Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

ANCIENT ROMAN LITERATURE

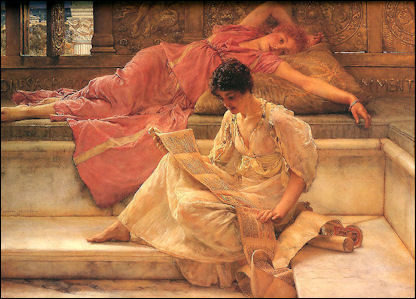

Favourite Poet by Lawrence Tadema-Jones The Romans produced great poetry and prose. We know more about them than any other ancient civilization because they left behind a vast amount of literary and historical works. However they did not have the same impact on literature as the Greeks. In fact a lot of their literature, like their art, is ignored today.

The Romans built great libraries with books they took from conquered territory and works they added themselves. By A.D. 350 there were 29 libraries in Rome. Literacy spread. The English historian Peter Salway has noted that England under Roman rule had a higher rate of literacy than any period until the 19th century.

Latin was less expressive and more difficult to play with than Greek. With its long monotonous syllables it required a special skill to produce poetry with life. Latin was better for expressing clear, precise thoughts rather than shades of meaning.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN CULTURE factsanddetails.com

LANGUAGE AND WRITING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

CLASSICS OF ROMAN LITERATURE europe.factsanddetails.com

SATYRICON europe.factsanddetails.com

AENEID: VIRGIL, STORY, HISTORY, THEMES europe.factsanddetails.com

POETRY OF ANCIENT ROME BY OVID, HORACE, SULPICIA, CATULLUS AND MARTIAL factsanddetails.com

SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

LUCRETIUS: THE GREAT POET AND ARTICULATOR OF EPICURIANISM europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

JUVENAL'S SATIRES europe.factsanddetails.com

DRAMA IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, COMEDY, PLAYWRIGHTS AND PLAYS europe.factsanddetails.com

THEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome:

Theoi Classical Texts Library, translations of works of ancient Greek and Roman literature, with an impressive gallery of illustrations Internet Archive web.archive.org ;

Tools of the Trade for the Study of Roman Literature, by Lowell Edmunds and Shirley Werner, Internet Archive web.archive.org ;

Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Latin Literature: An Anthology” (Penguin Classics) by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature” by J. C. Mckeown Peter E. Knox Amazon.com;

“Roman Literary Culture, second edition: From Plautus to Macrobius” by Elaine Fantham | (2013) Amazon.com;

“Literary and Artistic Patronage in Ancient Rome” by Barbara K. Gold (1982) Amazon.com;

“Cicero: Selected Works” by Marcus Tullius Cicero and Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“Aeneid” (Penguin Classics) by Virgil (19 BC) Amazon.com

“The Death of Virgil” by Hermann Broch (1945) Amazon.com

“Metamorphoses” by Ovid, 8 AD (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“Tales from Ovid” by Ted Hughes (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“The Golden Ass” (Oxford World's Classics) by Apuleius, translated by P. G. Walsh Amazon.com

“Terence and the Language of Roman Comedy” by Evangelos Karakasis (2005)

Amazon.com;

“Living Theatre in the Ancient Roman House: Theatricalism in the Domestic Sphere”

by Richard C. Beacham, Hugh Denard Amazon.com;

“Rome's Cultural Revolution” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (2008) Amazon.com

“Augustan Culture” by Karl Galinsky (1996) Amazon.com

History of Roman Literature

Before the Romans came into contact with the Greeks, they cannot be said to have had anything which can properly be called a literature. They had certain crude verses and ballads; but it was the Greeks who first taught them how to write. It was not until the close of the first Punic war, when the Greek influence became strong, that we begin to find the names of any Latin authors. The first author, Andronicus, who is said to have been a Greek slave, wrote a Latin poem in imitation of Homer. Then came Naevius, who combined a Greek taste with a Roman spirit, and who wrote a poem on the first Punic war; and after him, Ennius, who taught Greek to the Romans, and wrote a great poem on the history of Rome, called the “Annals.” The Greek influence is also seen in Plautus and Terence, the greatest writers of Roman comedy; and in Fabius Pictor, who wrote a history of Rome, in the Greek language. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)\~]

