Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT GREEK SOCIETY

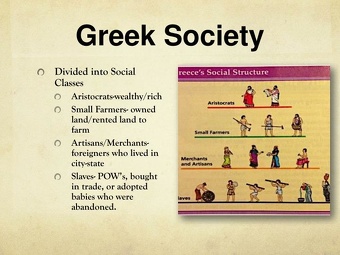

perfume bottle The main groups in ancient Greek society were: 1) male citizens: a) landed aristocrats (aristoi), b) poorer farmers (perioikoi) and c) the middle class (artisans and traders); 2) semi-free labourers (e.g the helots of Sparta); 3) women, of all classes didn’t have citizen rights; 4) children, generally defined as below 18 years; 4) slaves (douloi), who had civil or military duties; and 5)

foreigners: a) non-residents (xenoi) or b) foreign residents (metoikoi) who were below male citizens in status. [Source Mark Cartwright, World History Encyclopedia, May 15, 2018]

Greek aristocrats were not very fond of the masses. One member of the ruling elite used to walk through the streets clubbing people he disliked. Aristotle classified humanity into two kinds of people: The few, smart people destined to be masters: and the multitudes of less talented people designated to be slaves. As people were able to make a living by trading and selling crafts, a fledgling middle class emerged.

Only free, land owning, native-born men could be citizens entitled to the full protection of the law in a city-state. In most city-states, unlike the situation in Rome, social prominence did not allow special rights. Sometimes families controlled public religious functions, but this ordinarily did not give any extra power in the government. In Athens, the population was divided into four social classes based on wealth. People could change classes if they made more money. In Sparta, all male citizens were called homoioi, meaning "peers". However, Spartan kings, who served as the city-state's dual military and religious leaders, came from two families. [Source: Wikipedia]

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Internet Classics Archive " kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People” by Josiah Ober (1989) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Society in Ancient Greece” by Jean-Pierre Vernant and Janet Lloyd (1990) Amazon.com;

“Class in Archaic Greece” by Peter W. Rose (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: From the Archaic Age to the Arab Conquests” by G. E. M. de Ste. Croix (1981) Amazon.com;

“A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture” by Sarah B. Pomeroy, Stanley M. Burstein, et al. (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: History, Culture, and Society” by Ian Morris and Barry B. Powell (2021) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society in Ancient Greece” by M. I. Finley , Brent Shaw, et al. (1982) Amazon.com;

“Technology and Society in the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds” by Tracey Elizabeth Rihll (2013) Amazon.com;

“Greek Civilization and Character; the Self-Revelation of Ancient Greek Society”

by Arnold Toynbee (1964) Amazon.com;

“Pandora's Daughters: The Role and Status of Women in Greek and Roman Antiquity”

by Eva Cantarella, Maureen B Fant, et al. (1987) Amazon.com;

“Voiceless, Invisible, and Countless in Ancient Greece: The Experience of Subordinates, 700—300 BCE” by Samuel D. Gartland and David W. Tandy (2023) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Slavery (Routledge Sourcebook) by Thomas Wiedemann (1980) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in Classical Greece” by N.R.E. Fisher (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way” by Edith Hamilton (1930) Amazon.com;

“The Mask of Apollo” by Mary Renault, (1966), Novel Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1998) Amazon.com;

“Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece” by Robin Waterfield (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“Greek Realities: Life and Thought in Ancient Greece” by Finley P. Hooper (1978) Amazon.com;

Classes in Ancient Greece

Mark Cartwright wrote in the World History Encyclopedia: Although the male citizen had by far the best position in Greek society, there were different classes within this group. Top of the social tree were the 'best people', the aristoi. Possessing more money than everyone else, this class could provide themselves with armour, weapons, and a horse when on military campaign. The aristocrats were often split into powerful family factions or clans who controlled all of the important political positions in the polis. Their wealth came from having property and even more importantly, the best land, i.e.: the most fertile and the closest to the protection offered by the city walls. [Source:Mark Cartwright, World History Encyclopedia, May 15, 2018]

A poorer, second class of citizens existed too. These were men who had land but perhaps less productive plots and situated further from the city, their property was less well-protected than the prime land nearer the city proper. The land might be so far away that the owners had to live on it rather than travel back and forth from the city. These citizens were called the perioikoi (dwellers-round-about) or even worse 'dusty-feet' and they collected together for protection in small village communities, subordinate to the neighbouring city. As city populations grew and inheritances became ever more divided amongst siblings, this secondary class grew significantly.

