Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.) / People, Marriage and Society / Government and Justice / Military

SPARTAN STATE

location of Sparta in Greece

Sparta was one of the greatest city-states of ancient Greece and for a long time the main rival of Athens. Unlike Athens which became a large power by way of trade and naval supremacy, Sparta rose through its military might and bravery. It was said that while Athens was centered around great buildings, Sparta was built by courageous men who “served their city in the place of walls of bricks.”

Sparta was in Laconia (on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. In antiquity, it was known as Lacedaemon, while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement on the banks of the Eurotas River in the Eurotas valley of Laconia. Around 650 B.C., it rose to become the dominant military land-power in ancient Greece. [Source Wikipedia]

The Spartan state was considered much more important than the rights and lives of individual citizens. Individual Spartans were regarded as property of the state from the moment they were born and they were expected to give their lives for the state. The Spartan government regimented daily life. Weak babies were left to die, education was like boot camp and marriage was regarded as interruption on the road to comradeship.

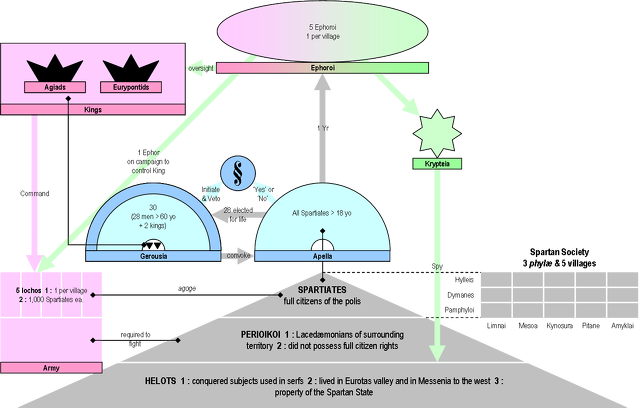

Sparta was ruled by two kings, who served jointly, with each acting as a check on the other and their power was checked by the Ephor, a group of five annually elected overseers. The kings served as high priests and led men in war. There was also an assembly, a cabinet-like council of generals and a council of elders.

Historians have suggested the Spartans were so fierce and brutal because the 8,000 male-citizens were vastly outnumbered by the slaves they controlled. To keep the lower caste intimidated and in line young Spartan men were encouraged to go into the countryside once a year and kill any slaves they saw.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPARTANS: THEIR VALUES, CUSTOMS, CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF SPARTA: ORIGINS, MYTHS, EXPANSION, WARS, DECLINE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTAN MILITARY, TRAINING AND SOLDIER CITIZENS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Spartans: A Very Short Introduction” by Andrew J. Bayliss (2020) Amazon.com;

“On Sparta” by Plutarch (1988) (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by John Lazenby (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by Nicholas Sekunda (1998) Amazon.com;

“Thermopylae: The Battle That Changed the World” by Paul Cartledge (2007)

Amazon.com;

“Gates of Fire” by Steven Pressfield (1998) Novel Amazon.com;

“300" DVD Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy” by Myke Cole (2021) Amazon.com;

“Sparta: Fall of a Warrior Nation” by Philip Matyszak (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sparta: Fall of a Warrior Nation” by Philip Matyszak (2018) Amazon.com;

“Spartan History: Legends, Mysteries, and Curiosities” by VC Brothers (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education & Culture in Ancient Sparta” by Nigel M. Kennell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Spartan Women” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (2002) Amazon.com;

“Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta” by Stephen Hodkinson (2000) Amazon.com;

“Leonidas of Sparta: A Boy of the Agoge” by Helena P Schrader (2010), Novel Amazon.com;

“Axios: A Spartan Tale” by Jaclyn Osborn (2017), Novel Amazon.com;

“Spartans at the Gates: A Novel” by Noble Smith (2014) Amazon.com;