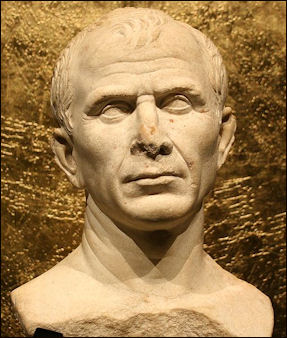

The most important evidence of the progress of the Romans during the period of the civil wars is seen in their literature. It was at this time that Rome began to produce writers whose names belong to the literature of the world. Caesar wrote his “Commentaries on the Gallic War,” which is a fine specimen of clear historical narrative. Sallust wrote a history of the Jugurthine War and an account of the conspiracy of Catiline, which give us graphic and vigorous descriptions of these events. Lucretius wrote a great poem “On the Nature of Things,” which expounds the Epicurean theory of the universe, and reveals powers of description and imagination rarely equaled by any other poet, ancient or modern. Catullus wrote lyric poems of exquisite grace and beauty. Cicero was the most learned and prolific writer of the age; his orations, letters, rhetorical and philosophical essays furnish the best models of classic style, and have given him a place among the great prose writers of the world. \~\

The reign of Augustus (27 B.C.–14 A.D.) was arguably the Golden Age of Roman literature. At this time was written Vergil’s “Aeneid,” which is one of the greatest epic poems of the world. It was then that the “Odes” of Horace were composed, the race and rhythm of which are unsurpassed. Then, too, were written the elegies of Tibullus, Propertius, and Ovid. Greatest among the prose writers of this time was Livy, whose “pictured pages” tell of the miraculous origin of Rome, and her great achievements in war and in peace. During this time also flourished certain Greek writers whose works are famous. Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote a book on the antiquities of Rome, and tried to reconcile his countrymen to the Roman sway. Strabo, the geographer, described the subject lands of Rome in the Augustan age. The whole literature of this period was inspired with a growing spirit of patriotism, and an appreciation of Rome as the great ruler of the world. \~\

Reign of Augustus — the Golden Age of Roman Literature.

The reign of Augustus (27 B.C.–A.D. 14) is often described as the Golden Age of Latin literature. J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Gaius Maecenas, Augustus' chief diplomatic agent during the Civil War with Mark Antony and his confidante until his wife's brother was involved in a conspiracy (c. 22 B.C.), gathered about him a circle of poets, chief of them Virgil (Publius Virgilius Maro, 70–17 B.C.). Virgil first published the Eclogues, a collection of pastoral poetry, and then the Georgics, four well-crafted books on farming, and finally his great epic, the Aeneid, which became the national epic of the empire. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The chief archetypes of the Aeneid were the Iliad and the Odyssey attributed to Homer. The Aeneid told how Aeneas escaped the fall of Troy and wandered over the Mediterranean, visiting Carthage, where he had an ill-starred affair with the queen, Dido, and finally reaching Italy, where he had to fight to establish a settlement. It is a poem that celebrates Roman imperialism, but it is not without compassion for Rome's victims. Horace was five years Virgil's junior and the son of a freedman. Virgil introduced him to Maecenas, who gave him his Sabine farm, which Horace made famous in his poetry. He wrote odes, epistles, satires and a didactic poem on the art of poetry, but he declined to try an epic.

Ovid (43 B.C. to around A.D. 17) was an immensely talented and facile poet who wrote with wit and narrative skill and loved the fashionable society of Rome. His medley of myths of transformation called the Metamorphoses is his greatest work, but his Art of Love was his most notorious. For reasons that are unclear, in A.D. 8, Augustus banished him to Tomi on the Black Sea, where he spent the rest of his life. Livy (59 B.C.– A.D. 17) wrote an immense history of Rome which has partially survived. His style is mellifluent, but his accuracy is sometimes questionable.

