Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

ANCIENT ROMAN STYLE

Roman toga Upper class Romans cared a great deal about the way they looked and could be quite fashion conscious. Upper class women appear to have taken great pains in arranging the hair, and possessed a fondness for ornaments—necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and costly jewels. A 1,600-year-old fresco found at a villa in Sicily showed a pair of bikini-clad women tossing a ball. Brassieres were called maxmillarre. Romans invented the earliest known button. The earliest ones were inserted into a loop of thread or fabric. The buttonhole was not widely used until the 13th century.

Mary Beard told Smithsonian magazine: “Despite the popular image, they didn’t usually wear togas (those were more the ancient equivalent of a tux). In any Roman town you'd find people in tunics, even trousers, and brightly colored ones at that. Juvenal said: “There are many parts of Italy, to tell the truth, in which no man puts on a toga until he is dead”. A typical Roman wore a tunic.

From the earliest to the latest times the clothing of the Romans was very simple, consisting ordinarily of two or three articles only, besides the covering of the feet. These articles varied in material, style, and name from age to age, it is true, but their forms were practically unchanged during the Republic and the early Empire. The mild climate of Italy and the hardening effect of physical exercise on the young made unnecessary the closely fitting garments to which we are accustomed. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Contact with the Greeks on the south and perhaps the Etruscans on the north gave the Romans a taste for the beautiful that found expression in the graceful arrangement of their loosely flowing robes. The clothing of men and women differed much less than in modern times, but it will be convenient to describe their garments separately. Each article was assigned by Latin writers to one of two classes and called, from the way it was worn, indutus (“put on”) or amictus (“wrapped around”). To the first class we may give the name of undergarments, to the second outer garments, though these terms very inadequately represent the Latin words. |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

CLOTHES-MAKING IN ANCIENT ROMAN: FABRICS, WEAVING, COLORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN FOOTWEAR AND HATS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JEWELRY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BEAUTY AND COSMETICS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HAIR IN ANCIENT ROME: STYLES, BEARDS, SHAVING, BARBERS, SLAVE STYLISTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Clothing and Fashion” by Alexandra Croom (2012) Amazon.com;

“The World of Roman Costume” by Judith Lynn Sebesta and Larissa Bonfante (2001) Amazon.com;

“Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture” by Jonathan Edmondson and Alison Keith (2009) Amazon.com;

“Roman Women’s Dress: Literary Sources, Terminology, and Historical Development”

by Jan Radicke, Joachim Raeder (2022) Amazon.com;

“Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography” by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns, Marta Zuchowska Amazon.com;

“Masculinity and Dress in Roman Antiquity” (Routledge) by Kelly Olson (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Military Clothing (1): 100 BC–AD 200 (Men-at-Arms)

by Graham Sumner (2002) Amazon.com;

“Roman Military Clothing (2): AD 200–400" by Graham Sumner (2003) Amazon.com;

“Roman Military Clothing (3): AD 400–640" by Raffaele D’Amato and Graham Sumner (2005) Amazon.com;

“Costumes of the Greeks and Romans” by Thomas Hope (1962) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z” by Liza Cleland, Glenys Davies, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

“Dress in Mediterranean Antiquity: Greeks, Romans, Jews, Christians” by Alicia J. Batten, Kelly Olson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine Costume” by Mary G. Houston (2011)

Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Ancient Roman Clothes

2 3.jpg) The characteristic dress of the men was the toga, a loose garment thrown about the person in ample folds, and covering a closer garment called the tunic (tunica). The Romans wore sandals on the feet, but generally no covering for the head. The dress of a Roman woman consisted of three parts: the close-fitting tunica; the stola, a gown reaching to the feet; and the palla, a shawl large enough to cover the whole figure. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The characteristic dress of the men was the toga, a loose garment thrown about the person in ample folds, and covering a closer garment called the tunic (tunica). The Romans wore sandals on the feet, but generally no covering for the head. The dress of a Roman woman consisted of three parts: the close-fitting tunica; the stola, a gown reaching to the feet; and the palla, a shawl large enough to cover the whole figure. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

“The Greeks and Romans didn’t wear trousers. . Bracae “trousers,” were a Gallic article that was not used at Rome until the time of the latest emperors. Nationes bracatae in classical times was a contemptuous expression for Gauls in particular and for barbarians in general. The habit of wearing them appears to have been introduced by nomadic Asian horsemen tribes. Tunics were not suitable for riding and consequently a short leather trouser was developed that provided freedom both in the saddle and on foot. The Romans associated these garments with barbarian tribes on the borders of the empire. After the fall of the Roman Empire, trousers made of wool, linen, leather, silk and cotton were worn.