Spartan Economy and Frugality

Cristian Violatti wrote in Listverse: The pursuit of material wealth and mostly any other activity outside of a military career was discouraged by Spartan law. Iron was the only metal allowed for coinage; gold and silver were forbidden. According to Plutarch (“Life of Lycurgus”: 9), Spartans had their coins made of iron. Therefore, a small value required a great weight and volume of coins.Transporting a significant amount of value in coins required the use of a team of oxen, and storing it needed a large room. This made bribery and stealing difficult in Sparta. Wealth was not easy to enjoy and almost impossible to hide. [Source by Cristian Violatti, Listverse, August 3, 2016]

Spartans were absolutely debarred by law from trade or manufacture, which consequently rested in the hands of the perioeci (q.v.), and were forbidden to possess either gold or silver, the currency consisting of bars of iron: but there can be no doubt that this prohibitian was evaded in various ways. Wealth was, in theory at least, derived entirely from landed property, and consisted in the annual return made by the helots (q.v.) who cultivated the plots of ground allotted to the Spartans. But this attempt to equalize property proved a failure: from early times there were marked differences of wealth within the state, and these became even more serious after the law of epitadeus, passed at some time after the Peloponnesian War, removed the legal prohibition of the gift or bequest of land. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911 Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Later we find the soil coming more and more into the possession of large landholders, and by the middle of the 3rd century B.C. nearly two fifths of Laconia belonged to women. Hand in hand with this process went a serious diminution in the number of full citizens, who had numbered 8000 at the beginning of the 5th century, but had sunk by Aristotle's day to less than 1000, and had further decreased to 700 at the accession of Agis IV. in 244 B.C. The Spartans did. what they could to remedy this by law: certain penalties were imposed upon those who remained unmarried or who married too late in life. But the~decay was too deep-rooted to be eradicated by such means, and we shall see that at a late period in Sparta's history an attempt was made without success to deal with the evil by much more drastic measures.”

Xenophon: The Polity of the Spartans

Xenophon was a great admirer of the Spartans. In “The Polity of the Spartans” (c. 375 B.C.), he wrote: “I recall the astonishment with which I first noted the unique position of Sparta among the states of Hellas, the relatively sparse population, and at the same time the extraordinary powers and prestige of the community. I was puzzled to account for the fact. It was only when I came to consider the peculiar institutions of the Spartans, that my wonderment ceased. [Source: Xenophon, “The Polity of the Spartans” (c. 375 B.C.) Fred Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 66-75.]

“When we turn to Lycurgos, instead of leaving it to each member of the state privately to appoint a slave to be his son's tutor, he set over the young Spartans a public guardian — the paidonomos — with complete authority over them. This guardian was elected from those who filled the highest magistracies. He had authority to hold musters of the boys, and as their guardian, in case of any misbehavior, to chastise severely. Lycurgos further provided the guardian with a body of youths in the prime of life and bearing whips to inflict punishment when necessary, with this happy result, that in Sparta modesty and obedience ever go hand in hand, nor is there lack of either.

ruins of ancient Sparta “Instead of softening their feet with shoe or sandal, his rule was to make them hardy through going barefoot. This habit, if practiced, would, as he believed, enable them to scale heights more easily and clamber down precipices with less danger. In fact, with his feet so trained the young Spartan would leap and spring and run faster unshod than another in the ordinary way. Instead of making them effeminate with a variety of clothes, his rule was to habituate them to a single garment the whole year through, thinking that so they would be better prepared to withstand the variations of heat and cold. Again, as regards food, according to his regulation, the eiren, or head of the flock, must see that his messmates gather to the club meal with such moderate food as to avoid bloating and yet not remain unacquainted with the pains of starvation. His belief was that by such training in boyhood they would be better able when occasion demanded to continue toiling on an empty stomach....On the other hand, to guard against a too great pinch of starvation, he did give them permission to steal this thing or that in the effort to alleviate their hunger.

