Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

DRAMA AND THEATER IN ANCIENT ROME

Theater performance

In the early days of Roman theater, Greek tragedies and comedies were very popular. Roman theater included farce and pantomime. Nudity and live acts of violence drew large audiences. As Roman theaters grew larger and less intimate and the spoken word became more difficult to hear, dialogue was replaced with songs, which transformed soloists into major stars.

The art of pantomime — the solo performance of a dramatic narrative in which a dancer or performer portray all characters — was developed by dancers for performances in the great Roman arenas. The performers used movements and gestures that had a clear meaning to the spectators. Pantomimists became famous for their ability to relate entire stories with gestures and postures. They sometimes wore masks and avish costumes and jewelry.

Roman theater was mainly a copy of Greek drama and not a very good one that. Not very Roman plays are produced today. Actors were regarded as just one rung above prostitutes. Romans appear to have been more interested in gladiator battles, chariot races and large spectacles and less interested in drama and Olympic-style sports as was the case with ancient Greeks. The Olympics, however, continued through the Roman era as a pagan festival, with Nero among those that attended, until they were shut down by the Christian Roman emperor Theodosius I, who ordered the closure of all pagan events in 393.

In Rome as well as in Athens the drama was connected with religious festivals and the funerals of the great, but it encountered much opposition from the more old-fashioned moralists and was never so popular as were grosser amusements. The actors were frequently slaves, though citizens engaged in this profession in increasing numbers under the late Republic and the Empire, but their occupation deprived them of certain civil rights and affected their social standing; while at Athens parts in both tragedies and comedies were taken by citizens, who lost nothing in public estimation by so doing. This in itself shows the marked difference in the Greek and Roman attitudes. Roman tragedy was closely modeled upon the Athenian, and the plays of Menander and his contemporaries, translated and adapted by Plautus and Terence, became Roman comedy, from which the classic comedy of modern Europe is derived. More popular, however, were the farces and pantomimes of various kinds, in which the native influence was strong, the dialogue and gestures being largely extemporaneous, thus affording an opportunity to a clever actor for displaying all his skill. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

RELATED ARTICLES:

THEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

JUVENAL'S SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN LITERATURE, BOOKS AND THE BOOK MARKET europe.factsanddetails.com

CLASSICS OF ROMAN LITERATURE europe.factsanddetails.com

SATYRICON europe.factsanddetails.com

AENEID: VIRGIL, STORY, HISTORY, THEMES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Roman Drama: All the Extant Comedies of Plautus and Terence, and the Tragedies of Seneca, in a Variety of Translations” by George Duckworth (1942) Amazon.com;

“Roman Comedy: Five Plays by Plautus and Terence: Menaechmi, Rudens and Truculentus” translated by David Christenson (2010) Amazon.com;

“Terence and the Language of Roman Comedy” by Evangelos Karakasis (2005)

Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre” by Marianne McDonald and Michael Walton (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Greek and Roman Stage” by David Taylor (1999) Amazon.com;

“Theater and Spectacle in the Art of the Roman Empire” by Katherine M. D. Dunbabin (2016) Amazon.com;

“Living Theatre in the Ancient Roman House: Theatricalism in the Domestic Sphere”

by Richard C. Beacham, Hugh Denard Amazon.com;

“The Roman Amphitheatre: From its Origins to the Colosseum” by Katherine E. Welch (2007) Amazon.com

“Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study” (Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology) by Frank Sear Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” by Frank Sear (1998) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Latin Literature: An Anthology” (Penguin Classics) by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature” by J. C. Mckeown Peter E. Knox Amazon.com;

“Roman Literary Culture, second edition: From Plautus to Macrobius” by Elaine Fantham | (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cicero: Selected Works” by Marcus Tullius Cicero and Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“The Golden Ass” (Oxford World's Classics) by Apuleius, translated by P. G. Walsh Amazon.com

“Rome's Cultural Revolution” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (2008) Amazon.com

