Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

LOOKS-OBSESSED ROMANS

Caracalla

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The ancient Greeks and Romans were somewhat looks-obsessed: they provide us with wildly racist handbooks that use bodily characteristics to determine and dissect a person’s character. According to these and broader consensus, you could tell the kind of person you were dealing with from their appearance. The Roman Emperor Augustus is described by his biographer Suetonius as “unusually handsome” even though “he cared nothing for personal adornment” and his eyes were so clear and bright it was almost as if they had a certain divine power. The Emperor Otho, who ruled for a mere handful of months, was less fortunate. Suetonius pictures him as unmanly and effeminate: he was “splay-footed and bandy-legged,” wore wigs to conceal his receding hairline, and spent a lot of his time depilating his body and admiring himself in a mirror.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 15, 2020]

Descriptions of a person’s physical appearance could go far beyond just the color of their hair, eyes, and skin. Everything from the tenor of a person’s voice to the way that they carried themselves was up for debate. Plutarch tells us about how Alexander the Great smelled: he had a “very pleasant odour [that] exhaled from his skin” and filled his garments. In a world without deodorant this is quite an advantage. A description of a self-emancipated third century slave refers to both his honey-colored skin and the fact that he walks around like a bigshot “yapping in a shrill voice.”

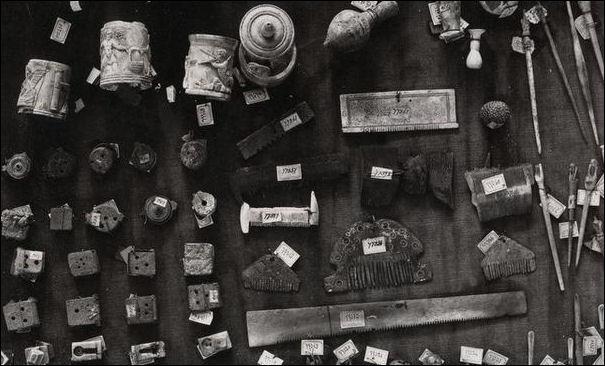

A glass dish, slate makeup palette, silver hand mirror, folding knife, necklace and earrings were found in a Roman grave in Germany. According to Archaeology magazine:It was common in antiquity for deceased individuals to be sent on their journey to the afterlife with a collection of their cherished objects. Nevertheless, archaeologists in Germany were surprised by the burial assemblage of a wealthy Roman woman who was entombed with her jewelry, her makeup kit, and other finely crafted beauty items. “Cosmetic utensils and jewelry as gifts in women’s graves are not uncommon, but the variety and quality of the offerings is particularly interesting,” says Susanne Willer of the LVR-LandesMuseum in Bonn. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2018]

“The discovery was made during the installation of sewer and drainage systems near Zülpich. The 25-to-30-year-old woman died around the fourth century A.D. and was interred in a massive stone sarcophagus. When researchers finally lifted and opened the 4.5-ton casket, they discovered a wealth of well-preserved cosmetic artifacts, including glass perfume vials, a bronze oil jar, a silver hand mirror, and a slate makeup palette, with application tools, hairpins, and even a finely carved folding knife with a Hercules figurine as its handle. One glass jar contained the Latin phrase Utere Felix, meaning “use (this) and be happy.” The unknown woman was buried along what would have been the main road connecting the important Roman towns of Trier and Cologne. “These burial offerings,” says Willer, “highlight the life of the rural upper classes in the Rhineland 1,700 years ago, their everyday culture, and their luxury.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

HAIR IN ANCIENT ROME: STYLES, BEARDS, SHAVING, BARBERS, SLAVE STYLISTS europe.factsanddetails.com

CLOTHES-MAKING IN ANCIENT ROMAN: FABRICS, WEAVING, COLORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN CLOTHES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN FOOTWEAR AND HATS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JEWELRY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cosmetics & Perfumes in the Roman World” by Susan Stewart (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pearls and Petals Beauty Rituals in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Jewellery” by Filippo Coarelli (1970) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity”| by Mary Harlow (2022) Amazon.com;

“Hair-Dressing of Roman Ladies as Illustrated on Coins”

by Maria Millington Evans (1994) Amazon.com;

“Hair: A Biblical and Scholarly Perspective for Christian Women”

by Eugene Dominguez and Sherri Dominguez (2020) Amazon.com;

“The World of Roman Costume” by Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante (2001) Amazon.com;

“Roman Clothing and Fashion” by Alexandra Croom (2012) Amazon.com;

“Roman Women’s Dress: Literary Sources, Terminology, and Historical Development”

by Jan Radicke, Joachim Raeder (2022) Amazon.com;

