Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.) / Government and Justice

HISTORY OF DEMOCRACY IN ANCIENT GREECE

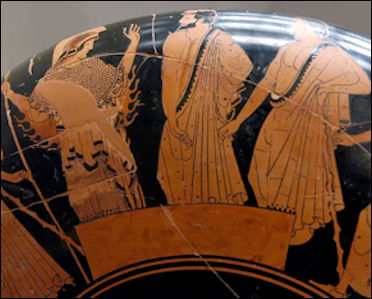

voting scene in ancient Greece The ancient Greeks are credited with founding democracy (a word derived from Greek words for people, demos , and kratos , rule) and literally means “rule by the people." In the early days most city-states, however, were ruled by local tyrants or oligarchies that formed citizen councils. The philosopher Democritus had nothing really to do with democracy. He is known for his theory on atoms.

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote in for BBC: “The ancient Greek word demokratia was ambiguous. It meant literally 'people-power'. But who were the people to whom the power belonged? Was it all the people - the 'masses'? Or only some of the people - the duly qualified citizens? The Greek word demos could mean either. There's a theory that the word demokratia was coined by democracy's enemies, members of the rich and aristocratic elite who did not like being outvoted by the common herd, their social and economic inferiors. If this theory is right, democracy must originally have meant something like 'mob rule' or 'dictatorship of the proletariat'. [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, University of Cambridge, BBC, February 17, 2011 Cartledge is Professor of Greek History at the University of Cambridge. He is the author, co-author, editor and co-editor of 20 or so books, the latest being Alexander the Great: The Hunt for a New Past (Pan Macmillan, London, 2004). He was chief historical consultant for the BBC TV series 'The Greeks'.]

“By the time of Aristotle (fourth century B.C.) there were hundreds of Greek democracies. Greece in those times was not a single political entity but rather a collection of some 1,500 separate poleis or 'cities' scattered round the Mediterranean and Black Sea shores 'like frogs around a pond', as Plato once charmingly put it. Those cities that were not democracies were either oligarchies - where power was in the hands of the few richest citizens - or monarchies, called 'tyrannies' in cases where the sole ruler had usurped power by force rather than inheritance. Of the democracies, the oldest, the most stable, the most long-lived, but also the most radical, was Athens.

RELATED ARTICLES: ANCIENT GREEK CLASSICAL AGE (500 B.C. TO 323 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ; POWERFUL POLISES (CITY STATES) OF ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; ANCIENT ATHENS europe.factsanddetails.com ; GOVERNMENT IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; MAJOR FIGURES IN ANCIENT GREEK DEMOCRACY europe.factsanddetails.com ; SOLON europe.factsanddetails.com ; PERICLES: HIS LIFE, SPEECHES AND IMPACT ON ANCIENT ATHENS AND GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Democracy: A Life” by Paul Cartledge (2016) Amazon.com;

"Democracy's Beginning: The Athenian Story” by Thomas N. Mitchell (2020) Amazon.com;

“Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece” by Kurt A. A. Raaflaub , Paul Cartledge, et al. | Oct 15, 2008 Amazon.com;

The Athenian Constitution (Penguin Classics) by Aristotle Amazon.com;

“Athens and Athenian Democracy” by Robin Osborne (2010) Amazon.com;

“Citizenship in Classical Athens” by Josine Blok (2017) Amazon.com;

“Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People” by Josiah Ober (1989) Amazon.com;

“War, Democracy and Culture in Classical Athens” by David Pritchard (2010) Amazom.com

“Athens, A Portrait of a City in Its Golden Age by Christian Meier” (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holy & Company, 1998) Amazom.com

“Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy” by John R. Hale (2009) Amazon.com;

“ The Rise of Athens: The Story of the World's Greatest Civilization” by Anthony Everitt (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” by Plutarch (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy” by Hugh Bowden (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1998) Amazon.com;

“Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece” by Robin Waterfield (2018) Amazon.com;

Did Athens Really Invent Democracy?

