Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

AWFUL THINGS NERO ALLEGEDLY DID

Poppea, Nero's second wife, bringing the head of Octavia, his first wife, to Nero

Nero (A.D. 37-68) was the fifth emperor of Rome, ruling from A.D. 54 to 68. He became the Roman emperor when he was seventeen, the youngest ever at that time. Nero's real name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He is known mainly for being a cruel wacko but in many ways he left the Roman Empire better off than when arrived.

In his book “Nero,” Edward Champlin wrote: “Nero murdered his mother, and Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Nero also slept with his mother, Nero married and executed one stepsister, executed his other stepsister, raped and murdered his stepbrother. In fact, he executed or murdered most of his close relatives. He kicked his pregnant wife to death. He castrated and then married a freedman. He married another freedman, this time himself playing the bride. He raped a vestal virgin. He melted down the household gods of Rome for their cash value."

“After incinerating the city in 64, he built over much of downtown Rome with his own great Xanadu, the Golden House. He fixed the blame for the Great Fire on the Christians, some of whom he hung up as human torches to light his gardens at night. He competed as a poet, singer an actor, a herald and charioteer, and he won every contest, even when he fell out of his chariot at the Olympics games, he alienated and persecuted the elite, neglected the army, and drained the treasury. And he committed suicide at the age of 30, one step ahead of his executioners. His last words were, “What an artist died in me!”

Nero’s worst enemies were in his own family and household. The intrigues of his unscrupulous and ambitious mother, Agrippina, to displace Nero and elevate Britannicus, the son of Claudius, led to Nero’s first domestic tragedy—the poisoning of Britannicus. He afterward yielded himself to the influence of the infamous Poppaea Sabina, said to be the most beautiful and the wickedest woman of Rome. At her suggestion, he first murdered his mother, and then his wife. He discarded the counsels of Seneca and Burrhus, and accepted those of Tigellinus, described a man of the worst character. Then followed a career of wickedness, extortion, and atrocious cruelty. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Patrick Ryan wrote in Listverse, Nero “ murdered thousands of people including his aunt, stepsister, ex-wife, mother, wife and stepbrother. Some were killed in searing hot baths. He poisoned, beheaded, stabbed, burned, boiled, crucified and impaled people. He often raped women and cut off the veins and private parts of both men and women. Thousands of Christians were starved to death, burned, torn by dogs, fed to lions, crucified, used as torches and nailed to crosses. He was so bad that many of the Christians thought he was the Antichrist. He even tortured and killed the apostle Paul and the disciple Peter. Paul was beheaded and Peter was crucified upside down.” [Source: Patrick Ryan, Listverse, May 30, 2012]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “He instructed his mentor Seneca to commit suicide (which he solemnly did); castrated and then married a teenage boy; presided over the wholesale arson of Rome in A.D. 64 and then shifted the blame to a host of Christians (including Saints Peter and Paul), who were rounded up and beheaded or crucified and set aflame so as to illuminate an imperial festival. The case against Nero as evil incarnate would appear to be open and shut.” [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NERO (A.D. 37-68): HIS LIFE, DEATH, MOTHER AND WIVES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO (RULED A.D. 54-68) AS EMPEROR: EARLY PROMISE, REFORMS, LATER REVOLTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

GREAT FIRE OF ROME IN A.D. 64: NERO, EVIDENCE, STORIES, RUMORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S GOLDEN HOUSE AND THE REBUILDING ROME AFTER THE GREAT FIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO’S BUFFOONERY, EXTRAVAGANCE AND STRANGE SEX LIFE factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Nero: The Man Behind the Myth” by Thorsten Opper (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nero” by John F. Drinkwater (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nero” by Edward Champlin (2003) Amazon.com;

“Nero: Matricide, Music, and Murder in Imperial Rome” by Anthony Everitt and Roddy Ashworth (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evil Roman Emperors: The Shocking History of Ancient Rome's Most Wicked Rulers from Caligula to Nero and More by Phillip Barlag (2021) Amazon.com;

“Infamous Roman Emperors: Conquest, Sabotage, and Betrayal in the Roman Empire” by August Mead (2023) Amazon.com;

“From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68" by H.H. Scullard Amazon.com;

“Nero's Killing Machine” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2005) Amazon.com

“The Neronian Grotesque” by Scott Weiss (2023) Amazon.com

“Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World” by Emma Southon (2020) Amazon.com;

“Agrippina: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Early Empire” by Anthony A. Barrett (1999)

Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“Annals” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Did Nero Get a Bad Rap?

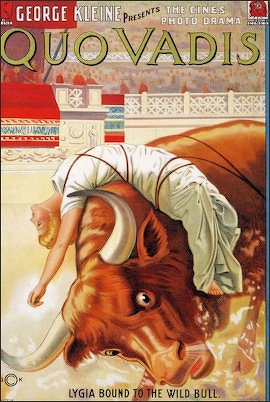

Lygia tied to the wild bull, from Quo Vadis, a 1913 movie about Nero

Now some scholars say Nero wasn’t all bad. After describing his alleged crimes, Champlin spends much of the rest of his book examining whether Nero was indeed the monster he was made out to be. He points out the stories of Nero's legendary exploits come mainly from the work of three writers — the historians Tacitus and L. Casius Dio and the biographer Suetonius — whose own sources appear to have been hearsay, public record long since lost and the works of “several lost authors," including Pliny the Elder and Cluvius Rufus. The accounts of the three writers are often inconsistent and sometime contradictory.

Champlin said he was not out to “whitewash” Nero: “He was a bad man and a bad ruler. But there is strong evidence to suggest that our dominant sources have misrepresented him badly, creating the image of the unbalanced, egomaniacal monster, vividly enhanced by Christian writers, that has so dominated the shocked imagination of the Western tradition for two millennia, The reality was more complex."

