Home | Category: Gods and Mythology / Literature and Drama

THESEUS

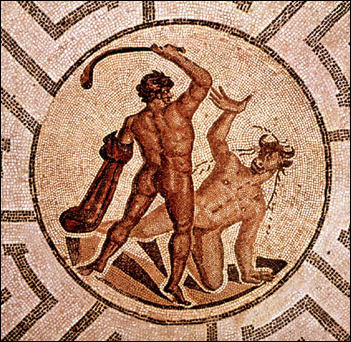

Theseus-Minotaur mosaic Theseus was another great Greek hero. The son of the King of Athens, he was raised in a distant land and didn’t arrive in Athens until he was a young man strong enough to lift a stone under which his father placed a sword and a pair of sandals. After becoming King of Athens he fought with Centaurs and battled Amazons and was one of Jason's Argonauts.

But for the most part Theseus was kind a jerk. The only reason he escaped the Minotaur was because he had help from Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos, and then totally screwed her. Debra Kelly wrote in Listverse Ariadne had a magical ball of golden thread that allowed Theseus to find his way out again.After the Minotaur was dead, Theseus left Crete with the princess who had saved his life—and then abandoned her on the island of Naxos when she fell asleep. According to some stories, Ariadne had a happy ending when she married the god Dionysus and was granted immortality—or she was killed by Artemis. [Source Debra Kelly, Listverse, December 17, 2013]

Either way, Theseus is still a jerk, and had already had some children with a few other women.And let’s not forget that Theseus forgot to hoist a red sail on his ship upon his return from Crete, a signal to his father that he was safe. His father, not seeing the signal, threw himself from the cliff in despairing suicide. Theseus is also given credit for founding Athens. According to Plutarch, Theseus decided that there was no better way to populate his young city than by raping the women, earning him the eternal hatred of his newfound kin.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Theseus and the Minotaur (Myths and Legends) by Graeme Davis (Author), José Daniel Cabrera Peña (Illustrator) (2014) Amazon.com;

“Perseus, Theseus: Adapted from "What The Ancient Greeks And Romans Told About Their Gods And Heroes" by Nikolay A. Kun Amazon.com;

“Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth” by J. A. MacGillivray (2000) Amazon.com;

“Knossos - A Complete Guide to the Palace of Minos” by Anna Michailidou (2004) Amazon.com;

“Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality” by Andrew Shapland (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Palace of Minos at Knossos” by Chris Scarre and Rebecca Stefoff (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Author Amazon.com;

“D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths” by Ingri and Edgar Parin d'Aulaire (1962) Amazon.com;

“The Complete World of Greek Mythology” by Richard Buxton (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Myths” by Robert Graves (1955) Amazon.com;

“Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes” by Edith Hamilton (1942) Amazon.com;

“Hellenic Polytheism: Household Worship” by Christos Pandion Panopoulos (2014) Amazon.com;

“Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Alexandra Sofroniew (2015) Amazon.com;

“When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East” by Carolina López-Ruiz (2010) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of the Gods” by Jacquetta Hawkes (1968) Amazom.com

“The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology” by Martin P. Nilsson (1932) Amazon.com;

“Mythos: The Greek Myths Reimagined” by Stephen Fry (2017) Amazon.com;

“Heroes” by Stephen Fry (2019) Amazon.com;

Theseus, the Minotaur and the Labyrinth

The story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth is set in Crete, presumably during the Minoan era. According to legend, King Minos was a wise leader and a just lawgiver who ruled Crete from Knossos and lived in a magnificent palace. One day the sea-god Poseidon gave him a magnificent white bull that was intended to be sacrificed in the sea god's honor. Minos greedily kept the bull instead and Poseidon got even with the king by casting a spell on his wife, which made her want to make love with the bull, which she did, producing the Minotaur. Daedalus, the Athenian architect who later tried to fly to Sicily with wings made of wax, built the Labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur.

After King Minos's son was killed in Athens the king captured Athens and secured an annual tribute of seven youths and seven virgins to be eaten by the Minotaur. One of youths offered to the Minotaur — Theseus — fell in love with King Minos's daughter. Daedalus gave Theses a ball of string so that he could find his way out of the labyrinth of he managed to kill the Minotaur. After slaying the Minotaur Theseus fled Crete with king’s daughter but as was true with heros in other Greek myths, such as Jason from the Argonauts, Theseus abandoned the girl after winning his freedom.