J. Wisniewski wrote in Listverse: If there’s one thing we all remember from Western Civilization 101, it’s that Athens invented democracy. Not many of us remember the exact date (480 B.C.), but we remember the invention all right. And yet 18 ancient Greek city-states possessed a democratic government before Athens. Evidence says some of those states had democracy as much as a full century earlier.It seems that Athens, rather than inventing a more egalitarian form of government, actually reacted to a larger Hellenic trend, implementing an already tried-and-true type of governance. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

The city-state of Ambracia, for example, was ruled by a popular assembly starting in 580 B.C. And these democratic predecessors weren’t obscure cities. City-states like Syracuse and Elis—the city that hosted the ancient Olympics—are among those that beat Athens to the democratic punch. Syracuse and Elis were also the models for many successive democracies in their respective regions (Sicily and the Peloponnese).

Athens gets all the credit mostly because more sources cover it, making it the easiest ancient Greek city-state to study. About one-third of nearly every Greek history book is devoted to Classical Athens thanks to the surviving literary riches from that city. Assigning the honor of the “first democracy” to Athens is like declaring Abraham Lincoln America’s “first president” because we have more photos of him than we do of George Washington.

Early History of Democracy in Ancient Greece

Demos embodiment being crowned by Democracy from the Agora Museum in Athens

Power was traditionally held by aristocracies, well-connected family, wealthy landlords, despots, military leaders and monarchs. A limited form of democracy first emerged in Babylon, which was ruled by an autocracy but had a popular assembly that made decisions on local affairs while presided over by a royal governor. Forms of democracy also existed in the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon.

In Greece, the city-states were ruled first by local kings or chiefs and then by ruling families while local assemblies were created. At first the assemblies were only advisory bodies. Over time their power grew and they were able to put pressure on the city-state leader and ultimately even select them. Although the assemblies acted somewhat like democratic bodies their members were not democratically elected: they were mostly members of landowning families.

The earliest proto-democracy arose in a climate of war, social chaos and upheaval and was characterized by the people rising up to overthrow a cruel leader. The first so-called firm evidence of this kind of demokratia was documented in Athens in 507 B.C. after a cruel tyrant was assassinated by two gay lovers — Harmodius and Aristogeiton.

In 507 B.C., the Athenian ruler Cleisthenes introduced a new system of “rule by the people.” This is often regarded as the birth of democracy. His system comprised three separate institutions: the ekklesia, which wrote laws; the boule, which heard the representatives of the different tribes; and the dikasteria, which formed the judicial system for Greek citizens. [Source Ward Hazell, Listverse, August 31, 2019]

But evidence has been found that suggests that democracy was introduced decades earlier in the Italian colony of Metapontion, where the tyrant was killed by a young man named Antileon because the tyrant lusted after his male lover. Both men were caught and killed after they were slowed up in their escape by a flock of sheep tied together. After the death of the tyrant statues were erected to honor the lovers and shepherds were forbidden from tying their sheep together while driving them through the streets.

Democracy Takes Hold in Athens

Pericles Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote in for BBC: “It was under this political system that Athens successfully resisted the Persian onslaughts of 490 and 480/79, most conspicuously at the battles of Marathon and Salamis. That victory in turn encouraged the poorest Athenians to demand a greater say in the running of their city, and in the late 460s Ephialtes and Pericles presided over a radicalisation of power that shifted the balance decisively to the poorest sections of society. This was the democratic Athens that won and lost an empire, that built the Parthenon, that gave a stage to Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes, and that laid the foundations of western rational and critical thought. [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, University of Cambridge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The democratic system was not, of course, without internal critics, and when Athens had been weakened by the catastrophic Peloponnesian War (431-404) these critics got their chance to translate word into deed. In 411 and again in 404 Athenian oligarchs led counter-revolutions that replaced democracy with extreme oligarchy. In 404 the oligarchs were supported by Athens's old enemy, Sparta - but even so the Athenian oligarchs found it impossible to maintain themselves in power, and after just a year democracy was restored. |::|

