Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

ANCIENT ROMAN FABRICS AND MATERIALS

Roman bikini

Most cloth was made from wool and linen. Cotton and silk were also used but to a much lesser degree. The Romans used bare-breasted virgins to beat away moths and beetles that ate their wool garments. Other cultures tried cow manure and garlic. Now we use moth balls and thorough washing. By the 1st century B.C., Roman aristocrats wore silk garments. At the beginning of the Christian era, Rome was importing so much silk that the Roman Emperor Tiberius prohibited Romans from wearing it. In one year, Rome reportedly paid 22,000 pounds of gold for silk shipments.

Some conservative families in Rome prided themselves upon wearing garments made at home; the Emperor Augustus is said to have worn, except on special occasions, the handiwork of the ladies of his family as an example of simplicity in a period of general extravagance.

The Greeks and Romans used leather and developed fairly sophisticated methods of tanning. Leather was used as money and shoes were a sign of status. Pliny the Elder wrote in the A.D. 1st century, "Hides were tanned with bark, and gallnuts...were used." Gallnuts are caused by insects laying eggs in the buds of oaks trees and sometimes are still used today in the tanning process.

For clothes woolen goods were the first to be used, and naturally so, since the early inhabitants of Latium were shepherds, and woolen garments best suited the climate. Under the Republic, wool was almost exclusively used for the garments of both men and women, as we have seen, though the subligaculum was frequently, and the woman’s tunic sometimes, made of linen. The best native wools came from Calabria and Apulia; wool from the neighborhood of Tarentum was the finest. Native wools did not suffice, however, to meet the great demand, and large quantities were imported. Linen goods were early manufactured in Italy, but were used chiefly for other purposes than clothing until the days of the Empire; only in the third century of our era did men begin to make general use of them.

The finest linen came from Egypt, and was as soft and transparent as silk. Little is positively known about the use of cotton, because the word carbasus, the genuine Indian name for it, was used by the Romans for linen goods also; hence when we meet the word we cannot always be sure of the material meant. Silk, imported from China directly or indirectly, was first used for garments under Tiberius, and then only in a mixture of linen and silk (vestes sericae). These were forbidden for the use of men in his reign, but the law was powerless against the love of luxury. Garments of pure silk were first used in the third century. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN CLOTHES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN FOOTWEAR AND HATS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JEWELRY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BEAUTY AND COSMETICS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HAIR IN ANCIENT ROME: STYLES, BEARDS, SHAVING, BARBERS, SLAVE STYLISTS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Roman Textile Industry and Its Influence” by Penelope Walton Rogers, Lise Bender Jorgensen, et al. (2010) Amazon.com;

“Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture” by Jonathan Edmondson and Alison Keith (2009) Amazon.com;

“How the Greeks and Romans Made Cloth” (Cambridge School Classics Project)

Amazon.com;

“Ancient And Medieval Dyes” by William Ferguson (2012) Amazon.com;

“Spinning Fates and the Song of the Loom: The Use of Textiles, Clothing and Cloth Production as Metaphor, Symbol and Narrative Device in Greek and Latin Literature” by Giovanni Fanfani, Mary Harlow, et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean” by E.J.W. Barber (1992) Amazon.com;

“Fabric of Civilization” by Virginia Postrel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History” by Kassia St. Clair (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Tools, Textiles and Contexts: Investigating Textile Production in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age” by Eva Andersson Strand and Marie-Louise Nosch (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Textiles: Production, Crafts and Society” by Marie-Louise Nosch, C. Gillis (2007) Amazon.com;

“First Textiles: The Beginnings of Textile Production in Europe and the Mediterranean” by Małgorzata Siennicka, Lorenz Rahmstorf, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Competition of Fibres: Early Textile Production in Western Asia, Southeast and Central Europe (10,000–500 BC)” by Dr. Wolfram Schier and Prof. Dr Susan Pollock (2020) Amazon.com;

“Roman Clothing and Fashion” by Alexandra Croom (2012) Amazon.com;

“The World of Roman Costume” by Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante (2001) Amazon.com;

“Roman Women’s Dress: Literary Sources, Terminology, and Historical Development”

by Jan Radicke, Joachim Raeder (2022) Amazon.com;

“Masculinity and Dress in Roman Antiquity” (Routledge) by Kelly Olson (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Clothes Production in Ancient Rome

Romans improved on Greek cloth making methods by replacing the warp-weighted loom with the more efficient two-armed loom. The Romans built textile factories and improved trade of cloth by building good roads. Wool garments required special attention to keep from shrinking or losing their shape. Public laundries were set up. They employed “fullers” who washed, whitened, redyed and pressed the garments. The fullers press consisted of two upright planks and a large screw top. Turned by a crank it flattened clothes between the planks. Urine was used as bleach.