“Augustan Culture” by Karl Galinsky (1996) Amazon.com

Spectacles and Theater Entertainment in the Roman World

actor playing the slave Massimo

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Spectacle was an integral part of life in the Roman world. Some forms of spectacle—triumphal processions, aristocratic funerals, and public banquets, for example—took as their backdrop the city itself. Others were held in purpose-built spectator buildings: theaters for plays and other scenic entertainment, amphitheaters for gladiatorial combats and wild beast shows, stadia for athletic competitions, and circuses for chariot races. As a whole, this pervasive culture of spectacle served both as a vehicle for self-advertisement by the sociopolitical elite and as a means of reinforcing the shared values and institutions of the entire community. [Source: Laura S. Klar, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The principal occasions for dramatic spectacles in the Roman world were yearly religious festivals, or ludi, organized by elected magistrates and funded from the state treasury. Temple dedications, military triumphs, and aristocratic funerals also provided opportunities for scenic performances. Until 55 B.C., there was no permanent theater in the city of Rome, and plays were staged in temporary, wooden structures, intended to stand for a few weeks at most. The ancient sources concur that the delay in constructing a permanent theater was due to active senatorial opposition, although the possible reasons for this resistance (concern for Roman morality, fear of popular sedition, competition among the elite) remain a subject of debate. Literary accounts of temporary theaters indicate that they could be quite elaborate. The best documented is a theater erected by the magistrate M. Aemilius Scaurus in 58 B.C., which Pliny reports to have had a stage-building comprised of three stories of columns and ornamented with 3,000 bronze statues. \^/

Of other games that were sometimes given in the amphitheaters something has been said in connection with the circus. The most important were the venationes, hunts of wild beasts. These were sometimes killed by men trained to hunt them, sometimes made to kill one another. As the amphitheater was primarily intended for the butchery of men, the venationes given in it gradually became fights of men against beasts. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The victims were condemned criminals, some of them guilty of crimes that deserved death, some of them sentenced on trumped-up charges, some of them (among these were women and children) condemned “to the lions” for political or religious convictions. Sometimes they were supplied with weapons; sometimes they were exposed unarmed, even fettered or bound to stakes; sometimes the ingenuity of their executioners found additional torments for them by making them play the parts of the sufferers in the tragedies of mythology. The arena could be adapted, too, for the maneuvering of boats, when it had been flooded with water. Naval battles (naumachiae) were often fought, as desperate and as bloody as some of those that have given a new turn to the history of the world. The very earliest exhibitions of this sort were given in artificial lakes, also called naumachiae. The first of these was dug by Caesar, for a single exhibition, in 46 B.C. Augustus had a permanent basin constructed in 2 B.C., measuring 1800 by 1200 feet, and four others at least were built by later emperors.” |+|

Types of Ancient Roman Dramatic Performances

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The earliest Latin plays to have survived intact are the comedies of Plautus (active ca. 205-184 B.C.), which were principally adaptations of Greek New Comedy. Latin tragedy also flourished during the second century B.C. While some examples of the genre treated stories from Greek myth, others were concerned with famous episodes from Roman history. After the second century B.C., the composition of both tragedy and comedy declined precipitously at Rome. During the imperial period, the most popular forms of theatrical entertainment were mime (ribald comic productions with sensational plots and sexual innuendo) and pantomime (performances by solo dancers with choral accompaniment, usually recreating tragic myths). [Source: Laura S. Klar, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006, metmuseum.org \^/]

The history of the development of the drama at Rome belongs, of course, to the history of Latin literature. In classical times dramatic performances consisted of comedies (comoediae), tragedies (tragoediae), farces (mimi), and pantomimes (pantomimi). The farces and pantomimes were used chiefly as interludes and after-pieces, though with the common people they were the most popular of all and outlived the others. Tragedy never had any real hold at Rome, and only the liveliest comedies gained favor on the stage. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

We have 27 Roman comedies, more or less complete, all adaptations from Greek New Comedy by Plautus and Terence. They all depict Greek life, and represented in Greek costumes (fabulae palliatae). They were a good deal more like our comic operas than our comedies; large parts were recited to the accompaniment of music and other parts were sung while the actors danced. Since Roman theaters were not provided with any means of lighting, the plays were always presented in the daytime. In the early period they were given after the noon meal, but by Plautus’s time they had come to be given in the morning. The average comedy must have required about two hours for its performance, if we make allowances for the occasional music between the scenes. |+|

