Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.)

ANCIENT GREEK CLASSICAL AGE (500 B.C. TO 323 B.C.)

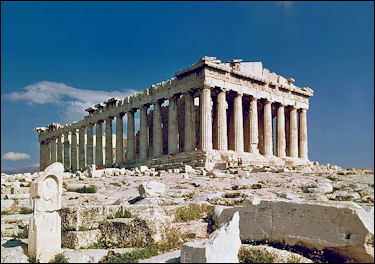

Parthenon in Athens The Greek Classical Age began with Greece's wars the defeat of the second Persian invasion in 479 B.C., and ended with the establishment of Macedonian power in 338 B.C. and Alexander's march of conquest through the Middle East and Asia. The warring city-states that made up ancient Greece flourished as centers of trade. Athens, the most wealthy and powerful, developed a democratic system under the leadership of Pericles. Its main rival was the military state of Sparta. Classical Greece was the birthplace of many ideas in art, literature, philosophy and science. Perhaps the most famous purveyors of these ideas were Plato and Aristotle. Ancient Greece has traditionally been regarded as the birthplace of Western civilization.

Politically Greece was never unified like the Roman empire. What bound the Greeks together was culture, architecture, sculpture, drama and music. Rugged mountain ranges and numerous bodies of water divided the civilization into individual city-states that existed in valleys and on islands and peninsulas. Roads and waterways made the sharing of culture possible, but the natural barriers made each city-state autonomous politically and agriculturally. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

When the Greeks emerged as a significant civilization, the Persians were far and away the most dominant culture and military power in the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean. The Greeks were still unified city-states. What united the Greeks militarily was their willingness to fight together against the Persians.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Greek World, 479-323 BC” by Simon Hornblower (1983) Amazon.com;

“Classical Greeks” by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“A Chronology of Ancient Greece” by Timothy Venning (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and Greek Civilization” by Jacob Burckhardt (1902) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks” by H. Kitto (Penguin History) (Six books) Amazon.com;

“Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization” by Simon Hornblowwer and Anthony Spawforth Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1998) Amazon.com;

“Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece” by Robin Waterfield (2018) Amazon.com;

“Democracy: A Life” by Paul Cartledge (2016) Amazon.com;

“Athens, A Portrait of a City in Its Golden Age by Christian Meier” (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holy & Company, 1998) Amazom.com

“Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy” by John R. Hale (2009) Amazon.com;

“ The Rise of Athens: The Story of the World's Greatest Civilization” by Anthony Everitt (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” by Plutarch (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek City States

Ancient Greece was divided in “polises” , or city-states, which were neither cities or states. They were self sufficient communities with their own army, customs and laws. Each polis contained one town, which was also the center of the government. The first true city states have been traced to Dorian settlements (850-750 B.C.) on Crete, where constitutions were drawn up that granted certain rights to the Dorian conquerors but denied them to everybody else. Between 750 and 500 B.C. chiefdoms and villages coalesced into city-states on the Greek mainland, Aegean islands and Asia.

Cavalcade frieze on the Parthenon Many city-states were centered around citadels built on mounds or hills (an acropolis) hills for protection. Within the settlement were houses, an “ agora” , or marketplace, and temples for worshiping. Their authority often spread no further that the surrounding plains or valley. The historian Daniel Boorstin wrote, they were "just large enough and just small enough, neither wholly urban nor wholly rural, for it needed both countryside and city...The polis strictly speaking consisted not of the territory but of the citizens....there were several hundred such Greek polis so varied that general history of them is not possible."

The polis had a “religion-like importance.” Different city-states had different forms of government. Many began as oligarchies ruled by land-owning aristocrats. Most had councils made up of male citizens that made laws. Some suggest that temples with large central room may have been used for political as well as religious assemblies. As the “ demos” , or people, gained more say, democracies arose, most famously in Athens.

