Home | Category: Alexander the Great

MACEDONIA

Macedonia, also called Macedon, was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal Argead dynasty, which was followed by the Antipatrid and Antigonid dynasties. Alexander the Great and his father Philip II are the most famous Macedonians. [Source Wikipedia]

The geographical and historical region of Macedonia lies of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. Its borders have changed considerably over time. Today the region is considered to include parts of six Balkan countries 1) all of North Macedonia, large parts of Greece and Bulgaria, and smaller parts of Albania, Serbia, and Kosovo. It covers approximately 67,000 square kilometers (25,869 square miles. Greek Macedonia comprises about half of Macedonia's area,

Macedonia is very mountainous. What is now northern Greece is very mountainous and rugged. The country of North Macedonia is landlocked country and geographically clearly defined by a central valley formed by the Vardar river and framed along its borders by mountain ranges. The Šar Mountains and Osogovo frame the valley of the Vardar river.

See Separate Article: PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER): HIS LIFE, LOVES, MURDER, AND RISE OF MACEDON europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Unearthing the Family of Alexander the Great: The Remarkable Discovery of the Royal Tombs of Macedon” by David Grant (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Macedonia” by Carol J. King (2017) Amazon.com;

“Macedonia from Philip II to the Roman Conquest” by René Ginouvès. Iannis Akamatis. David Hardy (1994) Amazon.com;

“Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism” (2014) Amazon.com;

“Macedonia: A History” by Simon Tasievski, Krste Misirkov, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Women and Monarchy in Macedonia” by Carney (2021) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Macedonia (Blackwell Companions) by Joseph Roisman and Ian Worthington (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Macedonia” by Miltiades B. Hatzopoulos (2020) Amazon.com;

“Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History” by Andrew Rossos (Hoover Institution Press Publication) (2008) Amazon.com;

“King and Court in Ancient Macedonia: Rivalry, Treason and Conspiracy”by Elizabeth Carney (2015) Amazon.com;

“Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Courts of Philip II and Alexander the Great: Monarchy and Power in Ancient Macedonia” by Frances Pownall, Sulochana R. Asirvatham, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Macedonian War Machine, 359–281 BC: Neglected Aspects of the Armies of Philip, Alexander and the Successors (359-281 BC)” by David Karunanithy (2020) Amazon.com;

“Hellenica” by Xenophon (Landmark) Amazon.com;

“Roman Conquests: Macedonia and Greece” by Philip Matyszak (Author) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Alexander” by Mary Renault (1975) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Robin Lane Fox (1973) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life” by Thomas R. Martin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

History of Macedonia

The oldest known settlements in Macedonia date back approximately to 7,000 B.C. Graves with ornamental burial goods dating to 3,000 years ago have been found at Aigai, which became a significant-size settlement around the seventh century B.C. At that time the Temenids, a Macedonian royal dynasty that claimed direct descent from Zeus and Hercules, established their capital there. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “According to legend, the first Temenid king, Perdiccas, was told by the oracle at Delphi that a herd of white goats would lead him to the site of his kingdom’s capital. Perdiccas followed the goats to the foothills of the Pierian Mountains, overlooking the Haliacmon River as it crosses the wide green Macedonian plain. “The word aigai means ‘goats’ in ancient Greek,” says Angeliki Kottaridi, director of the Imathia Ephorate of Antiquities and the main archaeologist at Aigai,

“The culture of the ancient Macedonian people, who originated as herding and hunting tribes north of Mount Olympus, became more Greek under Temenid rule. They spoke a dialect of the Greek language and worshiped Greek gods. “One of the important discoveries at Aigai was the tombstone carvings,” says Kottaridi. “They taught us that everyone here had Greek names. They thought of themselves as Macedonians and Greeks.”

In the eyes of sophisticated Athenians, however, they were northern barbarians who mangled the language, practiced polygamy, guzzled their wine without diluting it, and were more likely to brawl at the symposium than to discuss the finer points of art and philosophy. The Athenian politician Demosthenes once described Philip II as “a miserable Macedonian, from a land from which previously you could not even buy a decent slave.”