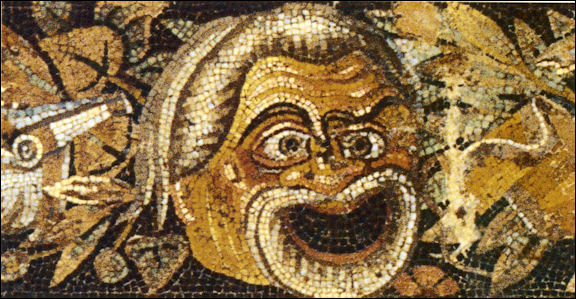

Pompeii Casa del Fauno Mask mosaic

“The play, as well as the other sports, was under the supervision of the state officials in charge of the games at which it was given. They contracted for the production of the play with some recognized manager (dominus gregis), who was usually an actor of acknowledged ability and had associated with him a troupe (grex) of others inferior only to himself. The actors were all slaves, and men took the parts of women. There was no fixed limit to the number of actors, but motives of economy would lead the dominus to produce each play with the smallest number possible, and two or even more parts were often assigned to one actor. The characters in the comedies mentioned above, the fabulae palliatae, wore the ordinary Greek dress of daily life, and the costumes were, therefore, not expensive. The only make-up required in the days of Plautus and Terence was paint for the face, especially for the actors who took women’s parts, and wigs that were used conventionally to represent different characters, gray for old men, black for young men, red for slaves, etc. These and the few properties (ornamenta) necessary were furnished by the dominus. It seems to have been customary also for him to feast the actors at his expense if their efforts to entertain were unusually successful. |+|

Drama in the Roman Empire produced outside of Rome often had local characteristics. According to Archaeology magazine: Four miniature terracotta masks found in the Roman city of Jerash in Jordan shed light on its theater district in the second century A.D. Excavators from the University of Jordan unearthed the masks in a doorway of a structure. The four-inch-tall artifacts depict a bearded Hercules, two horned and goateed faces — likely satyrs — and a curly-haired man who researchers believe is a slave. Such masks were common offerings to Dionysus, the god of theater, and were collected as souvenirs. The masks, whose designs are unique to this location, were probably produced locally. They may have hung on the wall of the structure in whose doorway they were found, which United Arab Emirates University archaeologist Saad Twaissi believes could be a temple dedicated to Dionysus, based on its architectural decorations and proximity to Jerash’s northern theater. The finds challenge previous assumptions that this area was used for industry or dumping refuse and was marginal to Jerash’s center. “Now we can understand the plan of the city better and the relationship between its northern and southern halves,” says Twaissi. [Source: Elizabeth Hewitt, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2023]

Early Drama in Ancient Rome

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “According to the ancient historian Livy, the earliest theatrical activity at Rome took the form of dances with musical accompaniment, introduced to the city by the Etruscans in 364 B.C. The literary record also indicates that Atellanae, a form of native Italic farce (much like the phlyakes of southern Italy), were performed at Rome by a relatively early date. In 240 B.C., full-length, scripted plays were introduced to Rome by the playwright Livius Andronicus, a native of the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy. [Source: Laura S. Klar, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006, metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “According to the ancient historian Livy, the earliest theatrical activity at Rome took the form of dances with musical accompaniment, introduced to the city by the Etruscans in 364 B.C. The literary record also indicates that Atellanae, a form of native Italic farce (much like the phlyakes of southern Italy), were performed at Rome by a relatively early date. In 240 B.C., full-length, scripted plays were introduced to Rome by the playwright Livius Andronicus, a native of the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy. [Source: Laura S. Klar, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006, metmuseum.org \^/]

According to Encyclopedia.com: Livy, writing of the years 364–363 B.C., related that there was plague in Rome. Since neither human remedies nor prayers to the gods abated the plague, the Romans introduced musical shows in the hopes of entertaining them. Etruscan dancers were brought in who danced to a piper's tune. Rome already had a comic tradition; at the harvest home festival or other occasions such as weddings "Fescennine songs" were sung: rough abusive verses chanted antiphonally in improvised repartee. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

On occasion they were composed in the native Latin meter known as "Saturnian"; the Saturnian line consisted of a group of seven syllables, followed by a group of six syllables with a break between them. No one thought crude jokes to be incompatible with solemn ceremonies; even a victorious general celebrating a triumph might hear his soldiers chant Fescennine verses as his procession made its way through the streets of Rome to the temple of Jupiter. One example chanted by Julius Caesar's soldiers chanted about their revered leader as he proceeded through the streets is translated as "City dwellers, lock up your wives / we're bringing in the bald lecher."

