Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

PERSONAL HYGIENE AND CLEANLINESS IN ANCIENT ROME

Roman men that could bathed daily. That was their main form of body care and adornment aside from perhaps wearing a signet ring. Women also bathed frequently and upper class one sometimes took great care and time to prepare their hair and adorn themselvess. In Roman times, people generally didn't use soap, they cleaned themselves with olive oil and a scraping tool. A wet sponge placed on a stick was used instead of toilet paper.

Roman attitudes toward hygiene and cleanliness changed over time. According to Encyclopedia.com: From the serious and simple habits of the eighth-century-B.C. founders of the city of Rome, Romans became increasingly concerned with bathing, jewelry, and makeup. By the time of the Roman Empire, bathing had become an elaborate public ritual, wealthy Romans imported precious jewels from throughout their vast empire, and women wore complicated cosmetics. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The ancient Roman breakfast often consisted of a glass of water swallowed in haste. They did not waste time in washing for they knew they would be going to bathe at the end of the afternoon, either in their private balneum if they were rich enough to have had one installed in their own house, or else in one of the public thermae. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Romans used the dirty oil from men’s bodies collected at baths for women's conditioner, and urine in Rome was used to whiten teeth. While recipes for soap date back to the ancient Babylonians, Romans didn't use it much. Instead, researchers at the University of Chicago say Romans used to mix water and urine to wash their clothes and brush their teeth that was collected from large vessels on the street set out for people to urinate into. and fill.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME: DISGUSTING PUBLIC ONES, CHAMBER POTS AND TAXES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATHING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATHS IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS factsanddetails.com

BEAUTY AND COSMETICS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Pollution and Religion in Ancient Rome” by Jack J. Lennon (2013) Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume I: Books 1–4" (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. On Exercise with a Small Ball (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Cosmetics & Perfumes in the Roman World” by Susan Stewart (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pearls and Petals Beauty Rituals in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems”

by Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow (2018) Amazon.com;

“Public Toilets (Foricae) and Sanitation in the Ancient Roman World: Case Studies in Greece and North Africa” by Antonella Patricia Merletto (2023) Amazon.com;

“Latrinae et Foricae: Toilets in the Roman World”, Illustrated, by Barry Hobson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Bathing in the Roman World” by Fikret Yegül Amazon.com;

“Bathing in Public in the Roman World” by Garret Fagan.(1999) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Bathing in Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium”

Amazon.com;

“The Essential Roman Baths” by Stephen Bird (2007) Amazon.com;

"Roman Bath” by Peter Davebport (2021) Amazon.com;

“Baths of Caracalla: Guide” by Gail Swirling (2008) Amazon.com;

“Decoration and Display in Rome's Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla” by Maryl B. Gensheimer (2018) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Grooming Habits and Tools of Ancient Romans

Becky Little wrote in National Geographic: More than 50 tweezers and a nail cleaner are among the artifacts that archaeologists have unearthed in Britain dating back to when it was part of the Roman Empire. One of the Romans’ most notable cultural exports were their bathhouses and grooming habits, which spread throughout the Roman Empire’s other conquered territories, too. “It is these enormous municipal public baths that take these practices with them as they spread across the empire,” says Cameron Moffett, a curator at English Heritage. Tweezers, which Romans used to pluck unwanted body hair, “didn’t exist in Britain before the Romans arrived.” Once the Romans invaded Britain, tweezers seemed to abound. These and other artifacts offer a painful peek into how Roman grooming tools and habits spread with the expansion of the Roman Empire after its founding in 27 B.C.[Source Becky Little, National Geographic, July 2, 2024]

Nail Care: Romans could clean and trim their nails (or have someone do this for them) at home, at the public baths, or—if they were men—at a barbershop. The Roman poet Horace, who lived during the first century B.C., wrote a line about “A close-shaven man, it’s said, in an empty barber’s / Booth, penknife in hand, quietly cleaning his nails.”

People in the city of Rome likely used knives or shears to tend to their nails, Moffett says. But interestingly, the nail cleaner unearthed in Gloucestershire that Oxford Cotswold Archaeology announced finding in May 2024 “is quite specific to this part of Britain,” says Alex Thomson, a project manager for the organization. This type of V-shaped nail cleaner (which could also serve as a file) only appears at Roman-era sites in Britain. “No one knows quite why,” Moffett says, “but it was something that was developed in Britain, and so you simply do not get them on the continent.”

