Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

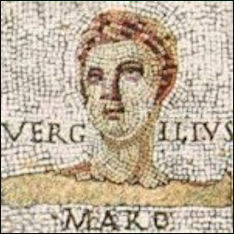

VIRGIL

Virgil Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), usually called Virgil or Vergil in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. Regarded as the greatest Roman writer, he is credited with transforming myth into literature. He wrote three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: the Eclogues, the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid. The “ Aeneid” , which appeared after his death and is regarded as a model of writing in the Latin style.

Virgil saw himself as an outsider in Rome. He was born Publius Vergilius Maro in the village of Andes near Venice. His father was a farmer wealthy enough to pay for an education for his son. Virgil studied at Cremona and Milan before moving at the age of 17 to Rome, where he studied rhetoric and philosophy but didn’t stay all that long.

After the Roman civil war between Caesar and Pompey, Virgil’s father’s farm was seized. The loss meant that he could no longer pay for Virgil’s education. Some powerful people in Rome sympathized with Virgil’s plight and helped his father obtain a new farm. These friends also introduced Virgil to Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus. One of Augustus’s ministers became one of Virgil’s best friends. He was also the writer’s benefactor, freeing Virgil from worries about money

According to one old story Virgil held a funeral for a common housefly which he claimed was his favorite pet. Mourners and an orchestra were hired; celebrities and statesmen were on hand; special eulogies were read by prominent citizens; and finally the fly was buried in special mausoleum. The cost of the funeral? About 800,000 sesterces (around $200,000 in today's money). [People's Almanac]

Websites on Ancient Rome:

Theoi Classical Texts Library, translations of works of ancient Greek and Roman literature, with an impressive gallery of illustrations Internet Archive web.archive.org ;

Tools of the Trade for the Study of Roman Literature, by Lowell Edmunds and Shirley Werner, Internet Archive web.archive.org ;

Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org

Virgil (70-19 B.C.)

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): The Aeneid John Dryden translation (1976) MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): The Aeneid John Dryden translation (1976) Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): The Aeneid J. W. Mackail translation (1885) Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): The Aeneid E. F. Taylor translation (1907) Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): The Aeneid Rolfe Humphries translation (1951) Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

See 2ND Aeneid: Study Guide Brooklyn College, Internet Archive web.archive.org;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): Eclogues MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): Eclogues [At Theoi] Internet Archive web.archive.org;

Virgil (70-19 B.C.): Bucolics and Eclogues in English Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Aelius Donatus (fl. 350 A.D.): Life of Virgil, tr. David Wilson-Okamura [At Virgil.org] Internet Archive web.archive.org;

WEB Virgil Home Page Internet Archive web.archive.org With links to all texts in both Latin and English.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Aeneid” (Penguin Classics) by Virgil (19 BC), first rate translation by Robert Fagles Amazon.com

“Aeneid” translated in verse by Sarah Ruden, a poet (Yale University Press) Amazon.com;

“The Death of Virgil” by Hermann Broch (1945) Amazon.com

“Virgil: His Life and Times” by Peter Levi (2001) Amazon.com;

“Virgil: A Life” by Peter Levi (2012) Amazon.com;

“Study Guide: Aeneid by Virgil” by SuperSummary (2020) Amazon.com;

“Georgics” (Oxford World's Classics) by Virgil Amazon.com;

“The Eclogues of Virgil” (English and Latin Edition), translated by David Ferry (2000) Amazon.com;

“Augustan Culture” by Karl Galinsky (1996) Amazon.com

“Livy: The Early History of Rome, Books I-V” (Penguin Classics)

by Titus Livy , Aubrey de Sélincourt , et al. (2002) Amazon.com

“The Iliad” translated Stanley Lombardo (1997) is regarded as the most accessible translation. Amazon.com;

“Homer: Poet of the Iliad” by Mark W. Edwards (John Hopkins University Press, 1990) Amazon.com;

“Troy: The Greek Myths Reimagined” by Stephen Fry (2021) Amazon.com;

“Latin Literature: An Anthology” (Penguin Classics) by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature” by J. C. Mckeown Peter E. Knox Amazon.com;

“Roman Literary Culture, second edition: From Plautus to Macrobius” by Elaine Fantham | (2013) Amazon.com;

Virgil’s Life as a Writer and Death

Using the Greek poet Theocritus as his model, Virgil wrote “ Eclogues” , pastoral poems describing the beauty of Italy. He followed that with “ Geogics” , more serious and original poems about farming and the Italian countryside. This work established Virgil as a famous poet.