Pompeii mosaic actors

Livy reports that the young Romans who saw the Etruscan dancers in the plague year began to imitate them and add improvised, bawdy repartee like Fescennine verses known as satura, or "medleys." There was much suggestive joking and mockery, but no plot worth mention. Fescennine verses were not the only influence, however. The Samnites in Campania between Rome and Naples, who spoke an Italic dialect called Oscan and hence are often known as Oscans, had a taste for slapstick farce with stock characters. When these were introduced into Rome they were called Atellanae after a town in Campania called Atella with which the Romans connected them. Like Punch and Judy shows, the characters were fixed by tradition. There was a clown named Maccus, a simple fellow named Pappus, a fat boy named Bucco, and the hunch-back Dossenus. With their buffoonery and their exaggerated masks, they enjoyed a mass appeal that Latin adaptations of Greek plays never had.

Greek Influence of Roman Drama

According to Encyclopedia.com: The actual staging of dramatic productions in Rome of the sort popular in Greece began with Livius Andronicus, whose translation of Homer's Odyssey into Latin marks the beginning of Latin literature. He began to produce plays with plots. He produced a play translated from the Greek at the Roman Harvest Festival called the Ludi Romani in 240 B.C. which was a milestone in Roman theater for it seems to have been the first time a play was staged in Rome. He wrote more tragedy than comedy, and though he was no great literary figure, he was a pioneer as Rome's first playwright. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Naevius, who came after him, was more at home with comedy than tragedy — not that he wrote original plays, for all his comedies were taken from the Greek New Comedy. He did invent a new type of play which was not borrowed from Greece: the historical drama, or, in Latin, the fabula praetexta. The name came from the toga with a purple border called the toga praetexta worn by Roman magistrates, because the dramas dealt with figures of the Roman past.

After Naevius, historical drama had a very modest success. Some plays dealt with the early history of Rome — Ennius wrote a Rape of the Sabine Women — and others with the victories of generals who were still alive or only recently dead. Ennius had a nephew, Pacuvius, born in 220 B.C., who arrived in Rome as a young man and made a name for himself both as a poet and a painter. His forte was tragedy on Greek subjects — fabulae cothurnatae, so-called from the special elevated boots called cothurni which tragic actors wore. We know the titles of thirty tragedies that he wrote, but none survive. The same fate awaited the plays of a more significant tragedian, Accius, who overlapped Pacuvius in 130 B.C. when each of them produced a drama: Pacuvius was eighty years old and at the end of his career, and Accius, aged thirty, was making his debut. With Accius, the popularity of the fabula cothurnata reached its height, and in later years, Romans looked back on the second half of the second century B.C. as the Golden Age of Tragedy. Only fragments of the plays survive, however.

Greek Theater in Ancient Rome

There is funerary inscription on the tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundio in Pompeii saying that he was a patron of the arts, paying for ludi — musical or theatrical events that were performed in Latin and, significantly, in Greek. “This is the first time we have this direct evidence of Greek plays in Pompeii,” Gabriel Zuchtriegel, Pompeii’s director said. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021]

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: “Scholars had hypothesized, based on evidence in wall paintings and graffiti, that such events took place, but the inscription provides exciting confirmation. Zuchtriegel went on, there was a fashion in the Roman Empire for Greek-language performance, which was established by the emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 A.D., and who fancied himself not just an aficionado of Greek drama and song but also a performer. (According to the historian Suetonius, Nero “made his début” as a singer in Naples, so enjoying himself onstage that he ignored the rumblings of an earthquake in order to finish his performance.)

