Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

NERO REBUILDS ROME AFTER THE GREAT FIRE

Nero's most lasting contribution was his rebuilding of Rome. Before the fire, Tacitus wrote, the great city was put together "indiscriminately and piecemeal." Afterwards, according to Nero's orders, Rome was rebuilt "in measured lines of streets, with broad thoroughfares, buildings of restricted height, and open spaces, while porticoes were added as protection to the front of the apartment-blocks...These porticoes Nero offered to erect at his own expense, and also to hand over his building sites, clear of rubbish, to the owners." He also established building codes that required new houses to be built with fire walls, and organized a fire department. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin] Tacitus wrote: “From the ashes of the fire rose a more spectacular Rome. A city made of marble and stone with wide streets, pedestrian arcades and ample supplies of water to quell any future blaze. The debris from the fire was used to fill the malaria-ridden marshes that had plagued the city for generations.

Narrow streets were widened, and more splendid buildings were erected. The vanity of the emperor was shown in the building of an enormous and meretricious palace, called the “golden house of Nero,” and also in the erection of a colossal statue of himself near the Palatine hill. To meet the expenses of these structures the provinces were obliged to contribute; and the cities and temples of Greece were plundered of their works of art to furnish the new buildings. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “In addition to the Gymnasium Neronis, the young emperor’s public building works included an amphitheater, a meat market, and a proposed canal that would connect Naples to Rome’s seaport at Ostia so as to bypass the unpredictable sea currents and ensure safe passage of the city’s food supply. Such undertakings cost money, which Roman emperors typically procured by raiding other countries. But Nero’s warless reign foreclosed this option. (Indeed, he had liberated Greece, declaring that the Greeks’ cultural contributions excused them from having to pay taxes to the empire.) Instead he elected to soak the rich with property taxes—and in the case of his great shipping canal, to seize their land altogether. The Senate refused to let him do so. Nero did what he could to circumvent the senators—“He would create these fake cases to bring some rich guy to trial and extract some heavy fine from him,” says Beste—but Nero was fast making enemies. One of them was his mother, Agrippina, who resented her loss of influence and therefore may have schemed to install her stepson, Britannicus, as the rightful heir to the throne. Another was his adviser Seneca, who was allegedly involved in a plot to kill Nero. By A.D. 65, mother, stepbrother, and consigliere had all been killed. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GREAT FIRE OF ROME IN A.D. 64: NERO, EVIDENCE, STORIES, RUMORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO (A.D. 37-68): HIS LIFE, DEATH, MOTHER AND WIVES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO (RULED A.D. 54-68) AS EMPEROR: EARLY PROMISE, REFORMS, LATER REVOLTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S CRUELTY — TOWARDS HIS FAMILY, AIDES AND CHRISTIANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO’S BUFFOONERY, EXTRAVAGANCE AND STRANGE SEX LIFE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Nero's Domus Aurea: Reconstruction and Reception of the Volta Dorata”

(2022) by Marco Brunetti Amazon.com;

“Domus Aurea” by Elisabetta Segala, Ida Sciortino, Colin Smith Amazon.com;

“The Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution” by Larry F. Ball (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Great Fire of Rome: Life and Death in the Ancient City”, Illustrated, by Joseph J. Walsh (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City” Amazon.com;

“Rome Is Burning: Nero and the Fire That Ended a Dynasty” by Anthony A. Barrett (2022) Amazon.com;

“Nero: The Man Behind the Myth” by Thorsten Opper (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nero” by John F. Drinkwater (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nero” by Edward Champlin (2003) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“Annals” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

Nero's Golden House

Nero's Golden House (in a park on Esquiline Hill near the Colosseum Metro station) is where Nero built a sprawling palace "worthy of his greatness" that once covered about a third of Rome. Nero's most monumental construction project. When it was completed, its is said, the whole city of Rome was invited inside. The palace was rediscovered in the 15th century when a young man fell into a hole in the ground and found himself in a richly decorated cave. It and its artwork became an inspiration for Michelangelo and Raphael as well as infamous tourists such as Casanova and the Marquis de Sade.