Virgil’s life was devoted to writing. He never married and few events of his life seemed worth recording. He lived in Naples during the 12 years it took to write the “Aeneid”. Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome took an interest in Virgil’s work and asked that parts of be read to him as it was being written. August served as Virgil's patron and considered himself a direct descendant of Aeneas. Virgil's Aeneid glorified not just Rome but also Augustus, whose reign was portrayed as the fulfillment of the grand Roman destiny that the gods had predicted long ago.

Virgil was still working on the text when he died. The “Aeneid” wasn’t published until after his death. Virgil became ill and died while taking a trip to Greece and Asia Minor to verify facts for his book. In his will he bequeathed one quarter of his property to the Emperor Augustus. Virgil asked that the “ Aeneid “ be burned after his death because it wasn’t perfect. This request on the orders of Augustus was denied.

The “ Aeneid” had a big impact on Latin literature and Virgil’s legacy. It became the standard by which all other Latin literature was measured and lived on well past the Roman age. The Christian church called Virgil divinely inspired. Dante chose Virgil to be his guide in Hell and Purgatory in the “ Divine Comedy” . Virgil’s work also had a big influence on Chaucer, Milton, Tennyson and others. In the Middle ages, his tomb in Naples became a religious shrine believed to be endowed with magical powers.

Virgil and the Aeneid

In approximately 30 B.C., Virgil began composing the Aeneid, an epic poem that told the story of Aeneas and the founding and destiny of Rome. According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: Using myth, history, and cultural pride, the Aeneid summed up everything the Romans valued most about their society. At the same time, it offered tales of adventure featuring gods and goddesses, heroes and ghosts, warriors and doomed lovers. Virgil died before finishing the work, but it established his reputation as the foremost poet of the Romans.[Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

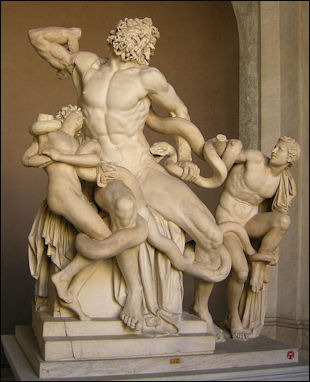

The Lacoon. a Greek work In the “Aeneid “ Virgil, a Roman, wrote:

“The Greeks shape bronze statues so real they

they seem to breathe.

And craft cold marble until it almost

comes to life.

The Greeks compose great orations.

and measure

The heavens so well they can predict

the rising of the stars.

But you, Romans, remember your

great arts;

To govern the peoples with authority.

To establish peace under the rule of law.

To conquer the mighty, and show them

mercy once they are conquered.”

The work also has some pretty graphic language. Describing the death of Euryalus, Virgil wrote:

He writhes in death

as blood flows over shapely limbs, his neck droops,

sinking over his shoulder,

limp as a crimson flower

cut off by a passing plow.

Aeneid

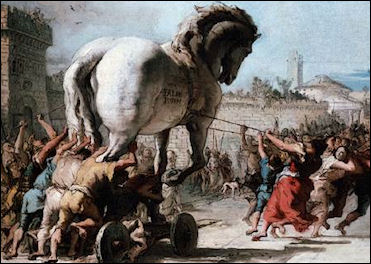

The Aeneid is a 12-volume book of poetry written (30–19 B.C.) by the Roman poet Virgil. Drawn from Homer's “ Iliad” , the “ Aeneid” attributes the origin of the Roman people to Aeneas, a hero of the Trojan War. Although it is set in the distant past it has many features of A.D. first century Rome. Homeric themes are presented in a Roman way and battles are fought like Roman battles. Some key facts are different. Virgil records the events of the “ Odyssey” as occurring before those in the “ Iliad” (the contrary is true in Homer’s books). Many of the details from events in the “ Iliad” , particularly the Trojan horse story, come to us from the “ Aeneid” not the “ Iliad”.

In the “ Aeneid” the Trojans have been kicked out of the their homeland because of the war and the end up in Italy, which is caste as a kind of Promised land. There, Aeneas marries an Italian princess and their descendants founded Rome. The Roman emperors embraced the story and used the links to the Trojans to legitimize their rule.

Virgil selected Aeneas, a son of Venus (Aphrodite) and a member of the Trojan royal family, because he seemed to be the only Trojan in the “Iliad” who had a future. He kept Aeneas true to his character in the “ Iliad” and made him one of the founders of the Roman race by incorporating an existing Roman tale about him.

