Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory / Science and Nature

ANCIENT GREEK UNDERSTANDING OF GEOGRAPHY

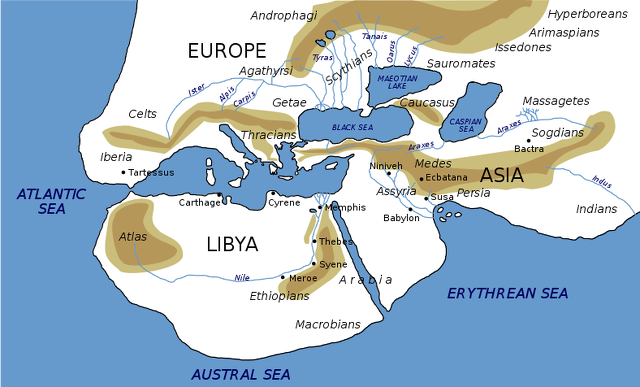

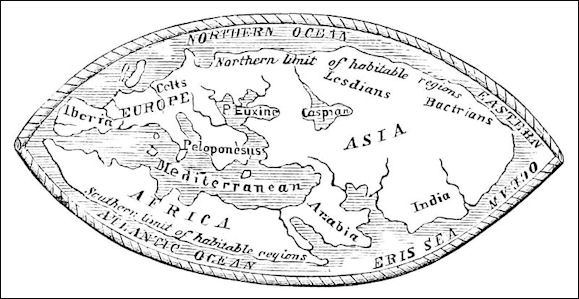

Claudius Ptolemaeus No maps drawn up by the ancient Greeks have survived. According to a description by Herodotus, the known world in Greek times was drawn as a neat parallelogram with the Danube and the Nile as the boundaries. The "equator" was a diagonal line running through the middle of the map. Asia Minor was described as having an ideal climate because it was intersected by the equator and it was "midway between the extreme points of the summer and winter rising and settings of the sun." [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

In the octagonal Tower of the Winds in Athens (second century B.C.) the four cardinal direction are depicted by winds as are the four in-between directions (northeast, southwest, etc.). Certain myths and symbols are attached with each one. The puffy cheeked faces of blowing winds that we see on many old maps dates back to the Greeks. All the Greek winds had names and after time these names became synonymous with the direction from which the came. This set the precedent as to why we determine direction from where it comes from rather than where it goes.∞

Aristotle suggested in the 3rd century B.C. that the world was a sphere based on the shadow cast on the moon during an eclipse. Miletus and Thales proposed in 585 B.C. that the Earth was a disk that floated on water. Anaximader envisioned it as cylinder crowned by a disk of inhabited land while Anazimenes suggested it was a rectangle floating on compressed air. The Pythagoreans and Plato believed the world was a sphere based on their belief that the sphere was the most perfect shape. Aristarchus (310-230 B.C.) measured the Earth’s tilt on its axis and proposed the Earth’s orbits the sun.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SCIENCE IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MATHEMATICS IN ANCIENT GREECE: GEOMETRY, MEASUREMENTS, THEOREMS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ASTRONOMY IN IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TIME IN ANCIENT GREECE: CLOCKS, DIVISIONS, DAYS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ATOMISTS: LEUCIPPUS AND DEMOCRITUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TECHNOLOGY factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Geography: The Discovery of the World in Classical Greece and Rome” (2017)

by Duane W. Roller Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece” by Robert Morkot (1997) Amazon.com;

“Strabo's Geography: A Translation for the Modern World Hardcover”

by Strabo, translated by Sarah Pothecary Amazon.com;

“Delphi Complete Works of Strabo - Geography (Illustrated)” Kindle Amazon.com;

“A Historical and Topographical Guide to the Geography of Strabo”

by Duane W. Roller (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Mediterranean” by Michael Grant (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and Greek Civilization” by Jacob Burckhardt (1902) Amazon.com;

“Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization” by Simon Hornblowwer and Anthony Spawforth Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric Times to Hellenistic Times” by Thomas R. Martin (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way” by Edith Hamilton (1930) Amazon.com;

“Sailing Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter “ by Thomas Cahill, Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Histories” by Herodotus (Landmark) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“Time Museum Catalogue of the Collection: Time Measuring Instruments, Part 1 : Astrolabes, Astrolabe Related Instruments” (1986) by A. J. Turner Amazon.com;

“Introducing the Ancient Greeks: From Bronze Age Seafarers to Navigators of the Western Mind” by Edith Hall Amazon.com;

“Greek Science of the Hellenistic Era: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Georgia L. Irby-Massie (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

Explorers and Ancient Greece

A Carthaginian navigator named Hanno explored the west coast of Africa between 500 and 450 B.C. It is not known how far he got. The Greek geographer Pythea visited Britain around 300 B.C.