Aigai (Vergina) — Ancient Capital of Macedon

Philip II's tomb in Vergina

Aigai (near present-day Vergina) was an important city in Macedonia during the time of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. Although the Macedonians had moved their capital to Pella, about 50 kilometers (30 miles northeast), by the time Alexander was born, Aigai remained the center of political and religious life. It’s where Philip II of Macedon was famously assassinated in 336 B.C. Alexander was hastily crowned in the palace afterward, and Philip was buried nearby. [Source: Julia Buckley, National Geographic, January 4, 2024]

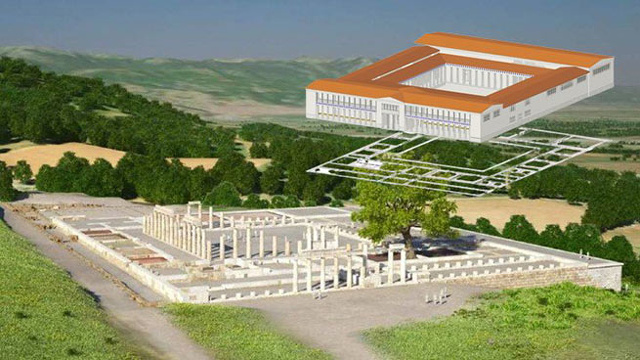

The Archaeological Site of Aigai (modern name Vergina) was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. It is where Philip II of Macedon built his monumental palace in the fourth century B.C. after ed nearly all of classical Greece. According to UNESCO: “The city of Aigai, the ancient first capital of the Kingdom of Macedonia, was discovered in the 19th century near Vergina, in northern Greece. The most important remains are the monumental palace, lavishly decorated with mosaics and painted stuccoes, and the burial ground with more than 300 tumuli, some of which date from the 11th century B.C. One of the royal tombs in the Great Tumulus is identified as that of Philip II, who conquered all the Greek cities, paving the way for his son Alexander and the expansion of the Hellenistic world.[Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The city of Aigai is located between the modern villages of Palatitsia and Vergina, in Northern Greece (Region of Hemathia). At Aigai was rooted the royal dynasty of the Temenids, the family of Philip II and Alexander the Great. The Archaeological Site of Aigai, containing an urban center – the oldest and most important in Northern Greece – and several surrounded settlements, is defined by the rivers Haliakmon (W and N), Askordos (E), and the Pierian Mountains (S). Aigai provides important information about the culture, history and society of the ancient Macedonians, the Greek border tribe that preserved age-old traditions and carried Greek culture to the outer limits of the ancient world. The most important, already excavated, archaeological remains of the site are: the monumental palace (ca 340 B.C.), which was the biggest and one of the most impressive buildings of classical Greece, the theatre, the sanctuaries of Eukleia and the Mother of the Gods, the city walls, the royal necropolis, containing more than 500 tumuli, dating from the 11th to 2nd century B.C. . Three royal burial clusters have been already excavated. Twelve monumental temple-shaped tombs are known. Among them is the tomb of Euridice, mother of Philip II and the unlooted tombs of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great, and his grandson, Alexander IV, which have been discovered in 1977-8 and made a worldwide sensation. The quality of the tombs themselves and their grave-goods places Aigai among the most important archaeological sites in Europe. =

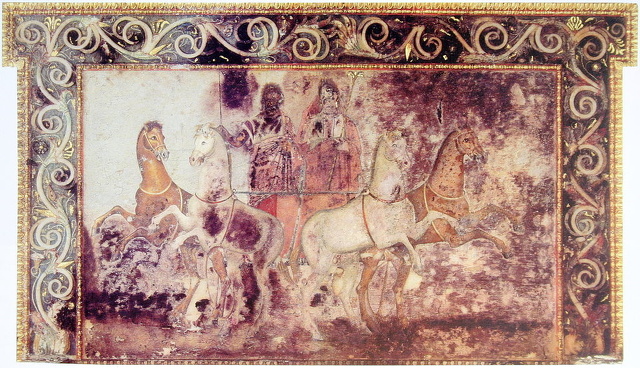

“The site represents an exceptional testimony to a significant development in European civilization, at the transition from the classical city state to the imperial structure of the Hellenistic and Roman periods. This is vividly demonstrated in particular by the remarkable series of royal tombs and their rich contents. Both the cemetery and the city contain original and unique historical, artistic and aesthetic achievements of the late classical art of extraordinarily high quality and historical importance, such as the architectural form of the royal palace and the magnificent wall paintings of the so-called Macedonian tombs, as well as objects such as the ivory portrait and miniature art, metal, gold and silver work. Many of these achievements were created by great artists of ancient Greece, such as Leochares and Nikomachos. =