The next generation produced authors such as Phaedrus (c. 15 B.C.– A.D. 50), who wrote a collection of fables in verse drawn from the Greek. Seneca the Younger (c. 4 B.C.– A.D. 65) was known chiefly as an essayist and playwright, Petronius (c. A.D. 20–66), the "Arbiter", socalled for having been the arbiter of taste for the emperor Nero, is the presumed author of a long picaresque novel, the Satyricon, which survives in fragments, the longest of which describes a banquet given by a rich freedman Trimalchio. Silius Italicus ( A.D. 26–101) wrote an epic in the Virgilian style, the Punica, which is about the Second Punic War, the war with Hannibal. Lucan (39–65), was the nephew of Seneca the Younger, and his Pharsalia on the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey is the greatest Latin epic after the Aeneid. Persius (34–62) is the author of a slim volume of six satires that strike a high moral tone, but his Latin is the language of the streets. Statius (c. 45–c. 96) is the author of the Thebaid, an epic on the myths of Thebes, and the Silvae, occasional poems, which were much admired in the Middle Ages but are little read now. Martial (c. 40–c. 104) is the most famous of all writers of epigrams, and his friend Juvenal (c. 60–c. 140) is the author of satires that comment bitterly on Roman life, though it is noticeable that his attacks are on people who were dead by the time he wrote. A writer's life was not without perils; both Seneca and Lucan killed themselves at Nero's command, and Petronius did likewise in anticipation of Nero's order.

The same period produced a clutch of notable writers in Latin prose. Little is known about Vitruvius, but his Ten Books on Architecture, which were written about 27 B.C., served the Renaissance as an invaluable textbook. Pliny the Elder (24–79) was the prefect of the Roman fleet at Misenum when Mt. Vesuvius erupted, and he died investigating it. He was a prolific author but only one work survives: his Natural History, a great treasury of interesting information in thirty-seven books. His nephew Pliny the Younger (61–114) left a panegyric on the emperor Trajan and ten books of carefully crafted letters.

Influence of Greek Literature and Philosophy on Roman Literature

According to Encyclopedia.com: The influence of Hellenism on Rome began in the 6th century B.C., but it became especially intense and all but over-whelming from the last half of the 3d century. A formal Latin literature was created under the direct influence of Greek models, and Latin antiquarians and poets connected Roman origins and Roman religion with Greek traditions and divinities as far as possible. Anthropomorphism now reached its full term, and Greek mythology was taken over by Latin writers and adapted to serve literary ends. The mythology of the Latin poets is simply Greek mythology in Latin dress. Aeneas the Trojan became the founder of Rome, and Caesar traced his ancestry back through Aeneas to Venus and Anchises. This religion of the poets reflects literary sophistication and convention rather than genuine belief, and it was so regarded by the small educated class for which it was written. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The rationalistic outlook of poets had its foundation in the rationalism of the Hellenistic Age as exemplified by Euhemerus, who was translated by Ennius, the father of Latin poetry. Under the impact of Hellenism, educated Romans became familiar not only with the older and contemporary Greek literature, but also with the various schools of Greek philosophy, especially with epicurean ism and stoicism, which were the most influential. While Epicureanism led to the repudiation of traditional religion as superstition, Stoicism gave an allegorical interpretation of the old myths, and its religiophilosophical teachings offered intellectuals an attractive and meaningful way of life. However, through Posidonius especially, Stoicism found a place for astrology and astral religion in its system. The typical rationalistic attitude of the educated Roman is well exemplified in the pertinent writings of Cicero and Varro.

Books and Libraries in Ancient Rome

Almost all the materials used by the ancients to receive writing were known to the Romans and used by them for one purpose or another, at different times. For the publication of works of literature, however, during the period when the great classics were produced, the only material was “paper” (papyrus), the only form the roll (volumen). The book of modern form (codex), written on parchment (membranum), played an important part in the preservation of the literature of Rome, but did not come into use for the purpose of publication until long after the canon of the classics had been completed and the great masters had passed away. The Romans adopted the papyrus roll from the Greeks; the Greeks had received it from the Egyptians. When the Egyptians first used it we do not know, but we have in museums Egyptian papyrus rolls that were written at least twenty-five hundred years before the Christian era. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The oldest Roman books of this sort that have been preserved were found in Herculaneum, badly charred and broken. Those that have been deciphered contain no Latin author of any value. At the time it was buried, there were still to be seen rolls in the handwriting of the Gracchi, and autograph copies of works of Cicero, Vergil, and Horace must have been common enough. All these have since perished, so far as we know.