Alexander the Great spread knowledge of the Western world as far east as India. The Crete mariner named Nearchus, who had joined Alexander the Great, sailed from the Indus River back to the Middle East in 325-324 B.C.

A Greek named Eudoxus made on of the first voyages between Egypt and India. Around 120 B.C., he sailed across the Arabian Sea and down the east coast of Africa. By A.D. 100, Greek and Roman mariners were sailing east of India.

Herodotus and the World

In the 5th Century B.C. Herodotus wrote extensively about Babylon, Arabia, Egypt and Central Asia. See Neo-Babylonians Under MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com and See Ancient Egyptian History Under ANCIENT EGYPTIANS, especially the Nile Under Themes, Early History, Archaeology, the Pyramids Under the Old Kingdom and Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans africame.factsanddetails.com ; Descriptions by Herodotus are scattered here and there in many of the articles.

Gareth Dorrian and Ian Whittaker wrote: The Histories by Herodotus (484BC to 425BC) offers a remarkable window into the world as it was known to the ancient Greeks in the mid fifth century B.C.. Almost as interesting as what they knew, however, is what they did not know. This sets the baseline for the remarkable advances in their understanding over the next few centuries — simply relying on what they could observe with their own eyes. [Source: Gareth Dorrian, Post Doctoral Research Fellow in Space Science, University of Birmingham and Ian Whittaker, Lecturer in Physics, Nottingham Trent University, The Conversation, April 24, 2020]

“Herodotus claimed that Africa was surrounded almost entirely by sea. How did he know this? He recounts the story of Phoenician sailors who were dispatched by King Neco II of Egypt (about 600BC), to sail around continental Africa, in a clockwise fashion, starting in the Red Sea. This story, if true, recounts the earliest known circumnavigation of Africa, but also contains an interesting insight into the astronomical knowledge of the ancient world.

“The voyage took several years. Having rounded the southern tip of Africa, and following a westerly course, the sailors observed the Sun as being on their right hand side, above the northern horizon. This observation simply did not make sense at the time because they didn’t yet know that the Earth has a spherical shape, and that there is a southern hemisphere.

Eratosthenes, Longitude, Latitude and Measuring the World

Eratosthenes Eratosthenes was a Ptolemaic Greek scientist, librarian, theater critic and a famous scholar at the Alexandrian library. He was the first man to divide the Earth into northern and southern hemispheres. He also devised a system of north-south and east-west lines. Hipparcus extended these lines around the whole world, and said that by simply knowing the coordinates, any place on earth could be located.

Eratosthenes also came up with the word "degree" and the idea of dividing the Earth into 360 meridians that were a 70 miles apart at the equator (calculations which are more or less true today). Ptolemy, the author of “Geography” , applied the grid system to cartography and divided Hipparcus's degrees into "minutes" and "seconds." The early Greek system of longitude and latitude worked better on a flat world than a spherical one. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Eratosthenes made the first calculation of the circumference of the Earth. During the summer solstice, he had heard, sunlight penetrated to bottom of well in the town of the Syene (modern Aswan). This meant the sun was directly overhead there on that date. He didn't know this at the time but this also meant that Syene was located on the imaginary line we now call the Tropic of Cancer.

On the the summer solstice on June 21st, 240 B.C., without leaving the Alexandria library grounds where he worked, Eratosthenes measured the shadow cast by a column at noon and worked out the angle of its shadow was 7½ degrees. He knew that Syene was about 500 miles away from Alexandria and that 7½̊ was about one fiftieth of a circle. More or less by multiplying the distance between the two cities (500 miles) by 50 (the 50 segments in a circle) he calculated the Earth had a circumference of 25,200 miles, only 340 miles longer than the true figure of 24,860 miles. Eratosthenes also calculated the distance of the Earth to the sun was 92 million miles, also an astonishingly close number.