“The subterranean temple-shaped tombs are amongst the best-preserved examples on the use of colour in ancient architecture, and their discovery revealed for the first time the intact façade of an ancient Greek building. The complete and emblematic form of the royal palace, based on philosophical, political and architectural notions (archetype of peristyle palatial buildings), served in antiquity and modern times as the prototype and a visual statement of the notion of the enlightened kingship. Some of the royal tombs have been sheltered. The protection of the monuments and their natural environment as a unit ensures the authentic context of the city and its cemeteries. =

Archaeological Work at Aigai

Archaeologist Angeliki Kottaridi is the director of operations at Aigai. Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: At Aigai, it is Philip who looms largest among the ruins, even though the place was vitally important for Alexander too. Excavations have revealed that Philip transformed the ancient city, revolutionized its political culture, and turned it into a symbol of power and ambition. [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

The remains of the outdoor theater that Philip built near his palace is where he entertained dignitaries from across Greece and the Balkans, and where he ultimately met his death in a shocking public assassination. Kottaridi and her colleagues have found graves and ornamental burial goods dating back perhaps 3,000 years. At Lefkadia, 20 miles from Aigai, the Tomb of Judgment pays tribute to Macedonian valor. The great painted facade incorporates images of a warrior con- ducted into the underworld by the god Hermes.

Philip II of Macedonia

“After the breakup of the Macedonian kingdom by the Romans in the second century B.C., Aigai fell into decline and obscurity. Then, in the first century A.D., a massive landslide buried the city and consigned it to oblivion, although a large burial mound remained clearly visible at the edge of the plain called the Great Tumulus. “Itt was a very ugly excavation,” Kottaridi says. “Just earth, earth, earth. Nothing but earth for 40 days. Then the miracle.” Excavating 16 feet down with a small hoe, Andronikos uncovered two royal tombs and dated them to the fourth century B.C. Other royal tombs discovered nearby had been looted in antiquity. But these newly unearthed ones were sealed and intact. That night, with guards posted at the dig, the two researchers barely slept.

“The following day, they pried open the marble door to the first tomb. They stepped into a large, vaulted, double chamber strewn with smashed pottery, silver vases, bronze vessels, armor and weapons, including a golden breastplate and a beautiful gilded arrow quiver. Painted on one wall was a breathtaking frieze depicting Philip II and a young Alexander, both on horseback, hunting lions and other animals.

A massive new museum at Aigai opened in December 2022. It displays more than 6,000 items, spanning 13 centuries, found at the site. A staff of 75 worked on a $22 million partial restoration of Philip II’s palace — the largest building in classical Greece, three times the size of the Parthenon in Athens.

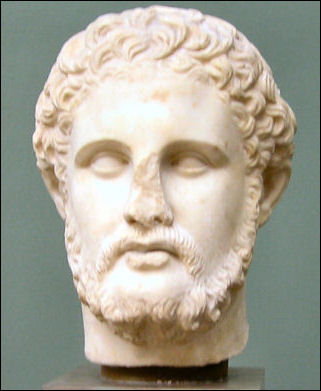

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.), Alexander the Great's father, was the King of Macedonia and Olympias. He became king of Macedon in 359 B.C. at about the age of 23 and ruled for 23 years. An adept warrior, strategist and warrior, he transformed Macedonia from a loose confederation of tribes and cities into a powerful kingdom and introduced an agile cavalry and long pikes to warfare as he overhauled his army.

Philip II was blinded by an enemy's arrow and was lamed in a battle. He enjoyed wine, lavish feasts and women. He had at least seven wives. Like many upper class Greek men, Philip was also reportedly a bisexual. He showed great courage in battle, was a shrewd politician and patronized the arts, filling his court with writers, artists, philosophers and actors.

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Philip II of Macedon took a faction-rent, semi-civilized country of quarrelsome landed nobles and boorish peasants, and made it into an invincible military power. The conquests of Alexander the Great would have been impossible without the military power bequeathed him by his almost equally great father. At the very outset of his reign Philip had to confront sore perils in his own family and among the vassals of his decidedly primitive kingdom.”