“Lycurgos imposed upon the bigger boys a special rule. In the very streets they were to keep their two hands within the folds of their coat; they were to walk in silence and without turning their heads to gaze, now here, now there, but rather to keep their eyes fixed upon the ground before them. And hereby it would seem to be proved conclusively that, even in the matter of quiet bearing and sobriety, the masculine type may claim greater strength than that which we attribute to the nature of women. At any rate, you might sooner expect a stone image to find voice than one of these Spartan youths...

“When Lycurgos first came to deal with the question, the Spartans, like the rest of the Hellenes, used to mess privately at home. Tracing more than half the current problems to this custom, he was determined to drag his people out of holes and corners into the broad daylight, and so he invented the public mess rooms. As to food, his ordinance allowed them only so much as should guard them from want.....So that from beginning to end, till the mess breaks up, the common board is never stinted for food nor yet extravagantly furnished. So also in the matter of drink. While putting a stop to all unnecessary drink, he left them free to quench thirst when nature dictated.....Thus there is the necessity of walking home when a meal is over, and a consequent anxiety not to be caught tripping under the influence of wine, since they all know of course that the supper table must be presently abandoned and that they must move as freely in the dark as in the day, even with the help of a torch.

“It is clear that Lycurgos set himself deliberately to provide all the blessings of heaven for the good man, and a sorry and ill-starred existence for the coward. In other states the man who shows himself base and cowardly, wins to himself an evil reputation and the nickname of a coward, but that is all. For the rest he buys and sells in the same marketplace with a good man; he sits beside him at a play; he exercises with him in the same gymnasion, and all as suits his humor. But at Sparta there is not one man who would not feel ashamed to welcome the coward at the common mess-tables or to try conclusions with him in a wrestling bout;....during games he is left out as the odd man;....during the choric dance he is driven away. Nay, in the very streets it is he who must step aside for others to pass, or, being seated, he must rise and make room, even for a younger man....

Sparta

“Lycurgos also provided for the continual cultivation of virtues even to old age, by fixing the election to the council of elders as a last ordeal at the goal of life, thus making it impossible for a high standard of virtuous living to be disregarded even in old age....Moreover he laid upon them, like some irresistible necessity, the obligation to cultivate the whole virtue of a citizen. Provided they duly perform the injunctions of the law, the city belonged to them each and all, in absolute possession, and on an equal footing....

“I wish to explain with sufficient detail the nature of the covenant between king and state as instituted by Lycurgos; for this, I take it, is the sole type of rule which still preserves the original form in which it was first established; whereas other constitutions will be found either to have been already modified or else to be still undergoing modification at this moment. Lycurgos laid it down as law that the king shall offer on behalf of the state all public sacrifices, as being himself of divine descent, and wherever the state shall dispatch her armies the king shall take the lead. He granted him to receive honorary gifts of the things offered in sacrifice, and he appointed him choice land in many of the provincial cities, enough to satisfy moderate needs without excess of wealth. And in order that the kings might also encamp and mess in public he appointed them public quarters, and he honored them with a double portion each at the evening meal, not in order that they might actually eat twice as much as others, but that the king might have the means to honor whomsoever he wished. He also granted as a gift to each of the two kings to choose two mess-mates, which are called tuthioi. He also granted them to receive out of every litter of swine one pig, so that the king might never be at a loss for victims if he wished to consult the gods.

“Close by the palace a lake affords an unrestricted supply of water; and how useful that is for various purposes they best can tell who lack the luxury. Moreover, all rise from their seats to give place to the king, save only that the ephors rise not from their throne of office. Monthly they exchange oaths, the ephors on behalf of the state, the king himself on his own behalf. And this is the oath on the king's part: "I will exercise my kingship in accordance with the established laws of the state." And on the part of the state (the ephors) the oath runs: "So long as he (who exercises kingship), shall abide by his oath we will not suffer his kingdom to be shaken."