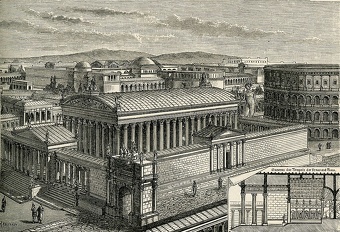

Built more for carousing and relaxing than to live in, the Golden House (Domus Aura) is a ruin today but in Nero's time it was a magnificent pleasure garden decorated with gold, ivory and mother-of-pearl and statues gathered from Greece. Buildings were connected by long columned colonnades and surrounded by a vast expanse of gardens, parks and forests stock with animals from the far corners of his empire. Built between A.D. 58 and 64, the huge property was located in the heart of imperial Rome and have sprawled across as many as 300 acres, though its true extent is difficult to determine. According to Archaeology magazine: The main villa of the complex has more than 300 rooms, including an octagonal dining room with a revolving domed roof, walls inlaid with jewels and gold, ceilings covered in mosaics, and brightly colored frescoes on nearly every wall and vaulted ceiling. [Source: Marco Merola, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2014]

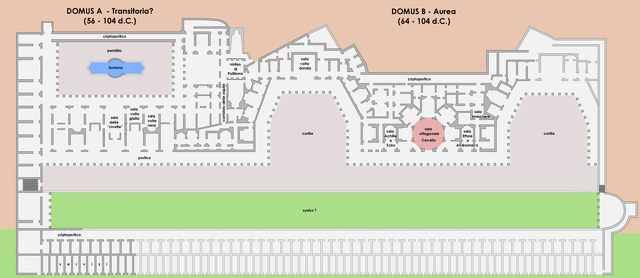

Federico Gurgone wrote in Archaeology magazine: In no other matter did he act more wasteful than in building a house that stretched from the Palatine to the Esquiline Hill, which he originally named “Transitoria” [House of Passages], but when soon afterwards it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt he called it “Aurea” [Golden House]. A house whose size and elegance these details should be sufficient to relate: Its courtyard was so large that a 120-foot colossal statue of the emperor himself stood there; it was so spacious that it had a mile-long triple portico; also there was a pool of water like a sea, that was surrounded by buildings which gave it the appearance of cities; and besides that, various rural tracts of land with vineyards, cornfields, pastures, and forests, teeming with every kind of animal both wild and domesticated. In other parts of the house, everything was covered in gold and adorned with jewels and mother-of-pearl; dining rooms with fretted ceilings whose ivory panels could be turned so that flowers or perfumes from pipes were sprinkled down from above; the main hall of the dining rooms was round, and it would turn constantly day and night like the Heavens; there were baths, flowing with seawater and with the sulfur springs of the Albula; when he dedicated this house, that had been completed in this manner, he approved of it only so much as to say that he could finally begin to live like a human being. Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars. [Source: Federico Gurgone, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

“In the mid-first century A.D. there was no building in Rome as sumptuous, ornate, or grand as the Domus Aurea, or “Golden House,” a lavish imperial residence and sprawling park covering hundreds of acres in an area known as the Oppian Hill between the Palatine and Esquiline Hills on the city’s northern side. Constructed by the emperor Nero and born from the ashes of the massive A.D. 64 fire that destroyed the city center and cleared the space that it would occupy — perhaps explaining the persistent suspicion held by many Romans that the emperor himself had set the fire — the vast property had hundreds of rooms. There were walls sheathed in polychrome marble, vaults and ceilings covered in vibrant frescoes by the artist Fabullus, and in precious stones, ivory, and gold, and gardens full of masterpieces of sculpture from Greece and Asia Minor. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, who praises the palace’s architects, Severus and Celer, for having the “ingenuity and courage to try the force of art even against the veto of nature,” what was even more marvelous than the spectacular interiors were “the fields and lakes and the air of solitude given by wooden ground alternating with clear tracts and open landscapes." Yet the emperor’s extraordinary palace was never finished, and it stood for only four years

Parts of Nero's Golden House

The main palace was built overlooking an artificial lake made by flooding the area where the Colosseum now stands; Caellian Hill was the site of his private garden; and the Forum was made into a wing of the palace. A 35-foot-high colossus of Nero, the largest bronze statue ever made, was erected. The palace was encrusted in pearls and covered with ivory,

"Its vestibule," wrote Suetonius, “was large enough to contain a colossal statue of the Emperor a hundred and twenty feet height: and it was so extensive that it had a triple portico a mile long. There was a pond too, like a sea, surrounded with buildings to represent cities; besides tracts of country, varied by tilled fields, vineyards, pastures and woods, with great numbers of wild and domesticated animals.”

"In the rest of the palace all parts were overlaid with gold and adorned with gems and mother-of-pearl. There were dining rooms with fretted ceilings of ivory, whose panels could turn and shower down flowers, and were fitted with pipes for sprinkling the guests with perfumes. The main banquet hall was circular and constantly revolving night and day, like the heavens...When the palace was finished...he dedicated it...to say...at last he was beginning to be housed as a human being."