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “The dead do not write their own history. Nero’s first two biographers, Suetonius and Tacitus, had ties to the elite Senate and would memorialize his reign with lavish contempt. The notion of Nero’s return took on malevolent overtones in Christian literature, with Isaiah’s warning of the coming Antichrist: “He will descend from his firmament in the form of a man, a king of iniquity, a murderer of his mother.” Later would come the melodramatic condemnations: the comic Ettore Petrolini’s Nero as babbling lunatic, Peter Ustinov’s Nero as the cowardly murderer, and the garishly enduring tableau of Nero fiddling while Rome burns. What occurred over time was hardly erasure but instead demonization. A ruler of baffling complexity was now simply a beast. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

Admired Emperors did the same kind of things or even worse. ““Today we condemn his behavior,” says archaeological journalist Marisa Ranieri Panetta. “But look at the great Christian emperor Constantine. He had his first son, his second wife, and his father-in-law all murdered. One can’t be a saint and the other a devil. Look at Augustus, who destroyed a ruling class with his blacklists. Rome ran in rivers of blood, but Augustus was able to launch effective propaganda for everything he did. He understood the media. And so Augustus was great, they say. Not to suggest that Nero was himself a great emperor—but that he was better than they said he was, and no worse than those who came before and after him.” ~

Nero’s Defenders

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“A few lonely voices have come to Nero’s defense. In 1562, the Milanese polymath Girolamo Cardano published a treatise, Neronis Encomium. He argued that Nero had been slandered by his principal accusers. But Cardano was having his own problems with the Inquisition at the time. Sticking up for a guy who, among other things, supposedly martyred the first Christians for fun was not likely to help his own cause. “You put your life at risk if you said something good about Nero,” says Angelo Paratico, a historian, who translated Cardano’s manifesto into English. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

Paratico’s translation, Nero, An Exemplary Life, didn’t appear until 2012, by which time historians had started taking another look at the case against Nero. Out of all the modern scholars coming to the emperor’s rescue, the most comprehensive is John Drinkwater, an emeritus professor of Roman history at the University of Nottingham. Drinkwater has spent 12 years poring over the charges against Nero, and dismantling them one by one. Scourge of Christianity? Nope. Urban pyromaniac? No again. And on down through matricide, wife-killing and a string of other high crimes and misdemeanors.

“The Nero who appears in Drinkwater’s revisionist new account, Nero: Emperor and Court, published in 2019 is no angel. But one comes away with some sympathy for this needy lightweight who probably never wanted to be emperor in the first place and should never have been allowed to wear the purple toga. Drinkwater is in line with the emerging trend of modern scholarship here, but he goes much further. Nero allowed a ruling clique to administer the Roman Empire, and it did so effectively, argues Drinkwater. Most of what Nero is accused of doing, he probably didn’t do, with a few exceptions that fall well within the grisly standards of ancient Roman political machinations. Drinkwater’s Nero bears little personal responsibility, and not much guilt, for much of anything. In the end, says Drinkwater, the “men in suits” got rid of Nero not for what he did, but for what he failed to act on. (On the other hand, Drinkwater believes that Nero probably crooned a few stanzas during the Great Fire, but we’ll get to that later.)

“Drinkwater says many modern scholars have been trying to explain why Nero was so awful — “that he was a young man put in the wrong job and therefore he went to the bad. He was tyrannical not because he was evil, but because he couldn’t do the job. That’s more or less what I expected too. I was surprised because my Nero was not coming out like this. My Nero was not the out-and-out evil tyrant, because he was never really in control. Nobody here is tyrannical.”

Nero's Cruelty and Wantonness

Nero at the Circus

When Nero was 25, after reigning for fiver years, his personality changed dramatically and he turned into a fiend and a ruthless killer. He murdered his brother, his pregnant wife, and his mother who he had tried to assassinate five times before finally achieving success. Nero continued down this ruthless and murderous path for the rest of his short life. He forced his successful generals to commit suicide and tortured and executed suspected plotters. His tutor Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 B.C." 65 AD), who had dominated Nero's court, was forced to commit suicide at Nero's command. Some have blamed Nero despicable behavior on his childhood. After his father died he was brought up in the home of his deranged uncle Caligula and raised by his "impetuous and deranged mother"Agrippina the Younger, who used "incest and murder" to secure him the throne over the rightful heir and eliminated rivals in her son's path to the emperorship by poisoning their food, it is said, with a toxin extracted from a shell-less mollusk known as a sea hare.

Suetonius wrote: “Although at first his acts of wantonness, lust, extravagance, avarice and cruelty were gradual and secret, and might be condoned as follies of youth, yet even then their nature was such that no one doubted that they were defects of his character and not due to his time of life. No sooner was twilight over than he would catch up a cap or a wig and go to the taverns or range about the streets playing pranks, which however were very far from harmless; for he used to beat men as they came home from dinner, stabbing any who resisted him and throwing them into the sewers. He would even break into shops and rob them, setting up a market in the Palace, where he divided the booty which he took, sold it at auction, and then squandered the proceeds. In the strife which resulted he often ran the risk of losing his eyes or even his life, for he was beaten almost to death by a man of the senatorial order whose wife he had maltreated. Warned by this, he never afterwards ventured to appear in public at that hour without having tribunes follow him at a distance and unobserved. Even in the daytime he would be carried privately to the theater in a litter, and from the upper part of the proscenium would watch the brawls of the pantomimic actors and egg them on; and when they came to blows and fought with stones and broken benches, he himself threw many missiles at the people and even broke a praetor's head. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“Little by little, however, as his vices grew stronger, he dropped jesting and secrecy and with no attempt at disguise openly broke out into worse crime. He prolonged his revels from midday to midnight, often livening himself by a warm plunge, or, if it were summer, into water cooled with snow. Sometimes, too, he closed the inlets and banqueted in public in the great tank in the Campus Martius, or in the Circus Maximus, waited on by harlots and dancing girls from all over the city. Whenever he drifted down the Tiber to Ostia, or sailed about the Gulf of Baiae, booths were set up at intervals along the banks and shores, fitted out for debauchery, while bartering matrons played the part of inn-keepers and from every hand solicited him to come ashore. He also levied dinners on his friends, one of whom spent four million sesterces for a banquet at which turbans were distributed, and another a considerably larger sum for a rose dinner.