Spartan Government

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “Of the internal development of Sparta” to the 6th century B.C. “little is recorded. This want of information was attributed by most of the Greeks to the stability of the Spartan constitution, which had lasted unchanged from the days of Lycurgus. But it is, in fact, due also to the absence of an historical literature at Sparta, to the small part played by written laws, which were, according to tradition, expressly prohibited by an ordinance of Lycurgus, and to the secrecy which always characterizes an oligarchical rule. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, 1911 Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“At the head of the state stood two hereditary kings, of the Agiad and Eurypontid families, equal in authority, so that one could not act against the veto of his colleague, though the Agiad king received greater honour in virtue of the seniority of his family (Herod. vi. 51), This dual kingship, a phenomenon unique in Greek history, was explained in Sparta by the tradition that on Aristodemus's death he had been succeeded by his twin sons, and that this joint rule had been perpetuated. Modern scholars have advanced various theories to account for the anomaly. Some suppose that it must be explained as an attempt to avoid absolutism, and is paralleled by the analogous instance of the consuls at Rome. Others think that it points bo a compromise arrived at to end the struggle between two families or communities, or that the two royal houses represent respectively the Spartan conquerors and their Achaean predecessors: those who hold this last view appeal to the words attributed by Herodotus (v. 72) to Cleomenes I.: "I am no Dorian, but an Achaean."

“The duties of the kings were mainly religious,. judicial and military. They were the chief priests of the state, and had to perform certain sacrifices and to maintair~ communication with the Delphian sanctuary, which always exercised great authority in Spartan politia. Their judicial functions hafl at the time when Herodotus wrote (about 430 B.C.) Been restricted to cases dealing with heir~ises, adoptions and the public roads: civil cases were decided by the ephors, criminal jurisdiction had passed to the council of elders and the ephors. It was in the military sphere that the powers of the kings were most unrestricted. Aristotle describes the kingship at Sparta as "a kind of unlimited and perpetual generalship " (Pol. iii. 1285a), while Isocrates refers to the Spartans as "subject to an oligarchy at home, to a kingship on campaign" (iii. 24). Here also, however, the royal prerogatives were curtailed in course of time: from the period of the Persian wars the king lost the right of declaring war on whom he pleased, he was accompanied to the field by two ephors, and he was supplanted also by the ephors in the control of foreign policy.

“More and more, as time went on, the kings became mere figureheads, except in their capacity as generals, and the real power was trarlsferred to the ephors and to the gerousia (q.v.). The reason for this change lay partly in the fact that the ephors, chosen by popular election from the whole body of citizer~, represented a democratic element in the constitution wihthout violating those oligarchical methods which seemed necessary for its satisfactory administration; partly in the weakness of the kingship, the dual character of which inevitably gave rise to jealousy and discord between the two holders of the office, often resulting in a practical deadlock; partly in the loss of prestige suffered by the kingship, especially during the sth century, owing to these quarrels, to the frequency with which kings ascended the throne as minors and a regency was riecessary, and to the many cases in which a king was, rightly or wrongly, suspected of having accepted bribes from the enemies of the state and was condemned and banished.”

Spartan Kings and the Ephors

Cristian Violatti wrote in Listverse: Sparta had two kings belonging to different royal dynasties. Although their power was limited, one of them would have the duty of commanding the army in time of war. Spartan kings were descendants of the god Heracles. At least, this is what the official genealogy of the Spartan kings claimed.The existence of two ruling houses was in direct contradiction with the idea of a common ancestry, which led to an imaginative explanation: During the fifth generation after Heracles, twin sons, Agis and Eurypon, had been born to the king. This was the mythical origin of the ruling families’ names, the Agiads and the Eurypontids.Herodotus offers a complete genealogical list for the ancestry of Leonidas and Leotychidas, the two Spartan kings around the time of the Persian Wars. (Histories: 7.204.480 for Leonidas and 8.131.2 for Leotychidas). [Source by Cristian Violatti, Listverse, August 3, 2016]

The ephors were a branch of Spartan government with no equivalent in the rest of the Greek world. They were elected annually from the pool of male citizens. Their role was to balance and complement the role of the king. They were the supreme civil court and had criminal jurisdiction over the king.The kings swore to uphold the Spartan constitution, and the ephors swore to uphold the king as long as he kept his oath. When a king went to war, two of the ephors would join him to supervise his actions. During the absence of a king, some of his responsibilities would be delegated to the ephors.