“Masculinity and Dress in Roman Antiquity” (Routledge) by Kelly Olson (2017) Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume I: Books 1–4" (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. On Exercise with a Small Ball (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Bathing in the Roman World” by Fikret Yegül Amazon.com;

“Bathing in Public in the Roman World” by Garret Fagan.(1999) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Bathing in Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium”

Amazon.com;

“The Essential Roman Baths” by Stephen Bird (2007) Amazon.com;

"Roman Bath” by Peter Davebport (2021) Amazon.com;

“Baths of Caracalla: Guide” by Gail Swirling (2008) Amazon.com;

“Decoration and Display in Rome's Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla” by Maryl B. Gensheimer (2018) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Pale Skin Ancient Greece and Rome

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Tanning as a practice is a relatively new arrival to the beauty scene; until the nineteenth century pallor was the skin tone of choice. And people employed a whole host of dangerous beauty treatments in order to achieve it. For the ancient Greeks and Romans a pale complexion was deemed the most desirable. Roman love poetry extols the merits of the radiantly white girl and Greek mythology admires the pale-armed heroines and goddesses like Andromache and Hera. Paleness was seen as a marker of beauty but also, for some, as an indication of character. Aristotle’s Physiognomy relates that “a vivid complexion shows heat and warm blood, but a pink-and-white complexion proves a good disposition.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, September 4, 2016]

cosmetics with an Aphrodite statue

More than character, however, pale skin was a marker of social status and class. It was a sign that women (and men) did not have to engage in the kind of menial work that would take them outside into the sun. In women paleness had a kind of moral dimension: it was a sign that a woman had remained in the household and, as Caesar might put it, was “above reproach.”

The preoccupation with pale radiant beauty even had a religious dimension. Sixth-century mosaics from a church in Ravenna, Italy, depict a procession of male and female saints in heaven as pale, aristocratic, Roman Stepford Wife-like figures, in near-identical attire. The only way to identify the saints is by the names above their heads. The mosaics are illustrative of the Greco-Roman preoccupation with uniformity, but, as I have argued in an academic article, they are also an act of what we might call ancient whitewashing: They impose Roman beauty standards on North African saints.

Paleness, of course, is relative. Life in southern Italy and Greece does not lend itself to pallor and, thus, Roman aristocrats turned to cosmetics: predominantly chalk but sometimes also lead to whiten their faces. They weren’t alone. Their medieval counterparts used lotions made of violet and rose oil to protect their skin from the sun. It’s difficult to imagine these sunscreens were effective but, then again, many modern sunscreens also fall short.

Beauty Aids in Ancient Rome

Roman women had a great love of makeup and jewelry. Following their baths, women might use different types of skin cream, perfumed oils, and makeup. According to Encyclopedia.com: Their makeup was made from foul-smelling ingredients such as milk and animal fat, and perhaps they wore strong perfumes to mask the odor. Roman women also applied beauty spots, or colored patches, to their faces. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

In inventories of female inheritance, the personal objects which a woman left behind her were legally divided into three categories; toilet articles (mundus muliebris) adornments (ornamenta), and clothes (vestis). Under the heading vestis the lawyers enumerate the different garments which women wore. To the toilet belonged everything she used for keeping clean (mundus muliebris est quo mutter mundior fit): her wash-basins (matellae), her mirrors (specula) of copper, silver, sometimes even of glass backed not with mercury but with lead; and also, when she was fortunate enough to be able to disdain the hospitality of the public bath, her bathtub (lavatio). [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Her "adornments" included the instruments and products which contributed to her beautification, from her combs and pins and brooches (fibulae) to the unguents she applied to her skin and the jewels with which she adorned herself. At bathing time her mundus and her ornamenta were both needed ; but when she first got up in the morning it was enough for her to "adorn" herself without washing: "ex somno statim ornata non commundata"

The Greeks had schools for mirror making, where students were taught the finer points of sand polishing. Romans preferred mirrors made from silver because they revealed the true colors of facial make up. Archaeology magazine reported: Five lead mirror frames dating to the turn of the third century A.D. have been found in a square building at a Roman villa outside the town of Pavlikeni in northern Bulgaria. Three of the frames are decorated with the image of a large wine vessel and bear an inscription that means a “good soul.” The villa belonged to a Roman military veteran and was built around the turn of the second century A.D. The building where the frames were found was thought to have housed villa workers. But, says excavation leader Karin Chakarov of the Pavlikeni Museum of History, the presence of the mirror frames suggests it may instead have been a temple. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2018]