Body Hair Removal: One of the personal grooming fads in Rome during the empire, at least among wealthy elites, was body hair removal. Both men and women might pluck out their own unwanted hairs with tweezers, or have an attendant or enslaved person do so in their home or the public baths. However, not everyone approved of Romans paying such close attention to their appearance.

The philosopher Seneca, who lived in Rome during the first century A.D., complained in a letter about how noisy it was to live in lodgings overlooking a bathhouse. “Besides those who just have loud voices,” he wrote, “imagine the skinny armpit-hair plucker whose cries are shrill so as to draw people’s attention and never stop except when he’s doing his job and making someone else shriek for him.” It’s hard for us to know how widespread armpit hair plucking actually was from Seneca’s letter, says Jerry Toner, director of studies in classics at Churchill College, since this grooming habit appears to be part of a larger issue the philosopher had with contemporary Romans. “He’s a big moralist, and he’s obviously condemning all this softness and luxury and leisure that’s going on in the bathhouse,” Toner says. “So he’s kind of hamming it up a bit, you know—all these people screaming at being plucked. But it definitely goes on reasonably commonly.”

Skin Scraping: The strigil was a cleaning tool (often made of bronze) that the Romans adopted from the Greeks. At public baths, Roman men and women cleaned themselves by covering their bodies with oil that they then scraped off with a strigil, along with any dirt and sweat on their skin. Romans might first exercise in the bath complexes’ open courtyards before cleaning with the strigil, in order to build up a sweat.

Archaeologists have discovered “toiletry sets” in which strigils are connected to oil containers, and they’ve even found strigils buried in graves in the city of Rome and in Bulgaria, where the Roman Empire’s eastern borders extended. The third-century A.D. Bulgarian grave contained a unique vessel shaped like a man’s head that the owner may have used to carry oil to scrape off with the strigil. It’s not clear why strigils turn up in graves, but scholars do know there was an association between strigils and athleticism, since athletes used them to scrape their bodies after exercising. Because of this, archaeologists nicknamed a fourth-century B.C. grave in Rome containing four bodies and two strigils the “Tomb of the Athlete.”

Ear Cleaning: Are you nervous about putting Q-tips in your ears? Well, Romans had it even worse. Archaeologists have discovered many tools known as “ear picks” or “ear scoops,” so-named because scholars theorize that Romans used them to clean wax out of their ears. These tools had a pick on one side and a tiny spoon or scoop on the other, and could be made of bronze, bone, or even glass. These picks and scoops could have been multiuse tools that Romans used for more than just cleaning their ears. For example, Moffett suggests Romans might have used them to scoop out oil and perfume from small bottles. Archaeologists often discover Roman tools like tweezers, nail cleaners, and ear picks or scoops connected together like a ring of keys, suggesting their shared status as toiletry and grooming items. The perfect accessory for the Roman guy or gal on the go.

Cleaning with Olive Oil and Fat in Ancient Rome

Olive oil and fat were commonly used in ancient Roman cosmetics and beauty aids. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The medic Hippocrates notes over sixty uses for olive oil in his writings, but by far the most common was the use of olive oil to moisturize and protect the skin. Both ancient Greek athletes and the patrons of the Roman baths used olive oil as a cleanser and moisturizer. They would begin by lathering themselves in oil and using a strigil (a curved blade almost always made of metal) to scrape off the dirt, sweat, and oil before bathing. [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

At the Roman baths, the dirt and skin-cell laden oil from men’s bodies would often be collected for use as a conditioner on women’s hair. The sweat-laden oil from gladiators was especially desirable in female beauty products. The routine was so important that some ancient tombs and burial sites include strigils and bottles of oil. Think of it as the first step in your double cleanse routine.

Olive oil was the most common cleanser-hydrator, but there were plenty of other fat-based options. The hydrating properties of beeswax continues to be used today, but animal fats were the go-to ingredients for ancient soap.Babylonians were making soap from animal fats around 2800 B.C., and similar techniques can be noted among ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians (the Phoenicians used goat’s tallow and wood ashes in theirs) before the turn of the millenium.

Urine — the Primary Cleaning Agent of Ancient Rome?