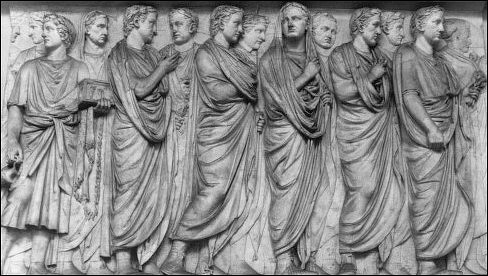

A dinner dress worn at table over the tunic by the ultrafashionable, and sometimes dignified by the special name of vestis cenatoria, or cenatorium alone. These Romans are dressed in tunics and cloaks. A relief from the Arch of Constantine, Rome.It was not worn out of the house except during the Saturnalia, and was usually of some bright color. Its shape is unknown. The laena and abolla were very heavy woolen cloaks; the latter was a favorite with poor people who had to make one garment do duty for two or three. It was used especially by professional philosophers, who were proverbially careless about their dress. Cloaks of several shapes were worn.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Boys wore the subligaculum, and, the tunica; it is very probable that no other articles of clothing were worn by either boys or girls of the poorer classes. Besides these garments, children of well-to-do parents wore the toga praetexta, which the girl laid aside on the eve of her marriage and the boy when he reached the age of manhood. Slaves were supplied with a tunic, wooden shoes, and in stormy weather a cloak, probably the paenula. This must have been the ordinary garb of the poorer citizens of the working classes, for they would have had little use for the toga, at least in later times, and could hardly have afforded so expensive a garment.” |+|

What Roman Clothing Says About Roman Society

According to Encyclopedia.com: Romans were also a sharply divided society, with a small number of very wealthy people and masses of poor people. Wealthy Roman men simply did not go outside without a toga draped over a tunica. Respectable women also had an official outfit, consisting of a long dress called a stola, often worn beneath a cloak called a palla. From the lowest classes of society up through royalty, men wore the toga to public ceremonies. It was difficult for the poor people to afford a toga or a stola, yet they had to wear one on certain occasions. Even the poorest Roman citizen, however, was distinguished from slaves or barbarians (the name Romans gave to people from other countries), who were banned from wearing Roman clothes like the toga. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Romans were very careful about the way they dressed. So careful, in fact, that they had a number of rules about who could wear certain items and how certain items should be worn. Romans created some of the first sumptuary laws, which regulated the color and type of clothing that could be worn by members of different social classes. (Sumptuary relates to personal expenditures especially on luxury items.) They also had unwritten rules about such things as the length of a toga or stola and demands for different togas for different social occasions. Wealthy Romans had slaves who helped their masters choose and adjust their clothing to just the right style. Observers have written about how intense the pressure was to wear clothing correctly in ancient Rome.

Because their empire grew so great and took Romans into very different climates, the Romans became the first major society to wear seasonal clothing — that is, clothes for both warm and cold climates. They made warm winter boots and the first known raincoat. The spread of their empire also meant that Roman traditions spread into other countries, particularly throughout Europe and into the British Isles. Variations on ancient Roman costume can still be seen in the vestments, or priestly clothing, worn by members of the Roman Catholic Church.

Most of what we know about Roman clothing comes from evidence left by the wealthiest Romans. The many statues and paintings that have survived, and the various writings from the time, all discuss the clothing styles of those Romans who were very well off. It is likely that poorer Romans wore similar garments, though of much lower quality, but it may be that there were other clothing items that have simply been lost to history.

Undergarments in Ancient Rome

mamillare

The closest thing Romans had to underwear was a subligaculum — a pair of shorts or loincloth wrapped around the lower body — worn both by men and women. You can see it some images of gladiators, athletes and actors on stage. The subligaculum was sometimes worn under a tunic but men some men wore the subligaculum and nothing else, even they were running for public office. Women also sometimes wore a band of cloth or leather around their upper body (strophium or mamillare) that served as bra. [Source: Listverse, October 16, 2009 ]

We are told that in the earliest times the subligaculum was the only undergarment worn by the Romans, and that the family of the Cethegi adhered to this ancient practice throughout the Republic, wearing the toga immediately over it. This was done, too, by individuals who wished to pose as the champions of old-fashioned simplicity, as, for example, the Younger Cato, and by candidates for public office. In the best times, however, the subligaculum was worn under the tunic or was replaced by it. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Besides the subligaculum and the tunica the Romans had no regular underwear. Those who were feeble through age or ill health sometimes wound strips of woolen cloth (fasciae), like the modern spiral puttees, around the legs for the sake of additional warmth. These were called feminalia or tibialia according as they covered the upper or lower part of the leg. Feeble persons might also use similar wrappings for the body (ventralia) and even for the throat (focalia), but all these were looked upon as badges of senility or decrepitude and formed no part of the regular costume of sound men.