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the first half of the fourth century B.C., Greek poleis, or city-states, remained autonomous. As each polis tended to its own interests, frequent disputes and temporary alliances between rival factions resulted. In 360 B.C., an extraordinary individual, Philip II of Macedonia (northern Greece), came to power. In less than a decade, he had defeated most of Macedonia's neighboring enemies: the Illyrians and the Paionians to the west and northwest, and the Thracians to the north and northeast. Philip II instituted far-reaching reforms at home and abroad. Innovations—improved catapults and siege machinery, as well as a new kind of infantry in which each soldier was equipped with an enormous pike known as a sarissa—placed his armies at the forefront of military technology. In 338 B.C., at the pivotal battle of Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II completed what was to be the last phase of his domination when he became the undisputed ruler of Greece. His plans for war against Asia were cut short when he was assassinated in 336 B.C. Excavations of the royal tombs at Vergina in northern Greece give a glimpse of the vibrant wall paintings and rich decorative arts produced for the Macedonian royal court, which had become the leading center of Greek culture.” [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

Rulers of Macedonia (496–168 B.C.)

Alexander I coin

Alexander I (496–454 B.C.)

Perdikkas II (454–413 B.C.)

Archelaos I (413–399 B.C.)

Aeropos II (398–395 B.C.)

Amyntas II (395–394 B.C.)

Amyntas III (393–370 B.C.)

Perdiccas III (365–359 B.C.)

Philip II (360/59–336 B.C.)

Alexander III (the Great) (336–323 B.C.)

Philip III Arrhidaios (323–317 B.C.)

Alexander IV (323–310 B.C.)

Philip II coin

Olympias Alexander the Great's mother (317–316 B.C.)

Cassander (315–297 B.C.)

Philip IV (297 B.C.)

Antipatros and Alexander V (297–294 B.C.)

Demetrios I Poliorketes ("Besieger") (294–288 B.C.)

Pyrrhos of Epeiros (288/7–285 B.C.)

Lysimachos (288/7–281 B.C.)

Seleukus (281 B.C.)

Ptolemaios Keraunos ("Thunderbolt") (281–279 B.C.)

Antigonos II Gonatas (ca. (277–239 B.C.)

Demetrios II (239–229 B.C.)

Antigonos III Doson (ca. (229–222 B.C.)

Philip V (222–179 B.C.)

Perseus (179–168 B.C.)

Tomb of Philip II

In November 1977, Dr. Manolis Andronicos, an archaeologist at the University of Thessalonika unearthed a tomb under a mound in Vergina (40 kilometers west of Thessalonika, Greece) that is believe belonged to Philip II or Philip III. [Source: Manolis Andronicos, National Geographic, July 1978]

No inscription or definitive proof was found that linked the tomb to Philip II. Evidence that kinked the tomb to him included the discovery in the tomb of an ivory head thought to be a likeness of Philip and a diadem associated with Macedonian royalty, different size leg armor (possibly an accommodation to Philip II's bad leg), the high value of the objects and the dating of the objects to the time of Philip II reign. Evidence that refutes the claim are tooth remains usually associated with a man in his 30s (Philip II was 46 when he died).

The tomb was very deep (23 feet under the ground), presumably to foil grave robbers. It was a barrel- vaulted structure with extraordinary Greek wall paintings with images of Pluto, god of the Underworld , abducting Persephone and a hunting scene with five horsemen with dogs and three hunters with spears pursuing wild boar and lions. These images unfortunately faded after they were exposed to sunlight and air.

Among the he objects found in the tomb were a marble sarcophagus, a large golden casket, a gold larnax (small casket) with a Macedonian star that contained cremated remains, a royal wreath of golden acorns and oak leaves, a gold-and-silver diadem, a golden quiver, purple fabric thread with gold, a perforated bronze lantern, weapons, silver vessels, bronze vessels, bronze armor, an iron helmet, a sword, scepter, sandals, a shield," spear points, javelins, golden lion heads, and sculpture, possibly of Alexander the Great.

The Vergina tomb was actually comprised of two tombs. Tomb I, which held human remains but had been looted in antiquity; and Tomb II, which was filled with treasure and armor, as well as the burnt bones of a man and a woman. Tomb II was identified as the final resting place of Philip II. But that identification is hotly contested. Some archaeologists believe that the bones actually belong to Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother and a short-lived figurehead king. Philip II, they say, may actually rest in the looted Tomb I. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2015 ]

About 450 tombs dating to the 6th century B.C. have been found at a site called Archontiko in the Macedonian part of northern Greece. Archaeologists Pavlos and Anastasia Chrysostomou, of the Greek Ministry of Culture, say they have found scores of warriors buried with armor, swords, shields adorned with gold and silver as well as noble women with gold, silver amber and faience. These give clues to the rich warrior culture was thriving two centuries before Alexander's birth.