Nero’s Kills Off His Family

The fate of Nero’s family was not good. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Nero ordered the murder of his mother, who had formerly been his chief adviser; had his ex-wife Octavia brutally murdered; allegedly kicked his pregnant second wife Poppaea to death in a fit of rage; and is said to have married a boy named Sporus. The likely enslaved Sporus apparently resembled Poppaea, whom Nero regretted killing. According to Suetonius, Nero had him castrated and married him in a traditional wedding ceremony complete with a veil and dowry. After that, Sporus appeared in public in the regalia of an empress and was allegedly addressed as “empress,” “lady,” or even “Poppaea.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 24, 2022]

Suetonius wrote: “He began his career of parricide and murder with Claudius, for even if he was not the instigator of the emperor's death, he was at least privy to it, as he openly admitted; for he used afterwards to laud mushrooms, the vehicle in which the poison was administered to Claudius, as "the food of the gods, as the Greek proverb has it." At any rate, after Claudius' death he vented on him every kind of insult, in act and word, charging him now with folly and now with cruelty; for it was a favorite joke of his to say that Claudius had ceased "to play the fool among mortals," lengthening the first syllable of the word morari, and he disregarded many of his decrees and acts as the work of a madman and a dotard. Finally, he neglected to enclose the place where his body was burned except with a low and mean wall. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Locusta testing a poison

“He attempted the life of Britannicus by poison, not less from jealousy of his voice (for it was more agreeable than his own) than from fear that he might sometime win a higher place than himself in the people's regard because of the memory of his father. He procured the potion from an arch-poisoner, one Locusta, and when the effect was slower than he anticipated, merely physicking Britannicus, he called the woman to him and flogged her with his own hand, charging that she had administered a medicine instead of a poison; and when she said in excuse that she had given a smaller dose to shield him from the odium of the crime, he replied: "It's likely that I am afraid of the Julian law;" and he forced her to mix as swift and instant a potion as she knew how in his own room before his very eyes. Then he tried it on a kid, and as the animal lingered for five hours, had the mixture steeped again and again and threw some of it before a pig. The beast instantly fell dead, whereupon he ordered that the poison be taken to the dining-room and given to Britannicus. The boy dropped dead at the very first taste, but Nero lied to his guests and declared that he was seized with the falling sickness, to which he was subject, and the next day had him hastily and unceremoniously buried in a pouring rain. He rewarded Locusta for her eminent services with a full pardon and large estates in the country, and actually sent her pupils.

Is Agrippina, Nero’s Mother, to Blame For His Bad Rap

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“The blame for saddling Nero with his unwanted destiny falls squarely on his mother,Agrippina the Younger, great-granddaughter of the emperor Augustus and a woman of boundless ambition. (Nero’s father, an odious aristocrat, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, died two years after Nero was born.) Nero became Agrippina’s instrument for conquering the man’s world of Rome. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

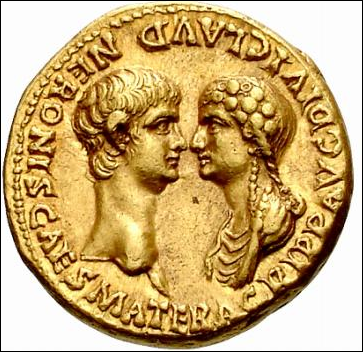

Nero and Agrippina “She moved first to disrupt the planned nuptials of the emperor’s daughter Octavia, so that Nero could marry her. The emperor at the time was Claudius, easily swayed. Agrippina’s improbable little lie — that Octavia’s fiancé had committed incest with his sister — proved toxic enough to torpedo the wedding. Readers of Robert Graves’ picaresque and hugely popular Claudius novels are unlikely to forget the sexual gymnastics of Messalina, Claudius’ notorious wife. In the end, Messalina’s antics brought her down, leaving a vacancy in the marriage bed that Agrippina filled in A.D. 49. Shortly thereafter, Claudius adopted Nero as his own son, making Nero a legitimate claimant to the throne, alongside Claudius’ natural son Britannicus. And finally, in A.D. 53, Nero married Octavia. The stage was set. Agrippina had managed everything with steely efficiency.

The Roman historian Tacitus is not always reliable and he is certainly not unbiased, but his portrait of Agrippina in her hour of triumph feels right today: “From this moment the country was transformed. Complete obedience was accorded to a woman — and not a woman like Messalina who toyed with national affairs to satisfy her appetites. This was a rigorous, almost masculine despotism.”

“More power to her, says Drinkwater, who is a big fan. “I think the Roman Empire lost out by not having Empress Agrippina. Given half the chance, I think she could have been another Catherine the Great. I admire her intelligence, her perspicacity. She was one of the few people who knew how the system worked. For example, Claudius is often reproached for killing a lot of senators, and he did, but when Agrippina comes along, you get very little of that. The modern thinking is that she worked well with the senate. If she had been given more time, she might have been able to establish a precedent of an active executive woman in Roman politics.”

“Claudius died in A.D. 54 after eating a mushroom that was either bad or poisoned — Tacitus and the ancients say poisoned on Agrippina’s orders, and while there’s no hard proof, nobody then or now would put it past her. In either case, Agrippina had greased the succession machine so that Nero, just 17, slid smoothly onto the throne following Claudius’ death, past the slightly younger Britannicus.