See Separate Article: POWERFUL CITY STATES OF ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Athens

In the golden age of Athens and the Greece in the 5th century B.C. Athens was the heart of the classical Greek civilization and a pioneer of democracy. In 3rd and 4th centuries B.C. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle addressed their followers in markets ans academies and tragedies by Sophocles and Aristhosenes were performed in the amphitheaters. The acropolis was the center of the ancient city. Other classical building are buried beneath the modern city where they are occasionally unearthed by sewer and subway construction workers.

Ancient Athens was claimed according to legend by the goddess Athena after she defeated the sing king Poseidon in an epic battle. The first settlement of Athens, dated to around 3000 B.C. was situated on the rock of Acropolis. By 1400 BC the settlement had become an important center of the Mycenaean civilization and the Acropolis was the site of a major Mycenaean fortress whose remains can be recognised from sections of the characteristic Cyclopean walls. Unlike other Mycenaean centers, such as Mycenae and Pylos, we do not know whether Athens suffered destruction in about 1200 BC, an event often attributed to a Dorian invasion, and the Athenians always maintained that they were "pure" Ionians with no Dorian element. However, Athens, like many other Bronze Age settlements, went into economic decline for around 150 years following this.

Ancient Athens was claimed according to legend by the goddess Athena after she defeated the sing king Poseidon in an epic battle. The first settlement of Athens, dated to around 3000 B.C. was situated on the rock of Acropolis. By 1400 BC the settlement had become an important center of the Mycenaean civilization and the Acropolis was the site of a major Mycenaean fortress whose remains can be recognised from sections of the characteristic Cyclopean walls. Unlike other Mycenaean centers, such as Mycenae and Pylos, we do not know whether Athens suffered destruction in about 1200 BC, an event often attributed to a Dorian invasion, and the Athenians always maintained that they were "pure" Ionians with no Dorian element. However, Athens, like many other Bronze Age settlements, went into economic decline for around 150 years following this.

Before the concept of the political state arose, four tribes based upon family relationships dominated the area. The members had certain rights, privileges, and obligations including common religious rights, a common burial place and mutual rights of succession to property of deceased members. During this period, Athens succeeded in bringing the other towns of Attica under its rule. This process of synoikismos — the bringing together into one home — created the largest and wealthiest state on the Greek mainland, but it also created a larger class of people excluded from political life by the nobility. By the 7th century BC social unrest had become widespread, and the Areopagus appointed Draco to draft a strict new code of law (hence the word 'draconian'). When this failed, they appointed Solon, with a mandate to create a new constitution (in 594 BC). [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ATHENS europe.factsanddetails.com

Golden Age of Greece

The Golden Age of Greece was during the rule of Pericles over Athens from 457 B.C. to 430 B.C. During this time the Parthenon was built, Aeschylus, Aristophanes and Sophocles were producing plays in the theater beside the Acropolis and democracy flourished. Pericles ruled over what has been described as the world's first democracy and mathematics, the arts, history, astronomy and philosophy flourished under Socrates, the Sophists, Herodotus and Thucydides.

During the Golden Age of Greece Athens was home to about 75,000 people and and between 200,000 and 250,000 lived in the surrounding countryside called "Attica." The city had an area of about 0.7 square miles.

Under Athens and the Delian League the Greeks ruled much of the Mediterranean and trade flourished. Using iron to make tools, superior ships, weapons and machines Athens grew rich by exporting silver and olives. The money earned from this trade was used to construct other great building and support the arts and sciences.

But thing are not always as rosy as the seemed on the surface. A lot of the money used to build the Parthenon was looted from the Delios League treasury, less than a quarter of the population had political rights, slaves were often used instead of machines because they were cheaper, and war with Sparta was imminent. The upper classes ruled the government and many of the democratic reforms, such as payment for jury duty, were attempts to placate the lower classes with welfare payments and keep them in place. In the plains of Attica there only about 250,000 people. The population of the city-state of Athens had would later be reduced by the Peloponnesian wars and the plague from around 80,000 to as a low as 21,000.◂

Book: “ Athens, A Portrait of a City in Its Golden Age” by Christian Meier (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holy & Company, 1998]

Pericles

Pericles

Pericles (490-429 B.C.) ruled over what has been described as the world's first democracy. Although he never claimed the highest title, archon , and described himself simply as one of the ten generals elected each year by the citizenry he was firmly in control during his 27 year rule over Athens and owed his position to his will, charisma and oratory skills. He was the model for the tyrant Creon who condemns Antigone to death and for Oedipus the King.