Demaratus and the Spartan Concept of Freedom

The 5th century B.C. Greek historian Herodotos presented a dialogue between Demaratos (a Greek) and Xerxes, Emperor of Persia. Herodotos tried to make clear the difference between people ruled by an autocratic Emperor and people ruled by laws. Herodotus argued that austere Sparta is to be preferred to the wealthy and powerful empire of the Persians. Elaborating on this point, William McNeill argued that, instead of tribal, aristocratic or ties of King and Empire, it was "territorial" politics that defined the Greeks and lent a unique, significant aspect to Western Civilization. In his dialogue with Xerxes, Demaratus seems to support McNeill's contention.

Demaratus was an exiled King of Sparta who became a counsellor to Xerxes. His speech also shows the concept of Spartan excellence. As a part of it, for example, Demaratos mentioned that Spartans thought of themselves as "free men." But what, exactly, is this 'Spartan freedom'? Xerxes sent for Demaratus the son of Ariston, who had accompanied him in his march upon Greece, and said to him: "Demaratus, I would like you to tell me something. As I hear, you are a Greek and a native of a powerful city. Tell me, will the Greeks really fight against us? I think that even if all the Greeks and all the barbarians of the West were gathered together in one place, they would not be able to stop me, since they are so disunited. But I would like to know what you think about this."

Demaratus replied to Xerxes' question: "O king! Do you really want me to give a true answer, or would you rather that I make you feel good about all this?" The king commanded him to speak the plain truth, and promised that he would not on that account hold him in less favor than before. When he heard this promise, Demaratus spoke as follows: "O king! Since you command me to speak the truth, I will not say what will one day prove me a liar. Difficulties have at all times been present in our land, while Courage is an ally whom we have gained through wisdom and strict laws. Her aid enables us to solve problems and escape being conquered. All Greeks are brave, but what I am about to say does not concern all, but only the Spartans."

"First then, no matter what, the Spartans will never accept your terms. This would reduce Greece to slavery. They are sure to join battle with you even if all the rest of the Greeks surrendered to you. As for Spartan numbers, do not ask how many or few they are, hoping for them to surrender. For if a thousand of them should take the field, they will meet you in battle, and so will any other number, whether it is less than this, or more."

The Selection of the Spartan Infant by Giuseppe Diotti

Aristotle: The Spartan Constitution from the Politics

On the Lacedaemonian (Spartan) Constitution, Aristotle wrote in “Politics” (c. 340 B.C.): “The Cretan constitution nearly resembles the Spartan, and in some few points is quite as good; but for the most part less perfect in form. The older constitutions are generally less elaborate than the later, and the Lacedaemonian is said to be, and probably is, in a very great measure, a copy of the Cretan. According to tradition, Lycurgus, when he ceased to be the guardian of King Charillus, went abroad and spent most of his time in Crete. For the two countries are nearly connected; the Lyctians are a colony of the Lacedaemonians, and the colonists, when they came to Crete, adopted the constitution which they found existing among the inhabitants. . . .The Cretan institutions resemble the Lacedaemonian. The Helots are the husbandmen of the one, the Perioeci of the other, and both Cretans and Lacedaemonians (Spartans) have common meals, which were anciently called by the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) not phiditia' but andria'; and the Cretans have the same word, the use of which proves that the common meals originally came from Crete. Further, the two constitutions are similar; for the office of the Ephors is the same as that of the Cretan Cosmi, the only difference being that whereas the Ephors are five, the Cosmi are ten in number. The elders, too, answer to the elders in Crete, who are termed by the Cretans the council. And the kingly office once existed in Crete, but was abolished, and the Cosmi have now the duty of leading them in war. All classes share in the ecclesia, but it can only ratify the decrees of the elders and the Cosmi. [Source: Aristotle, “The Politics of Aristotle,” translated by Benjamin Jowett (London: Colonial Press, 1900), pp. 30-49]