Incest of Agrippina and Nero

Tacitus wrote: “The author Cluvius writes that Agrippina took her desire to keep power so far as to offer herself more often to a drunken Nero, all dressed up and ready for incest. She did this at midday when Nero was already warmed up with wine and food. Those close to both had seen passionate kisses and sensual caresses, which seemed to imply wrongdoing. It was then that Seneca who looked for a woman’s help against this woman’s charms, introduced Acte to Nero. This freedwoman who was anxious because of the danger to herself and the damage to Nero’s reputation, told Nero that the incest was well known since Agrippina boasted about it. She added that the soldiers would not tolerate the rule of such a wicked emperor. [Source: Tacitus (b.56/57-after 117 A.D.): “Annals” Murder of Agrippina. Book 14, Chapters 1-12 , John D Clare's History Blog, johndclare.net/AncientHistory/Agrippina

“Cluvius relates that Agrippina in her eagerness to retain her influence went so far that more than once at midday, when Nero, even at that hour, was flushed with wine and feasting, she presented herself attractively attired to her half intoxicated son and offered him her person, and that when kinsfolk observed wanton kisses and caresses, portending infamy, it was Seneca who sought a female's aid against a woman's fascinations, and hurried in Acte, the freed-girl, who alarmed at her own peril and at Nero's disgrace, told him that the incest was notorious, as his mother boasted of it, and that the soldiers would never endure the rule of an impious sovereign.

“Fabius Rusticus writes that it was not Agrippina, but Nero, who was eager for incest, and that the clever action of the same freedwoman prevented it. A number of other authors agree with Cluvius and general opinion follows this view. Possibly Agrippina really planned such a great wickedness, perhaps because the consideration of a new act of lust seemed more believable in a woman who as a girl had allowed herself to be seduced by Lepidus in the hope of gaining power; this same desire had led her to lower herself so far as to become the lover of Pallas, and had trained herself for any evil act by her marriage to her uncle.

“No one doubted that he wanted sexual relations with his own mother, and was prevented by her enemies, afraid that this ruthless and powerful woman would become too strong with this sort of special favour. What added to this opinion was that he included among his mistresses a certain prostitute who they said looked very like Agrippina. They also say that, whenever he rode in a litter with his mother, the stains on his clothes afterwards proved that he had indulged in incest with her.

Murder of Agrippina

Agrippina's deathCambridge classic professor Mary Beard told an interviewer that Tacitus's account of Agrippina murder in “The Annals” is some of the best history ever written. “There is no better story than Nero's attempts to murder his mother with whom he is finally very pissed off! Nero the mad boy emperor decides that he is going to get rid of mum by a rather clever collapsible boat. He has her to dinner, waves her fondly farewell. The boat collapses. Sadly for Nero, his mum, Agrippina, is a very strong swimmer and she makes it to the land and back home. And she's clever, she knows boats don't just collapse like that — it was a completely calm night, so she works out Nero was out to get her. She knows things are going to end badly. Nero can't let her off, so he sends round the tough guys to murder her. Agrippina looks them in the eye and says, “Strike me in the belly with your sword." There are two things going on. One is: my son who came out of my belly is trying to murder me. But the other thing we know is that they were widely reputed to have had an incestuous relationship in the earlier days. So it's not just Nero the son murdering his mother, but Nero the lover murdering his discarded mistress. And if you read Robert Graves's I, Claudius, some of it comes directly from this." When asked if Tacitus's account is better than a Hollywood plot, Beard said, “Yes but it's not just that. What he does is seduce you with an extraordinary tale...very exciting. But, actually, he wants to talk about the corruption of autocracy. It's about one-man rule going bad."

Tacitus wrote: “In the year of the consulship of Caius Vipstanus and Caius Fonteius, Nero deferred no more a long meditated crime. Length of power had matured his daring, and his passion for Poppaea daily grew more ardent. As the woman had no hope of marriage for herself or of Octavia's divorce while Agrippina lived, she would reproach the emperor with incessant vituperation and sometimes call him in jest a mere ward who was under the rule of others, and was so far from having empire that he had not even his liberty. "Why," she asked, "was her marriage put off? Was it, forsooth, her beauty and her ancestors, with their triumphal honours, that failed to please, or her being a mother, and her sincere heart? No; the fear was that as a wife at least she would divulge the wrongs of the Senate, and the wrath of the people at the arrogance and rapacity of his mother. If the only daughter-in-law Agrippina could bear was one who wished evil to her son, let her be restored to her union with Otho. She would go anywhere in the world, where she might hear of the insults heaped on the emperor, rather than witness them, and be also involved in his perils." [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“These and the like complaints, rendered impressive by tears and by the cunning of an adulteress, no one checked, as all longed to see the mother's power broken, while not a person believed that the son's hatred would steel his heart to her murder. Nero accordingly avoided secret interviews with her, and when she withdrew to her gardens or to her estates at Tusculum and Antium, he praised her for courting repose. At last, convinced that she would be too formidable, wherever she might dwell, he resolved to destroy her, merely deliberating whether it was to be accomplished by poison, or by the sword, or by any other violent means. Poison at first seemed best, but, were it to be administered at the imperial table, the result could not be referred to chance after the recent circumstances of the death of Britannicus. Again, to tamper with the servants of a woman who, from her familiarity with crime, was on her guard against treachery, appeared to be extremely difficult, and then, too, she had fortified her constitution by the use of antidotes. How again the dagger and its work were to be kept secret, no one could suggest, and it was feared too that whoever might be chosen to execute such a crime would spurn the order.”

Plan to Kill Agrippina

Nero ordering Agrippina's death

Tacitus wrote: “An ingenious suggestion was offered by Anicetus, a freedman, commander of the fleet at Misenum, who had been tutor to Nero in boyhood and had a hatred of Agrippina which she reciprocated. He explained that a vessel could be constructed, from which a part might by a contrivance be detached, when out at sea, so as to plunge her unawares into the water. "Nothing," he said, "allowed of accidents so much as the sea, and should she be overtaken by shipwreck, who would be so unfair as to impute to crime an offence committed by the winds and waves? The emperor would add the honour of a temple and of shrines to the deceased lady, with every other display of filial affection." [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“Nero liked the device, favoured as it also was by the particular time, for he was celebrating Minerva's five days' festival at Baiae. Thither he enticed his mother by repeated assurances that children ought to bear with the irritability of parents and to soothe their tempers, wishing thus to spread a rumour of reconciliation and to secure Agrippina's acceptance through the feminine credulity, which easily believes what joy. As she approached, he went to the shore to meet her (she was coming from Antium), welcomed her with outstretched hand and embrace, and conducted her to Bauli. This was the name of a country house, washed by a bay of the sea, between the promontory of Misenum and the lake of Baiae.