Roman bikini

In the old days the wool was spun at home by the women slaves, working under the eye of the mistress, and woven into cloth on the family loom. This custom was kept up throughout the Republic by some of the proudest families. Augustus wore such homemade garments. By the end of the Republic, however, this was no longer general, and, though much of the native wool was worked up on the farms by the slaves, directed by the vilica, cloth of any desired quality could be bought in the open market. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“It was formerly supposed that the garments came from the loom ready to wear, but this view is now known to be incorrect. We have seen that the tunic was made of two separate pieces sewed together, and that the toga had to be measured, cut, and sewed to fit the wearer, and that even the coarse paenula could not have been woven in one piece. But ready-made garments, though perhaps of the cheaper qualities only, were on sale in the towns as early as the time of Cato; under the Empire the trade reached large proportions. It is remarkable that, though there were many slaves in the familia urbana, it never became usual to have soiled garments cleansed at home. All garments showing traces of use were sent by the well-to-do to the fullers (fullones) to be washed, whitened (or redyed), and pressed. The fact that almost all were of woolen materials made skill and care the more necessary. |+|

“The Roman armies sometimes adopted the bracae when they were campaigning in the northern provinces. Tacitus tells a story of the offense given by Caecina on his return from his campaign in Gaul because he continued to wear the bracae while be was addressing the toga-clad citizens of the Italian towns through which he passed. (Hist. 2.20).” |+|

Ancient Roman Colors

“White was the prevailing color of all articles of dress throughout the Republic, in most cases the natural color of the wool, as we have seen. The lower classes, however, selected for their garments shades that required cleansing less frequently, and found them, too, in the undyed wool. From Canusium came a brown wool with a tinge of red, from Baetica in Spain a light yellow, from Mutina a gray or a gray mixed with white, from Pollentia in Liguria the dark gray (pulla), used, as has been said, in public mourning. Other shades from red to deep black were furnished by foreign wools. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Almost the only artificial color used for garments under the Republic was purpura, which seems to have varied from what we call garnet, made from the native trumpet shell (bucinum or murex), to the true Tyrian purple. The former was brilliant and cheap, but likely to fade. Mixed with the dark purpura in different proportions, it furnished a variety of permanent tints. One of the most popular of these tints, violet, made the wool cost twenty dollars a pound, while the genuine Tyrian cost at least ten times as much. |+|

Probably the stripes worn by the knights and senators on the tunics and togas were much nearer our crimson than purple. Under the Empire the garments worn by women were dyed in various colors, and so, too, perhaps, the fancier articles worn by men, such as the lacerna and the synthesis. The trabea of the augur seems to have been striped with scarlet and “purple,” the paludamentum of the general to have been at different times white, scarlet, and “purple,” and the robe of the triumphator “purple.

Phoenician Purple Dye

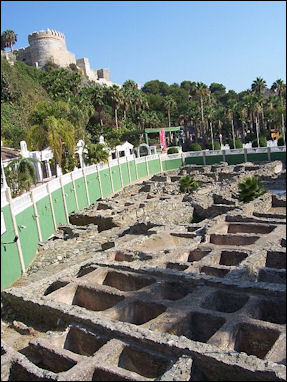

Vestiges of purple dye

industry in Lebanon Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Romans were obsessed with purple textiles.Tyrian or imperial purple dye was made from the desiccated glands of the predatory sea snails found in the Eastern Mediterranean and off the coast of Morocco. The dark purple-red dye was used on ceremonial clothing for high-status individuals; it was particularly valued because it didn’t fade but it was expensive (not to mention smelly) to manufacture. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 27, 2022]

Purple was greatly prized among the Greeks and in the ancient Mediterranean world and Europe. The Phoenician City of Tyre grew rich from the sale of a purple-dyed textiles that were used to denote royalty. The dye was produced from murex, a trumpet-shaped marine snail still found among rocks in the eastern Mediterranean today. Piles of the shells and large vats indicated that dye production was carried out on an industrial scale. In Sidon, archeologist found a 300-foot-long mound of murex shells.

According to legend purple was discovered by the Phoenician god Melkarth, whose dog bit into a seashell, resulting in his mouth becoming a rich shade of purple. Other have said the dye was discovered by noting that people who ate the snail had purple lips. Royal purple was produced as early as 1200 B.C. The dye was made of urine, sea water and ink from the bladders of the murex snails. To extract the snails, the shells were put in a vat where their putrifying bodies excreted a yellowish liquid. Depending on how much water was added the liquid produced hues ranging from rose to dark purple.

"Born to the purple" became a common expression to describe royalty. Purple cloth was treasured by the Greeks and Romans and remained extremely valuable through Byzantine times. One gram of pure purple die was worth 10 to 20 times its weight in gold. Some of the richest people in ancient Phoenician were purple dye merchants. Purple is no longer made from sea shells in the eastern Mediterranean but it is still done in Oaxaca, Mexico. In the winter “ Purpura” mollusks are collected from rocks and opened and the purple dye is applied to yarn right there in the spot.