“The common meals of Crete are certainly better managed than the Lacedaemonian; for in Lacedaemon (Sparta) every one pays so much per head, or, if he fails, the law, as I have already explained, forbids him to exercise the rights of citizenship. But in Crete they are of a more popular character. There, of all the fruits of the earth and cattle raised on the public lands, and of the tribute which is paid by the Perioeci, one portion is assigned to the Gods and to the service of the state, and another to the common meals, so that men, women, and children are all supported out of a common stock. The legislator has many ingenious ways of securing moderation in eating, which he conceives to be a gain; he likewise encourages the separation of men from women, lest they should have too many children, and the companionship of men with one another---whether this is a good or bad thing I shall have an opportunity of considering at another time. But that the Cretan common meals are better ordered than the Lacedaemonian there can be no doubt. On the other hand, the Cosmi are even a worse institution than the Ephors, of which they have all the evils without the good. Like the Ephors, they are any chance persons, but in Crete this is not counterbalanced by a corresponding political advantage. At Sparta every one is eligible, and the body of the people, having a share in the highest office, want the constitution to be permanent. But in Crete the Cosmi are elected out of certain families, and not out of the whole people, and the elders out of those who have been Cosmi.

“Some, indeed, say that the best constitution is a combination of all existing forms, and they praise the Lacedaemonian because it is made up of oligarchy, monarchy, and democracy, the king forming the monarchy, and the council of elders the oligarchy while the democratic element is represented by the Ephors; for the Ephors are selected from the people. Others, however, declare the Ephoralty to be a tyranny, and find the element of democracy in the common meals and in the habits of daily life. At Lacedaemon, for instance, the Ephors determine suits about contracts, which they distribute among themselves, while the elders are judges of homicide, and other causes are decided by other magistrates.

Problems with the Spartan Constitution According to Aristotle

On some defects in the Spartan Constitution, Aristotle wrote in “Politics” (c. 340 B.C.): “There is a tradition that, in the days of their ancient kings, they were in the habit of giving the rights of citizenship to strangers, and therefore, in spite of their long wars, no lack of population was experienced by them; indeed, at one time Sparta is said to have numbered not less than 10,000 citizens Whether this statement is true or not, it would certainly have been better to have maintained their numbers by the equalization of property. Again, the law which relates to the procreation of children is adverse to the correction of this inequality. For the legislator, wanting to have as many Spartans as he could, encouraged the citizens to have large families; and there is a law at Sparta that the father of three sons shall be exempt from military service, and he who has four from all the burdens of the state. Yet it is obvious that, if there were many children, the land being distributed as it is, many of them must necessarily fall into poverty. [Source: Aristotle, “The Politics of Aristotle,” translated by Benjamin Jowett (London: Colonial Press, 1900), pp. 30-49]