Michael Elliot wrote in Time a common complaint of the generation that was required to study the classic in school: “At school, I loathed Latin, in general, but I detested Virgil in particular, After you’d spent hours wading through conjugations and declensions and ablative absolutes and gerund and parts perfect, imperfect and pluperfect, there was the pointless torture of learning and then reciting lines of dactylic hexameter about this bloke wandering aimlessly around the Mediterranean at the whim of a perpetually pissed off goddess. I mean, even Milton was more fun.”

Themes in the Aeneid

The basic theme in the “Aeneid” is that duty, honor and country have precedence above everything else. According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: As Rome was emerging as the leading power in the Mediterranean world in the 200s B.C., the Romans became eager to claim Aeneas and the Trojans as their ancestors. Some Romans even visited Ilium, a Roman city in Asia Minor said to stand on the ancient site of Troy, Aeneas's home city. A number of Roman writers contributed to the story of how Aeneas came to Italy so his descendants could build Rome.

Aeneas was an ideal figure to serve as the legendary founder of Rome. As the son of Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology), the goddess of love, and Anchises, a member of the Trojan royal family, he had both divine and royal parents. In addition, the ancient tales portrayed Aeneas as dutiful, spiritual, brave, and honorable, which were virtues the Romans believed characterized their culture. Finally, Aeneas was part of the Greek heritage so admired by the Romans. As a Trojan rather than a Greek, however, he provided the Romans with a distinct identity that was not Greek but equally ancient and honorable.

Trojan Horse by Giovanni Domenico Tipeolo It is widely accepted that Virgil wrote the Aeneid in an attempt to bring glory to the Roman culture in which he lived. Throughout the Aeneid, Virgil describes many prophecies, or predictions of the future. In all these prophecies, Rome becomes a great empire. The meaning of the prophecies is clear: Rome rules the world because it is fated to do so, a fact that has the support of the gods. At the end of the epic, Aeneas is able to marry Lavinia, a Latin princess. Their marriage symbolizes the union between the Latin and Trojan peoples, and their descendants represent the birth of the Roman Empire. In Book 4, after Aeneas and his followers leave Carthage, Dido kills herself in despair. This episode shows Aeneas's willingness to sacrifice his own desires to obey the will of the gods. It also creates a legendary explanation for the very real hostility between Carthage and Rome.

Aeneid Versus the Iliad and Odyssey

According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: Virgil modeled the Aeneid on the Iliad and the Odyssey, Homer's much-admired epics of ancient Greece. Like the Greek poems, the Aeneid features the Trojan War, a hero on a long and difficult journey, and exciting descriptions of hand-to-hand combat between brave warriors. It is also similar in form to the Greek epics: the twelve books of the Aeneid cover two major themes, the wanderings of Aeneas after the Trojan War, and the wars in Italy between the Trojans and the Latins.[Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

Roger Dunkle of Brooklyn College wrote: “Although the Aeneid shares many characteristics with the Homeric epic, as an epic it is different in important ways. For this reason, the Aeneid is referred to as a literary or secondary epic in order to differentiate it from primitive or primary epics such as the Homeric poems. The terms "primitive", "primary" and "secondary" should not be interpreted as value judgments, but merely as indications that the original character of the epic was improvisational and oral, while that of the Aeneid, composed later in the epic tradition, was basically non-oral and crafted with the aid of writing. As we have seen, the Homeric poems give evidence of improvisational techniques of composition1 involving the use of various formulas. This style of composition is suited to the demands of improvisation before an audience which do not allow the poet time to create new ways of expressing various ideas. In order to keep his performance going he must depend upon stock phrases, which are designed to fill out various portions of the dactylic hexameter line. On the other hand, Virgil, composing in private, obviously spent much time on creating his own personal poetic language. Thus in reading the Aeneid you will notice the absence of the continual repetition of formulas, which are unnecessary in a literary or secondary epic. [Source: Roger Dunkle, Brooklyn College Core Curriculum Series, 1986 /+]