New Tomb for Philp II?

Philip II may be buried in a different tomb than was previously thought; Tomb 1 rather than Tomb II at Vergina. Sindya N. Bhanoo of the New York Times wrote: “A new study relying on the scanning and radiography of skeletal remains suggests that of the three tombs found on the Great Tumulus hill in the northern Greek town of Vergina, the king is likely to be buried in what is known as Tomb 1, not Tomb 2. The study appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Source: Sindya N. Bhanoo, New York Times, July 20, 2015]

“Philip II sustained a lance-inflicted leg wound three years before he was slain in 336 BCE. Tomb 1 contains an approximately 45-year-old individual with a hole near the knee, suggesting a piercing wound accompanied by inflammation and bone fusion.” Tomb 1 also contains the leg bones of an 18-year-old female and infant; these are thought to be the king’s wife and their child, both slain shortly after his death.”

Some argue that the leg bones belong to Philip II's wife Cleopatra. According to Livescience she was a robust woman who stood about 5 feet 4 inches (165 centimeters), according to the measurement of these bones. Tiny newborn bones found in Tomb I belong to a child only one to three weeks past its due date. (It is impossible to know the baby's exact age, as it isn't clear from bones alone when an infant was born.) Anthropologists aren't sure of this infant's sex, but it may have been the murdered newborn child of Philip II and his seventh wife Cleopatra. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2015 ]

Philip III Arrhidaios — Alexander the Great's half-brother and successor — and his young warrior-queen wife Eurydice, were respectively killed and forced to commit suicide by Olympias, Philip III's stepmother and Alexander’s mother. Historical texts say that Philip II was buried, exhumed, burned and re-buried: A royal tomb found in Greece containing the burned bones of a man and a young woman, some scholar believe, could belong to Philip III and Eurydice. Others say the entombed man is probably Philip II, Alexander the Great's father, making the woman in the tomb Cleopatra, Philip II's last wife (She is different from the famous Cleopatra). This Cleopatra also met a tragic end. She was either killed or forced to commit suicide by Olympias. Scholars are still debating issues whether the bones were burned dry or covered in flesh and viscera. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, April 8, 2011]

Which Tomb is Philip II Buried In?

larnax from Philip II's tomb

In the early 2020s, researchers used X-ray analyses and carefully examined historical record to determine the occupants inside a the three of royal tombs in Greece said to contain Philp II. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: To determine the identities of the skeletons, the archaeologists behind a new review looked at ancient writings about each individual, including any injuries or skeletal anomalies that could help identify them, and compared these to X-rays of each skeleton. "It was like a fascinating detective's ancient story," review lead author Antonios Bartsiokas, professor emeritus of anthropology and paleoanthropology at the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece, told Live Science. [Source Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, February 14, 2024]

Bartsiokas and colleagues identified King Philip II as the occupant of Tomb I based on the male skeleton's fused knee joint. The injury was "consistent with the historic evidence of the lameness of King Philip II," according to the review. He was buried alongside one of his wives, Queen Cleopatra, and their newborn child, the researchers suggested. "This was the only newborn in the Macedonian dynasty to have died shortly after it was born," Bartsiokas said. "The age of the female skeleton at 18 years old was determined based on the epiphyseal lines [which show when the bone stopped growing] of her humerus. [This number] coincides with the age of Cleopatra from the ancient sources."

However, experts have long argued that King Philip II was actually buried in Tomb II, and not in Tomb I as the review concluded. Because no physical trauma was found on the male skeleton in Tomb II, the new review concluded that he was King Philip III Arrhidaeus, He was buried with his wife, Adea Eurydice, a "warrior woman who was leader of the army," Bartsiokas said. Her skeleton was surrounded by several pieces of weaponry, according to the review.

"His skeletal evidence and the pattern of his cremated bones have been shown to be consistent with the circumstances of the death of King Arrhidaeus and his wife," Bartsiokas said. "Tomb I was a very small and poor tomb and Tomb II was very big and rich. This ties with the historical evidence that Macedonia was in a state of bankruptcy when Alexander started his campaign and very rich when he died. This is consistent with Tomb I belonging to Philip II and Tomb II belonging to his son Arrhidaeus."