“The Lacedaemonian constitution is defective in another point; I mean the Ephoralty. This magistracy has authority in the highest matters, but the Ephors are chosen from the whole people, and so the office is apt to fall into the hands of very poor men, who, being badly off, are open to bribes. There have been many examples at Sparta of this evil in former times; and quite recently, in the matter of the Andrians, certain of the Ephors who were bribed did their best to ruin the state. And so great and tyrannical is their power, that even the kings have been compelled to court them, so that, in this way as well together with the royal office, the whole constitution has deteriorated, and from being an aristocracy has turned into a democracy. The Ephoralty certainly does keep the state together; for the people are contented when they have a share in the highest office, and the result, whether due to the legislator or to chance, has been advantageous. For if a constitution is to be permanent, all the parts of the state must wish that it should exist and the same arrangements be maintained. This is the case at Sparta, where the kings desire its permanence because they have due honor in their own persons; the nobles because they are represented in the council of elders (for the office of elder is a reward of virtue); and the people, because all are eligible to the Ephoralty. The election of Ephors out of the whole people is perfectly right, but ought not to be carried on in the present fashion, which is too childish. Again, they have the decision of great causes, although they are quite ordinary men, and therefore they should not determine them merely on their own judgment, but according to written rules, and to the laws. Their way of life, too, is not in accordance with the spirit of the constitution — they have a deal too much license; whereas, in the case of the other citizens, the excess of strictness is so intolerable that they run away from the law into the secret indulgence of sensual pleasures.

“Again, the council of elders is not free from defects. It may be said that the elders are good men and well trained in manly virtue; and that, therefore, there is an advantage to the state in having them. But that judges of important causes should hold office for life is a disputable thing, for the mind grows old as well as the body. And when men have been educated in such a manner that even the legislator himself cannot trust them, there is real danger. Many of the elders are well known to have taken bribes and to have been guilty of partiality in public affairs. And therefore they ought not to be irresponsible; yet at Sparta they are so. But (it may be replied), 'All magistracies are accountable to the Ephors.' Yes, but this prerogative is too great for them, and we maintain that the control should be exercised in some other manner. Further, the mode in which the Spartans elect their elders is childish; and it is improper that the person to be elected should canvass for the office; the worthiest should be appointed, whether he chooses or not. And here the legislator clearly indicates the same intention which appears in other parts of his constitution; he would have his citizens ambitious, and he has reckoned upon this quality in the election of the elders; for no one would ask to be elected if he were not. Yet ambition and avarice, almost more than any other passions, are the motives of crime.

“Whether kings are or are not an advantage to states, I will consider at another time; they should at any rate be chosen, not as they are now, but with regard to their personal life and conduct. The legislator himself obviously did not suppose that he could make them really good men; at least he shows a great distrust of their virtue. For this reason the Spartans used to join enemies with them in the same embassy, and the quarrels between the kings were held to be conservative of the state.

“Neither did the first introducer of the common meals, called 'phiditia,' regulate them well. The entertainment ought to have been provided at the public cost, as in Crete; but among the Lacedaemonians every one is expected to contribute, and some of them are too poor to afford the expense; thus the intention of the legislator is frustrated. The common meals were meant to be a popular institution, but the existing manner of regulating them is the reverse of popular. For the very poor can scarcely take part in them; and, according to ancient custom, those who cannot contribute are not allowed to retain their rights of citizenship.

“The law about the Spartan admirals has often been censured, and with justice; it is a source of dissension, for the kings are perpetual generals, and this office of admiral is but the setting up of another king. The charge which Plato brings, in the Laws, against the intention of the legislator, is likewise justified; the whole constitution has regard to one part of virtue only — the virtue of the soldier, which gives victory in war. So long as they were at war, therefore, their power was preserved, but when they had attained empire they fell for of the arts of peace they knew nothing, and had never engaged in any employment higher than war. There is another error, equally great, into which they have fallen. Although they truly think that the goods for which men contend are to be acquired by virtue rather than by vice, they err in supposing that these goods are to be preferred to the virtue which gains them.

“Once more: the revenues of the state are ill-managed; there is no money in the treasury, although they are obliged to carry on great wars, and they are unwilling to pay taxes. The greater part of the land being in the hands of the Spartans, they do not look closely into one another's contributions. The result which the legislator has produced is the reverse of beneficial; for he has made his city poor, and his citizens greedy. Enough respecting the Spartan constitution, of which these are the principal defects.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024