Ptolemy, Geography and the Earth at the Center of the Universe

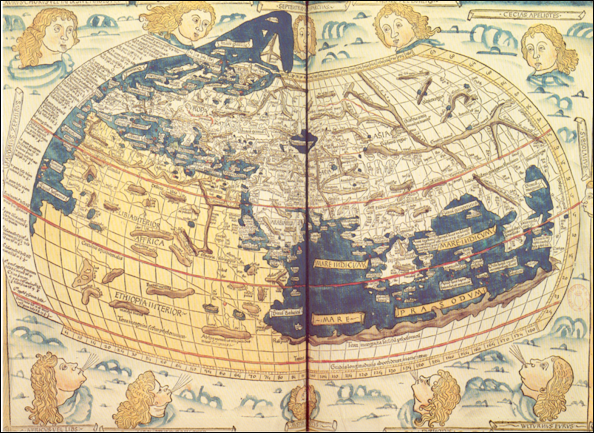

Claudius Ptolemaeus, Ptolemy for short, was a Greco-Roman astronomer who combined centuries of Greek learning with 14 years of observations of the stars and planets to produce “ Geography” (A.D. 141), which declared that the Earth was at the center of the universe and used this theory to explain and predict the positions of stars and planets. Ptolemy is regarded as the father of modern geography. He also wrote about music, optics, kings, chronology and astrology, but he is remembered most for his assertion the Earth was the center of the universe.

Ptolemy wrote "Geography looks at the position rather than quality, noting the relation of distances everywhere, and emulating the art of painting only in some of its major description.” Ptolemy's system of latitude and longitude used lines that were a uniform distance apart and were represented with curved lines to compensate for the spherical shape of the Earth. The first longitude were not equally spaced apart like those today; they ran through well known places like Alexandria, Rhodes, the Pillars of Hercules and the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Ptolemy improved this system. However he grossly underestimated the circumference of the Earth. He declared it to be 18,000 miles (as opposed to the true figure of about 24,586 miles)

Ptolemy may have also been the one who invented the words "longitude" and "latitude." The principals he laid out in “ Geography” were the basis for the knowledge of geography, maps and atlases in Europe until the 17th century. Barthalamule Dias and Vasco de Gama had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope of southern Africa maps based on Ptolemy's view of the world showed the Indian Ocean to be as land bound as the Mediterranean Sea. His erroneous calculation of the circumference of the Earth was one reason why Columbus decided to sail of to India across the Atlantic (based on Ptolemy's calculations Columbus thought that Asia was closer than it is really was).∞

World of Ptolemy as shown by Johannes de Armsshein of Ulm (1482)

Ptolemy's system endured for more than 1,400 years (until Copernicus), partly because the Roman Catholic Church liked "the human-centered view of the world." Ptolemy was ignored during the Middle Ages and many says his revival in the Renaissance is once of the forces that spurred thinking about man’s place in the world and the universe. Even though the Greeks had figured out the Earth was round, the Christians put forth the idea that seas were probably unnavigable, and if they were navigable, one should not venture too close to paradise which was not to far away. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

Strabo: the Geography

Strabo (64 B.C. – c. A.D. 24) was a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who came from Asia Minor at around the time the Roman Republic was becoming the Roman Empire. Strabo is best known for his work "Geographica" ("Geography"), which describes the history and characteristics of people and places in different regions known during his lifetime. Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus (in present-day Turkey). He traveled extensively during his life, venturing to Egypt and Kush (Sudan) and as going far south as Ethiopia. He lived in Rome and journey throughout throughout the Mediterranean and Near East. Strabo studied under several prominent teachers of various specialities throughout his early life at different stops during his Mediterranean travels. "Geographica" was not utilized much by contemporary writers but numerous copies survived throughout the Byzantine Empire. It first appeared in Western Europe in Rome as a Latin translation in 1469.