A third group were the middle, business class. Engaged in manufacturing, trade, and commerce, these were the nouveau riche. However, the aristoi jealously guarded their privileges and political monopoly by ensuring only landowners could rise into positions of real power. However, there was some movement between classes. Some could rise through accumulating wealth and influence, others could go down a class by becoming bankrupt (which could lead to a loss of citizenship or even being enslaved). Ill-health, losing out on an inheritance, political upheavals, or war could also result in the 'best' getting their feet a little dusty.

Women in Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, women had very few rights; they were not citizens and often were not allowed to leave the house. Inside their houses, they were relegated to rooms in the back of the house near the slave quarters. One classics professor told National Geographic: "The Greek polis was something of a men's club. Women tended to stay at home and do the household chores. They went out chiefly for ceremonies, festivals, and such duties as drawing waters. In myth, trysts often took place at wells. Going there was one way a woman got out of the house."

María José Noain wrote in National Geographic History: Life for most women of means centered generally around three stages: kore (young maiden), nymphe (a bride until the birth of her first child), and gyne (woman). Adult life typically began in the early to mid-teens, when she would marry and formally move from her father’s household to her husband’s. Most brides had a dowry that her husband did not have access to, but if the marriage failed, the money would revert to her father. [Source María José Noain, National Geographic History, September 29, 2022]

It is a misconception that women had a universally passive role in Athenian society. Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, It is true that they lived with restrictions modern Westerners would find intolerable. Technically they were not citizens. In terms of civil rights, their status differed little from that of slaves. Marriages were arranged; girls were expected to have children in their midteens. Yet... the assumption that women lived in a state of purdah, completely removed from public life, is contradicted by the depictions of them in art.” Yet, “it would be a mistake to argue that the lot of women there was, after all, a fair deal. The record stands: no citizenship, no vote, little or no control over the use made of your time or your body. But the show is not making that argument. Instead it is using art to survey where, within a system of institutionalized restriction, areas of freedom for women lay.

See Separate Articles: WOMEN IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ; FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT GREECE: WIVES, ROLES, KIDS europe.factsanddetails.com

Slaves in Ancient Greece

collared slaves The Greeks were not known for having a strong work ethic. Citizens abhorred physical labor and came to rely on slaves. Even the tireless classifier himself, Aristotle, believed that the goal of a civilized man was to attain a life of leisure so that he was free to pursue the higher things in life. How was this life of leisure attained?...With slaves, of course. Tradesmen and merchants were looked down upon and teachers and doctors had about the same status as a craftsman. The only respectable occupations were farming, politics and philosophizing. Aristotle also believed that the laws of nature dictated that free men should rule and dominate slaves and women.|[Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

The Greeks used slaves and prisoners to build their temples. Most slaves were people captured in wars or pirates raids. In many cases they were serfs, or conquered people, that came with the land and passed their statuses down from generation to generation .Slaves were bought at the market. The were used in mining, agriculture, construction and as household slaves. Slaves could be craftsmen, entertainers, teachers, secretaries or even businessmen trading for themselves. One thing a slave was not was a citizen. Mycenaean tablets, dated at 1200 B.C., described slave women who worked as grain grinders, spinners, and pourers of baths, They were often grouped by the places they were captured: "women in Asia," "women of Knidoes," "women of Miletos."

Slaves were often freed or allowed to buy their freedom. In many cases, the status of a slave was closer to that of an animal than a human being. They were tortured on the stand in a court of law until they told the "truth" and put to death for simply belonging to a murdered man. They sometimes held their chamber pots of their masters. Slaves were branded on their faces until the A.D. 4th century when Constantine, the first Christianized Roman emperor, decided that it was a inhuman thing to do to a creation of God, so he ordered that they be branded on their arms and legs instead.