Cosmetics in Ancient Rome

Roman pyxis, cosmetics jar

Like the Egyptians but unlike the Greeks, Romans were very fond of cosmetics and perfumes. The poet Lucian once wrote: "If you could see women when they wake up in the morning, you would think them less desirable than an ape. That is why they keep themselves closeted and will not show themselves to a man. Old hags and a chorus of sitting maids, no more glamorous than their mistress, surround her, plastering her wretched face with a variety of remedies...Countless concoctions are used...salves for improving her unpleasant complexion...jars full of mischief, tooth powders and stuff for darkening the eyelids." Women's toiletry articles included spatula for applying cosmetics, combs, scent bottles with perfume and a cosmetic box. One of the most common ways of lightening the skin was applying powdered lead. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum ||]

Cosmetics ranged from home-made concoctions to sophisticated mixtures, Cosmetics and perfumes were usually oil based. The distillation of alcohol had not been invented. Cosmetics were kept in elaborate make-up cases or glass or alabaster bottles. According to Archaeology magazine:Like many people today, the Romans used makeup to reduce visible signs of aging and achieve glowing skin. High-end products, such as costly saffron eye shadow, were targeted to a wealthy clientele.

Roman soldiers used Indian perfumes, cosmetics, nail lacquers, and lightened their hair with a mixture of yellow flour, pollen and gold powder. Roman military leaders used to have their hair curled and lacquered, and lips and nails painted before battles. Pliny recommended using ass's milk to remove wrinkles and a mixture of mouse droppings, wine , saffron, pepper and vinegar as a remedy for thinning hair.

Romans used foundation creams, astringents, creams, eye shadows, eye liners, lipstick, toothpaste, whiteners, hair tints and dyes. It is believed that Roman women had access to almost every kind of make-up used by modern women. One Roman wrote her friend: "While you remain at home, Galla, your hair is at the hairdressers; you take your teeth out at night and sleep tucked away in a hundred cosmetic boxes — even your face does not sleep with you. Then you wink at men under an eyebrow you took out of a drawer that same morning."

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “The gladiators who lost became medicine for epileptics while the winners became aphrodisiacs. In Roman times, soap was hard to come by, so athletes cleaned themselves by covering their bodies in oil and scraping the dead skin cells off with a tool called a strigil. “Usually, the dead skin cells were just discarded—but not if you were a gladiator. Their sweat and skin scrapings were put into a bottle and sold to women as an aphrodisiac. Often, this was worked into a facial cream. Women would rub the cream all over their faces, hoping the dead skin cells of a gladiator would make them irresistible to men.”[Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

Ingredients of Ancient Roman Beauty Aids — Blood, Fruit, Milk and Semen

In ancient times and today, there has been a belief that blood contains the power to preserve youth and beauty. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Ancient medics claimed that the blood of gladiators and virgins had special medicinal properties. Milk was an apparent mainstay of the ancient Egyptian toilette. According to legend, Cleopatra used the milk of seven hundred donkeys in the place of bath water. The regime seems to have worked, as she managed to bed both Julius Caesar and Marc Anthony and was described by Cassius Dio as “a woman of surpassing beauty” who was “brilliant to look on.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

Dr. Jessica Baron, a historian of science, told The Daily Beast that Roman women thought milk from an ass (the animal) would whiten their skin and make it softer. In ancient thought milk was connected to birth, new life, and sustenance and, thus, was a good tool for preserving one’s youth. Modern scientists, on the other hand, would identify the lactic acid in milk as an (admittedly mild) exfoliant, which can perhaps explain the brilliance of Cleopatra’s skin. If you were trying to recreate this at home you should be sure to include honey and rose petals in the mix. Cleopatra, like many ancient Greek women, would use rose water as a kind of hydrator. To this day there are all kinds of beauty products that rely upon the hydrating effects of milk and roses.

A number of ancient Greek and Roman medics hypothesized that semen was concentrated blood, making it an especially potent emission for the preservation of life. If a young woman did not have sex at all she was liable to suffer from a disease called, somewhat self-explanatorily, the Disease of the Virgins. Fruit was an ancient and effective tool in the pursuit of eternal youth. The Romans thought that strawberries could be used to cure all kinds of medical symptoms, from halitosis to fevers to diseases of the blood. And Dioscordes’ first century A.D. De Materia Medica gives all kinds of advice on fruit, seeds, tree leaves, roots in youth-preserving skincare. Galen recommends that you drink red wine to heat the blood, preserve youthfulness, and most importantly, increase your virility and sexual performance. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

Roman toiletry items

Roman-Era Facial Cream

A fair complexion was fashionable and women used various kinds of cosmetics to make their skin white. Some women whitened their faces, bosoms and necks with a white powder made from lead. Greeks and Romans used arsenic as a depilatory to remove hair.