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “Now I shall tell what part of the land and sea I have myself visited and concerning what part I have trusted to accounts given by others by word of mouth or in writing. I have travelled westward from Armenia as far as the regions of Tyrrhenia opposite Sardinia, and southward from the Euxine Sea as far as the frontiers of Ethiopia. And you could not find another person among the writers on geography who has travelled over much more of the distances just mentioned than I; indeed, those who have travelled more than I in the western regions have not covered as much ground in the east, and those who have travelled more in the eastern countries are behind me in the western; and the same holds true in regard to the regions towards the south and north. However, the greater part of our material both they and I receive by hearsay and then form our ideas. . . . And he who claims that only those have knowledge who have actually seen abolishes the criterion of the sense of hearing, though this sense is much more important than sight for the purposes of science. [Source: Strabo, “Geography of Strabo,” 8 volumes, translated by Horace L. Jones, (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1917), vol. 1, pp. 451-2]

“In particular the writers of the present time can give a better account of the Britons, the Germans, the peoples both north and south of the Ister, the Getans, the Tyregetans, the Bastarnians, and, furthermore, the peoples in the regions of the Caucasus, such as the Albanians and the Iberians. Information has been given us also concerning Hyrcania and Bactriana by the writers of Parthian histories, in which they marked off those countries more definitely than many other writers. . . .

Earth of the later Greeks

Ancient Greek Writers on India and Asia

A Greek named Eudoxus made on of the first voyages between Egypt and India. Around 120 B.C., he sailed across the Arabian Sea and down the east coast of Africa. By A.D. 100, Greek and Roman mariners were sailing east of India.

Herodotus wrote in “The History of the Persian Wars,” (c.430 B.C.): “III.106: It seems as if the extreme regions of the earth were blessed by nature with the most excellent productions, just in the same way that Hellas enjoys a climate more excellently tempered than any other country. In India, which, as I observed lately, is the furthest region of the inhabited world towards the east, all the four-footed beasts and the birds are very much bigger than those found elsewhere, except only the horses, which are surpassed by the Median breed called the Nisaean. Gold too is produced there in vast abundance, some dug from the earth, some washed down by the rivers, some carried off in the mode which I have but now described. And further, there are trees which grow wild there, the fruit whereof is a wool exceeding in beauty and goodness that of sheep. The natives make their clothes of this tree-wool.”

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” Book XV: On India (c. A.D. 20): “1...I must now begin with India, for it is the first and largest country that lies out towards the east. 2. But it is necessary for us to hear accounts of this country with indulgence, for not only is it farthest away from us, but not many of our people have seen it; and even those who have seen it, have seen only parts of it, and the greater part of what they say is from hearsay; and even what they saw they learned on a hasty passage with an army through the country. Wherefore they do not give out the same accounts of the same things, even though they have written these accounts as though their statements had been carefully confirmed. And some of them were both on the same expedition together and made their sojourns together, like those who helped Alexander to subdue Asia; yet they all frequently contradict one another. But if the differ thus about what was seen, what must we think of what they report from hearsay?[Source: Strabo, “Geography of Strabo,” 8 volumes, translated by Horace L. Jones, (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1917), vol. 1, pp. 451-2]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK WRITERS AND HISTORIANS ON INDIA AND ASIA factsanddetails.com ANCIENT GREEK AND ROMAN WRITERS ON TRAVELING BY SEA TO INDIA factsanddetails.com

Ancient Sources on the Middle East and North Africa

On Arabia, Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C.: “The Arabs keep such pledges more religiously than almost any other people. They plight faith with the forms following. When two men would swear a friendship, they stand on each side of a third: he with a sharp stone makes a cut on the inside of the hand of each near the middle finger, and, taking a piece from their dress, dips it in the blood of each, and moistens therewith seven stones lying in the midst, calling the while on Bacchus and Urania. After this, the man who makes the pledge commends the stranger (or the citizen, if citizen he be) to all his friends, and they deem themselves bound to stand to the engagement. They have but these two gods, to wit, Bacchus and Urania; and they say that in their mode of cutting the hair, they follow Bacchus. Now their practice is to cut it in a ring, away from the temples. Bacchus they call in their language Orotal, and Urania, Alilat. . . .There is a great river in Arabia, called the Corys, which empties itself into the Erythraean sea. The Arabian king, they say, made a pipe of the skins of oxen and other beasts, reaching from this river all the way to the desert, and so brought the water to certain cisterns which he had dug in the desert to receive it. It is a twelve days' journey from the river to this desert tract. And the water, they say, was brought through three different pipes to three separate places. . . .The Arabs brought every year a thousand talents of frankincense. [Source: Herodotus: The Histories, Book III, c. 430 B.C. Herodotus, The Histories of Herodotus (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1898) sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/arabia ]