The Golden House was surrounded by a vast country estate right in the middle of Rome that was laid out like a stage, with woodlands and lakes and promenades accessible to all. Some scholars say that Suetonius only hinted at it splendor. Nero revisionist Ranieri Panetta told National Geographic, “it was a scandal, because there was so much Rome for one person. It wasn’t only that it was luxurious—there had been palaces all over Rome for centuries. It was the sheer size of it. There was graffiti: ‘Romans, there’s no more room for you, you have to go to [the nearby village of] Veio.’” For all its openness, what the Domus ultimately expressed was one man’s limitless power, right down to the materials used to construct it. “The idea of using so much marble was not just a show of wealth,” Irene Bragantini, an expert on Roman paintings, told National Geographic. “All of this colored marble came from the rest of the empire—from Asia Minor and Africa and Greece. The idea is that you’re controlling not just the people but also their resources. In my reconstruction, what happened in Nero’s time is that for the first time, there’s a big gap between the middle and upper class, because only the emperor has the power to give you marble.” [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

The Domus Aurea is located between the Palatinum, Caelius and Oppius hills of Rome (the Colosseum was built later in the central area by the Flavian emperors); On the map are shown: 1) Domus Augusti, Domus Tiberiana and Domus Neronis? (houses of the emperors) on the Palatine hill; 2) the Templum divi Claudi (temple for emperor Claudius), Nymphaeum Neronis (temple for a local nymph by Nero, fountain) and another Nymphaeum? on the Caelius hill; 3) Thermae Neronis? (public bath of Nero), Domus aurea (Oppius) (part of the Domus Aurea), Domus Selani (house of Selanus) and Hortus Maecenatis (Garden of Maecenas); and 4) the large statue of Nero Colussus Neronis in the Domus Aurea (Vestibulum) and the large pool of the Domus Aurea (Stagnum) in the center

Stunning Features of Nero’s Golden House

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Nero’s palace was known as the “Golden House” because of the use of gold leaf throughout, and the jewels that adorned the ceilings inside. The palace was carefully and intricately landscaped and covered in white marble. It was built over the remains of several aristocratic villas that had been destroyed in the Great Fire of Rome. The Roman biographer Suetonius tells us that the palace was “ruinously prodigal” and included pastures, flocks of animals, vineyards, trees, and even an artificial lake, all of which were in the center of the city. According to another historian, Tacitus, Nero oversaw the engineering of the palace himself. Remarkably, the entire thing was constructed in only five years. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 25, 2019]

There were numerous innovations in the design of the building, but perhaps the most extraordinary was a mechanism, operated by slaves, that caused a domed ceiling to revolve and drop perfume and rose petals onto assembled party guests as they ate. If it sounds like this would obscure the smell of the food then that was the point. As Mark Bradley has written in Smell and the Ancient Senses, aristocratic Romans like to keep their guests in suspense about the contents of their meals. It was considered especially low-brow to be drawn to the smell of a meal cooking in the kitchen. The device wasn’t a resounding success — according to one story, likely influenced by the propaganda of his opponents, one dinner guest was asphyxiated.

The whole design was so ornate that Nero placed mosaics, which were previously found on floors, on the ceilings of the rooms. The technique would set a trend, especially in the design of Christian churches in Rome, Ravenna, and Constantinople. If you have ever been awed by the mosaics at San Apollinaire Nuovo in Ravenna, you have Nero’s decadent taste to thank. Which is somewhat ironic given Nero’s reputation as the Antichrist and persecutor of Christians.

Arguably the most remarkable thing about this sprawling, decadent, and wildly over the top palace was that it included neither bedrooms, nor bathrooms. There wasn’t even a kitchen. In an interview in 1999 around the opening of the Domus Aurea to the public, the noted historian Andrew Wallace-Hadrill noted that the palace was purely for entertaining, saying, “Nero gave the best parties, ever.” If you don’t mind doing your business in a chamber pot, that is.

Decorations and Artwork in the Golden House

The extensive use of gold leaf that gave the palace its name was only one part of extravagant decor: stuccoed ceilings were faced with semi-precious stones and ivory veneers, while the walls were frescoed, coordinating the decoration into different themes in each major group of rooms. Pliny the Elder observed it being built and mentions it in his Naturalis Historia. Unfortunately, only fragments of the mosaics placed on the vaulted ceilings survive.