“A general amnesty was declared (the first in recorded history) and - with some notorious 'blips' such as the trial of Socrates - the restored Athenian democracy flourished stably and effectively for another 80 years. Finally, in 322, the kingdom of Macedon which had risen under Philip and his son Alexander the Great to become the suzerain of all Aegean Greece terminated one of the most successful experiments ever in citizen self-government. Democracy continued elsewhere in the Greek world to a limited extent - until the Romans extinguished it for good. |::|

Democracy in Athens

In Athens the assembly had grown powerful enough by around 500 B.C. that it was making laws and electing magistrates. By the Golden Age period the powers of the ruler were limited and day to day affairs were run by a council made of 10 generals. There were no political parties.

Athens during it Golden Age was the home of the world's first democracy and the only polis with a government resembling a true democracy. Although the Athenian government had courts with juries and a political system where rich and poor free men were allowed to vote; women, foreigners, slaves and ex-slaves were not allowed to vote.

Athenian democracy was wild and chaotic and easily hijacked by demagogues. The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt described it as a “permanent terrorism exercised by the combination of sycophant, the or orators and the constant threat of public prosecution, especially for peculation and incompetence." Some historians say that the role of democracy has been exaggerated, and that Athens’ power resulted more from it military victories and money earned from trade than by a government supported by citizens.

Spartan Government

Sparta was one of the greatest city-states of ancient Greece and for a long time the main rival of Athens. Unlike Athens which became a large power by way of trade and naval supremacy, Sparta rose through its military might and bravery. It was said that while Athens was centered around great buildings, Sparta was built by courageous men who “served their city in the place of walls of bricks.”

The Spartan state was considered much more important than the rights and lives of individual citizens. Individual Spartans were regarded as property of the state from the moment they were born and they were expected to give their lives for the state. The Spartan government regimented daily life. Weak babies were left to die, education was like boot camp and marriage was regarded as interruption on the road to comradeship.

Sparta was ruled by two kings, who served jointly, with each acting as a check on the other and their power was checked by the Ephor, a group of five annually elected overseers. The kings served as high priests and led men in war. There was also an assembly, a cabinet-like council of generals and a council of elders.

See Separate Article: SPARTAN STATE, ECONOMY AND GOVERNMENT europe.factsanddetails.com

Greeks Willing to Fight the Mighty Persians Because They Want Freedom

Greeks defeat the Persians at Thermopylae

Herodotus wrote in Book VII of “Histories”: “Then the king's orders were obeyed; and the army marched out between the two halves of the carcase. As Xerxes leads his troops in Greece, he asks a native Greek if the Greeks will put up a fight. Now after Xerxes had sailed down the whole line and was gone ashore, he sent for Demaratus the son of Ariston, who had accompanied him in his march upon Greece, and bespake him thus: "Demaratus, it is my pleasure at this time to ask thee certain things which I wish to know. Thou art a Greek, and, as I hear from the other Greeks with whom I converse, no less than from thine own lips, thou art a native of a city which is not the meanest or the weakest in their land. Tell me, therefore, what thinkest thou? Will the Greeks lift a hand against us? Mine own judgment is, that even if all the Greeks and all the barbarians of the West were gathered together in one place, they would not be able to abide my onset, not being really of one mind. But I would fain know what thou thinkest hereon." [Source: Herodotus “The History of Herodotus” Book VII on the Persian War, 440 B.C., translated by George Rawlinson, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Thus Xerxes questioned; and the other replied in his turn,- "O king! is it thy will that I give thee a true answer, or dost thou wish for a pleasant one?" Then the king bade him speak the plain truth, and promised that he would not on that account hold him in less favour than heretofore. So Demaratus, when he heard the promise, spake as follows: "O king! since thou biddest me at all risks speak the truth, and not say what will one day prove me to have lied to thee, thus I answer. Want has at all times been a fellow-dweller with us in our land, while Valour is an ally whom we have gained by dint of wisdom and strict laws. Her aid enables us to drive out want and escape thraldom. Brave are all the Greeks who dwell in any Dorian land; but what I am about to say does not concern all, but only the Lacedaemonians. First then, come what may, they will never accept thy terms, which would reduce Greece to slavery; and further, they are sure to join battle with thee, though all the rest of the Greeks should submit to thy will. As for their numbers, do not ask how many they are, that their resistance should be a possible thing; for if a thousand of them should take the field, they will meet thee in battle, and so will any number, be it less than this, or be it more."