One Roman stationed near Scotland wrote to his mother's requesting long underwear. Soldiers there wore hooded cloaks during the cold Scottish winters. . The endromis was something like the modern bath robe, used by the men after vigorous gymnastic exercise to keep from catching a cold. Slaves and laborers found togas restricting, and they preferred wearing just a tunic when they worked. Workers were often called tunicati after the simple knee-length tunic they wore. Slaves often wore only a loincloth.

Bras in Ancient Rome

Erin Blakemore wrote in National Geographic History: Though it’s unclear when the first of the bra’s many precursors was invented, historians have found references to bra-like garments in ancient Greek works like Homer’s Iliad, which depicts the goddess Aphrodite removing a “curiously embroidered girdle” from her bosom, and Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, in which a woman withholding sex from her husband teases him by saying she’s taking off her strophion, clumsily translated as “breast-band.” [Source Erin Blakemore, National Geographic History, October 4, 2023]

Scholars are divided on whether Greek and Roman women wore bra-like garments for support, style, or both. Historian Mireille Lee writes that though the strophion had sexual and gendered connotations, it’s difficult to determine exactly what, if anything, ancients wore beneath their clothes — there’s only a single artistic depiction from the time that shows a woman wearing a strophion beneath clothing.

In another example, archaeologists excavating Sicily’s Villa del Casale discovered a mosaic from the 4th-century A.D. featuring athletic Roman women with breasts were bound by a garment scholars think may have been an amictorium, a linen garment whose bikini-like appearance earned the mural’s subjects the nickname “Bikini Women.” Another Roman breast covering, the mamillare, was made of sturdier leather. But as classicist Jan Radicke writes, though Roman women seem to have “had several options for covering and shaping their breasts…We have too little evidence to make a determination” as to what the garments actually looked like or whether their uses were decorative, sexual, or simply supportive.

Roman Tunics

4.jpg) The tunic was also adopted in very early times and came to be the chief article of the kind covered by the word indutus. It was a plain woolen shirt, made of two pieces, back and front, which were sewed together at the sides. It usually had very short sleeves, covering hardly half of the upper arm.. It was long enough to reach from the neck to the calf, but if the wearer desired greater freedom for his limbs he could shorten it by merely pulling it through a girdle or belt worn around the waist. Tunics with sleeves reaching to the wrists (tunicae manicatae), and tunics falling to the ankles (tunicae talares) were not unknown in the late Republic, but were considered unmanly and effeminate. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The tunic was also adopted in very early times and came to be the chief article of the kind covered by the word indutus. It was a plain woolen shirt, made of two pieces, back and front, which were sewed together at the sides. It usually had very short sleeves, covering hardly half of the upper arm.. It was long enough to reach from the neck to the calf, but if the wearer desired greater freedom for his limbs he could shorten it by merely pulling it through a girdle or belt worn around the waist. Tunics with sleeves reaching to the wrists (tunicae manicatae), and tunics falling to the ankles (tunicae talares) were not unknown in the late Republic, but were considered unmanly and effeminate. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The tunic was worn in the house without any outer garment and probably without a girdle; in fact it came to be the distinctive house-dress as opposed to the toga, the dress for formal occasions only. The tunic was also worn with nothing over it by the citizen while at work, but no citizen of any pretension to social or political importance ever appeared at social functions or in public places at Rome without the toga over it; and even then, though it was hidden by the toga, good form required the wearing of the girdle with it. Two tunics were often worn (tunica interior, or subucula, and tunica exterior), and persons who suffered from the cold, as did Augustus for example, might wear an even larger number when the cold was very severe. The tunics intended for use in the winter were probably thicker and warmer than those worn in the summer, though both kinds were of wool. |+|