Pericles instituted for public service, which expanded the realm of democracy, and looked after the welfare of the Athenian poor. But he also made Athens broke by diverted much of the money from the Delian League to finance the construction of Parthenon and other monumental structures.

Pericles was a nobleman with “the bluest blood” and came from one of the wealthiest Athens families. Despite this he was popular with ordinary Athenians and had the rhetorical skills to talk them in doing almost anything. He reportedly had big ears. Images of him show his big ears under a helmet. Pericles was Athens most brilliant statesmen and orator and he seemed know it. He said, "The admiration of the present and succeeding ages will be ours."

See Separate Article: PERICLES: HIS LIFE, SPEECHES AND IMPACT ON ANCIENT ATHENS AND GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Democracy

The ancient Greeks are credited with founding democracy (a word derived from Greek words for people, “demos” , and “ kratos” , rule) and literally means “rule by the people.” In the early days most city-states, however, were ruled by local tyrants or oligarchies that formed citizen councils. The philosopher Democritus had nothing really to do with democracy. He is known for his theory on atoms.

Pericles wrote: "Our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands of the people, not a minority. When it is a question of settling private disputes, everybody is equal before the law; when it is a question of putting one person before another in positions of public responsibility, what counts is not membership of a particular class, but the actual ability which the man possesses. No one, so long as he has it in him to be of service to the state, is kept in political obscurity because of poverty...This is a peculiarity of ours: we do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has not business here at all.

Plato once wrote democracy is a "delightful form of government, anarchic and motley." Some scholars have argued that democracy took root because citizens were more interested in success than domination. They were interested in impressing an audience or cutting a stylish figure than real power. There were few political institutions and the powers of persuasion held sway. Men had prove themselves in front of other men rather than hiding behind a birthrate or a title.

See Separate Article: GOVERNMENT IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; DEMOCRACY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; MAJOR FIGURES IN ANCIENT GREEK DEMOCRACY europe.factsanddetails.com

Democracy in Athens

Voting scene In Athens the assembly had grown powerful enough by around 500 B.C. that it was making laws and electing magistrates. By the Golden Age period the powers of the ruler were limited and day to day affairs were run by a council made of 10 generals. There were no political parties.

Athens during it Golden Age was the home of the world's first democracy and the only polis with a government resembling a true democracy. Although the Athenian government had courts with juries and a political system where rich and poor free men were allowed to vote; women, foreigners, slaves and ex-slaves were not allowed to vote.

Athenian democracy was wild and chaotic and easily hijacked by demagogues. The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt described it as a “permanent terrorism exercised by the combination of sycophant, the or orators and the constant threat of public prosecution, especially for peculation and incompetence." Some historians say that the role of democracy has been exaggerated, and that Athens’ power resulted more from it military victories and money earned from trade than by a government supported by citizens.

Greek Colonies

The Greeks traded all over the Mediterranean with metal coinage (introduced by the Lydians in Asia Minor before 700 B.C.); colonies were founded around the Mediterranean and Black Sea shores (Cumae in Italy 760 B.C., Massalia in France 600 B.C.) “ Metropleis” (mother cities) founded colonies abroad to provide food and resources for their rising populations. In this way Greek culture was spread to a fairly wide area. ↕

Beginning in the 8th century B.C., the Greeks set up colonies in Sicily and southern Italy that endured for 500 years, and, many historians argue, provided the spark that ignited Greek golden age. The most intensive colonization took place in Italy although outposts were set up as far west as France and Spain and as far east as the Black Sea, where the established cities as Socrates noted like "frogs around a pond." On the European mainland, Greek warriors encountered the Gauls who the Greeks said "knew how to die, barbarians though they were.” [Source: Rick Gore, National Geographic, November 1994]

During this period in history the Mediterranean Sea was frontier as challenging to the Greeks as the Atlantic was to 15th century European explorers like Columbus. Why did the Greeks head west? "They were driven in part by curiosity,” a British historian told National Geographic. "Real curiosity. They wanted to know what lay on the other side of the sea." They also expanded abroad to get rich and ease tensions at home where rival city-states fought with one another over land and resources. Some Greeks became quite wealthy trading things like Etruscan metals and Black Sea grain.