“Whether the Homeric poems were originally improvised without the aid of writing or written down by the poet himself or dictated to a scribe and then recited, is not known for certain, but it is clear that they were composed in the style of improvised oral poetry. Virgil, however, does imitate Homeric language without the repetitions. This is another reason for calling the Aeneid a secondary epic. For example, Virgil occasionally translates individual Homeric formulas or even creates new formulas in imitation of Homer such as "pious Aeneas", imitates other Homeric stylistic devices such as the epic simile and uses the Homeric poems as a source for story patterns. Although in this sense the Aeneid can be called derivative, what Virgil has taken from Homer he has recast in a way which has made his borrowings thoroughly Virgilian and Roman. For example, Virgil changed the value system characteristic of the Homeric epic, which celebrated heroic individualism such as displayed by Achilles in the Iliad. The heroic values of an Achilles would have been anachronistic and inappropriate in a poem written for readers in Rome of the first century B.C., who required their leaders to live according to a more social ideal suited to a sophisticated urban civilization. Therefore, although Virgil set the action of his poem in a legendary age contemporary with the Trojan War before Rome existed, one must judge the characters of his poem by the standards of the poet's own times. “ /+\

Aeneas

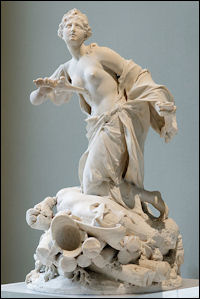

Death of Dido The hero Aeneas appeared in both Greek and Roman mythology as a Trojan leader. In Greek mythology, Aeneas was the son of Anchises (a member of the royal family of Troy) and the Venus, the goddess of love, . A character in Homer’s Iliad active in the defence of Troy, Aeneas escaped Troy after it fell to the Greeks and wandered the Mediterranean for many years eventually ending up Italy. The Romans acknowledged Aeneas and his Trojan company as their ancestors. The exploits of Aeneas form the basis of the Aeneid.

According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: Like many legendary heroes, Aeneas was a demigod, meaning he had one parent who was human and one parent who was a god. One day Aphrodite, saw Anchises on the hills of Mount Ida near his home. The goddess was so overcome by the handsome youth that she seduced him and bore him a son, Aeneas. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

Mountain nymphs raised Aeneas until he was five years old, when he was sent to live with his father. Venus had made Anchises promise not to tell anyone that she was the boy's mother. Still, he did so and was struck by lightning. In some versions of the legend, the lightning killed Anchises; in others, it made him blind or lame. Later variations have Anchises surviving and being carried out of Troy by his son after the war.

When the Greeks invaded Troy, Aeneas did not join the conflict immediately. Some versions of the myth say that he entered the war on the side of his fellow Trojans only after the Greek hero Achilles stole his cattle. Aeneas's reluctance to join the fighting partly came from the uneasy relationship he had with King Priam of Troy. Some sources say that Aeneas disliked the fact that Priam's son Hector was supreme commander of the Trojan forces. For his part, Priam disliked Aeneas because the sea god Poseidon had predicted that the descendants of Aeneas, not those of Priam, would rule the Trojans in the future. Nevertheless, during the Trojan War, Aeneas married Creusa, one of Priam's daughters, and they had a son named Ascanius.

Aeneas in the Greek and Roman Traditions

According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: The Iliad and other Greek sources provide a number of details about Aeneas's role in the Trojan War. According to Greek tradition, Aeneas was one of the Trojan leaders, their greatest warrior after Hector. An upright and moral man, Aeneas was often called “the pious” because of his respect for the gods and his obedience to their commands. In return, the gods treated Aeneas well. Some of the most powerful gods, including Apollo, Poseidon, and Aphrodite, Aeneas's mother, gave him their protection. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

There are various accounts of the last days of the Trojan War. One story relates that Aphrodite warned Aeneas that Troy would fall, so he left the city and took refuge on Mount Ida, where he established a new kingdom. In later years, several cities on the mountain boasted that they had been founded by Aeneas. Another version states that Aeneas fought bravely to the end of the war and either escaped from Troy with a band of followers or was allowed by the victorious Greeks — who respected his honor and religious devotion — to leave.

Over the centuries, a number of Roman myths developed about Aeneas. According to Roman tradition, Aeneas fought with great courage in Troy until messages from Aphrodite and Hector convinced him to leave the city. Carrying his father on his back and holding his son by the hand, Aeneas led his followers out of burning Troy. During the confusion, Aeneas's wife Creusa became separated from the fleeing Trojans. Aeneas returned to search for Creusa but could not find her. Aeneas and his followers found safety on Mount Ida, where they settled and began building ships. After several months, they set sail to the west. Dreams and omens (mystical signs of events to come) told Aeneas that he was destined to found a new kingdom in the land of his ancestors, the country now known as Italy.

Story of the Aeneid

Virgil After the fall of Troy, the Trojan hero Aeneas sets sail in search of a new home. After a fierce storm sent by Juno, the queen of the gods, he becomes separated from his crew. Early in the story, Virgil establishes the fact that Juno does her best to ruin Aeneas's plans because of her hatred for the Trojans, while Venus supports him. Jupiter, the king of the gods, reveals that Aeneas will ultimately reach Italy and his descendants will found a great empire.