The Minoans believed that King Minos was the son of Europa, the daughter of King Sidon, and Zeus transformed into a bull. The association of the Minotaur myth with Knossos can be traced to Sir Arthur Evans, the British adventurer, who excavated Knossos in the 1890s. He reportedly was struck by the size of Knossos and its large number of rooms that he figured it must be the source of the labyrinth myth. Some have said he defied one of the cornerstones of archaeology by forcing evidence to fit his model rather than letting evidence speak for itself. Evans is also the source of some other dubious claims about Minoa.

See Life of Theseus by Plutarch (c.46-c.120 CE) at MIT Classics classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/theseus

Was Theseus a Real Person?

Theseus in a Pompeii fresco

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In the ancient Greek world, myth functioned as a method of both recording history and providing precedent for political programs. While today the word "myth" is almost synonymous with "fiction," in antiquity, myth was an alternate form of reality. Thus, the rise of Theseus as the national hero of Athens, evident in the evolution of his iconography in Athenian art, was a result of a number of historical and political developments that occurred during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. [Source: Andrew Greene, Intern, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Myth surrounding Theseus suggests that he lived during the Late Bronze Age, probably a generation before the Homeric heroes of the Trojan War. The earliest references to the hero come from the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Homeric epics of the early eighth century B.C. Theseus's most significant achievement was the Synoikismos, the unification of the twelve demes, or local settlements of Attica, into the political and economic entity that became Athens. \^/

“There are certain aspects of the myth of Theseus that were clearly modeled on the more prominent hero Herakles during the early sixth century B.C. Theseus's encounter with the brigands parallels Herakles's six deeds in the northern Peloponnese. Theseus's capture of the Marathonian Bull mirrors Herakles's struggle with the Cretan Bull. There also seems to be some conflation of the two since they both partook in an Amazonomachy and a Centauromachy. Both heroes additionally have links to Athena and similarly complex parentage with mortal mothers and divine fathers. \^/

“However, while Herakles's life appears to be a string of continuous heroic deeds, Theseus's life represents that of a real person, one involving change and maturation. Theseus became king and therefore part of the historical lineage of Athens, whereas Herakles remained free from any geographical ties, probably the reason that he was able to become the Pan-Hellenic hero. Ultimately, as indicated by the development of heroic iconography in Athens, Herakles was superseded by Theseus because he provided a much more complex and local hero for Athens. \^/

Theseus’s Life

Theseus was the son of Athira, daughter of Pittheus, king of Troezen.. His father was either Aegeus, king of Athens; or Poseidon. There are several stories regarding his birth. According to one Poseidon slept with Aithra on the same night that King Aegeus of Athens slept with her (in a temple of Poseidon on an island off the shore of Troezen) and he was brought up at Troezen at the court of his grandfather. In another since he was the son of Aithra, daughter of King Pittheus of Troezen (a son of Pelops, and thus a brother of Atreus and Thyestes) he was therefore first-cousin of Agamemnon, Menelaus, Thyestes, Eurystheus, and Alcmene. [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Theseus and an Amazon

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Theseus's life can be divided into two distinct periods, as a youth and as king of Athens. Aegeus, king of Athens, and the sea god Poseidon. Both slept with Theseus's mother, Aithra, on the same night, supplying Theseus with both divine and royal lineage. Theseus was born in Aithra's home city of Troezen, located in the Peloponnese, but as an adolescent he traveled around the Saronic Gulf via Epidauros, the Isthmus of Corinth, Krommyon, the Megarian Cliffs, and Eleusis before finally reaching Athens. Along the way he encountered and dispatched six legendary brigands notorious for attacking travelers. [Source: Andrew Greene, Intern, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Upon arriving in Athens, Theseus was recognized by his stepmother, Medea, who considered him a threat to her power. Medea attempted to dispatch Theseus by poisoning him, conspiring to ambush him with the Pallantidae Giants, and by sending him to face the Marathonian Bull . \^/

“There is but a sketchy picture of Theseus's deeds in later life, gleaned from brief literary references of the early Archaic period, mostly from fragmentary works by lyric poets. Theseus embarked on a number of expeditions with his close friend Peirithoos, the king of the Lapith tribe from Thessaly in northern Greece. He also undertook an expedition against the Amazons, in some versions with Herakles, and kidnapped their queen Antiope, whom he subsequently married. Enraged by this, the Amazons laid siege to Athens, an event that became popular in later artistic representations.” Theseus died by leaping (or being pushed) into the sea from the Island of Skyros when he was the guest of its king Lykomedes. Achilles hid on the island of Skyros before being drafted for the Trojan War!