“Here was a vessel distinguished from others by its equipment, seemingly meant, among other things, to do honour to his mother; for she had been accustomed to sail in a trireme, with a crew of marines. And now she was invited to a banquet, that night might serve to conceal the crime. It was well known that somebody had been found to betray it, that Agrippina had heard of the plot, and in doubt whether she was to believe it, was conveyed to Baiae in her litter. There some soothing words allayed her fear; she was graciously received, and seated at table above the emperor. Nero prolonged the banquet with various conversation, passing from a youth's playful familiarity to an air of constraint, which seemed to indicate serious thought, and then, after protracted festivity, escorted her on her departure, clinging with kisses to her eyes and bosom, either to crown his hypocrisy or because the last sight of a mother on the even of destruction caused a lingering even in that brutal heart.”

Bungled Murder of Agrippina

Tacitus wrote: “A night of brilliant starlight with the calm of a tranquil sea was granted by heaven, seemingly, to convict the crime. The vessel had not gone far, Agrippina having with her two of her intimate attendants, one of whom, Crepereius Gallus, stood near the helm, while Acerronia, reclining at Agrippina's feet as she reposed herself, spoke joyfully of her son's repentance and of the recovery of the mother's influence, when at a given signal the ceiling of the place, which was loaded with a quantity of lead, fell in, and Crepereius was crushed and instantly killed. Agrippina and Acerronia were protected by the projecting sides of the couch, which happened to be too strong to yield under the weight. But this was not followed by the breaking up of the vessel; for all were bewildered, and those too, who were in the plot, were hindered by the unconscious majority. The crew then thought it best to throw the vessel on one side and so sink it, but they could not themselves promptly unite to face the emergency, and others, by counteracting the attempt, gave an opportunity of a gentler fall into the sea. Acerronia, however, thoughtlessly exclaiming that she was Agrippina, and imploring help for the emperor's mother, was despatched with poles and oars, and such naval implements as chance offered. Agrippina was silent and was thus the less recognized; still, she received a wound in her shoulder. She swam, then met with some small boats which conveyed her to the Lucrine lake, and so entered her house. [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

Agrippina's death by Antonio Zanchi

“There she reflected how for this very purpose she had been invited by a lying letter and treated with conspicuous honour, how also it was near the shore, not from being driven by winds or dashed on rocks, that the vessel had in its upper part collapsed, like a mechanism anything but nautical. She pondered too the death of Acerronia; she looked at her own wound, and saw that her only safeguard against treachery was to ignore it. Then she sent her freedman Agerinus to tell her son how by heaven's favour and his good fortune she had escaped a terrible disaster; that she begged him, alarmed, as he might be, by his mother's peril, to put off the duty of a visit, as for the present she needed repose. Meanwhile, pretending that she felt secure, she applied remedies to her wound, and fomentations to her person. She then ordered search to be made for the will of Acerronia, and her property to be sealed, in this alone throwing off disguise.

“Nero, meantime, as he waited for tidings of the consummation of the deed, received information that she had escaped with the injury of a slight wound, after having so far encountered the peril that there could be no question as to its author. Then, paralysed with terror and protesting that she would show herself the next moment eager for vengeance, either arming the slaves or stirring up the soldiery, or hastening to the Senate and the people, to charge him with the wreck, with her wound, and with the destruction of her friends, he asked what resource he had against all this, unless something could be at once devised by Burrus and Seneca. He had instantly summoned both of them, and possibly they were already in the secret. There was a long silence on their part; they feared they might remonstrate in vain, or believed the crisis to be such that Nero must perish, unless Agrippina were at once crushed. Thereupon Seneca was so far the more prompt as to glance back on Burrus, as if to ask him whether the bloody deed must be required of the soldiers. Burrus replied "that the praetorians were attached to the whole family of the Caesars, and remembering Germanicus would not dare a savage deed on his offspring. It was for Anicetus to accomplish his promise."

“Anicetus, without a pause, claimed for himself the consummation of the crime. At those words, Nero declared that that day gave him empire, and that a freedman was the author of this mighty boon. "Go," he said, "with all speed and take with you the men readiest to execute your orders." He himself, when he had heard of the arrival of Agrippina's messenger, Agerinus, contrived a theatrical mode of accusation, and, while the man was repeating his message, threw down a sword at his feet, then ordered him to be put in irons, as a detected criminal, so that he might invent a story how his mother had plotted the emperor's destruction and in the shame of discovered guilt had by her own choice sought death.

“Meantime, Agrippina's peril being universally known and taken to be an accidental occurrence, everybody, the moment he heard of it, hurried down to the beach. Some climbed projecting piers; some the nearest vessels; others, as far as their stature allowed, went into the sea; some, again, stood with outstretched arms, while the whole shore rung with wailings, with prayers and cries, as different questions were asked and uncertain answers given. A vast multitude streamed to the spot with torches, and as soon as all knew that she was safe, they at once prepared to wish her joy, till the sight of an armed and threatening force scared them away. Anicetus then surrounded the house with a guard, and having burst open the gates, dragged off the slaves who met him, till he came to the door of her chamber, where a few still stood, after the rest had fled in terror at the attack. A small lamp was in the room, and one slave-girl with Agrippina, who grew more and more anxious, as no messenger came from her son, not even Agerinus, while the appearance of the shore was changed, a solitude one moment, then sudden bustle and tokens of the worst catastrophe. As the girl rose to depart, she exclaimed, "Do you too forsake me?" and looking round saw Anicetus, who had with him the captain of the trireme, Herculeius, and Obaritus, a centurion of marines. "If," said she, "you have come to see me, take back word that I have recovered, but if you are here to do a crime, I believe nothing about my son; he has not ordered his mother's murder."