See Separate Article: SLAVERY IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Minorities and Racism in Ancient Greece

Different states had different personalities: Sparta was the land of warriors. Sybaris was known for its love of luxury. The word “barbaros”, from which “barbarian” is derived did not originally have pejorative connotations. It simple meant people who didn’t speak Greek and their speech sounded to the Greeks like “bar-bar-bar”.

On racism in ancient Greece and Rome, Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard wrote in her blog A Don’s Life: “There is no doubt at all that they often treated outsiders badly. The idea of the “barbarian” (someone whose speech is just an incomprehensible “ba ba”) is a well known Greek invention. But the cultural identity of both societies was even more pervasively based on what we would now see as an unhealthy distrust of anyone different from themselves. Xenophobia in other words. [Source: Mary Beard, A Don’s Life Blogg, January 22, 2007]

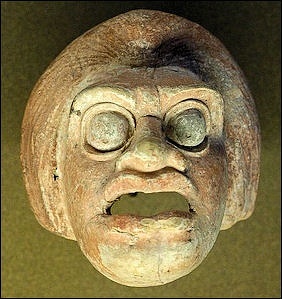

peasant mask

The list of unnatural things that foreigners were supposed to get up to is a long one. It ranged from peculiar eating habits (not just frogs legs or poppadoms, but at its worst cannibalism) to strange regimes of hygiene (women standing up to piss was a notable source of wonderment and/or disdain) and topsy-turvy ideas of sex and gender (women in charge).

The Greeks painted a contemptuous picture of the Persians as trousered, decadent softies who wore far too much perfume. Then the Romans came along and, minus the trousers, said much the same about the Greeks: a nice example of being given a taste of your own medicine. But, strikingly, it’s usually claimed that neither Greeks nor Romans bothered very much about skin colour. This was a time “before colour prejudice”.

It’s certainly the case that there seems to have been no general idea of social, cultural or intellectual inferiority based on the colour of a person’s skin. There was no homogeneous slave class, of a different race and colour from their masters. And, in fact, exactly what skin colours were represented, and in what numbers, in the multi-cultural population of the Roman empire is something of puzzle. The second century AD emperor, Septimius Severus who came from modern Libya definitely wasn’t black (even though that’s sometimes asserted); but then he probably wasn’t as white as some of his marble busts make him seem either.

Ancient stories too suggest a very different set of assumptions about blackness and whiteness. There is marvellous episode which touches just this subject in the Aethiopica (Ethiopian Story), a novel by Heliodorus, a third-century AD Greek writer from Syria. Persinna, the black queen of Ethiopia, with a black husband, gave birth to a white daughter. How did she explain it? She had been looking at a picture of (white) Andromeda at the time of the girl’s conception.

But is it all quite so simple? Probably not. There’s a recent book by Ben Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, which claims to have identified if not racism, then at least “proto-racism” in the ancient world. Isaac insists (as do most serious analysts) that racism goes beyond casual xenophobia. It is a deterministic ideology, which sees some groups as unalterably inferior, thanks to natural or inherited characteristics. In modern society, the key natural characteristic has been skin colour.

Not so in the ancient world. But Isaac thinks he can identify something similarly deterministic (and so racist) in other, quite different, natural factors. For him, the ancients were not colour-prejudiced; instead they were geographical and environmental determinists. To over-simplify a bit, he charges the Greeks and Romans with being “proto-racists” in the sense that they believed that the characteristics which certain races derived from their (inferior) environment and from the climate in which they lived — the rain and fog of Northern Europe, for example — were fixed and irreversibly inferior.