Theseus Legends

During Theseus’s journey to Athens to claim his inheritance from his father Aegeus,: 1) he cleaned up the coast road from Troezen through Corinth, Megara, Eleusis and Athens of bandits and robbers: 2) enocuntered Sciron, Procrustes, Corynetes (at Epidauros), Sinis and the Crommyonian sow (compare this to the Erymanthian boar of the Heracles' story) and wrestled with and killed King Kerkyon of Eleusis Theseus formed a friendship with Perithoos (King of Thessalian Lapithai), attending his wedding banquet and taking part in the Battle of the Lapiths with and Centaurs. He visited the Underworld: in an attempt to rescue Persephone but got trapped there when he sat down on stone chairs ('Thrones of Memory') and was unable to get up. He was eventually freed by Heracles. Theseus is also featured in Euripides' play “Hippolytus.” [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Theseus and the Centaur

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “One of the Troezenian legends about Theseus is the following. When Heracles visited Pittheus at Troezen, he laid aside his lion's skin to eat his dinner, and there came in to see him some Troezenian children with Theseus, then about seven years of age. The story goes that when they saw the skin the other children ran away, but Theseus slipped out not much afraid, seized an axe from the servants and straightway attacked the skin in earnest, thinking it to be a lion. This is the first Troezenian legend about Theseus. The next is that Aegeus placed boots and a sword under a rock as tokens for the child, and then sailed away to Athens; Theseus, when sixteen years old, pushed the rock away and departed, taking what Aegeus had deposited. There is a representation of this legend on the Acropolis, everything in bronze except the rock. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“Another deed of Theseus they have represented in an offering, and the story about it is as follows: The land of the Cretans and especially that by the river Tethris was ravaged by a bull. It would seem that in the days of old the beasts were much more formidable to men, for example the Nemean lion, the lion of Parnassus, the serpents in many parts of Greece, and the boars of Calydon, Eryrmanthus and Crommyon in the land of Corinth, so that it was said that some were sent up by the earth, that others were sacred to the gods, while others had been let loose to punish mankind. And so the Cretans say that this bull was sent by Poseidon to their land because, although Minos was lord of the Greek Sea, he did not worship Poseidon more than any other god. They say that this bull crossed from Crete to the Peloponnesus, and came to be one of what are called the Twelve Labours of Heracles. When he was let loose on the Argive plain he fled through the isthmus of Corinth, into the land of Attica as far as the Attic parish of Marathon, killing all he met, including Androgeos, son of Minos.

“Minos sailed against Athens with a fleet, not believing that the Athenians were innocent of the death of Androgeos, and sorely harassed them until it was agreed that he should take seven maidens and seven boys for the Minotaur that was said to dwell in the Labyrinth at Cnossus. But the bull at Marathon Theseus is said to have driven afterwards to the Acropolis and to have sacrificed to the goddess; the offering commemorating this deed was dedicated by the parish of Marathon.”

On Theseus and the Bull of Marathon, Plutarch wrote: “Theseus, longing to be in action, and desirous also to make himself popular, left Athens to fight with the bull of Marathon, which did no small mischief to the inhabitants of Tetrapolis. And having overcome it, he brought it alive in triumph through the city, and afterwards sacrificed it to the Delphinian Apollo. The story of Hecale, also, of her receiving and entertaining Theseus in this expedition, seems to be not altogether void of truth; for the townships round about, meeting upon a certain day, used to offer a sacrifice which they called Hecalesia, to Jupiter Hecaleius, and to pay honour to Hecale, whom, by a diminutive name, they called Hecalene, because she, while entertaining Theseus, who was quite a youth, addressed him, as old people do, with similar endearing diminutives; and having made a vow to Jupiter for him as he was going to the fight, that, if he returned in safety, she would offer sacrifices in thanks of it, and dying before he came back, she had these honours given her by way of return for her hospitality, by the command of Theseus, as Philochorus tells us.” [Source: Plutarch, “Life of Theseus,” A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden]