“When Xerxes heard this answer of Demaratus, he laughed and answered: "What wild words, Demaratus! A thousand men join battle with such an army as this! Come then, wilt thou- who wert once, as thou sayest, their king- engage to fight this very day with ten men? I trow not. And yet, if all thy fellow-citizens be indeed such as thou sayest they are, thou oughtest, as their king, by thine own country's usages, to be ready to fight with twice the number. If then each one of them be a match for ten of my soldiers, I may well call upon thee to be a match for twenty. So wouldest thou assure the truth of what thou hast now said. If, however, you Greeks, who vaunt yourselves so much, are of a truth men like those whom I have seen about my court, as thyself, Demaratus, and the others with whom I am wont to converse- if, I say, you are really men of this sort and size, how is the speech that thou hast uttered more than a mere empty boast? For, to go to the very verge of likelihood- how could a thousand men, or ten thousand, or even fifty thousand, particularly if they were all alike free, and not under one lord- how could such a force, I say, stand against an army like mine? Let them be five thousand, and we shall have more than a thousand men to each one of theirs. If, indeed, like our troops, they had a single master, their fear of him might make them courageous beyond their natural bent; or they might be urged by lashes against an enemy which far outnumbered them. But left to their own free choice, assuredly they will act differently. For mine own part, I believe, that if the Greeks had to contend with the Persians only, and the numbers were equal on both sides, the Greeks would find it hard to stand their ground. We too have among us such men as those of whom thou spakest- not many indeed, but still we possess a few. For instance, some of my bodyguard would be willing to engage singly with three Greeks. But this thou didst not know; and therefore it was thou talkedst so foolishly."

“Demaratus answered him- "I knew, O king! at the outset, that if I told thee the truth, my speech would displease thine ears. But as thou didst require me to answer thee with all possible truthfulness, I informed thee what the Spartans will do. And in this I spake not from any love that I bear them- for none knows better than thou what my love towards them is likely to be at the present time, when they have robbed me of my rank and my ancestral honours, and made me a homeless exile, whom thy father did receive, bestowing on me both shelter and sustenance. What likelihood is there that a man of understanding should be unthankful for kindness shown him, and not cherish it in his heart? For mine own self, I pretend not to cope with ten men, nor with two- nay, had I the choice, I would rather not fight even with one. But, if need appeared, or if there were any great cause urging me on, I would contend with right good will against one of those persons who boast themselves a match for any three Greeks. So likewise the Lacedaemonians, when they fight singly, are as good men as any in the world, and when they fight in a body, are the bravest of all. For though they be free-men, they are not in all respects free; Law is the master whom they own; and this master they fear more than thy subjects fear thee. Whatever he commands they do; and his commandment is always the same: it forbids them to flee in battle, whatever the number of their foes, and requires them to stand firm, and either to conquer or die. If in these words, O king! I seem to thee to speak foolishly, I am content from this time forward evermore to hold my peace. I had not now spoken unless compelled by thee. Certes, I pray that all may turn out according to thy wishes." Such was the answer of Demaratus; and Xerxes was not angry with him at all, but only laughed, and sent him away with words of kindness.”