On ancient Mauretania, Strabo wrote in “Geography,” XVII.iii.1-11 (A.D. c. 22): “The writers who have divided the habitable world according to continents divide it unequally. Africa wants so much of being a third part of the habitable world that, even if it were united to Europe, it would not be equal to Asia; perhaps it is even less than Europe; in resources it is very much inferior, for a great part of the inland and maritime country is desert. It is spotted over with small habitable parts, which are scattered about, and mostly belonging to nomad tribes. Besides the desert state of the country, its being a nursery of wild beasts is a hindrance to settlement in parts which could be inhabited. It comprises also a large part of the torrid zone. All the sea coast in our quarter, situated between the Nile and the Pillars (of Hercules), particularly that which belonged to the Carthaginians, is fertile and inhabited. And even in this tract, some spots destitute of water intervene, as those about the Syrtes, the Marmaridae, and the Catabathmus. [Source: Strabo, “The Geography of Strabo” translated by H. C. Hamilton, esq., & W. Falconer (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857), pp. 279-284]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT SOURCES ON ARABS AND THE MIDDLE EAST africame.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT SOURCES ON MAURITANIA, LIBYA AND WESTERN NORTH AFRICA africame.factsanddetails.com

Africans and Ancient Greeks

Tales of Ethiopia as a mythical land at the farthest edges of the earth are recorded in some of the earliest Greek literature of the eighth century B.C., including the epic poems of Homer. Greek gods and heroes, like Menelaos, were believed to have visited this place on the fringes of the known world. However, long before Homer, the seafaring civilization of Bronze Age Crete, known today as Minoan, established trade connections with Egypt. The Minoans may have first come into contact with Africans at Thebes, during the periodic bearing of tribute to the pharaoh. In fact, paintings in the tomb of Rekhmire, dated to the fourteenth century B.C., depict African and Aegean peoples, most likely Nubians and Minoans. However, with the collapse of the Minoan and Mycenaean palaces at the end of the Late Bronze Age, trade connections with Egypt and the Near East were severed as Greece entered a period of impoverishment and limited contact. [Source: Sean Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

image of an African from 900 BC

“During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., the Greeks renewed contacts with the northern periphery of Africa. They established settlements and trading posts along the Nile River and at Cyrene on the northern coast of Africa. Already at Naukratis, the earliest and most important of the trading posts in Africa, Greeks were certainly in contact with Africans. It is likely that images of Africans, if not Africans themselves, began to reappear in the Aegean. In the seventh and early sixth centuries B.C., Greek mercenaries from Ionia and Caria served under the Egyptian pharaohs Psametikus I and II. \^/

“All black Africans were known as Ethiopians to the ancient Greeks, as the fifth-century B.C. historian Herodotus tells us, and their iconography was narrowly defined by Greek artists in the Archaic (ca. 700–480 B.C.) and Classical (ca. 480–323 B.C.) periods, black skin color being the primary identifying physical characteristic. It is recorded that Ethiopians were among King Xerxes' troops when Persia invaded Greece in 480 B.C. Thus, the Greeks would have come into contact with large numbers of Africans at this time. Nonetheless, most ancient Greeks had only a vague understanding of African geography. They believed that the land of the Ethiopians was located south of Egypt. In Greek mythology, the pygmies were the African race that lived furthest south on the fringes of the known world, where they engaged in mythic battles with cranes. \^/

“Ethiopians were considered exotic to the ancient Greeks and their features contrasted markedly with the Greeks' own well-established perception of themselves. The black glaze central to Athenian vase painting was ideally suited for representing black skin, a consistent feature used to describe Ethiopians in ancient Greek literature as well. Ethiopians were featured in the tragic plays of Aeschylus, Sophokles, and Euripides; and preserved comic masks, as well as a number of vase paintings from this period, indicate that Ethiopians were also often cast in Greek comedies. \^/

“Well into the fourth century B.C., Ethiopians were regularly featured in Greek vase painting, especially on the highly decorative red-figure vases produced by the Greek colonies in southern Italy. One type shows an Ethiopian being attacked by a crocodile, most likely an allusion to Egypt and the Nile River. Depictions of Ethiopians in scenes of everyday life are rare at this time, although one tomb painting from a Greek cemetery near Paestum in southern Italy shows an Ethiopian and a Greek in a boxing competition. \^/