Theseus and the Minotaur

Minotaur labyrinth

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ Athens was forced to pay an annual tribute of seven maidens and seven youths to King Minos of Crete to feed the Minotaur, half man, half bull, that inhabited the labyrinthine palace of Minos at Knossos. Theseus, determined to end Minoan dominance, volunteered to be one of the sacrificial youths. On Crete, Theseus seduced Minos's daughter, Ariadne, who conspired to help him kill the Minotaur and escape by giving him a ball of yarn to unroll as he moved throughout the labyrinth. Theseus managed to flee Crete with Ariadne, but then abandoned her on the island of Naxos.” where she was taken up by Dionysus, “during the voyage back to Athens. King Aegeus had told Theseus that upon returning to Athens, he was to fly a white sail if he had triumphed over the Minotaur, and to instruct the crew to raise a black sail if he had been killed. Theseus, forgetting his father's direction, flew a black sail as he returned. Aegeus, in his grief, threw himself from the cliff at Cape Sounion into the Aegean, making Theseus the new king of Athens and giving the sea its name.” [Source: Andrew Greene, Intern, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

On the Minotaur story, Plutarch wrote: “Not long after arrived the third time from Crete the collectors of the tribute which the Athenians paid them upon the following occasion. Androgeus having been treacherously murdered in the confines of Attica, not only Minos, his father, put the Athenians to extreme distress by a perpetual war, but the gods also laid waste their country; both famine and pestilence lay heavy upon them, and even their rivers were dried up. Being told by the oracle that, if they appeased and reconciled Minos, the anger of the gods would cease and they should enjoy rest from the miseries they laboured under, they sent heralds, and with much supplication were at last reconciled, entering into an agreement to send to Crete every nine years a tribute of seven young men and as many virgins, as most writers agree in stating; and the most poetical story adds, that the Minotaur destroyed them, or that, wandering in the labyrinth, and finding no possible means of getting out, they miserably ended their lives there; and that this Minotaur was (as Euripides hath it): “"A mingled form where two strange shapes combined, /And different natures, bull and man, were joined." [Source: Plutarch, “Life of Theseus,” A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden]

“But Philochorus says that the Cretans will by no means allow the truth of this, but say that the labyrinth was only an ordinary prison, having no other bad quality but that it secured the prisoners from escaping, and that Minos, having instituted games in honour of Androgeus, gave, as a reward to the victors, these youths, who in the meantime were kept in the labyrinth; and that the first that overcame in those games was one of the greatest power and command among them, named Taurus, a man of no merciful or gentle disposition, who treated the Athenians that were made his prize in a proud and cruel manner. Also Aristotle himself, in the account that he gives of the form of government of the Bottiaeans, is manifestly of opinion that the youths were not slain by Minos, but spent the remainder of their days in slavery in Crete; that the Cretans, in former times, to acquit themselves of an ancient vow which they had made, were used to send an offering of the first-fruits of their men to Delphi, and that some descendants of these Athenian slaves were mingled with them and sent amongst them, and, unable to get their living there, removed from thence, first into Italy, and settled about Japygia; from thence again, that they removed to Thrace, and were named Bottiaeans; and that this is the reason why, in a certain sacrifice, the Bottiaean girls sing a hymn beginning Let us go to Athens. This may show us how dangerous it is to incur the hostility of a city that is mistress of eloquence and song. For Minos was always ill spoken of, and represented ever as a very wicked man, in the Athenian theatres; neither did Hesiod avail him by calling him "the most royal Minos," nor Homer, who styles him "Jupiter's familiar friend;" the tragedians got the better, and from the vantage ground of the stage showered down obloquy upon him, as a man of cruelty and violence; whereas, in fact, he appears to have been a king and a law-giver, and Rhadamanthus, a judge under him, administering the statutes that he ordained.

Theseus killing the Minotaur

“Now, when the time of the third tribute was come, and the fathers who had any young men for their sons were to proceed by lot to the choice of those that were to be sent, there arose fresh discontents and accusations against Aegeus among the people, who were full of grief and indignation that he who was the cause of all their miseries was the only person exempt from the punishment; adopting and settling his kingdom upon a bastard and foreign son, he took no thought, they said, of their destitution and loss, not of bastards, but lawful children. These things sensibly affected Theseus, who, thinking it but just not to disregard, but rather partake of, the sufferings of his fellow-citizens, offered himself for one without any lot. All else were struck with admiration for the nobleness and with love for the goodness of the act; and Aegeus, after prayers and entreaties, finding him inflexible and not to be persuaded, proceeded to the choosing of the rest by lot. Hellanicus, however, tells us that the Athenians did not send the young men and virgins by lot, but that Minos himself used to come and make his own choice, and pitched upon Theseus before all others; according to the conditions agreed upon between them, namely, that the Athenians should furnish them with a ship and that the young men that were to sail with him should carry no weapons of war; but that if the Minotaur was destroyed, the tribute should cease.