Nero’s reputation as a tyrant has lately been reconsidered by scholars, and the evidence of Greek-language ludi in Pompeii buttresses the revised image of the Emperor as a popular leader; it also underscores the extent to which even a provincial city like Pompeii was influenced by the cultural fashions of the capital. “Pompeii and Campania had this really multicultural environment,” Zuchtriegel said. “People came from the Eastern Mediterranean, and there were the old Greek colonies at Naples and Paestum. We have evidence of Jewish people here at Pompeii.” (Graffiti found in the city cite individuals with the names Sarah, Martha, and Ephraim.)

Plautus — the Flatfoot Clown — Rome’s First Noteworthy Writer?

Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (died 184 B.C.) is ancient Rome's best-know playwright. He is said to have come to Rome from Umbria where he was born. He worked for a while in the theater business, tried to make a living as a trader but lost all his money, and was forced to work at a mill where he used his spare time to write plays. He died in 184 B.C.

Dr. Rich Prior of the Furman University Classics faculty wrote: “ In the year 254 B.C. in a tiny backwater town of north-central Italy named Sarsina was born a certain Titus. That was his name. Just plain Titus. As a young man, Titus was dissatisfied with his rural lot, so he decided to seek his fortune in the big city. When Titus arrived in Rome he found work first as a stage hand, then as an actor. At this point the Roman stage was occupied by a native Italian dramatic form called the fabula Atellana, a sort of variety show featuring singers, dancers, clowns, magicians, and skits with a generous amount of slapstick. Our boy Titus found his niche as a clown (maccus in Latin). He also acquired a nickname 'Flatfoot' (Plautus). When he became a citizen and had to pick a full and proper legal name by Roman custom, he stitched these together to become Titus Maccius Plautus, or Titus the Clown Flatfoot.

“Eventually Titus saved some cash, left the stage, and tried his hand at commerce. The venture failed miserably. Driven to desperation, he worked as a common laborer at a flour mill while studying Greek on the side. Greece had only recently been swept into the Roman world, and with Greece came all kinds of Greek goodies, including new dramatic forms. The Greek "New Comedy" was different. A single continuous story, all with the same stage set — 2 or 3 houses on a street. The Greek plays were funny enough, but the jokes were about Greek manners and ways. Titus thought Romans would enjoy them too, but only if they were adapted to a Roman context. The only catch was that the Romans were real fuddyduddies. Fine if the plays made fun of Greeks, but no one should poke fun at Romans. So, starting when he was about 40 years old, Titus found a way to reconcile it all. In a brilliant Victor/Victoria-esque manoeuvre, he replaced the Greeks in the plays with Romans, but dressed them up as Greeks, put them in Greek cities, and gave them Greek names. The veneer was thick enough to satisfy the curmudgeons, but thin enough to let the essential Romanness shine through. He added some innovations of his own as well, such as audience involvement and saucy, clever slaves who always come up smelling like roses.

Plautus Comedy

Plautus wrote over a hundred plays before he died in 184 B.C.. Unfortunately only 20 survive intact, and these represent the oldest complete works of Roman literature. According Encyclopedia.com: It is impossible to judge how much Plautus adapted his Greek originals for Roman taste, but his plays ostensibly have Greek settings such as Athens or Epidamnus. While they could be any city, much of the slapstick must come from the Atellanae, the popular Atellan farces. Plautus used the stock characters of the New Comedy but he put his own mark on them. His courtesans are not always sweet and alluring; in the Truculentus a ruthless courtesan brings her lovers to ruin. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

One favorite character type that Plautus developed brilliantly was the clever slave. He also reintroduced song into comedy. There had been songs in Old Comedy but they had fallen by the wayside. Plautus found that the Roman audience liked musical comedy and inserted songs more and more as time went on. The Boastful Soldier, which was an early play, has no songs; the Brothers Menaechmus, which is later, has five. His dialogue is racy but not dirty, for the Romans were still puritanical, and as the plots of Plautus' comedies unfolded onstage, many Romans must have reflected that such things happened in Greece but never in Rome, and found satisfaction in the sense of moral superiority.