“The tunic of the ordinary citizen was the natural color of the white wool of which it was made, without trimmings or ornaments of any kind. Knights and senators, on the other hand, had stripes of crimson, narrow and wide, respectively, running from the shoulders to the bottom of the tunic both behind and in front. These stripes were either woven in the garment or sewed upon it. From them the tunic of the knight was called tunica angusti clavi (or angusticlavia) , and that of the senator lati clavi (or laticlavia). Some authorities think that the badge of the senatorial tunic was a single broad stripe running down the middle of the garment in front and behind, but unfortunately no picture has come down to us that absolutely decides the question. It seems probable that the knight’s tunic had two stripes, one running from each shoulder. Under this official tunic the knight or senator wore usually a plain tunica interior. When in the house he left the outer tunic unbelted in order to display the stripes as conspicuously as possible. “|+|

The tunic was formed by two widths sewed together. It was slipped over the head and fastened round the body by a belt. It was draped to fall unequally, reaching only to the knees in front but somewhat below them behind. The woman's tunic tended to be longer than the man's and might even reach to the heel (tunica talaris). The military tunic was shorter than the civilian's, the ordinary citizen's than that of the senator which was striped by a broad, vertical band of purple (tunica laticlavia). People sensitive to cold might wear two subuculae instead of one, or even go the length of wearing In winter as in summer the tunic had short sleeves, just covering the top of the arm, and it was not until the empire that this length could be exceeded with propriety. This explains why even the slaves were allowed to wear warm gloves during the great cold, and why it was necessary to have an amictus above the indumenta. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Toga

The toga worn by Romans was essentially a cloak worn over a sleeveless tunic. The toga was worn mainly by the upper classes. When a 16-year old was presented with his first toga virilism , it was important rite of passage. Romans carefully draped they folds of their toga over their shoulders and gave them a lot of attention sort of like Indian women in saris. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum

Of the outer garments or wraps the most ancient and the most important was the toga (cf. tegere). It goes back to the very earliest time of which tradition tells, and was the characteristic garment of the Romans for more than a thousand years. It was a heavy, white, woolen robe, enveloping the whole figure, falling to the feet, cumbrous but graceful and dignified in appearance. All its associations suggested formality. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

relief with three styles of toga

“When the Roman of old tilled his fields, he was clad only in the subligaculum; in the privacy of his home or at his work the Roman of every age wore the comfortable, blouse-like tunica; but in the Forum, in the comitia, in the courts, at the public games, and wherever social forms were observed, he appeared and had to appear in the toga. In the toga he assumed the responsibilities of citizenship; in the toga he took his wife from her father’s house to his own; in the toga he received his clients, also toga-clad; in the toga he discharged his duties as a magistrate, governed his province, celebrated his triumph; and in the toga he was wrapped when he lay for the last time in his atrium. No foreign nation had a robe of the same material, color, and arrangement; no foreigner was allowed to wear it, though he lived in Italy or even in Rome itself; even the banished citizen left the toga, with his civil rights behind him. Vergil merely gave expression to the national feeling when he wrote the proud verse (Aeneid I, 282): Romanos, rerum dominos, gentemque togatam.

“The general appearance of the toga is well known; of few ancient garments are pictures so common and in general so good. They are derived from numerous statues of men clad in it, which have come down to us from ancient times, and we have, besides, full and careful descriptions of its shape and of the manner of wearing it, left to us by writers who had worn it themselves. The cut and draping of the toga varied from generation to generation. In its earlier form it was simpler, less cumbrous, and more closely fitted to the figure than in later times. Even as early as the classical period its arrangement was so complicated that the man of fashion could not array himself in it without assistance. A few forms of the toga will be discussed here, but it is best studied in Miss Wilson’s treatise. |+|

“In its original form the toga was probably a rectangular blanket much like the plaid of the Highlanders, except for the lack of color, as that of the private citizen seems to have been always of undyed wool. Its development into its characteristically Roman form began when one edge of the garment came to be curved instead of straight. The statue in Florence known as the “Arringatore”, supposed to date from the third century B.C., shows a toga of this sort, so cut or woven that the two lower corners are rounded off. Such a toga for a man who was five feet six inches in height would be about four yards long, and one yard and three-quarters in width. The toga was thrown over the left shoulder from the front, so that the curved edge fell over the left arm, and the end hung in front so as to fall about halfway between the knee and the ankle. On the left shoulder a few inches of the straight or upper edge were gathered into folds. The long portion remaining was now drawn across the back, the folds were passed under the right arm, and again thrown over the left shoulder, the end falling down the back to a point a trifle higher than the corresponding end in front. The right shoulder and arm were free, the left covered by the folds.” |+|