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN TRADE: COLONIES, PURPLE DYE, AND MINES factsanddetails.com

Fabrics and Colors of Women’s Clothes in Ancient Rome

Woman's dress in Rome was not distinguished from man's by the cut, but rather by the richness of the material and the brilliance of the color. To linen and wool she preferred the cotton stuffs that came from India after the Parthian peace, assured by Augustus and confirmed by the victories of Trajan, had guaranteed the security of imports; above all she loved the silks which the mysterious Seres exported annually to the empire from the country which we nowadays call China. Since the reign of Nero silk caravans had come by the land routes across Asia, then from Issidon Scythica (Kashgar) to the Black Sea, or else through Persia and down the Tigris and Euphrates to the Persian Gulf, or by boat down the Indus and then by ship to the Egyptian ports of the Red Sea. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Silk materials were not only more supple, lighter, and iridescent, they also lent themselves better than all others to skilful manipulation. The affectores with their ingredients reinforced the original colors; the injector es denaturalised them; and the various dyers, the purpurarii, flammarii, crocotarii, violarii, knew cunning dyes equalling in number the vegetable, animal, and mineral resources at their disposal; chalk and soapwort and salt of tartar for white; saffron and reseda for yellow; for black, nut-gall; woad for blue; madder, archil, and purple for dark and lighter shades of red. Mindful of Ovid's counsels the matrons adapted their complexions to the colors of their dresses and harmonised them so skilfully that when they went into the city they lit the streets with the bravery of their multicolored robes and shawls and mantles, whose brilliance was often further enhanced by dazzling embroideries like those which adorned the splendid palla of black in which Isis appeared to Apuleius!

It was the matron's business to complete her costume with various accessories foreign in their nature to man's dress, which further accentuated the picturesqueness of her appearance. While a man normally wore nothing on his head, or at most, if the rays of the sun were too severe or the rain beat too fiercely down, threw a corner of his toga or pallium over his head or drew down the hood (cucullus) of his cloak (paenida), the Roman woman, if not wearing a diadem or mitra, passed a simple bandeau (vitta) of crimson through her hair, no longer imprisoned in its net, or else a tutulus similrr to the bandeau of the fiaminicae, which broadened in the center to rise above the forehead in the shape of a cone. She often wore a scarf (jocale) knotted at the neck. The mappa dangling from her arm served to wipe dust or perspiration from her face (orarium, sudarium). We must, however, beware of assuming that the practice of blowing the nose came in early, for the only Latin word which can fairly be translated as handkerchief (muccinium) is not attested before the end of the third century. In one hand she often flourished a fan of peacocks' feathers (flabellum), with which she also brushed away the flies (muscarium). In fine weather she carried in her other hand, unless she entrusted it to a serving woman by her side (pedisequa) or to her escort, a sunshade (umbella, umbraculum), usually covered in bright green. She had no means of closing it at will, as we can ours, so she left it at home when there was a wind.

Thus equipped, "the fair" could face the critical eye of their fellow women and challenge the admiration of the passers-by. But it is certain that the complexity of their array, combined with a coquetry not peculiar to their day, must have drawn out the time demanded by their morning toilet far beyond that needed by their husbands. This was, hqwever, a matter of no account, for the women of Rome were not busy people like their men, and to confess the truth they took no part in the public life of Rome except in its hours of leisure.

Roman-Era ‘Dry Cleaners’

In 2023, archaeologists announced the discovery of a a fullonica — an ancient equivalent of a dry cleaner — in the Insula 10 of Regio IX along the Via di Nola in Pompeii. In ancient Rome, a fullonica, sometimes referred to as a fullery, was a shop where launderers were paid to do people’s washing.[Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, March 1, 2023]

Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald: Because soap was not yet invented, ancient Romans used urine — both animal and human — as laundry detergent, according to Pompeii Archaeological Park. The urine was collected in pots found along the city streets.Urine contains ammonia, a base substance, which cleans dirt and grease stains by counteracting their slightly acidic nature, the Smithsonian Magazine reported.

Ancient Romans would bring their clothes to the fullonica and pay for laundry services, according to the World Encyclopedia. Laundry workers would first wash the clothes in vats filled with water and urine then walk barefoot on the clothes for a period of time. Next, the workers would rinse the clothes by hand and beat them with a stick to remove any lingering dirt. Once dirt and stains were gone, the clothes were dried on racks and either delivered to or picked up by their owners.

Ten other fullonica shops have been found in Pompeii so far, according to the World History Encyclopedia. In addition to the laundry shop, excavations in Insula 10 of Regio IX also unearthed a house with an oven and upper cell as well as a series of holes likely dug for volcanic rocky quarrying, the release said. Archaeological excavations are ongoing and hope to reveal more about life in the ancient city.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024