“Libraries. The gathering of books in large private collections began to be general only toward the end of the Republic. Cicero had considerable libraries not only in his house at Rome, but also at his countryseats. Probably the bringing to Rome of whole libraries from the East and Greece by Lucullus and Sulla started the fashion of collecting books; at any rate collections were made by many persons who knew and cared nothing about the contents of the rolls, and every town house had its library lined with volumes. In these libraries were often displayed busts of great writers and statues of the Muses. Public libraries date from the time of Augustus. The first to be opened in Rome was founded by Asinius Pollio (died 4 A.D.), and was housed in the Atrium Libertatis. Augustus himself founded two others, and the number was brought up to twenty-eight by his successors. The most magnificent of these was the Bibliotheca Ulpia, founded by Trajan. Smaller cities had their libraries, too, and even the little town of Comum boasted one founded by Pliny the Younger and supported by an endowment that produced thirty thousand sesterces annually. The public baths often had libraries and reading-rooms attached to them.” |+|

Rise of Libraries and Publishing in Ancient Rome

Scholars and men of letters in Rome knew nothing for two centuries of what we mean by "publishing." Down to the end of the republic, they made copies of their works in their own houses or in the house of some patron, and then distributed the manuscripts to their friends. Atticus, to whom Cicero had entrusted his speeches and his treatises, had the inspiration of converting the copying studio he had set up for himself into a real industrial concern. At the same time Caesar, no less a revolutionary in things intellectual than in things material, helped to procure him a clientele by founding the first State Library in Rome, on the model of the great library which existed in the museum at Alexandria. The completion of the Roman library was due to Asinius Pollio, and it soon begot daughter libraries in the provinces. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The multiplication of public and municipal libraries resulted in the rise of publishers (bibliopolae, librarii). The new profession soon had its celebrities: the Sosii, of whom Horace speaks, who had opened a shop for volumina at the exit of the Vicus Tuscus on the Forum, near the statue of the god Vertumnus, behind the Temple of Castor; Dorus, to whom one went for copies of Cicero and Livy; Tryphon, who sold Quintilian's Institutio Oratorio, and Martial's Epigrams; and rivals of Tryphon Q. Pollius Valerianus; Secundus, not far from the Forum of Peace; and Atrectus in the Argiletum."

These book merchants, who assembled and trained teams of expert slaves, sold their copies dear enough 2 or 3 sesterces for a text which would correspond to about 20 pages of our duodecimo; 5 denarii or 20 sesterces for a liber, which would make somewhat less than 40 similar pages but had been elaborately gotten up. They were often paid by unknown writers for carrying out the work to order, but even in the case of famous authors they did not even buy the original manuscript which they condescended to "publish." They were also exempt from making any subsequent payment to the author for the jurists had vaguely extended to all writings on papyrus or on parchment the old legal principle that solo cedit superficies, that is to say, the ownership of every addition follows the ownership of the basis to which it is added. Thus the publishers grew rich by dispatching all over the world, "to the confines of Britain and the frosts of the Getae," the verses "which the centurion hummed in his distant garrison," but the poet's "money-bag knew nothing of it" as he starved in his poverty.

Manufacture of Papyrus and Rolls in Ancient Rome

a fragment of a Herculaneum scroll

The papyrus reed had a triangular stem which reached a maximum height of perhaps fourteen feet with a thickness of four or five inches. The stem contained a pith of which the paper made by a process substantially as follows. The stem was cut crosswise, and the rind removed. The pith was cut into thin lengthwise strips as evenly as possible. The first seems to have been made from one of the angles to the middle of the opposite side, and the others parallel with it to the right and to the left. The strips were then assorted according to width, and enough of them were arranged side by side as closely as possible upon a board to make their combined width almost equal to the length of the single strip. Across these was laid another layer at right angles, with perhaps a coating of glue or paste between them. The mat-like sheet that resulted was then soaked in water and pressed or hammered into a substance not unlike our paper, called by the Romans, charta. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“After the sheets (schedae) had been dried and bleached in the sun, they were freed of rough places by scraping and trimmed into uniform sizes, depending upon the length of the strips of pith. The fewer the strips that composed each sheet, or in other words the greater the width of each strip, the closer the texture of the charta and the better its quality. It was possible, therefore, to grade the paper by its size, and the width of the sheet rather than its height was taken as the standard. The best quality was sold in sheets about ten inches wide; the poorest that could be used to write upon came in sheets about six inches wide. The height in each case was perhaps one inch to two inches greater. It has been calculated that a single papyrus plant would make about twenty sheets, and this number seems to have been made the commercial unit of measure (scapus) by which the paper was sold, a unit corresponding roughly to our quire. |+|