Moreover, the skeleton in Tomb II didn't have a tell-tale sign that has been associated with Philip II: an eye injury. Previous studies determined that the male skull in Tomb II showed a traumatic injury on the right side of the skull, but those claims have been refuted in several studies, including in this new review. "Philip II is known from ancient sources to have suffered an eye injury that blinded him," Bartsiokas said. "I was surprised to find [the] absence of such an eye injury in the male skeleton of Tomb II, which was initially widely described as a real injury that identified Philip II. In other words, this was a case of a description of a morphologic feature that did not exist." This detail also helped the researchers determine that Tomb II didn’t house Philip II’s remains. Of note, the part of the skull that would have held the eye injury in Tomb I was not preserved. Lastly, researchers identified the occupant of Tomb III as Alexander IV, Alexander the Great's teenage son who was killed in a power struggle following his father's death — a conclusion that "most scholars agree" upon, the authors wrote in the review.

Ian Worthington, a professor of ancient history at Macquarie University in Sydney who was not involved in the review, told Live Science that the "fascinating" review contained "rich analysis of forensic examinations and some historical context and mention of opposing views," but that he still thinks Philip II was buried in Tomb II. Among other things, crucially, is that the two chambers of Tomb II were built at different times, whereas the burial of Philip III and Eurydice was a planned double one, meaning the construction of both tombs should be contemporaneous," Worthington said.

Worthington also concluded that there is evidence of eye trauma in the skull fragments. "There is also the significant issue of the trauma around the right eye of the skull from Tomb II, which is consistent with the wound that Philip suffered at Methone in 354 [B.C.] when a bolt from the ramparts struck him in the eye," Worthington said. "Even the undecorated walls of the tomb (in contrast to Tomb I) lean toward Philip II being the occupant, as we know that his son and successor Alexander III [had] to bury his father quickly to deal with a revolt of the Greeks and conduct a purge against opponents. Alexander planned to revisit the tomb and make it one to rival the pyramids, but he never did."

Bartsiokas, however, disagreed, saying that while Tomb II has undecorated walls, it has an elaborate facade on its front wall, an impressive antechamber and dual cremated burials, all of which would have taken a while to complete and making it a good candidate for being the tomb for Alexander's half-brother and sister-in-law. He also took issue with the idea that Tomb II had chambers built at different times, as previous research showed that "the remnants of the pyre were found on the roof of both chambers of Tomb II," he told Live Sciencel. Worthington added that while we will likely not know for sure who the occupants are, Philip II is the most likely candidate. "Ultimately, no identification of the deceased in Tomb II can ever be 100 percent compelling in light of present evidence, analysis and reasoned historical argument, but on balance, the tomb is most likely that of Macedonia's greatest king, Philip II."

Philippi; The City Founded by Philip

According to UNESCO: “The remains of this walled city lie at the foot of an acropolis in north-eastern Greece, on the ancient route linking Europe and Asia, the Via Egnatia. Re-founded in 356 B.C. by the Macedonian King Philip II, the city developed as a “small Rome” with the establishment of the Roman Empire in the decades following the Battle of Philippi, in 42 B.C.. The vibrant Hellenistic city of Philip II, of which the walls and their gates, the theatre and the funerary heroon (temple) are to be seen, was supplemented with Roman public buildings such as the Forum and a monumental terrace with temples to its north. Later the city became a centre of the Christian faith following the visit of the Apostle Paul in 49-50 CE. The remains of its basilicas constitute an exceptional testimony to the early establishment of Christianity. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The walled city was subject to major destruction in the earthquake of 620 CE. Many stones and elements of the buildings including inscriptions and mosaic and opus sectile floors remain in situ from that time, although some stones were subsequently reused in later buildings. Modern constructions and interventions at the site have been generally limited to archaeological investigations and necessary measures for the protection and enhancement of the site. For the most part the principle of reversibility has been respected and the walled city can be considered authentic in terms of form and design, location and setting. =

Philip II’s Palace

Philip’s vast royal complex, covering an area of nearly four acres, is the largest ancient Greek monument. It is larger than any monument in Athens. Philip’s stone and tile-roofed palace has a shrine to Hercules, a series of lavish banquet halls and an inner courtyard built to seat 8,000. The two-storied colonnade was the first known in Greek architecture.