“On the two former occasions of the payment of the tribute, entertaining no hopes of safety or return, they sent out the ship with a black sail, as to unavoidable destruction; but now, Theseus encouraging his father, and speaking greatly of himself, as confident that he should kill the Minotaur, he gave the pilot another sail, which was white, commanding him, as he returned, if Theseus were safe, to make use of that; but if not, to sail with the black one, and to hang out that sign of his misfortune. Simonides says that the sail which Aegeus delivered to the pilot was not white, but "Scarlet, in the juicy bloom Of the living oak-tree steeped," and that this was to be the sign of their escape.”

Images of Theseus

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The earliest extant representation of Theseus in art appears on the François Vase located in Florence, dated to about 570 B.C. This famous black-figure krater shows Theseus during the Cretan episode, and is one of a small number of representations of Theseus dated before 540 B.C. Between 540 and 525 B.C., there was a large increase in the production of images of Theseus, though they were limited almost entirely to painted pottery and mainly showed Theseus as heroic slayer of the Minotaur. [Source: Andrew Greene, Intern, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Around 525 B.C., the iconography of Theseus became more diverse and focused on the cycle of deeds involving the brigands and the abduction of Antiope. Between 490 and 480 B.C., interest centered on scenes of the Amazonomachy and less prominent myths such as Theseus's visit to Poseidon's palace. The episode is treated in a work by the lyric poet Bacchylides. Between 450 and 430 B.C., there was a decline in representations of the hero on vases; however, representations in other media increase. In the mid-fifth century B.C., youthful deeds of Theseus were placed in the metopes of the Parthenon and the Hephasteion, the temple overlooking the Agora of Athens. Additionally, the shield of Athena Parthenos, the monumental chryselephantine cult statue in the interior of the Parthenon, featured an Amazonomachy that included Theseus. \^/

Theseus and Athens

Temple of Theseus in Athens

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The rise in prominence of Theseus in Athenian consciousness shows an obvious correlation with historical events and particular political agendas. In the early to mid-sixth century B.C., the Athenian ruler Solon (ca. 638–558 B.C.) made a first attempt at introducing democracy. It is worth noting that Athenian democracy was not equivalent to the modern notion; rather, it widened political involvement to a larger swath of the male Athenian population. Nonetheless, the beginnings of this sort of government could easily draw on the Synoikismos as a precedent, giving Solon cause to elevate the importance of Theseus. Additionally, there were a large number of correspondences between myth and historical events of this period. As king, Theseus captured the city of Eleusis from Megara and placed the boundary stone at the Isthmus of Corinth, a midpoint between Athens and its enemy. Domestically, Theseus opened Athens to foreigners and established the Panathenaia, the most important religious festival of the city. Historically, Solon also opened the city to outsiders and heightened the importance of the Panathenaia around 566 B.C. [Source: Andrew Greene, Intern, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“When the tyrant Peisistratos seized power in 546 B.C., as Aristotle noted, there already existed a shrine dedicated to Theseus, but the exponential increase in artistic representations during Peisistratos's reign through 527 B.C. displayed the growing importance of the hero to political agenda. Peisistratos took Theseus to be not only the national hero, but his own personal hero, and used the Cretan adventures to justify his links to the island sanctuary of Delos and his own reorganization of the festival of Apollo there. It was during this period that Theseus's relevance as national hero started to overwhelm Herakles's importance as Pan-Hellenic hero, further strengthening Athenian civic pride. \^/

“Under Kleisthenes, the polis was reorganized into an even more inclusive democracy, by dividing the city into tribes, trittyes, and demes, a structure that may have been meant to reflect the organization of the Synoikismos. Kleisthenes also took a further step to outwardly claim Theseus as the Athenian hero by placing him in the metopes of the Athenian treasury at Delphi, where he could be seen by Greeks from every polis in the Aegean. \^/

“The oligarch Kimon (ca. 510–450 B.C.) can be considered the ultimate patron of Theseus during the early to mid-fifth century B.C. After the first Persian invasion (ca. 490 B.C.), Theseus came to symbolize the victorious and powerful city itself. At this time, the Amazonomachy became a key piece of iconography as the Amazons came to represent the Persians as eastern invaders. In 476 B.C., Kimon returned Theseus's bones to Athens and built a shrine around them which he had decorated with the Amazonomachy, the Centauromachy, and the Cretan adventures, all painted by either Mikon or Polygnotos, two of the most important painters of antiquity. This act represented the final solidification of Theseus as national hero.” |^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024