“The assassins closed in round her couch, and the captain of the trireme first struck her head violently with a club. Then, as the centurion bared his sword for the fatal deed, presenting her person, she exclaimed, "Smite my womb," and with many wounds she was slain.”

Nero’s Reaction to His Mother’s Death

Tacitus wrote: “So far our accounts agree. That Nero gazed on his mother after her death and praised her beauty, some have related, while others deny it. Her body was burnt that same night on a dining couch, with a mean funeral; nor, as long as Nero was in power, was the earth raised into a mound, or even decently closed. Subsequently, she received from the solicitude of her domestics, a humble sepulchre on the road to Misenum, near the country house of Caesar the Dictator, which from a great height commands a view of the bay beneath. As soon as the funeral pile was lighted, one of her freedmen, surnamed Mnester, ran himself through with a sword, either from love of his mistress or from the fear of destruction. [Source: P. Cornelius Tacitus, “The Annals,” Book XIV, A.D. 59-62 A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

“Many years before Agrippina had anticipated this end for herself and had spurned the thought. For when she consulted the astrologers about Nero, they replied that he would be emperor and kill his mother. "Let him kill her," she said, "provided he is emperor."

“But the emperor, when the crime was at last accomplished, realised its portentous guilt. The rest of the night, now silent and stupified, now and still oftener starting up in terror, bereft of reason, he awaited the dawn as if it would bring with it his doom. He was first encouraged to hope by the flattery addressed to him, at the prompting of Burrus, by the centurions and tribunes, who again and again pressed his hand and congratulated him on his having escaped an unforeseen danger and his mother's daring crime. Then his friends went to the temples, and, an example having once been set, the neighbouring towns of Campania testified their joy with sacrifices and deputations. He himself, with an opposite phase of hypocrisy, seemed sad, and almost angry at his own deliverance, and shed tears over his mother's death. But as the aspects of places change not, as do the looks of men, and as he had ever before his eyes the dreadful sight of that sea with its shores (some too believed that the notes of a funereal trumpet were heard from the surrounding heights, and wailings from the mother's grave), he retired to Neapolis and sent a letter to the Senate, the drift of which was that Agerinus, one of Agrippina's confidential freedmen, had been detected with the dagger of an assassin, and that in the consciousness of having planned the crime she had paid its penalty.”

Nero’s Cruelty Outside His Family

Nero reportedly had the senator Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus killed because his expressions were overly melancholy. Suetonius wrote: “Those outside his family he assailed with no less cruelty. It chanced that a comet [Tacitus mentions two comets, one in 60 and the other in 64; see Ann. 14.22, 15.47] had begun to appear on several successive nights, a thing which is commonly believed to portend the death of great rulers. Worried by this, and learning from the astrologer Balbillus that kings usually averted such omens by the death of some distinguished man, thus turning them from themselves upon the heads of the nobles, he resolved on the death of all the eminent men of the State; but the more firmly, and with some semblance of justice, after the discovery of two conspiracies. The earlier and more dangerous of these was that of Piso at Rome; the other was set on foot by Vinicius at Beneventum and detected there. The conspirators made their defense in triple sets of fetters, some voluntarily admitting their guilt, some even making a favor of it, saying that there was no way except by death that they could help a man disgraced by every kind of wickedness. The children of those who were condemned were banished or put to death by poison or starvation; a number are known to have been slain all together at a single meal along with their preceptors and attendants, while others were prevented from earning their daily bread. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Seal of Nero

“After this he showed neither discrimination nor moderation in putting to death whomsoever he pleased on any pretext whatever. To mention but a few instances, Salvidienus Orfitus was charged with having let to certain states as headquarters three shops which formed part of his home near the Forum; Cassius Longinus, a blind jurist, with retaining in the old family tree of his House the mask of Gaius Cassius, the assassin of Julius Caesar; Paetus Thrasea with having a sullen mien, like that of a preceptor. To those who were bidden to die he never granted more than an hour's respite, and to avoid any delay, he brought physicians who were at once to "attend to" such as lingered; for that was the term he used for killing them by opening their veins. It is even believed that it was his wish to throw living men to be torn to pieces and devoured by a monster of Egyptian birth, who would crunch raw flesh and anything else that was given him. Transported and puffed up with such successes, as he considered them, he boasted that no princeps had ever known what power he really had, and he often threw out unmistakable hints that he would not spare even those of the Senate who survived, but would one day blot out the whole order from the State and hand over the rule of the provinces and the command of the armies to the Roman equites and to his freedmen. Certain it is that neither on beginning a journey nor on returning did he kiss any member or even return his greeting; and at the formal opening of the work at the Isthmus the prayer which he uttered in a loud voice before a great throng was that the event might result favorably "for himself and the people of Rome," thus suppressing any mention of the Senate.

“But he showed no greater mercy to the people or the walls of his capital. When someone in a general conversation said: "When I am dead, be earth consumed by fire," he rejoined "Nay, rather while I live," and his action was wholly in accord. For under cover of displeasure at the ugliness of the old buildings and the narrow, crooked streets, he set fire to the city so openly that several ex-consuls did not venture to lay hands on his chamberlains although they caught them on their estates with tow and firebrands, while some granaries near the Golden House, whose room he particularly desired, were demolished by engines of war and then set on fire, because their walls were of stone. For six days and seven nights destruction raged, while the people were driven for shelter to monuments and tombs. At that time, besides an immense number of dwellings, the houses of leaders of old were burned, still adorned with trophies of victory, and the temples of the gods vowed and dedicated by the kings and later in the Punic and Gallic wars, and whatever else interesting and noteworthy had survived from antiquity. Viewing the conflagration from the tower of Maecenas, and exulting, as he said, "with the beauty of the flames," he sang the whole time the "Sack of Ilium," in his regular stage costume. Furthermore, to gain from this calamity too the spoil and booty possible, while promising the removal of the debris and dead bodies free of cost, allowed no one to approach the ruins of his own property; and from the contributions which he not only received, but even demanded, he nearly bankrupted the provinces and exhausted the resources of individuals.”