How to Wear a Toga

Statues of the third and second centuries B.C. show a larger and longer toga, more loosely draped, drawn around over the right arm and shoulder instead of under the arm as before. By the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Empire the toga was of the same size as that just described, but with some difference in shape and draping. For a man who was five feet six inches in height it would have been about four yards and a half in length and two and two-thirds yards across at the widest part. The lower corners were rounded much as before. From each of the upper corners a triangular section was cut. This toga was then folded lengthwise so that the lower section was deeper than the other. The end A hung in front, between the feet, not quite to the ground. The section AFEB was folded over. The folded edge lay on the left shoulder against the neck. The rest of the folded length was then brought around under the right arm and over the left shoulder again, as in the case of the earlier toga. The upper section fell in a curve over the right hip, and then crossed the breast diagonally, forming the sinus or bosom. This was deep enough to serve as a pocket for the reception of small articles. The part running from the left shoulder to the ground in front was pulled up over the sinus to fall in a loop a trifle to the front. This seems to have been the toga as worn by Caesar and Cicero. This might also be drawn over the right shoulder, as was the earlier form of the large toga. The early toga may well have been woven in one piece, but the larger forms must have been woven or cut in two sections, which were then sewed together. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“It will be clearly found in practice that much of the grace of the toga must have been due to the trained vestiplicus, who kept it properly creased when it was not in use and carefully arranged each fold after his master had put it on. We are not told of any pins or tapes to hold the toga in place,4 but are told that the part falling from the left shoulder toward the ground behind kept all in position by its own weight, and that this weight was sometimes increased by lead sewed in the hem of this part. |+|

“It is evident that in this fashionable toga the limbs were completely fettered, and that all rapid, not to say violent, motion was absolutely impossible. In other words the toga of the ultrafashionable in the time of Cicero was fit only for the formal, stately, ceremonial life of the city. It is easy to see, therefore, how it had come to be the emblem of peace, being too cumbrous for use in war, and how Cicero could sneer at the young dandies of his time for wearing “sails, not togas.” We can understand also the eagerness with which the Roman welcomed a respite from civic and social duties. Juvenal sighed for the freedom of the country, where only the dead had to wear the toga. For the same reason Martial praised the unconventionality of the provinces. Pliny the Younger counted it one of the attractions of his villa that no guest need wear the toga there. Its cost, too, made it all the more burdensome for the poor, and the working classes could scarcely have afforded to wear it at all. |+|

“For certain ceremonial observances the toga, or rather the sinus, was drawn over the head from the rear. The cinctus Gabinus was another manner of arranging the toga for certain sacrifices and official rites. For this the sinus was drawn over the head and then the long end which usually hung down the back from the left shoulder was drawn under the left arm and around the waist behind to the front and tucked in there.” |+|

Kinds of Togas

The toga of the ordinary citizen was, like the tunic, of the natural color of the white wool of which it was made, and varied in texture, of course, with the quality of the wool. It was called toga pura (or virilis, libera). A dazzling brilliancy could be given to the toga by a preparation of fuller’s chalk, and one so treated was called toga splendens or candida. In such a toga all persons running for office arrayed themselves, and from it they were called candidati. The curule magistrates, censors, and dictators wore the toga praetexta, differing from the ordinary toga only in having a “purple” (garnet) border. It was worn also by boys and by the chief officers of the free towns and colonies. In the early toga this border seems to have been woven or sewed on the curved edge. It was probably on the edge of the sinus in the later forms. The toga picta was wholly of crimson covered with embroidery of gold, and was worn by the victorious general in his triumphal procession, and later by the emperors. The toga pulla was simply a dingy toga worn by persons in mourning or threatened with some calamity, usually a reverse of political fortune. Persons assuming it were called sordidati and were said mutare vestem. This vestis mutatio was a common form of public demonstration of sympathy with a fallen leader. In this case curule magistrates contented themselves with merely laying aside the toga praetexta for the toga pura; only the lower orders wore the toga pulla. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The Lacerna. In Cicero’s time there was just coming into fashionable use a mantle called a lacerna, which seems to have been used first by soldiers and the lower classes and then adopted by their betters on account of its convenience. The better citizens wore it at first over the toga as a protection against dust and sudden showers. It was a woolen mantle, short, light, open at the side, without sleeves, but fastened with a brooch or buckle on the right shoulder. It was so easy and comfortable that it began to be worn not over the toga but instead of it, and so generally that Augustus issued an edict forbidding it to be used in public assemblages of citizens. Under the later emperors, however, it came into fashion again, and was the common outer garment at the theaters. It was made of various colors, dark, naturally, for the lower classes, white for formal occasions, but also of brighter hues. It was sometimes supplied with a hood (cucullus), which the wearer could pull over his head as a protection or a disguise. No representation in art of the lacerna that can be positively identified has come down to us. The military cloak, called at first trabea, then paludamentum and sagum, was much like the lacerna, but made of heavier material. |+|