“Making the Roll. A single sheet might serve for a letter or other brief document, but for literary purposes many sheets might be required. These were not fastened side by side in a back, as are the separate sheets in our books, or numbered and laid loosely together, as we arrange sheets in our letters and manuscripts, but, after the writing was done, they were glued together at the sides (not at the tops) into a long, unwieldy strip, with the lines on each sheet running parallel with the length of the strip, and with the writing on each sheet forming a column perpendicular the length of the strip. On each side of the sheet therefore, a margin was left as the writing was one, and these margins, overlapping and glued together, made a thick blank space, a double thickness of paper, between every two sheets in the strip. Very broad margins, too, were left at the top and bottom, where the paper would suffer from use a great deal more than in our books. When the sheets had been securely fastened together in the proper order, a thin slip of wood might be glued to the left (outer) margin of the first sheet, and a second slip (umbilicus) to the right (also outer) margin of the last sheet, much as a wall map is mounted today. When not in use, the volume was kept tightly rolled about the umbilicus. Some authorities think that the umbilici were not always attached to the rolls, but that they might be slipped in when the books were in use.2

“A roll intended for permanent preservation was always finished with greatest care. The top and bottom (frontes) were trimmed perfectly smooth, polished with pumice-stone, and often painted black. The back of the roll was rubbed with cedar oil to defend it from moths and mice. To the ends of the umbilicus were added knobs (cornua), sometimes gilded or painted a bright color. The first sheet would be used for the dedication, if there was one, and on the back of it were frequently written a few words giving a clue to the contents of the roll; sometimes a pen-and-ink portrait of the author graced this page. In many books the full title and the name of the author were written only at the end of the roll on the last sheet, but in any case to the top this sheet was glued a strip of parchment (titulus) with the title and author’s name upon it; the strip projected above the edge of the roll. For every roll a parchment cover was made, cylindrical in form, into which it was slipped from the top; the titulus alone was visible. If a work was divided into several volumes, the rolls were put together in a bundle (fascis) an kept in a wooden box (capsa, scrinium) like a modern hat box. When the cover was removed, the tituli were visible, and the roll desired could be taken without disturbing the others. The rolls were kept sometimes in cupboards (armaria), where they were laid lengthwise on the shelves with the tituli to the front, as shown in the figure in the next paragraph. |+|

Herculaneum scroll today

“Size of the Rolls. When a volume was consulted, the roll was held in both hands and unrolled column by column with the right hand, while with the left the reader rolled up the part he had read on the slip of wood fastened to the margin of the first sheet, or around the umbilicus. When he had finished reading, he rolled the volume back upon the umbilicus, usually holding it under his chin and turning the cornua with both hands. In the case of a long roll this turning backward and forward took much time and patience and must have sadly soiled and damaged the roll itself. The early rolls were always long and heavy. There was theoretically no limit to the number of sheets that might be glued together, and consequently none to the size or length of the roll. It was made as long as was necessary to contain the given work. In ancient Egypt rolls were put together of more than fifty yards in length, and in early times rolls of corresponding length were used in Greece and Rome. From the third century B.C., however, it had become customary to divide works of great length into two or more volumes. The division at first was purely arbitrary and made wherever it was convenient to end the roll, no matter how much the unity of thought was interrupted. A century later authors had begun to divide their works into convenient parts, each part having a unity of its own, such as the five “books” of Cicero’s De Finibus, and to each of these parts, or “books,” a separate roll was allotted. An innovation so convenient and sensible quickly became the universal rule. It even worked backward; some ancient works, which had not been divided by their authors, e.g., Herodotus, Thucydides, and Naevius, were now divided into books. About the same time, too, it became the custom to put upon the market the sheets already glued together, to the amount at least of the scapus. It was, of course; much easier to glue two or three of these together, or to cut off the unused part of one, than to work with the separate sheets. The ready-made rolls, moreover, were put together in a most workmanlike manner. Even sheets of the same quality would vary slightly in toughness or finish, and the manufacturers of the roll were careful to put the very best sheets at the beginning, where the wear was the most severe, and to keep for the end the less perfect sheets, which might sometimes be cut off altogether.” |+|