In Book 1 of the Aeneid, Aeneas and his followers arrive in Carthage in North Africa after escaping the storm. Carthage is made invisible by magic and ruled by Queen Dido. In Book 2, Aeneas tells Dido how the Greeks won the Trojan War and how he escaped Troy. In Book 3 Aeneas tells Dido of earlier attempts by the Trojan survivors to found a city.

Book 4 reveals that Dido is in love with Aeneas, and the two become lovers. He helps her build a royal city. Jupiter’s gets angry about this as Aeneas has become side sidetracked from his duty to found the Roman Empire. Jupiter sends Mercury, the messenger of the gods, to tell Aeneas to quit dawdling and get over to Italy. Dido ultimately feels betrayed by Aeneas. When Aeneas leaves, according to one telling of the story, Dido flies into flurry of rage and grief and kills herself.

Aeneas and his companions settle briefly in Thrace, Crete and Italy before finally choosing Rome as their home. In Book 5 of the Aeneid, the Trojans reach Sicily and Aeneas organizes funeral games to honor his father, Anchises. While the games are in progress, Juno attempts to destroy the Trojan fleet, but Jupiter saves most of the ships and the Trojans depart. In Book 6, the Trojans arrive at Cumae in Italy and Aeneas visits the shrine of the Cumaean Sibyl, a famous oracle, who leads him on a visit to the underworld, where he meets up with the ghost of Dido, who turns away and would not speak to him, and the ghost of his father Anchises, who told him that he would found the greatest empire the world had ever known.

Aeneas Founds Rome

Books 7 through 11 tell of the Trojans' arrival in Latium, the kingdom of the Latins in western Italy. Encouraged by his father's prophecy, Aeneas goes to Latium and helps King Latinus of the Latins fight against outsiders. Turnus, the leader of another tribe called the Rutuli, launched a war against the Trojan newcomers, sparked by the meddling of Juno. Venus helps Aeneas by giving him a new set of armor and weapons bearing images of Rome's future glory. Jupiter then forbids the gods to interfere further. Some of the Latins also fought the Trojans, but Aeneas, exhilarated by having finally arrived at his destiny, refused to be defeated. After he killed Turnus he marries Latinus’s daughter Lavinia and founds the city of Lavinium, where Latins and Trojans are united. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

Aeneas inherits Latinus’s kingdom when Latinus dies, ruling over a kingdom of united Trojans and Latins. After this Aeneas visits the underworld and sees the heroes of Rome’s future. He returns with knowledge of magic and shamanism. Aeneas’s story ends when he is killed in a battle with Etruscans. When Aeneas catches a glimpse of Dido in the underworld he explains: “Oh dear god, was it I who caused your death?/ I swear by the stars, by the Powers in high...I left your shores, my Queen, against my will...Stay a moment. Don’t withdraw from my sight.”

After Aeneas's death, his son Ascanius ruled Lavinium and founded a second city called Alba Longa, which became the capital of the Trojan-Latin people. These cities formed the basis of what came to be ancient Rome. Some legends claim that Aeneas founded the city of Rome itself. Others give that honor to his descendant Romulus. Roman historians later altered the story of Rome's origins to make Ascanius the son of Aeneas and Lavinia, thus a Latin by birth. Ascanius was also called Lulus, or Julius, and a clan of Romans called the Julians claimed to be his descendants. Julius Caesar and his nephew Augustus, who became the first Roman emperor, were members of that clan. In this way, the rulers of Rome traced their ancestry and their right to rule back to the demigod Aeneas.

Historical Background of the Aenied

According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: Virgil first wrote the entire Aeneid in prose, using normal sentence structure and format, and then turned it into verse a few lines at a time. As he lay dying, Virgil requested that the manuscript of his still-unfinished work be destroyed. Nevertheless, the emperor Augustus preserved the work and had it published soon after Virgil's death in 19 B.C. Augustus' decision was no doubt based on the unstable situation in late Republican Rome (91-30 B.C.) and the need for a unifying myth that all Romans could rally behind. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

Aeneas' Flight from Troy

Rome had gone through a chaotic period during Virgil's life, including a series of civil wars, the assassination of Julius Caesar, and the fall of the Republic. Augustus, Julius Caesar's adopted great-nephew and successor, had to battle powerful rivals, including General Marc Anthony, for complete control of the newly created Roman Empire. After he solidified his power, he declared it his goal to purify Rome and restore its morality. The Aeneid helped proudly define Rome and unify the many groups within the empire who had squabbled for so long.