“With the establishment of the Ptolemaic dynasty and Macedonian rule in Egypt, after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C., came an increased knowledge of Nubia (in modern Sudan), the neighboring kingdom along the lower Nile ruled by kings who resided in the capital cities of Napata and later Meroe. Cosmopolitan metropolises,including Alexandria in the Nile Delta, became centers where significant Greek and African populations lived together. \^/

“During the Hellenistic period (ca. 323–31 B.C.), the repertoire of African imagery in Greek art expanded greatly. While scenes related toEthiopians in mythology became less common, many more types occurred that suggest they constituted a larger minority element in the population of the Hellenistic world than the preceding period. Depictions of Ethiopians as athletes and entertainers are suggestive of some of the occupations they held. Africans also served as slaves in ancient Greece, together with both Greeks and other non-Greek peoples who were enslaved during wartime and through piracy. However, scholars continue to debate whether or not the ancient Greeks viewed black Africans with racial prejudice. \^/

“Large-scale portraits of Ethiopians made by Greek artists appear for the first time in the Hellenistic period and high-quality works, such as images on gold jewelry and fine bronze statuettes, are tangible evidence of the integration of Africans into various levels of Greek society.” \^/

See Separate Article: ANCIENT SOURCES ON NUBIA AND ETHIOPIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Pausanias on Ethiopians

bronze Ethiopian from the 2nd or 3rd century BC

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “As to the Aethiopians, I could hazard no guess myself, nor could I accept the statement of those who are convinced that the Aethiopians have been carved upon the cup be cause of the river Ocean. For the Aethiopians, they say, dwell near it, and Ocean is the father of Nemesis. It is not the river Ocean, but the farthest part of the sea navigated by man, near which dwell the Iberians and the Celts, and Ocean surrounds the island of Britain. But of the Aethiopians beyond Syene, those who live farthest in the direction of the Red Sea are the Ichthyophagi (Fish-eaters), and the gulf round which they live is called after them. The most righteous of them inhabit the city Meroe and what is called the Aethiopian plain. These are they who show the Table of the Sun,1 and they have neither sea nor river except the Nile. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“There are other Aethiopians who are neighbours of the Mauri and extend as far as the Nasamones. For the Nasamones, whom Herodotus calls the Atlantes, and those who profess to know the measurements of the earth name the Lixitae, are the Libyans who live the farthest close to Mount Atlas, and they do not till the ground at all, but live on wild vines. But neither these Aethiopians nor yet the Nasamones have any river. For the water near Atlas, which provides a beginning to three streams, does not make any of the streams a river, as the sand swallows it all up at once. So the Aethiopians dwell near no river Ocean.

“The water from Atlas is muddy, and near the source were crocodiles of not less than two cubits, which when the men approached dashed down into the spring. The thought has occurred to many that it is the reappearance of this water out of the sand which gives the Nile to Egypt. Mount Atlas is so high that its peaks are said to touch heaven, but is inaccessible because of the water and the presence everywhere of trees. Its region indeed near the Nasamones is known, but we know of nobody yet who has sailed along the parts facing the sea. I must now resume.

“Neither this nor any other ancient statue of Nemesis has wings, for not even the holiest wooden images of the Smyrnaeans have them, but later artists, convinced that the goddess manifests herself most as a consequence of love, give wings to Nemesis as they do to Love. I will now go onto describe what is figured on the pedestal of the statue, having made this preface for the sake of clearness. The Greeks say that Nemesis was the mother of Helen, while Leda suckled and nursed her. The father of Helen the Greeks like everybody else hold to be not Tyndareus but Zeus.[1.33.8] Having heard this legend Pheidias has represented Helen as being led to Nemesis by Leda, and he has represented Tyndareus and his children with a man Hippeus by name standing by with a horse. There are Agamemnon and Menelaus and Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles and first husband of Hermione, the daughter of Helen. Orestes was passed over because of his crime against his mother, yet Hermione stayed by his side in everything and bore him a child. Next upon the pedestal is one called Epochus and another youth; the only thing I heard about them was that they were brothers of Oenoe, from whom the parish has its name.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024