Decline of Democracy in Athens

Greek general

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote in for BBC: “Not all anti-democrats, however, saw only democracy's weaknesses and were entirely blind to democracy's strengths. One unusual critic is an Athenian writer whom we know familiarly as the 'Old Oligarch'. Certainly, he was an oligarch, but whether he was old or not we can't say. His short and vehement pamphlet was produced probably in the 420s, during the first decade of the Peloponnesian War, and makes the following case: democracy is appalling, since it represents the rule of the poor, ignorant, fickle and stupid majority over the socially and intellectually superior minority, the world turned upside down. [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, University of Cambridge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“By 413, however, the argument from success in favour of radical democracy was beginning to collapse, as Athens' fortunes in the Peloponnesian War against Sparta began seriously to decline. In 411 and again in 404 Athens experienced two, equally radical counter-coups and the establishment of narrow oligarchic regimes, first of the 400 led by the formidable intellectual Antiphon, and then of the 30, led by Plato's relative Critias. Antiphon's regime lasted only a few months, and after a brief experiment with a more moderate form of oligarchy the Athenians restored the old democratic institutions pretty much as they had been. |::|

“It was this revived democracy that in 406 committed what its critics both ancient and modern consider to have been the biggest single practical blunder in the democracy's history: the trial and condemnation to death of all eight generals involved in the pyrrhic naval victory at Arginusae. |::|

“The generals' collective crime, so it was alleged by Theramenes (formerly one of the 400) and others with suspiciously un- or anti-democratic credentials, was to have failed to rescue several thousands of Athenian citizen survivors. Passions ran high and at one point during a crucial Assembly meeting, over which Socrates may have presided, the cry went up that it would be monstrous if the people were prevented from doing its will, even at the expense of strict legality. The resulting decision to try and condemn to death the eight generals collectively was in fact the height, or depth, of illegality. It only hastened Athens' eventual defeat in the war, which was followed by the installation at Sparta's behest of an even narrower oligarchy than that of the 400 - that of the 30.” |::|

“To some extent Socrates was being used as a scapegoat, an expiatory sacrifice to appease the gods who must have been implacably angry with the Athenians to inflict on them such horrors as plague and famine as well as military defeat and civil war. Yet the religious views of Socrates were deeply unorthodox, his political sympathies were far from radically democratic, and he had been the teacher of at least two notorious traitors, Alcibiades and Critias. Nor did he do anything to help defend his own cause, so that more of the 501 jurors voted for the death penalty than had voted him guilty as charged in the first place. By Athenian democratic standards of justice, which are not ours, the guilt of Socrates was sufficiently proven. |::|

“Nevertheless, in one sense the condemnation of Socrates was disastrous for the reputation of the Athenian democracy, because it helped decisively to form one of democracy's - all democracy's, not just the Athenian democracy's - most formidable critics: Plato. His influence and that of his best pupil Aristotle were such that it was not until the 18th century that democracy's fortunes began seriously to revive, and the form of democracy that was then implemented tentatively in the United States and, briefly, France was far from its original Athenian model. If we are all democrats today, we are not - and it is importantly because we are not - Athenian-style democrats. Yet, with the advent of new technology, it would actually be possible to reinvent today a form of indirect but participatory tele-democracy. The real question now is not can we, but should we... go back to the Greeks?

Restoration of Democracy and the Condemnation of Socrates

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote in for BBC: “This, fortunately, did not last long; even Sparta felt unable to prop up such a hugely unpopular regime, nicknamed the '30 Tyrants', and the restoration of democracy was surprisingly speedy and smooth - on the whole. Inevitably, there was some fallout, and one of the victims of the simmering personal and ideological tensions was Socrates. In 399 he was charged with impiety (through not duly recognising the gods the city recognised, and introducing new, unrecognised divinities) and, a separate alleged offence, corrupting the young. | [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, University of Cambridge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024