Roger Dunkle of Brooklyn College wrote: “Virgil lived through the politically violent and chaotic years of the failing Republic, and his writings very clearly show the influence of the events of this period. Thus, an understanding of the history of this era is critical to the interpretation of the Aeneid. In 63 B.C. a conspiracy to overthrow the Roman government led by the infamous Catiline was discovered and defeated through the efforts of Cicero, the consul of that year. There were, however, other threats to the existing order soon to follow. After the powerful general Pompey returned from his extensive conquests in the East in 62 B.C., the refusal of the Senate to approve his settlement of affairs there alienated him from the optimates. As a result, he joined in political alliance with the leaders of the Populares: Julius Caesar and Marcus Crassus. The alliance has come to be known as the First Triumvirate and was sealed by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter.3 Employing the threat of Pompey's military power, these three men were able to impose their will on Rome. In this way Caesar insured his own election to the consulship in 59 and in the following year, his assignment to the governorship of Gaul, which required the command of a large army to subdue the warlike natives. Caesar enjoyed great military successes against the Gauls for almost a ten-year period, but what meant most to him was the fact that he now had an army loyal to himself, making him equal to Pompey, who had for so long overshadowed him in military power. [Source: Roger Dunkle, Brooklyn College Core Curriculum Series, 1986 /+]

“When Virgil has Anchises predict the civil war between these two leaders, their names are not mentioned, but they are referred to as father-in-law and son-in-law (6. 828-831). In the late 50's B.C. with Caesar in Gaul and Pompey virtually ruler at Rome, a split between the two leaders became increasingly evident, especially after the death of Caesar's daughter, which removed the last tie between them. Civil war was inevitable. As the poet Lucan put it: "Caesar is able to tolerate no man as his superior; Pompey, no man as his equal" (1.125-126). The war between Caesar and Pompey ended with the latter's defeat in Greece and his assassination in Egypt. After his victory Caesar assumed the dictatorship at Rome, which ultimately was granted to him for life. Caesar was now sole ruler of Rome. Resentment at the loss of political freedom resulted in his assassination by Brutus, Cassius, and others in 44. /+\

“Caesar's army passed in good part into the possession of his eighteen-year- old grand-nephew, Octavian, his chief heir, who was adopted as Caesar's son according to the terms of his will. Because of his youth, no one expected Octavian to be of any consequence in the political arena, but with a maturity beyond his years he won over Caesar's veterans and was determined to avenge his adoptive father's death. Octavian came into immediate conflict with Caesar's lieutenant, Antony, who felt that his close association with the dictator earned him the right to succeed Caesar. Cicero sided with Octavian and attacked Antony in a set of speeches called the Philippics, which resulted in Antony's being declared a public enemy. After Antony suffered a defeat at the hands of a coalition of military leaders (including Octavian), Antony and Octavian decided it would be in their own best interests to join in political alliance. They along with Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate (43 B.C.) and revived Sulla's technique of proscription in order to rid themselves of their political enemies. One of the most prominent victims of this proscription was Cicero himself, whose death was demanded by Antony in revenge for the Philippics and reluctantly agreed to by Octavian. At Antony's command Cicero's head and hands were cut off and placed on the speaker's platform in the Forum. This barbaric act serves as a vivid symbol of the bloody violence of the last years of the Republic. /+\

“Following the proscriptions Antony and Octavian turned their attention to the assassins of Caesar and defeated them in Greece at the battle of Philippi (42 B.C.). Their alliance was weakened when Antony's brother revolted against Octavian while Antony was in Egypt, but was reconfirmed by the marriage of Antony and Octavian's sister. There were two more temporarily successful attempts to prevent a split between Octavian and Antony, but Antony's romantic involvement with Cleopatra,4 the queen of Egypt, which resulted in his rejection and ultimate divorce of Octavia, permanently alienated the two leaders. In addition, Antony's obvious intention to use the wealth of Egypt as a basis of power for uniting the East under his control made war unavoidable. The final conflict was a naval battle off Actium (31 B.C.) on the western coast of Greece, in which Antony and Cleopatra were routed by Octavian's fleet. The defeated pair later committed suicide in Alexandria. /+\