In Ancient Rome people washed their mouths out and brushed their teeth with urine. Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “In ancient Rome, pee was such big business that the government had special taxes in place just for urine sales. There were people who made their living just from collecting urine. Some would gather it at public urinals. Others went door-to-door with a big vat and asked people to fill it up. [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

The ways they used it are the last ones you’d expect. For example, they’d clean their clothes in pee. Workers would fill a tub full of clothing and pee, and then one poor soul would be sent in to stomp all over the clothing to wash it out. Which is nothing compared to how they cleaned their teeth. In some areas, people used urine as a mouthwash, which they claimed kept their teeth shining white. In fact, there’s a Roman poem that survives today in which a poet mocks his clean-toothed enemy by saying, “The fact that your teeth are so polished just shows you’re the more full of piss.”“

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Ancient Roman soap (and face masks) used urine as its principle active “lightening” ingredient. The urine was collected from public latrines and pots that functioned as urinals. Urine was so important in Roman cleansing technologies — including the tanning industry and laundering clothes — that the Roman emperor Vespasian imposed a tax on it. Arguably the most disgusting use of urine was as a teeth whitener. The Romans believed that it would halt the aging process by preventing tooth decay. As a result, they used it as a mouthwash and mixed it with pumice to make toothpaste. It was so effective that it continued to be used in toothpaste into the eighteenth century. The best (and most effective) urine, should you care, was believed to be from Portugal. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 23, 2017]

For the especially devoted ancient Greek or Roman looking for a little more heat in their mudbath, alligator and crocodile excrement was a vital ingredient. Before you get judgmental about this, bear in mind that snail slime is all the rage these days and there is a New York spa that specializes in a “bird poop facial.” All I can say is that Romans found it very effective.

Farting in Antiqity

Farting has been the source of embarrassment since the dawn of history. The Sumerians of Mesopotamia described it as did the Greek playwright Aristophanes. Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast: In his biography of the emperor Claudius, the Roman writer Suetonius records that Claudius “intended to publish an edict ‘allowing to all people the liberty of giving vent at table to any distension occasioned by flatulence,’ upon hearing of a person whose modesty, when under restraint, had nearly cost him his life.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 4, 2016]

But it’s not all downside, Dr Jessica Baron, a historian of science at the University of Notre Dame, told me that some doctors connected farting to sex, “In fact [the second-century physician] Galen sometimes refers to flatulent, or ‘windy’ foods as aphrodisiacs, as do much later Galenists.

"The ancient fear of farting is justified when we consider the surprising number of the stories — that is, more than none — about wars provoked by farts. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, a fart set off a chain of events that led to a revolt against King Apries of Egypt. The repercussions were even worse in first-century Jerusalem: The historian Josephus tells us that an irreverent Roman soldier lowered his pants, bent over, and “spoke such words as you might expect upon such a posture.” The incident took place shortly before the Passover and caused a riot that led to the deaths of 10,000 people."

Strangely though, as Elizabeth Lopatto traced in her brief medical history of farting, the causes of “excessive flatulence” evaded medical science for millennia. As late as 1975, MD Levitt could remark, “there are no data available that prove excessive flatulence is actually caused by the presence of excessive intestinal gas.” It was only when Levitt conducted an experiment pumping the gas argon into patients via their rectum that he noted that people farted at the same rate that they were filled with gas. Astonishing. Curiously, it was not until 1998 that Levitt proposed a methodology for distinguishing between excess gas caused by swallowing too much air, and flatulence that resulted from processes that took place in the gut.

Roman-Era Fart That Killed 10,000 People

In “The Jewish War”, an A.D. 75 historical text, Josephus (A.D. 37-100) describes a Roman soldier whose taunting public flatulence triggered a riot that to 10,000 deaths. Josephus wrote in that the soldier was in front of a group of Jewish people celebrating Passover when he “pulled back his garment, and cowering down after an indecent manner, turned his breech to the Jews, and spake such words as you might expect upon such a posture.” In response, some of the Jewish people began throwing stones at the soldier and his companions. When more soldiers arrived on the scene at the Temple, a riot ensued, and many of the people who died were Jews who were trampled to death as they tried to flee the Roman Army. [Source: Ancient Origin, August 20, 2022]

Josephus wrote in “Jewish Wars”, Book II Chapter XI: ...when the multitude were come together to Jerusalem, to the feast of unleavened bread, and a Roman cohort stood over the cloisters of the temple, (for they always were armed and kept guard at the festivals, to prevent any innovation which the multitude thus gathered together might make,) one of the soldiers pulled back his garment, and cowering down after an indecent manner, turned his breech to the Jews, and spake such words as you might expect upon such a posture. At this the whole multitude had indignation, and made a clamour to Cumanus, that he could punish the soldier... They riot, throwing stones at soldiers etc. Reinforcements show up, the crowd becomes a crush. ...the violence with which they crowded to get out was so great, that they trod upon each other, and squeezed one another, till ten thousand of them were killed....”