Seneca and His Suicide at Nero’s Command

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 B.C." 65 AD) served as Nero's tutor and was his friend and confidant of Nero. He dominated Nero's court until he was suspected by Nero of plotting against him and was forced to commit suicide at Nero's command. Seneca wrote about the pursuit of the well-being of the soul and made many observations about Roman history, every day life and politics that have made their way to us today.

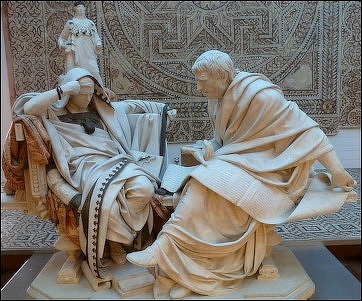

Seneca

On “The Death of Seneca in A.D. 65, Tacitus wrote in Annals 15:64: “Then followed the destruction of Annaeus Seneca, a special joy to the emperor, not because he had convicted him of the conspiracy, but anxious to accomplish with the sword what poison had failed to do. It was, in fact, Natalis alone who divulged Seneca's name, to this extent, that he had been sent to Seneca when ailing, to see him and remonstrate with him for excluding Piso from his presence, when it would have been better to have kept up their friendship by familiar intercourse; that Seneca's reply was that mutual conversations and frequent interviews were to the advantage of neither, but still that his own life depended on Piso's safety. Gavius Silvanus, tribune of a praetorian cohort, was ordered to report this to Seneca and to ask him whether he acknowledged what Natalis said and his own answer. Either by chance or purposely Seneca had returned on that day from Campania, and had stopped at a country house four miles from Rome. Thither the tribune came next evening, surrounded the house with troops of soldiers, and then made known the emperor's message to Seneca as he was at dinner with his wife, Pompeia Paulina, and two friends. [Source: Tacitus: Annals, Book 15, Translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb. Slightly adapted]

“Seneca replied that Natalis had been sent to him and had complained to him in Piso's name because of his refusal to see Piso, upon which he excused himself on the ground of failing health and the desire of rest. "He had no reason," he said, for "preferring the interest of any private citizen to his own safety, and he had no natural aptitude for flattery. No one knew this better than Nero, who had oftener experienced Seneca's free spokenness than his servility." When the tribune reported this answer in the presence of Poppaea and Tigellinus, the emperor's most confidential advisers in his moments of rage, he asked whether Seneca was meditating suicide. Upon this the tribune asserted that he saw no signs of fear, and perceived no sadness in his words or in his looks. He was accordingly ordered to go back and to announce sentence of death. Fabius Rusticus tells us that he did not return the way he came, but went out of his course to Faenius, the commander of the guard, and having explained to him the emperor's orders, and asked whether he was to obey them, was by him admonished to carry them out, for a fatal spell of cowardice was on them all. For this very Silvanus was one of the conspirators, and he was now abetting the crimes which he had united with them to avenge. But he spared himself the anguish of a word or of a look, and merely sent in to Seneca one of his centurions, who was to announce to him his last doom.

“Seneca, quite unmoved, asked for tablets on which to inscribe his will, and, on the centurion's refusal, turned to his friends, protesting that as he was forbidden to requite them, he bequeathed to them the only, but still the noblest possession yet remaining to him, the pattern of his life, which, if they remembered, they would win a name for moral worth and steadfast friendship. At the same time he called them back from their tears to manly resolution, now with friendly talk, and now with the sterner language of rebuke. "Where," he asked again and again, "are your maxims of philosophy, or the preparation of so many years' study against evils to come? Who knew not Nero's cruelty? After a mother's and a brother's murder, nothing remains but to add the destruction of a guardian and a tutor."

“Having spoken these and like words, meant, so to say, for all, he embraced his wife; then softening awhile from the stern resolution of the hour, he begged and implored her to spare herself the burden of perpetual sorrow, and, in the contemplation of a life virtuously spent, to endure a husband's loss with honourable consolations. She declared, in answer, that she too had decided to die, and claimed for herself the blow of the executioner. There upon Seneca, not to thwart her noble ambition, from an affection too which would not leave behind him for insult one whom he dearly loved, replied: "I have shown you ways of smoothing life; you prefer the glory of dying. I will not grudge you such a noble example. Let the fortitude of so courageous an end be alike in both of us, but let there be more in your decease to win fame."

Nero and Seneca

“Then by one and the same stroke they sundered with a dagger the arteries of their arms. Seneca, as his aged frame, attenuated by frugal diet, allowed the blood to escape but slowly, severed also the veins of his legs and knees. Worn out by cruel anguish, afraid too that his sufferings might break his wife's spirit, and that, as he looked on her tortures, he might himself sink into irresolution, he persuaded her to retire into another chamber. Even at the last moment his eloquence failed him not; he summoned his secretaries, and dictated much to them which, as it has been published for all readers in his own words, I forbear to paraphrase.

“Nero meanwhile, having no personal hatred against Paulina and not wishing to heighten the odium of his cruelty, forbade her death. At the soldiers' prompting, her slaves and freedmen bound up her arms, and stanched the bleeding, whether with her knowledge is doubtful. For as the vulgar are ever ready to think the worst, there were persons who believed that, as long as she dreaded Nero's relentlessness, she sought the glory of sharing her husband's death, but that after a time, when a more soothing prospect presented itself, she yielded to the charms of life. To this she added a few subsequent years, with a most praise worthy remembrance of her husband, and with a countenance and frame white to a degree of pallor which denoted a loss of much vital energy.