“Cleopatra was a member of the Ptolemies, the Greek ruling family of Egypt, which had controlled Egypt since the death of Alexander the Great. As was the custom, she was married to her brother Ptolemy XIII, and after his death, to another brother Ptolemy XIV. During his campaign in the East after his victory over Pompey, Julius Caesar had an affair with her and fathered a son. /+\

“After Actium Octavian embarked on a program of restoring order by reuniting the Roman present with its old moral, religious and political traditions. He made a show of restoring the free Republic, but Octavian with his control over the Roman army and finances was in fact the sole ruler of Rome and its empire. In 27 B.C. the Roman Senate bestowed upon him the honorific title of Augustus, which symbolized his special position of authority in the state. Octavian was welcomed as a savior by such writers as Virgil and Horace, the great lyric poet, and by the vast majority of Romans, because he had brought peace to Rome after a century of civil conflict. The admiration expressed by the poets for Octavian's accomplishments, although its effusiveness is sometimes offensive to modern taste, should not be interpreted as mere servile praise and political propaganda, but as an honest appreciation of a political leader who had brought an end to the horrors of civil war and was able to act with moderation after his victory. /+\ The title "Augustus" had special religious associations and was etymologically related to the Latin word auctoritas 'authority'.” /+\

Dido

Reading the Aeneid

Roger Dunkle of Brooklyn College wrote: “The Aeneid differs from the Iliad and the Odyssey in that it often gives evidence of meaning beyond the narrative level. Homeric narrative is fairly straightforward; there is generally no need to look for significance which is not explicit in the story. On the other hand, although Virgilian narrative can be read and enjoyed as a story, it is often densely packed with implicit symbolic meaning. Frequently the implicit reference is to Roman history. While Homer is little concerned with the relationship of the past to the present - the past is preserved for its intrinsic interest as a story - Virgil recounts the legend of Aeneas because he believes it has meaning for Roman history and especially for his own times. For example, the destruction of Troy resulting in the wanderings of Aeneas and his followers west to find a new life can be seen as parallel to the history of Rome in the first century B.C., which included both the violent destruction of the Republic and the creation of peace and order by Augustus. Also suggestive of the Roman civil wars is the "civil war" between the Trojans and their Italian allies, and Aeneas's victory over the Italians in this war suggests Augustus's ending of the Roman civil wars. The Carthaginian queen Dido, whose beauty almost makes Aeneas forget his duty as a leader, reminds the reader of Cleopatra's similar relationship with Antony. Dido's story also provides a legendary explanation for the historical hostility between Rome and Carthage which resulted in three wars. These are only a few examples of the importance of Roman history in the Aeneid. In the questions at the end of this section help will be provided to enable you to see other implicit allusions to Roman history. [Source: Roger Dunkle, Brooklyn College Core Curriculum Series, 1986 /+]

“Another important difference between the Aeneid and the Homeric poems is that the former has a philosophical basis while the latter were composed in an era completely innocent of philosophy. The Aeneid gives evidence of the influence of Stoicism, a Hellenistic philosophy which had gained many adherents in the Greek world and by the first century B.C. had become the most popular philosophy of the educated classes at Rome. In reading the Aeneid be alert for Stoic influence. Note the connection between fate and the foundation of Rome. Also note when Aeneas adheres to Stoic ethical principles and when he does not. Finally, be sure to read carefully Anchises's digression on the nature of the universe and human existence (6.724-751), which combines Stoic physical theory with Orphic and Pythagorean teachings (transmigration of souls). On the other hand, the gods in the Aeneid for the most part do not reflect the Stoic view of divinity. They are basically the traditional anthropomorphic deities of myth as required by the conventions of epic. On occasion, however, Stoic influence is evident as in book 1 when Jupiter is closely identified with providential fate (1.262 ff.). /+\

“Another important aspect of the interpretation of the Aeneid is Virgil's use of the Homeric poems. In the Aeneid there are innumerable echoes of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Do not be concerned if you do not immediately recognize the allusions to Homer; it takes some experience and practice. Some echoes are so subtle that they go unnoticed even by experienced readers of the poem. Perhaps the most important connections for you to make will be in book 12 where your knowledge of the Iliad will enable you to see how important figures of Virgil's poem are associated in various ways with heroes of the Iliad. Once these connections are identified, you will see that these references to the Iliad provide an interesting and significant commentary on the action of the Aeneid. /+\