Plays by Plautus

scene from Plautus's Cistellaria

Braggart Soldier focuses on mercenary soldier who is all bombast and self-advertisement. According to Encyclopedia.com: In this case, the soldier of the title has the mouth-filling name of Pyrgopolynices. A young Athenian, Pleusicles, is madly in love with a courtesan Philocomasium, but while he is away from Athens on official business, the soldier abducts her to Ephesus. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Pleusicles' clever slave, Palaestrio, sets off to tell his master what happened, but he is captured by pirates. Coincidentally, they present him to Pyrgopolynices. Palaestrio gets a letter to Pleusicles summoning him to Ephesus. Pleusicles arrives and lodges at a friend of his father's, who lives next door to the soldier. The clever slave Palaestrio arranges an elaborate hoax to make the soldier believe the wife of a wealthy old gentleman has fallen desperately in love with him. The wife is actually a courtesan who plays the role that Palestrio has assigned her, and the old man is the friend of Pleusicles' father. The soldier readily gives up Philocomasium for his new love, but he is caught red-handed attempting adultery, given a sound beating, and threatened with castration. The old man relents when Pyrgopolynices swears never to seek revenge for the beating he received.

Brothers Menaechmus is one of Phis better known plays. “Very little tinkering was necessary to make the play work on the modern stage”. The main characters are: 1) Prologa, speaker of the prologue; 2) Peniculus, a parasite; 2) Menaechmus I, a twin; 3) Erotium, a courtesan; 4) Cylindra, a cook; 5) Menaechmus II, a twin; 6) Messenio, his slave; 7) Matrona, wife to Menaechmus I; 8) Ancilla, slave to Erotium; 9) Senex, Matrona's father; 10) Medicus, a physician; 11) Ruffiana, a slave; 12) Decia, another slave; 13) Thalia, yet another slave; and 14 ) Dulcia, still one more slave.

According to Encyclopedia.com: The Brothers Menaechmus is a comedy of mistaken identities; it was adapted and elaborated by Shakespeare in his Comedy of Errors. Identical twins were born to a Sicilian merchant from Syracuse. One twin, Menaechmus, was kidnapped and his father died of grief. Thereupon the grandfather of the remaining twin renamed him Menaechmus to commemorate his lost brother. Thus we have Menaechmus I and Menaechmus II, identical siblings. Menaechmus I, the boy who had been kidnapped, was taken to Epidamnus by his abductor, who, it turned out, had no son, and so he adopted Menaechmus I and made him heir to his enormous fortune. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

When the play opens, Menaechmus II has come to Epidamnus in search of his twin; this is the sixth year he has been searching. Menaechmus I is having an affair with a courtesan, Erotium. Erotium mistakes Menaechmus II for Menaechmus I, and Menaechmus II goes along with the error; he has lunch with Erotium and enjoys her favors. The deception results in all manner of confusion so that when Menaechmus I returns to the stage he encounters a jealous wife, an irritated mistress, and a father-in-law who thinks he's insane. He escapes being dragged off to a doctor, a fate worse than death, by the intervention of Menaechmus II's slave. Finally the two Menaechmuses meet and sort things out. The drama comes with an assortment of stock characters: a parasite, an alluring courtesan, and a silly doctor. It is Plautus' only comedy of errors, and when Shakespeare adapted it, he doubled the scope for mistaken identities by having not one set of identical twins but two.

Plautus Plays (d.184 BCE): The Brothers Menaechmus 199 translation,, was at Rhodes, now Internet Archive web.archive.org

Plautus (d.184 BCE): Aulularia Internet Archive web.archive.org

Terence and His Plays

The remaining eight comedies that were have today are by Publius Terentius Afer, who was born in Carthage and brought as a boy slave to Rome by a senator who was so impressed by the boy’s wit and intelligence that he gave him a good education and freed him. Before he was 25, he produced six plays. He then left Rome for Greece, never to return. Various reports were told about his death, but they agree that he was carrying a large number of new plays in his baggage — translations from the Greek — that were lost with him.[Source: Encyclopedia.com]

According to Encyclopedia.com: All six plays that Terence wrote have survived, which is a remarkable tribute to his staying power through the Middle Ages. His comedies did not have the popular appeal that Plautus' plays did, for they lacked his "comic power" as one ancient critic said. They were, however, well-constructed, polished dramas written in the sort of Latin that one could hold up to schoolboys as a model.