“The Paenula. Older than the lacerna and used by all sorts and conditions of men was the paenula, a heavy coarse wrap of wool, leather, or fur, used merely for protection against rain or cold, and therefore never a substitute for the toga or made of fine materials or bright colors. It seems to have varied in length and fullness, but to have been a sleeveless wrap, made chiefly of one piece with a hole in the middle, through which the wearer thrust his head. It was, therefore, classed with the vestimenta clausa, or closed garments, and must have been much like the modern poncho. It was drawn on over the head, like a tunic or sweater, and covered the arms, leaving them much less freedom than the lacerna did. In the paenula of some length there was a slit in front running from the waist down, and this enabled the wearer to hitch the cloak up over one shoulder, leaving one arm comparatively free, but at the same time exposing it to the weather. The paenula was worn over either tunic or toga according to circumstances, and was the ordinary traveling habit of citizens of the better class. It was also commonly worn by slaves, and seems to have been furnished regularly to soldiers stationed in places where the climate was severe. Like the lacerna it was sometimes supplied with a hood.” |+|

Women Clothes in Ancient Rome

Women wore a long Ionic tunic made of linen with a girdle, or zona , around the waist. The tunic was made several centimeters too long and pulled up over the girdle, which gave it a skirt and blouse effect that remains with us today.

It has been remarked already that the dress of men and women differed less in ancient than in modern times, and we shall find that in the classical period at least the principal articles worn were practically the same, however much they differed in name and, probably, in the fineness of their materials. At this period the dress of the matron consisted in general of three articles: the tunica interior, the tunica exterior or stola, and the palla. Beneath the tunica interior there was nothing like the modern brassiere or corset, intended to modify the figure, but a band of soft leather (mamillare) was sometimes passed around the body under the breasts for a support, and the subligaculum was also worn by women. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

ancient Roman women's clothes

“The Tunica Interior. The tunica interior did not differ much in material or shape from the tunic for men already described. It fitted the figure more closely perhaps than the man’s, was sometimes supplied with sleeves, and as it reached only to the knee did not require a belt to keep it from interfering with the free use of the limbs. A soft sash-like band of leather (strophium), however, was sometimes worn over it, close under the breasts, but merely to support them; in this case, we may suppose, the mamillare was discarded. For this sash , the more general terms zona and cingulum are sometimes used. This tunic was not usually worn alone, even in the house, except by young girls. |+|

“The Stola. Over the tunica interior was worn the tunica exterior, or stola, the distinctive dress of the Roman matron. It differed in several respects from the tunic worn as a house-dress by men. It was open at both sides above the waist and fastened on the shoulders by brooches It was much longer, reaching to the feet when ungirded and having in addition a wide border (instita) on its lower edge. There was also a border around the neck, which seems to have been of some color, perhaps often crimson. The stola was sleeveless if the tunica interior had sleeves, but, if the tunic itself was sleeveless, the stola had sleeves, so that the arm was always protected. These sleeves, however, whether in tunic or in stola, were open on the front of the upper arm and were only loosely clasped with brooches or buttons, often of great beauty and value. |+|

“Owing to its great length the stola was always worn with a girdle (zona) above the hips; through this girdle the stola itself was pulled until the lower edge of the instita barely cleared the floor. This gave the fullness about the waist seen in Figures 24, 116, and 148, in which the cut of the sleeves can also be seen. The zona was usually entirely hidden by the overhanging folds. The stola was the distinctive dress of the matron, as has been said, and it is probable that the instita was its special feature. |+|

“The Palla. The palla was a shawl-like wrap for use out of doors. It was a rectangular piece of woolen goods, as simple as possible in its form, but worn in the most diverse fashions in different times. In the classical period it seems to have been wrapped around the figure, much as the toga was. One-third was thrown over the left shoulder from behind and allowed to fall to the feet. The rest was carried around the back and brought forward either over or under the right arm at the pleasure of the wearer. The end was then thrown back over the left shoulder after the style of the toga, as is shown in the relief from the Ara Pacis or was allowed to hang loosely over the left arm. It was possible also to pull the palla up over the head.” |+|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024