In the Golden House there are a number high-vaulted galleries. Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Splendid frescoes line some of the walls, in a style we recognize from the ruins at Pompeii — but the distinctive aesthetic, later expressed across the Roman Empire, originated here, at the Domus Aurea. In one room the walls are surfaced with roughly textured pumice, recreating a natural grotto. The space was dedicated to the nymphs, or female nature deities, whose cult of worship had spread throughout the empire. A micro-mosaic adorns the ceiling: It depicts in astonishing detail a scene from the Odyssey. The ceiling mosaic surely influenced the Byzantines, who later plastered ceiling mosaics almost everywhere. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

Frescoes covered every surface that was not more richly finished. The main artist was Famulus (or Fabulus, or Amulius according to some sources). Fresco technique, working on damp plaster, demands a speedy and sure touch: Famulus and assistants from his studio covered a spectacular amount of wall area with frescoes. Pliny recounts how Famulus went for only a few hours each day to the Golden House, to work while the light was best. He wore a toga (the sign that he was a citizen) even when painting on scaffolding. Pliny said that because Famulus spent so much time at the Golden House, very little of his artwork was to be found elsewhere.

Pliny wrote: More recently, lived Amulius, a grave and serious personage, but a painter in the florid style. By this artist there was a Minerva, which had the appearance of always looking at the spectators, from whatever point it was viewed. He only painted a few hours each day, and then with the greatest gravity, for he always kept the toga on, even when in the midst of his implements. The Golden Palace of Nero was the prison-house of this artist's productions, and hence it is that there are so few of them to be seen elsewhere. The murals are likely to be the work of an artist named Famulus, one of the few named and identifiable artists of antiquity.

In May 2019, archaeologists announced the discovery of a chamber nicknamed the “sphinx room” that was part of Nero’s Golden Place under the Colosseum in Rome. The room featured a number of murals. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The discovery of these new murals, Alfonsina Russo, director of the archaeological park of the Colosseum, said can tell us more about the cultural atmosphere of Nero’s age. Much of the room is still filled with dirt and debris, but in addition to the Sphinx, the room is also adorned with images of a centaur, Pan (the half-goat god), and a man armed with a sword being attacked by a panther.

Was the Golden House a House for the People?

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The Domus Aurea’s boldest artistic innovation was surely its architecture. We know little of the two men who designed it — Severus and Celer. D’Alessio thinks Nero himself must have stayed closely involved in this grand-scale project. After all, this is the kind of thing, not ruling Rome, that turned him on. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

“High overhead, an open hole, or oculus, invited the sky in. Rome’s Pantheon uses the same device to magnificent effect, but Nero’s Octagonal Room did it first. Alcoves radiated off the main space underneath, inviting the eye to wander in unexpected directions. Precisely angled windows channeled sunlight to hidden niches. Light and shadow danced around the room, following the course of the sun. “Pure genius,” says D’Alessio. “The Sala Octagonale is very significant for Roman architecture, but also for the development of Byzantine and Islamic architecture. It is a very important place for Western civilization. Nero left us masterpieces. We have a certain image of Nero from the ancient sources who were against Nero, and also, in our time, from the movies. The Church chose Nero as the representation of evil, but if you see what he made here, you get a completely different idea.”

The Domus Aurea project was also a mistake, criticized in its day as a lot more house than any absolute monarch would ever need. But it may be that Nero never meant for this city-within-a-city to be his purely private playground. “The Emperor wanted to make its pleasures available to the people,” David Shotter, a historian, asserts in his 2008 biography of Nero. “Recent excavations near the Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum have revealed a colonnaded pool, the stagnum Neronis, which imitated Nero’s lake at Baiae and the stagnum Agrippae on the Campus Martius.

The implication of this appears to be that Nero intended that his new house and the rebuilt city of Rome should be one — the home of the people and of himself, their Emperor, Protector and Entertainer.” Shotter goes on, “those looking for signs of Nero’s supposed madness will not find it here; his contribution to Roman construction should not be dismissed or underestimated in the shallow manner of many of his contemporaries. Here, writ large, is Nero the artist and popular provider — almost certainly the way in which he would have wished to be remembered.”

Golden House After Nero

The House of Gold stood for 36 years after Nero’s suicide when it was destroyed by fire in A.D. 104. Soon after his death it was was stripped of its ivory, jewels and marble. The emperor Vespasian built the Colosseum, over the artificial lake. And the Emperor Trajan covered much of the palace with the Baths of Trajan. Succeeding emperors erected their own temples and palaces, filled in his ponds that were "like the sea". Marble and statuary was hauled away with elephants to decorate the Colosseum. According to legend, the emperors kept the statues and replaced the heads with likenesses of themselves. The frescoed halls, today mostly underground, were preserved thanks to Emperor Trajan, who buried the palaces in the process of using it as a foundation for his bath complex.