“Seneca meantime, as the tedious process of death still lingered on, begged Statius Annaeus, whom he had long esteemed for his faithful friendship and medical skill, to produce a poison with which he had some time before provided himself, same drug which extinguished the life of those who were condemned by a public sentence of the people of Athens. It was brought to him and he drank it in vain, chilled as he was throughout his limbs, and his frame closed against the efficacy of the poison. At last he entered a pool of heated water, from which he sprinkled the nearest of his slaves, adding the exclamation, "I offer this liquid as a libation to Jupiter the Deliverer." He was then carried into a bath, with the steam of which he was suffocated, and he was burnt without any of the usual funeral rites. So he had directed in a codicil of his will, when even in the height of his wealth and power he was thinking of his life's close.”

Nero and the Persecution of Christians

Nero allegedly ordered the slaughter of Christians. Among them, according to tradition, were the apostles Peter and Paul. Christians, wrote Tacitus, "were nailed on crosses...sewn up in the skins of wild beasts, and exposed to the fury of dogs; others again, smeared over with combustible materials, were used as torches to illuminate the night."

Peter, Paul, Simon Magus and Nero by Filippino Lippi

Nero began persecuting Christians on the grounds of disloyalty and blamed them, along with Jews, for the great fire in Rome in A.D. 64, something which he is believed to have been was involved in. Tacitus wrote that before the killing of Christians, Nero used them to amuse the masses. Some were dressed in furs, to be killed by dogs. Others were crucified. Still others were set on fire. Although some persecution of Christian is believed to have occurred, and some it was very cruel, the extent of it has been wildly exaggerated. Most of the victims were bishops or other male leaders. Nero is believed to have accused the Christians of starting the Rome fire in order to shield himself from the suspicion of setting the fire himself.

The height of the persecution of Christians was not during the reign of Nero, but much later. Domitian, Marcus Aurelius and Valerian all brutalized Christians after A.D. 150, when Christians held many high positions and presented a threat as "state within a state." In A.D. 202 the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus made baptism a criminal act. In A.D. 250 Emperor Decius increased the persecution of Christians.

According to the traditional story, in A.D. 67, in the last year of Nero’s reign, St. Peter was hung upside down and beheaded at the Circus Maximus during a wave of brutal anti-Christian persecution after the burning of Rome. His brutal treatment was partly of the result of his request not to be crucified, because he didn't consider himself worthy of the treatment of Jesus. After Peter died, it is said, his body was taken to a burial ground, situated where St. Peter's cathedral now stands. His body was entombed and later secretly worshiped.

It is not exactly clear what happened to St. Paul but it is believed that he was martyred in A.D. 64, the year that Nero blamed the great fire of Rome on the Christian and Jews. Before he was killed St. Paul invoked his right as a Roman citizen to be beheaded. His wish was granted. According to some, Paul was martyred at the site occupied by the Monastery of the Three Fountains in Rome. The Cathedral of St. John Lateran, the oldest Christian basilica in Rome, founded by Constantine on A.D. 314, contains reliquaries said to hold the heads of St. Paul and St. Peter and the chopped off finger doubting Thomas stuck in Jesus' wound.

Tacitus’s Account of Nero’s Persecution of the Christians

Our understanding of the “first persecution” of Christians under Nero largely comes from the account of the Roman historian Tacitus, which is of great interest because it contains the first reference by a pagan author to Christ and his followers. The following passage shows not only the cruelty of Nero and the terrible sufferings of the early Christian martyrs, but also the pagan prejudice against the new religion. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Tacitus wrote: says: “In order to drown the rumor, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. [Source: “Annals,” Book. XV., Ch. 44, by P. Cornelius Tacitus, A.D. 109, translated by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb]

Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired. Nero offered his own gardens for this spectacle. The people were moved with pity for the sufferers; for it was felt that they were suffering to gratify Nero’s cruelty, not from considerations for the public welfare.”

Did Nero Really Persecute the Christians as Alleged

Peter by Caravaggio

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine: It must be conceded upfront: Nero did kill Christians. Simmering public resentment over the Great Fire put enormous pressure on the government to find a scapegoat. Early accounts make it unclear whether Christians were persecuted for their religious beliefs or simply as an outsider group — Drinkwater says the latter — but they were easily framed for arson. Whatever he was up to, Nero wasn’t trying to stamp out the nascent faith, which, at this point, was taking shape more in the Middle East than in Rome. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

“The Christians whom Nero did kill were never thrown to the lions before a crowd of baying spectators in the Colosseum, as the story goes. For one thing, the Colosseum wasn’t even built yet. More to the point, from what we know, Nero had little taste for the kind of blood sport we associate with popular Roman entertainment. As a philhellene, he would much rather watch a good chariot race than see two armed men slice each other up. When protocol demanded that he show up at gladiatorial games, Nero is said to have remained in his box with the curtains drawn. He took some heat for this. It was considered insufficiently Roman of him.

“The Christians Nero executed for setting the Great Fire were mostly burned in his own gardens, which conforms to the standard Roman legal practice of fitting the punishment to the crime. And that appears to have been the end of it, at least at the time. The public was appeased and the Christians of Rome stayed silent. “Persecution isn’t mentioned at all in the early Christian sources,” says Drinkwater. “That idea comes up only much later, in the third century, and is fully accepted only in the fourth century.”

“When the idea finally surfaces in Christian polemics, it appears with a vengeance. The Book of Revelation was interpreted to cast Nero as the Anti-Christ: The numerical equivalents of the Hebrew letters that spell “Neron Caesar” come out to 666 — the “number of the beast.” Do with that what you will. Lactantius, a tutor of the Christian Emperor Constantine’s son, wrote On the Deaths of the Persecutors in the early fourth century. He has this to say: “Nero, being the abominable and criminal tyrant that he was, rushed into trying to overturn the heavenly temple and abolish righteousness, and, the first persecutor of the servants of God, he nailed Peter to the cross and killed Paul. For this he did not go unpunished.”

“Never mind that Nero has an alibi for Peter’s death: There’s no evidence Peter was ever in Rome. Paul was there, from A.D. 60 to 62, and he may even have been killed there, but that was well before the so-called “Neronian persecution.” But none of that matters much anymore. Early Christians and the Flavians set their stamp on the written record early, and they held a grudge.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024