His first play, the Woman of Andros (Andria) produced in 166 B.C., was based on two of Menander's plays, and uses stock characters with originality: there is the typical lovesick young man, but he wants to marry a young woman of good family, not a courtesan. The strict fathers are presented with sympathy, and the clever slave is more than a mere trickster. The plot is as follows: Simo has betrothed his son Pamphilus to Philumena, daughter of Chremes. But Pamphilus loves Glycerium, an orphan, whereas his friend Charinus wants to marry Philumena. The two fathers negotiate; the clever slave Davus orchestrates the action and everything is resolved when Glycerium turns out to be Chremes' daughter and also to have borne a child to Pamphilus. Pamphilus marries Glycerium and Charinus marries Philumena. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The year after the Woman of Andros, Terence produced his Mother-in-Law but it failed at its first production. Then came the Self-Punisher and the Eunuch and in the same year as the Eunuch, the Phormio. His last play was the Adelphi (The Brothers) which many critics consider his best. In that play, there are two sets of brothers. One set is elderly with contrasting characters: Micio who lives in Athens and is easy-going, and Demea, a farmer outside Athens who is frugal. Micio has no son of his own and adopts one of Demea's two sons. Thus we have a second set of brothers: one brought up virtuously by his father and the other indulgently by his adoptive father who is also his uncle. The plot centers about the attempt of Micio's adoptive son to kidnap a harp-playing girl for his virtuous brother. The plot is resolved when Demea is converted to a more indulgent attitude, his son keeps his harpist, and Micio's adoptive son gets married.

The accidents of survival make it appear that dramatic genius dried up after Terence. In fact, theater continued to be popular. While Terence was writing comedies that were purely Greek in everything except the language, other playwrights were putting Roman characters on stage. These were called fabulae togatae, that is, dramas in togas, in contrast to the fabulae palliatae where the characters wore Greek fashions. Their success was modest. Crowds were more attracted to mime and Atellan farce.

Actor-Idols of Ancient Rome

The great actors of the Roman Empire grew out cantica singers in Roman opera. In the time of Caesar and Augustus,tThe cantica were more and more trimmed to the measure of the star singer on whom fell the burden of the effort and the honor of success. More and more he refused to have any but supernumeraries round him, the "pyrrhicists" who swayed to his cadence and to his command, the symphoniaci who replied to him and took up his motifs, the instrumentalists of the orchestra who relieved or accompanied him; zither players, trumpeters, cymbalists, flutists, and castanet-players (scabettarii). All were but satellites revolving round one sun. It was the soloist alone who filled the stage with his movement and the theater with his voice. He alone incarnated the entire action, whether singing, miming, or dancing. He prolonged his youth and preserved his slimness by a strict diet which banned all acid foods and drinks and which called for emetics and purgatives the moment his waistline was threatened. Faithful to the most severe training, he exercised unremittingly to preserve the tone of his muscles, the suppleness of his joints, and the volume and charm of his voice. Skilled in personifying every human type, in representing every human situation, he became "the pantomime" par excellence, whose imitations embraced the whole of nature, and who created a second nature with his phantasy. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Though the law still called him an "actor" and labeled him "infamous," the star of the Roman stage inevitably became the hero of the day and the darling of the women. In Augustus' time the city was full of the fame, pretensions, and squabbles of the pantomime Pylades. Under Tiberius the mob came to blows over the comparative merits of rival actors and the riot became so serious that several soldiers, a centurion, and a tribune were left dead on the streets. Dearly as Nero envied their notoriety, he had nevertheless to issue a decree of banishment against them, to put an end to the bloody affrays caused by their rivalries. But neither emperor nor public could do without them. Soon after exiling them, he recalled them and admitted them to the intimacy of his court, thus providing the first example of what Tacitus called histrionalis favor, this incurable idolatry which toward the end of the first century drew the empress Domitia into the arms of the pantomime Paris.