Federico Gurgone wrote in Archaeology magazine: It was not until the late fifteenth century, when a boy fell through an opening in the side of the hill, that the palace’s decoration became well known. Some of the greatest Italian painters, among them Pinturicchio, Ghirlandaio, and Raphael, were lowered by ropes into openings that were originally believed to be caves. Instead, they saw what became the main source of knowledge of the ancient Roman styles of painting that would so heavily influence the art and architecture of the Renaissance.[Source: Federico Gurgone, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

In the eighteenth century, vineyards covered the Oppian Hill, and in 1871, a large public park incorporating the ruins of the ancient baths was created there. The park was then enlarged during Mussolini’s reign and served as a backdrop for the opening of the newly renovated area around the Colosseum in 1936. The Domus Aurea was closed since 2005 for safety reasons — and a ceiling vault collapsed in 2010. Persistent problems with drainage and moisture threaten both its structural stability and its decorations. In the 2010s, the archaeological superintendency of Rome embarked on the last phase of an ambitious restoration project.[Source: Marco Merola, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2014]

The first priority has been to completely rethink and redesign the park, which is in terrible condition. “Until we have lightened the volume of the park — whose weight increases by up to 30 percent when it rains — by more than half, we are far from any effective solution,” says Fedora Filippi, the archaeologist responsible for the Domus Aurea excavations. “We have had to map and then remove existing trees that are causing the most damage, while documenting the entire excavation phase in detail,” she says. “We can’t just dismantle the garden without taking precautions or we will destroy the palace’s frescoed walls, which have managed to adapt and stay standing over the centuries.”

“Filippi explains that the existing garden will be replaced at a level more than 10 feet above where it is now, with a subsurface infrastructure designed to seal off the underground architecture from moisture and regulate temperature and humidity. The new garden will also have walkways that will recall the past, says Strano. “The ancient writers Columella and Pliny tell us that Roman gardens were made up of straight avenues crossed at right angles by little paths. These new lines will also suggest to visitors the outlines of the structures underneath, and make it possible to channel rainwater.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Golden House of an Emperor”, Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Nero's Theater Discovered near the Vatican

In July 2023, archaeologists announced that had discovered the ruins of Nero’s Theater, an imperial theater referred to in ancient Roman texts but never found, under the garden of a future Four Seasons Hotel near the Vatican. Associated Press reported: Archaeologists have excavated deep under the walled garden of the Palazzo della Rovere since 2020 as part of planned renovations on the frescoed Renaissance building. The palazzo, which takes up a city block along the broad Via della Conciliazione leading to St. Peter’s Square. [Source: Nicole Winfield, Associated Press, July 26, 2023]

Archaeologists found marble columns and gold-leaf decorated plaster, leading them to conclude that the Nero's Theater referred to in texts by Pliny the Elder, was indeed there, located at the site just off the Tiber River.Officials said the portable antiquities would be moved to a museum, while the ruins of the theater structure itself would be covered again after all studies are completed.

Archaeology magazine reported: According to several ancient Roman authors, one of Nero’s favorite venues in which to stretch his vocal cords was a private theater he built in the Gardens of Agrippina, a luxurious villa that belonged to his mother in the Roman neighborhood near the Vatican now called Vaticano. Nero’s theater is known from literary sources — the Roman historian Tacitus may have been referring to this building when he wrote about the emperor singing of the fall of Troy as he watched Rome burn in July of A.D. 64. The structure was largely dismantled for materials in antiquity and its precise location was unknown until archaeologists unearthed its remnants in a Renaissance garden. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2024

The impressive ruins include the theater’s cavea, a 138-foot-wide semicircular seating area, and a rectangular space with entrances and stairways. Another building may have been used to store sets and costumes. Both structures were built of bricks dating to the period of the Julio-Claudian emperors (27 B.C.– A.D. 68), in particular Caligula (reigned A.D. 37–41) and Nero. The theater was just one part of the self-aggrandizing building campaign Nero undertook across the city, which included construction of the Domus Aurea, or Golden House, which served as his monstrous private pleasure palace. Like the Domus Aurea, Nero’s theater was decorated with marble columns in white and a variety of colors as well as gold-covered stucco, many examples of which were unearthed. “This discovery has the double value of confirming the existence of a brick theater in the Gardens of Agrippina,” says archaeologist Marzia Di Mento, who works with the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome, “and of finding its precise location.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024