphic machine, Talos would patrol the coastline of Crete three times a day, keeping watch for pirates. He would hurl boulders at foreign ships and, if he identified a “stranger,” would clutch them to his chest, heat up his bronze torso, and roast his captive alive. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 22, 2019]

Talos proved something of a challenge for Jason when he, the Argonauts, and his wife Medea arrived on the island. In the end it was Medea who came to Jason’s rescue. She used telepathy to confuse the metal giant and disorient him. The giant stumbles around and a rock strikes against the bolt that dams the single “vein” in his ankle. The bolt is dislodged, the giant’s life force drains out of him, and he dies.

Interestingly, ancient tech continues to influence modern invention, especially in the military arena. In 1948 a ramjet missile was named Talos, after the Cretan robot. Then, in 2013, Talos experienced something of a rebirth. The US Special Operations Command and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency started a project to create a special ops robotic exoskeleton (yes, like Iron Man). The purpose of the suit, Mayor writes, is to provide superhuman strength, heightened sensory awareness, and ballistic protection. They self-consciously named it the Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit (TALOS). The project has not been completed.

Medea — the Ultimate Bad Mother

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Arguably the poster girl for bad mothers is Medea, the antihero of the Greek playwright Euripides’ eponymous play. According to Greek mythology, Medea was the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. She features in the story of Jason and the Gold Fleece in which she plays a central role in Jason’s success. In Apollonius of Rhodes’s Argonautica, Medea promises to help Jason reclaim his inheritance and throne if he agrees to marry her afterwards. It is largely thanks to Medea that Jason is able to complete the otherwise-impossible tasks that her father sets for him. Subsequently, Medea and Jason marry and (if this was a different kind of story) should have lived happily ever after. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 12, 2019]

According to all the sources Jason casts aside Medea for Glauce, the daughter of the King of Corinth. Euripides, however, gives us a drama in which, in a jealous love-filled rage, Medea kills not only Glauce (via poisoned dress) but all of her and Jason’s children. In the play it’s not an easy decision for her: it is simply the only way for her to seek vengeance on the man who had betrayed her. Like so many other ‘bad mothers’ of history she is depicted as having traditional ‘masculine’ personality traits like intelligence. Emma Griffiths, a classicist at the University of Manchester, argues that Medea’s categorization as a witch and powerful intellectual force puts her at odds with ancient conventions about the role of women. And it’s worth noting that there are plenty of other ancient stories about Medea that make her seem more like a lovestruck young girl or talented healer, than a crazed killer.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024