Aristotle on Family and Community Relationships

Aristotle wrote in “Politics,” Book I; Chapter II: “He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin, whether a state or anything else, will obtain the clearest view of them. In the first place there must be a union of those who cannot exist without each other; namely, of male and female, that the race may continue (and this is a union which is formed, not of deliberate purpose, but because, in common with other animals and with plants, mankind have a natural desire to leave behind them an image of themselves), and of natural ruler and subject, that both may be preserved. For that which can foresee by the exercise of mind is by nature intended to be lord and master, and that which can with its body give effect to such foresight is a subject, and by nature a slave; hence master and slave have the same interest. Now nature has distinguished between the female and the slave. For she is not niggardly, like the smith who fashions the Delphian knife for many uses; she makes each thing for a single use, and every instrument is best made when intended for one and not for many uses. But among barbarians no distinction is made between women and slaves, because there is no natural ruler among them: they are a community of slaves, male and female. Wherefore the poets say, "It is meet that Hellenes should rule over barbarians; "as if they thought that the barbarian and the slave were by nature one. [Source: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

Spartan woman gives a shield to her son

“Out of these two relationships between man and woman, master and slave, the first thing to arise is the family, and Hesiod is right when he says, "First house and wife and an ox for the plough, " for the ox is the poor man's slave. The family is the association established by nature for the supply of men's everyday wants, and the members of it are called by Charondas 'companions of the cupboard,' and by Epimenides the Cretan, 'companions of the manger.' But when several families are united, and the association aims at something more than the supply of daily needs, the first society to be formed is the village. And the most natural form of the village appears to be that of a colony from the family, composed of the children and grandchildren, who are said to be suckled 'with the same milk.' And this is the reason why Hellenic states were originally governed by kings; because the Hellenes were under royal rule before they came together, as the barbarians still are. Every family is ruled by the eldest, and therefore in the colonies of the family the kingly form of government prevailed because they were of the same blood. As Homer says: "Each one gives law to his children and to his wives. " For they lived dispersedly, as was the manner in ancient times. Wherefore men say that the Gods have a king, because they themselves either are or were in ancient times under the rule of a king. For they imagine, not only the forms of the Gods, but their ways of life to be like their own.

“When several villages are united in a single complete community, large enough to be nearly or quite self-sufficing, the state comes into existence, originating in the bare needs of life, and continuing in existence for the sake of a good life. And therefore, if the earlier forms of society are natural, so is the state, for it is the end of them, and the nature of a thing is its end. For what each thing is when fully developed, we call its nature, whether we are speaking of a man, a horse, or a family. Besides, the final cause and end of a thing is the best, and to be self-sufficing is the end and the best.

“Hence it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal. And he who by nature and not by mere accident is without a state, is either a bad man or above humanity; he is like the "Tribeless, lawless, hearthless one, " “whom Homer denounces- the natural outcast is forthwith a lover of war; he may be compared to an isolated piece at draughts.

“Now, that man is more of a political animal than bees or any other gregarious animals is evident. Nature, as we often say, makes nothing in vain, and man is the only animal whom she has endowed with the gift of speech. And whereas mere voice is but an indication of pleasure or pain, and is therefore found in other animals (for their nature attains to the perception of pleasure and pain and the intimation of them to one another, and no further), the power of speech is intended to set forth the expedient and inexpedient, and therefore likewise the just and the unjust. And it is a characteristic of man that he alone has any sense of good and evil, of just and unjust, and the like, and the association of living beings who have this sense makes a family and a state.

“Further, the state is by nature clearly prior to the family and to the individual, since the whole is of necessity prior to the part; for example, if the whole body be destroyed, there will be no foot or hand, except in an equivocal sense, as we might speak of a stone hand; for when destroyed the hand will be no better than that. But things are defined by their working and power; and we ought not to say that they are the same when they no longer have their proper quality, but only that they have the same name. The proof that the state is a creation of nature and prior to the individual is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole. But he who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state. A social instinct is implanted in all men by nature, and yet he who first founded the state was the greatest of benefactors. For man, when perfected, is the best of animals, but, when separated from law and justice, he is the worst of all; since armed injustice is the more dangerous, and he is equipped at birth with arms, meant to be used by intelligence and virtue, which he may use for the worst ends. Wherefore, if he have not virtue, he is the most unholy and the most savage of animals, and the most full of lust and gluttony. But justice is the bond of men in states, for the administration of justice, which is the determination of what is just, is the principle of order in political society. . . .

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024