Cumanus was the name of the Roman soldier. The only sources for him are Tacitus and Josephus, with only Josephus mentioning the incident.

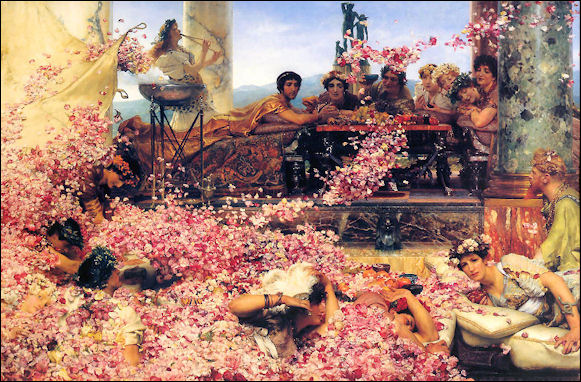

Roses of Heliogabalus

Ancient Roman Perfumes and Fondness for Roses

Perfume shops were a common sight in ancient Rome. Entire streets in Rome were lined with them. Perfumes were sold as powders made from crushed flower petals and spices, liquids made from oils squeezed from flowers, resins and spices, and extracts from a single source such almond, rose or quince.

Like the Greeks, Romans applied different scents to different parts of their bodies. Roman soldiers perfumed themselves with cedar, pine ginger, mimosa, tangerine, orange and lemon. Aristocratic women were massaged after a bath by salves with a different fragrance for each part of their body. People even perfumed the soles of their feet.

Greeks and Romans not only put perfume on themselves they also dowsed their furniture, hair and clothes with it. Romans even scented their household pets, horses and donkeys with perfume and fragrance. The practice of wearing perfumes ended with the coming of the Christian era. Christians regarded wearing perfume as self-indulgent.

The Romans were obsessed with roses. Rose water bathes were available in public baths and roses were tossed in the air during ceremonies and funerals. Theater-goers sat under awning scented with rose perfume; people ate rose pudding, concocted love potions with rose oil, and stuffed their pillows with rose petals. Rose petals were a common feature of orgies and a holiday, Rosalia, was name in honor of the flower.

Nero bathed in rose oil wine. He once spent 4 million sesterces (the equivalent of $200,000 in today's money) on rose oils, rose water, and rose petals for himself and his guests for a single evening. At parties he installed silver pipes under each plate to release the scent of roses in the direction of guests and installed a ceiling that opened up and showered guests with flower petals and perfume. According to some sources, more perfumes was splashed around than were produced in Arabia in a year at his funeral in A.D. 65. Even the processionary mules were scented.

Roman Cup Found with Ambergis

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: When archaeologists excavating a large third- to fifth-century A.D. cemetery in the ancient Roman city of Augustodunum (modern Autun, France) they found an extremely rare and incalculably valuable Roman glass vessel in the stone sarcophagus of one of the city’s wealthiest citizens, they were stunned by its remarkable state of preservation. Though the cup was discovered in many pieces, its fragments were well enough preserved to easily make out its decorative patterns and to read its inscription, “VIVAS FELICITER,” or “Live happily.” Only 10 examples of this type of vessel, known as a cage cup, have survived from antiquity. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022

Roman cage cup described above

After they were unearthed, the cup’s fragments were sent to Germany for restoration, a multiyear process that has revealed new details about this extraordinary artifact. It is clear that while the artist who carved the cup from a block of glass was extremely skilled, they nevertheless made a mistake that required them to add the letter “C” in the inscription later using a remelted piece of glass.

Conservators also sampled the interior of the cup and found that it had once contained oils, plants, flowers, and ambergris, a rare waxy substance from the stomach contents of sperm whales. Ambergris, also called “sea truffle” or “whale vomit,” served in antiquity as a base for perfume, food, and medicine. The Augustodunum cage cup provides the earliest archaeological evidence for use of this highly prized material.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024