Publications of Books in Ancient Rome

Multiplication of Books. The process of publishing the largest book at Rome differed in no important respect from that of writing the shortest letter. Every copy was made by itself, the hundredth or the thousandth taking just as much time and labor as the first had done. The author’s copy would be distributed for reproduction among a number of librarii, his own, if he were a man of wealth, a Caesar or a Sallust; his patron’s, if he were a poor man, a Terence or a Vergil. Each of the librarii would write and rewrite the portions assigned to him, until the required number of copies had been made. The sheets were then arranged in the proper order, if the ready-made rolls were not used, and the rolls were mounted as has been described. Finally the books had to be looked through to correct the errors that were sure to be made, a process much more tedious than the modern proofreading, because every copy had to be corrected separately, as no two copies would show precisely the same errors. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Books made in this way were almost exclusively for gifts, though friends would exchange books with friends and a few might find their way into the market. Up to the last century of the Republic there was no organized book trade, and no such thing as commercial publication. When a man wanted a book, instead of buying it at a bookstore he borrowed a copy from a friend and had his librarii make him as many more as he desired. In this way Atticus made for himself and Cicero copies of all the Greek and Latin books on which he could lay his hands, and distributed Cicero’s own writings everywhere. |+|

“Commercial Publication. The publication of books at Rome as a business began in the time of Cicero. There was no copyright law and no protection therefore for author or publisher. The author’s pecuniary returns came in the form of gifts or grants from those whose favor he had won by his genius; the publisher depended, in the case of new books, upon meeting the demand before his rivals could market their editions, and, in the case of standard books, upon the accuracy, elegance, and cheapness of his copies. The process of commercial publication was essentially the same as the method already described, except that larger numbers of librarii would be employed. The publisher would estimate as closely as possible the demand for any new work that he had secured, would put as large a number of scribes upon it as possible, and would take care that no copies should leave his establishment until his whole edition was ready. After the copies were once on sale, they could be reproduced by anyone. The best houses took all possible pains to have their books free from errors; they had competent correctors to read them copy by copy, but in spite of their efforts blunders were legion. Authors sometimes corrected with their own hands the copies intended for their friends. In the case of standard works purchasers often hired scholars of reputation to revise their copies for them, and copies of known excellence were borrowed or hired at high prices for the purpose of comparison. |+|

“Rapidity and Cost of Publication. Cicero tells us of Roman senators who wrote fast enough to take evidence verbatim, and the trained scribes must have far surpassed them in speed. Martial tells us that his second book could be copied in an hour. It contains five hundred and forty verses, which would make the scribe equal to nine verses to the minute. It is evident that a small edition, consisting of copies not more than twice or three times as numerous as the scribes, could be put upon the market more quickly than it could be produced now. |+|

The cost of the books varied, of course, with their size and the style of their mounting. Martial’s first book, containing eight hundred twenty lines and covering thirty-nine pages in Teubner’s text, sold at thirty cents, fifty cents, and one dollar; his Xenia, containing two hundred and seventy-four verses and covering fourteen pages in Teubner’s text, sold at twenty cents, but cost the publisher less than ten. Such prices would hardly be considered excessive now. Much would depend upon the reputation of the author and the consequent demand. High prices were put on certain books. Autograph copies—Gellius (late in the second century, A.D.) says that one by Vergil cost the owner one hundred dollars—and copies whose correctness was vouched for by some recognized authority commanded extraordinary prices.” |+|

Reading Scrolls

Mary Beard, a professor of classics at Cambridge University, wrote in the New York Times: The books Greeks and Romans read “were not “books” in our sense but, at least up to the second century. The “book rolls” — long strips of papyrus, rolled up on two wooden rods at either end. To read the work in question, you unrolled the papyrus from the left-hand rod, to the right, leaving a “page” stretched between the two. It was considered the height of bad manners to leave the text on the right hand rod when you had finished reading, so that the next reader had to rewind back to the beginning to find the title page, bad manners — but a common fault, no doubt, Some scribes helpfully repeated the title of the books a the very end, with just this problem in mind.”