“Finally, you should be conscious of recurring images in the Aeneid such as snakes, wounds, fire, hunting, and storms, and their meaning for the narrative. In your study of the imagery notice the Virgilian technique of making a real part of the story an image and vice-versa. For example, consider hunting in the Aeneid. In book 1 Aeneas is a real hunter who slays deer; in book 4 in a simile he is a metaphorical hunter of Dido and then again a real hunter as he and Dido engage in a hunting expedition. No doubt Virgil intended these three instances of hunting to refer to each other implicitly and to comment upon the story. Recurring words have a significance in the Aeneid uncharacteristic of the Homeric poems, which, due to the nature of oral poetry, as a matter of course employ constant repetition of formulas. Of course, the reader in translation is at a disadvantage in this regard since translators often do not translate any given Latin word in the same way every time, but even if there is not consistent translation of a given Latin word, the concepts which these recurring words convey can be identified in translation. Two of the most important recurrent words in the Aeneid are furor, which means violent madness', frenzy', fury', passionate desire' etc., and its associated verb, furere to rage', to have a mad passion'. These words have important meaning for the characters in the Aeneid to whom they are applied and whose behavior must be evaluated by reference to the Stoic ethical ideal. In addition, these two words connect the legendary world of the Aeneid with Roman politics of the first century B.C. because they were often used in prose of the late Republic to describe the political chaos of that era. In reading the Aeneid try to be aware of interpretative points such as those described above. With attention to these details of interpretation you will begin to appreciate the art of Virgil and understand better the meaning of the poem.” /+\

Dido's sacrifice to Juno

Passage from the Aeneid

Virgil's Aeneid might be understood as one long paean, glorifying Rome, its founders, and its greatness in the Augustan age. How skillfully the courtly poet paid his tribute to the reigning Julii and especially to Augustus is shown in the following lines from the great Latin epic.

Virgil wrote in The Aeneid, VI.ii.789-800, 847-853:

[Anchises, in the realms of the dead, is reciting to his son Aeneas the future glories of the Roman race.]

“Lo! Caesar and all the Julian

Line, predestined to rise to the infinite spaces of heaven.

This, yea, this is the man, so often foretold you in promise,

Caesar Augustus, descended from God, who again shall a golden

Age in Latium found, in fields once governed by Saturn

Further than India's hordes, or the Garymantian peoples

He shall extend his reign; there's a land beyond all of our planets

[Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 174-179]

“Yond the far track of the year and the sun, where sky-bearing Atlas

Turns on his shoulders the firmament studded with bright constellations;

Yea, even now, at his coming, foreshadowed by omens from heaven,

Shudder the Caspian realms, and the barbarous Scythian kingdoms,

While the disquieted harbors of Nile are affrighted!

[Anchises now points out the long line of worthies and conquerors who are to precede Augustus, and adds these lines.]

“Others better may fashion the breathing bronze with more delicate fingers;

Doubtless they also will summon more lifelike features from marble:

They shall more cunningly plead at the bar; and the mazes of heaven

Draw to the scale and determine the march of the swift constellations.

“Yours be the care, O Rome, to subdue the whole world

for your empire!

These be the arts for you — the order of peace to establish,

Them that are vanquished to spare, and them that are

haughty to humble!

Another view of Dido's death

Impact and Influence of the Aeneid

According to the Encyclopedia of World Mythology: Whatever Virgil may have thought about his work while he lay on his deathbed, others quickly recognized that the Aeneid was a masterpiece. Romans loved the poem. It gave them an impressive cultural history and justified the proud expectation that they were destined to rule the world. Yet even after the Roman Empire fell, people continued to read and admire the Aeneid. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Mythology, Encyclopedia.com]

During the Middle Ages, many Europeans believed that Virgil had been a magician and the Aeneid had magical properties. This could be because the story contained so many omens, or mystical signs of events to come. People would read passages from the work and search for hidden meanings or predictions about the future. So admired was Virgil that the Italian poet Dante Alighieri, who wrote during the late 1200s and early 1300s, made him a central character in his own religious epic, The Divine Comedy. In Dante's work, Virgil guides the narrator through hell and purgatory, but he is not able to enter heaven because he was not a Christian.

The Aeneid influenced English literature as well. Poets Edmund Spenser and John Milton wrote epics that reflect the work's influence. Poet John Dryden was one of many who translated the Aeneid, and his 1697 version is one of the best English translations. By contrast, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron disliked Virgil's work, perhaps because it celebrates social order, religious duty, and national glory over the Romantic qualities that they favored: passion, rebellion, and self-determination. The Aeneid has inspired musical composers as well as writers, and many operas have been based on Virgil's work. Among the best known are Dido and Aeneas (1690), by English composer Henry Purcell, and The Trojans (1858), by the French composer Hector Berlioz.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024