In 480 B.C., Greek colonists defeated an invading army of Carthaginians near Himera on Sicily’s northern coast. According to Archaeology magazine: The victory was hailed by ancient Greek historians such as Herodotus as a triumph of the Greek spirit. However, a new study reveals that the Greeks had help. Genetic and isotope analysis of the remains of soldiers who perished in the conflict surprisingly indicated that a number were foreigners, recruited by the Greeks as mercenaries from as far away as the Baltic Sea region and the Eurasian steppe. [Source: Archaeology magazine January 2023]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK COLONIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Delian League and the Payment of Tribute Money to Athens

Concerned about further attacks by Persia, 200 Greek city-states formed an Athens-led alliance called the Delian League (sometimes also called the Delios League) in 478 B.C. In exchange for money or ships, Athens fleet of ships evicted the Persians, cleared out pirates and secured trade access to the Black Sea. As Athens’ power grew other city states resented their position as "subjects."

Named after the site of it headquarters, the sacred island of Delos, the Delian League was essentially a organization set up for city states to pay tribute money to Athens in exchange for protection. The arrangement wasn’t all that different from protection money paid by businesses to organized gangs.

With this money Athens beefed up its navy, making it even stronger, and embarked on expensive building campaigns such as the construction of the Acropolis and the building of the Parthenon. Surviving fragments of financial accounts, which were inscribed on stone for the public to see estimate the construction budget of the Parthenon to be 340 to 800 silver talents — a considerable sum at a time when a single talent could be a month’s wage for a 170 oarsmen on a Greek warship.

See 11th Brittanica: Delian League, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University sourcebooks.web.fordham.edu

Peloponnese League

The Delain League was preceded by the Peloponnesian League, a Sparta-dominated alliance in the Peloponnesus that existed from the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C.. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), against the Delian League, which was dominated by Athens. [Source: Wikipedia +]

By the end of the 7th century BC Sparta had become the most powerful city-state in the Peloponnese and was the political and military hegemon over Argos, the next most powerful city-state. Sparta acquired two powerful allies, Corinth and Elis (also city-states), by ridding Corinth of tyranny, and helping Elis secure control of the Olympic Games. Sparta continued to aggressively use a combination of foreign policy and military intervention to gain other allies. Sparta suffered an embarrassing loss to Tegea in a frontier war and eventually offered them a permanent defensive alliance; this was the turning point for Spartan foreign policy. Many other states in the central and provincial northern Peloponnese joined the league, which eventually included all Peloponnesian states except Argos and Achaea. +

The Peloponnesian League was organized with Sparta as the hegemon, and was controlled by the council of allies which was composed of two bodies: the assembly of Spartans and the Congress of Allies. Each allied state had one vote in the Congress, regardless of that state's size or geopolitical power. No tribute was paid except in times of war, when one third of the military of a state could be requested. Only Sparta could call a Congress of the League. All alliances were made with Sparta only, so if they so wished, member states had to form separate alliances with each other. And although each state had one vote, League resolutions were not binding on Sparta. Thus, the Peloponnesian League was not an "alliance" in the strictest sense of the word (nor was it wholly Peloponnesian for the entirety of its existence). The league provided protection and security to its members. It was a conservative alliance which supported Oligarchies and opposed tyrannies and democracies. +

After the Persian Wars the League was expanded into the Hellenic League and included Athens and other states. The Hellenic League was led by Pausanias and, after he was recalled, by Cimon of Athens. Sparta withdrew from the Hellenic League, reforming the Peloponnesian League with its original allies. The Hellenic League then turned into the Athenian-led Delian League. This might have been caused by Sparta and its allies' unease over Athenian efforts to increase their power. The two Leagues eventually came into conflict with each other in the Peloponnesian War. +

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024