“These cumbersome rolls made reading a very different experience than it is with the modern book,” Beard wrote. “Skimming, for example, was much more difficult, as looking back a few pages to check out the name you had forgotten (as it is on Kindle). Not to mention the fact that at some periods of Roman history, it was fashionable to copy a the text with no breaks between words, but as a river of letters. In comparison, deciphering the most challenging postmodern text (or “Finnegan’s Wake,” for that matter) looks easy.”

Ancient Roman Book Market

Julius Caesar was a writer... Beard wrote in the New York Times: “All reading material was laboriously copied by hand. The ancient equivalent of the printing press was a battalion of slaves whose job it was to transcribe one by one as many copies of Virgil. Horace or Ovid as the Roman market would buy.”

“Bookstores in Rome clustered in particular streets . One was she Vicus Sandalarius, or Shoemaker’s Row, not far from the Colosseum (convenient for post-gladiatorial browsing). Here you would find the outsides of the stores plastered with advertisements and puffs for titles in stock, often adorned with some choice quotes from the books of the moment. Martial, in fact, once told a friend not to bother to venture inside, since you could “read all the poets” on their door posts.

For those who did go in, there was usually a place to sit and read. With slaves on hand to summon up refreshments, it would have been not unlike the coffee shop in a modern Borders. For collectors there were occasionally secondhand treasures to be picked dup at a price. One Roman academic reported finding an old copy of the second book of Virgil’s “Aeneid” — not just any old copy but, the bookseller assured him, Virgil’s very own.”

A new book could cost as much as two years of salary for a professional soldier, “The risks on cheaper purchases were different.” Beard wrote, “A cut price book roll would presumably have fallen to pieces as quickly as a modern mass-market paperback. But worse, the pressure to get copies made quickly meant they were loaded with errors and sometimes uncomfortably different from the authentic words of the author, One list of prices from the third century A.D. implies that the money needed to buy a top-quality copy of 500 lines would be enough to feed a family for four (admittedly on very basic ration) for a whole year.

Public Readings in Ancient Rome

The habit in ancient Rome of giving and hearing public readings and recitations was an absorbing occupation and perpetual distraction of cultivated Romans and grew as a result of the publishing business described above, where it was inevitable that literary beginners and impecunious authors should seize the opportunity given by a public recitation of their prose or of their poems either to escape the demands of the librarius or to force his hand. They had no hesitation in thus deflowering a subsequent edition which would never bring them in a penny. It was also natural that the imperial government, which hoped to control literary production but shrank from the scandal caused by the autos-da-fe decreed by Tiberius, or the death sentence which Domitian had pronounced against Hermogenes of Tarsus and his publishers, preferred to arrive unobtrusively at the same result by underground methods which had proved effective in the valley of the Nile. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The prefects and procurators placed in charge of the public libraries already possessed the power to effect the slow but certain disappearance of dangerous or suspect books to which they had closed the doors of their bookcases. They claimed the right to sow the good seed of writings favorable to the regime and compositions useful as propaganda. We need, therefore, feel no surprise if Asinius Pollio, who gave his name to the first library in Rome, was the first to recite his works before his friends. This practice was too well suited to the condition of writers and the desires of government not to become the fashion quickly. Thus the conjunction of omnipotent publishers and servile libraries gave birth to a monster, the public recitatio, which soon grew to be the curse of literature. The calculations of the politicians and the vanity of authors set the fashion. After that nothing could stop it.

...So was Emperor

Marcus Aurelius From the very beginning of his reign, Augustus' enthusiasm for recitations helped their progress; he would listen "with as much goodwill as endurance to those who read aloud to him not only verses or history but also speeches and dialogues." A few years later things had gone even further. Claudius, who at Livy's instigation had started to write history, delighted to declaim his chapters one by one as he finished them. Since he was of the blood royal, he had no difficulty in getting a full house. But he was shy and a stammerer, and at one of his experimental readings a grotesque incident occurred a bench collapsed under the weight of a fat member of the audience, provoking volleys of laughter that were not on the agenda. After this he gave up reading aloud himself. But he did not abandon the pleasure of hearing his lucubrations declaimed in the cultured, voice of a freedman. Later, when he became emperor, he put his palace at the disposal of others for their readings, and was only too happy if he could find leisure to be present as an ordinary listener. He would suddenly appear among an audience startled at this unexpected honor, a trick he played one day on the ex-consul Nonianus. Domitian in his turn affected a passionate love of poetry and on more than one occasion himself read his own verses in public. It is probable that Hadrian followed suit; at least he set his seal on public readings by consecrating a building for this exclusive purpose: the Athenaeum, a sort of miniature theater, which he had built with his own money on a site which is unknown to us.