It cannot be denied that there were some great artists among these actor-idols of the Roman populace. Pylades I, for instance, certainly ennobled "the pantomime," a genre which he introduced into Rome. Several anecdotes illustrate his conscientiousness and the thought he gave to his art. One day his pupil and rival, the pantomime Hylas, while rehearsing before him the role of Oedipus, was displaying a fine self-confidence. Pylades chastened him by saying simply: "Don’t forget, Hylas, you are blind." Another day Hylas was playing a pantomime whose last line, "Great Agamemnon," was in Greek. Wishing to give full force to his final verse, he drew himself up to his full height as he delivered it. Pylades, seated among the stalls of the cavea as an ordinary spectator, could not refrain from calling out: "Ah, but you are making him tall, not great!" The audience, catching the comment, insisted on his mounting the stage to reenact the scene; when Pylades came to that passage he merely assumed the attitude of a man sunk in meditation for it is the duty of a chief to think beyond his fellows and for everyone.

Bawdy Pantomimists of Ancient Rome

Mime is a word used to denote both a type of show and the actor in it. It was a farce, modelled as closely as possible on reality. It was, properly speaking, a "slice of life" which was transported hot and spicy onto the stage, and its success depended on its realism, or naturalism, if the term is preferred, which grew steadily more and more marked. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The whole conception of the mime, with its flaunting of convention and its aiming at simplicity, certainly contained fertile seeds of theatrical reform. Two at least of the authors of mimes at the end of the first century B.C., Decimus Laberius and Publilius Syrus, lifted their pieces to the dignity of literature. But the more popular the mime became, the smaller was the part the text played in it. The great mimes I have quoted were those in which the authors played their own plays. The imperial mime actors brought to their sketchy plot "words and action which they had mentally pieced together, and according to the mood of the moment and the temper of the public embroidered them with improvisations on the theme announced.

In the mime, conventions were abolished. The actors had no masks and wore the contemporary dress of the town. Their number varied with the play, and they formed a homogeneous troupe. Women's roles were taken by actresses whose reputation for light virtue was well established by the time of Cicero. He himself was not insensible to the talent of Arbuscula or the charms of Cytheris, and was prepared to take up the defence of a citizen of Atina guilty of abducting a mimula, in the name of a right consecrated by the custom of the municipia 2 The subjects of the mimes were taken from the commonplace events of daily life, with a distinct leaning toward the coarser happenings and the lower human types: "a diurna imitatione vilium rerum et levium personarum." The treatment was usually caricature, which was pushed, as we shall see, to the limit of accuracy and impudence. Politics were permitted. Under the republic the mime was often critical of the government, and Cicero expected to gauge from its comments the reaction to the murder of Caesar. Under the empire, however, the mime had no option but to range itself on the side of the princeps, lampooning those who were in bad odour at court. The mime-actor Vitalis boasted of being particularly successful in this sort of target practice: "The man whom I took off and who saw his own image doubled under his very eyes was horrified to see that I was more truly he than he himself." In my opinion it is no accident that the mime most often played from 30 to 200 A.D., the Laureolus of Catullus, which was staged under Caligula and well known to Tertullian, demonstrated by the fate which overtook the brigand hero that under a good government the wicked are punished and the police always have the last word.

The Urbs delighted in the mimes acted by Latinus and Panniculus, which were filled with stories of kidnappings, cuckolds, and lovers hidden in convenient chests. In these plays the actresses were permitted to undress entirely (ut mimae nudarentur) which had formerly been tolerated only during the midnight games of the Floralia. The alternative was roughhouse, where loud words resounded and actual blows were exchanged, until finally the scrapping became serious and blood was shed copiously. The fact that the Laureolus remained popular for nearly two centuries is explained by the ferocity of its brigand murderer and incendiary and by his hideous punishment. Domitian allowed the play to end with a scene in which a criminal condemned under the common law was substituted for the actor and put to death with tortures in which there was nothing imaginary. The spectators were not revolted by the ignoble spectacle of a pitiable Prometheus derided, torn by the nails which pinned his palms and ankles to the cross, or seared by the claws of the Caledonian bear to which he had been flung as prey; in fact, Martial sings the praises of the prince who made these things possible. So performed, the mime seemed to the Romans of the time to reach the highest perfection attainable by the means and the effects at its disposal ; and indeed, this slice of life cut from the living flesh leaves far behind the most graphic horrors portrayed today. As the mime reached the height of its achievement, it drove humanity as well as art off the Roman stage. It plumbed the depths of a perversion which had conquered the masses of the capital. They were not sickened by such exhibitions because the ghastly butcheries of the amphitheater had long since debased their feelings and perverted their instincts.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024