An ancient Roman cosmetics cream was found in a tin canister in a A.D. 2nd century site near London. Thought to be some kind of foundation, the cream consisted of about 40 percent animal fat (most likely from sheep or cattle) and 40 percent starch and tin oxide. The fat made the cream creamy and the tin oxide made it white. Richard Evershed, a chemist at the University of Bristol, who studied it, told Reuters, “It is quite a complicated little mixture. Perhaps they didn't understand the chemistry but they obviously knew what they were doing...As far as I can tell , the tin oxide was quite inert so it wouldn't cause any dermatological problems."

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Discovery News: “The world's oldest cosmetic face cream, complete with the finger marks of its last user 2,000 years ago were found by archaeologists excavating a Roman temple on the banks of London's River Thames. Measuring six by five centimeters the tightly sealed, cylindrical tin can contained a pungent-smelling white cream. "It seems to be very much like an ointment, and it's got finger marks in the lid ... whoever used it last has applied it to something with their fingers and used the lid as a dish to take the ointment out," Museum of London curator Liz Barham said as she opened the box. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery News, July 30, 2003]

“The superbly made canister, now on display at the museum, was made almost entirely of tin, a precious metal at that time. Perhaps a beauty treatment for a fashionable Roman lady or even a face paint used in temple ritual...We don't yet know whether the cream was medicinal, cosmetic or entirely ritualistic. We're lucky in London to have a marshy site where the contents of this completely sealed box must have been preserved very quickly - the metal is hardly corroded at all," said Nansi Rosenberg, a senior archaeological consultant on the project. "This is an extraordinary discovery," Federico Nappo, an expert on ancient Roman cosmetics of Pompeii. "It is likely that the cream contains animal fats. We know that the Romans used donkey's milk as a treatment for the skin. "

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: Chemical analysis of the substance revealed its three primary surviving components, allowing researchers to re-create the cream. Animal fat gave the concoction an oily texture that moisturized the skin, explains Museum of London curator Francis Grew, while starch produced a powdery sheen. The third component, however, was entirely unexpected — tin, a metal that no written source lists as an ingredient of Roman cosmetics. Rather than lead-based whiteners that were normally used in Roman makeup, the creators of this product used tin, which would have produced a similarly fair tone. “For women in Roman society, a white complexion signified that they didn’t go outdoors or do hard work, and that they had servants who attended to their needs,” Grew says. “Considering the possible ritual importance of this ditch, could it be that this was some sort of offering to the god by way of thanks for the remarkable properties of this cream?” [Source Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2021]

Ancient Roman Tattoos

In the Roman Empire, tattoos were associated with slavery. Slaves were marked to show their taxes had been paid. The emperor Caligula tattooed gladiators — as public property — and early Christians condemned to the mines. According to Archaeology magazine: Many of the ancient cultures the Romans encountered — Thracians, Scythians, Dacians, Gauls, Picts, Celts, and Britons, to name a few — tattoos were seen as marks of pride. Herodotus tells us that for the Thracians, tattoos were greatly admired and “tattooing among them marks noble birth, and the want of it low birth.” [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2013]

Persians, Greeks, Romans, Scythians, Dacians, Gauls, Picts, Celts and Britons all had tattoos. An inscription from Ephesus details how all slaves imported from Asia were tattooed with the words "tax paid." Acronyms, words and sentences were tattooed or even gouged on the foreheads, necks, arms, and legs of slaves and convicts. "Stop me, I am a runaway slave" was commonly written across the foreheads of Roman slaves.

Caligula "defaced many people of the better sort" with tattoos that condemned them to slavery. Gladiators were tattooed as public property and soldiers were sometimes tattooed to keep them from deserting. Christians sometimes received forehead tattoos and were condemned to work in mines.

Constantine finally outlawed the practice of facial tattoos of convicts, gladiators and soldiers because the human face reflected, he said "the image of divine beauty. It should not be defiled."

Roman doctors developed methods for removing tattoos that were painful and risky. The Roman doctor Aettius wrote, "Clean the tattoo with niter, smear with resin of terebinth and bandage for five days." On the sixth day "prick the tattoo with a sharp pin, sponge away the blood, and cover with salt. After strenuous running to work up a sweat, apply caustic poultice, the tattoo should disappear in 20 days." The caustic preparations wiped out the tattoo by ulcerating the skin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024