The building of the Athenaeum was merely an indication of the importance public readings had acquired in the Urbs, which was now submerged under a flood of talent. There was nothing new about its architecture ; it simply added an official monument to the numerous other halls which had long been filled with the eloquent murmur of these recitals. Any well-educated man who was moderately well off cherished the ambition of having a room in his house, the auditorium, especially for readings. More than one friend of Pliny the Younger embarked light-heartedly on this considerable expense Calpurnius Piso, for instance, and Titinius Capito. The plan of these auditoria varied little from house to house: a dais on which the author-reader would take his seat after having attended to his toilet, smoothed his hair, put on a new toga, and adorned his fingers with all his rings for the occasion. He was then prepared to entrance his audience not only with the merit of his writing but by the distinction of his presence, the caress of his glances, the modesty of his speech, and the gentleness of his modulations. Behind him hung the curtains which hid those of his guests who wished to hear him without being seen, his wife for example. In front of the reader the public who had been summoned by notes delivered at their homes (codicilli) were accommodated, in armchairs (cathedrae) for people of the higher ranks and benches for the others. Attendants told off for the purpose distributed the programs of the seance (libelli).

Ancient Roman Writers

The late 1st century B.C. and the first century A.D. was the Golden Age of Roman literature. Great Roman famous poets included the naughty Catuluus, the romantics Tibullus and Propertius, the epic-maker Virgil and the love scribe Ovid. The great historians and rhetoricians include Horace, Livy, Cicero and Caesar from the later Republican period and Petronius and Seneca from the early Imperial period.

Writers were not very well paid and had a hard time making money from their work. Casson wrote that one dramatist “made his living by selling scripts, and they did not make him rich; indeed at times he was penniless. It was written that three plays of his were written in his spare time from a job turning a millstone.”

Writers received a lump sum from a book seller for the rights to copy his works. Once a text hit the streets there was no way to prevent pirated copies. One writer lamented, “My book is thumbed by our soldiers posted overseas, and even in Britain people quote my words. What’s the point? I don’t make a penny from it.” Other writers compared their job to that of prostitutes and called their publishers pimps. The Emperor Augustus once referred to a slim book of poetry he wrote as being “on the game, all tarted up with the cosmetics of Sosius & Co.”

Writers like Horace that seemed to have done well for themselves did so because they were taken under the wing of a patron. Horace was put up in a house by Maecenas, Augustus’s unofficial minister of culture. Others had to work hard to plug their work. In the early 2nd century A.D. Pliny complained that in Rome, “There was scarcely a day in April when someone wasn’t giving a reading.” And the poor authors had to put up with small audiences, most of whom slipped out before the reading was over.

Lost Classics

scene from the Plautus play Cistellaria

John Seabrook wrote in The New Yorker: “One could dare hope for one or two of the lost histories of Livy, of whose hundred and forty-two books on the history of Rome only thirty-five survive. Or perhaps one of the nine volumes of verse written by Sappho, the Greek poet; only one complete poem remains. By some estimates, ninety-nine per cent of ancient Greek literature has been lost, and Latin has not fared much better. [Source: John Seabrook, The New Yorker , November 16, 2015 \=/]

“Among those works we know are missing are Aristotle’s second volume of the Poetics, which was on comedy; Gorgias’ philosophical work “On Non-Existence”; the four missing books of the Roman historian Tacitus’ Annals, covering Caligula’s reign and the beginning of Claudius’; Ovid’s version of “Medea”; and Suetonius on the Greek athletic games. (His “Lives of Famous Whores” also, sadly, has not survived.) Greek tragedy has been decimated. According to the Suda, the tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia of classical culture, Euripides wrote as many as ninety-two plays; eighteen survive. \=/

“We have seven each from Aeschylus and Sophocles, who wrote about ninety and a hundred and twenty, respectively. “And that’s just the big three of tragedy,” the writer and classics professor Daniel Mendelsohn told me. “Of the thousand that were likely written and performed during the hundred-year heyday of tragedy, we have only thirty-three extant plays—that’s about a three-per-cent survival rate.” \=/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024