Richard Grant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The peristyle, or main courtyard, is 130,000 square feet. “This was a political building, not a home, and it was open to the public,” she says. “It was a place for feasts, political meetings, philosophical discussions, with banqueting rooms on the second floor and a library. The peristyle was flanked by stone colonnades, which we are restoring to a height of six meters. We are redoing all the mosaics on the floor. It is very difficult to find stonemasons and mosaic-makers who can do this work by hand.” [Source: Richard Grant, Smithsonian magazine, June 2020]

The great palace, “utterly revolutionary and avant-garde for its time,” Kottaridi says, was two stories high and visible from the entire Macedonian basin. It was a symbol of Philip’s power and sophistication, a reflection of his ambition, and a retort to the Athenians who had derided him and were now his subjects.

The Palace of Aigai was finished by Phillip II in 336 B.C., the same year Alexander the Great was proclaimed king of Macedonia at the palace. Columns line the walkways and form a square-shaped courtyard. Around the outside of the courtyard are intricate mosaic floors. The Palace of Aigai was destroyed in the second century B.C. after the ancient Romans conquered the Greeks, officials said in the release. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, January 9, 2024]

Archaeologists began restoration work on the Palace of Aigai in 2007. The 16-year-long restoration project involved excavating the ruins, preserving the findings and piecing back together any surviving fragments. Missing sections were replicated and replaced. In total, the project cost about $22.3 million and was partially financed by the European Union. The full site was opened to the public in January 2024 Vergina is about 490 kilometers (300 miles) northwest of Athens.

New Museum at Aigai

The Polycentric Museum of Aigai (an hour’s drive west of Thessaloníki) opened in late 2022. Julia Buckley wrote in National Geographic: Visitors can walk between the tombs in the darkness and marvel at the door of Philip’s grave — adorned with a 2,360-year-old fresco depicting the king and Alexander hunting. Nearby, burial artifacts are on display, including ivory couches, rich textiles that once wrapped bones, and delicate golden wreaths and ossuaries. There’s even a set of Philip’s gleaming armor.[Source: Julia Buckley, National Geographic, January 4, 2024]

The sites of Aigai are overseen Kottaridi. She always wanted to tell the story of the commoners of the city, too. The new Central Museum Building does just that, transforming the remains of Aigai into a vast, “scattered” (or polycentric) site. In contrast to the low-lit Royal Tombs, the new showplace is made of gleaming white stone and flooded with natural light. “I wanted this to have a different concept,” says Kottaridi, explaining the distinction between the two museums. “White is the light from beyond — so this is a place from beyond, where [the dead] can share their stories.”

The new museum begins in an atrium displaying part of the columned peristyle of Aigai’s Royal Palace — a vast building whose double colonnade, Kottaridi says, inspired architecture from Athens to Asia — and then shows sculptures from the ancient city, including a formidable, stern-faced statue of Eurydice, Alexander’s grandmother. The museum’s main hall further illustrates the lives of ordinary citizens by displaying very ordinary things — lamps, keys, pots, figurines, and simple iron nails — in backlit cases, like works of art. “For the first time, there’s no taboo about exhibiting ‘worthless’ items,” says tour guide Athina Tsakiri, who has been bringing visitors to the site since it opened. “This is cheap stuff that usually nobody pays attention to.” “In other museums, you have just masterpieces; here we have normal things, the reality of life,” adds Kottaridi.

One case contains nothing but terracotta tile shards — clearly disturbed while wet — with a human handprint and the claw and paw prints of dogs, cats, and roosters. Another area showcases the domestic lives of women, with cases of jewelry, hairpins, makeup pots, and a loom reconstructed on a plastic frame, slung with dozens of terracotta weights. A case of hand-turned iron keys stands as evidence of past lives. “The houses aren’t with us, but the key is the idea of the house,” says Kottaridi.

The final gallery of the small museum showcases relics from cremations of Philip and Alexander’s ancestors from 580-300 B.C. Back then, royals (initially, only the men) were cremated on funeral pyres with house-like structures built on top of them. Potshards, nails, and even half-melted door-knockers are all piled together, left as they would have been after a cremation. Jewelry placed on the bodies of nine Macedonian queens has been reconstructed in life-size cases, including that of the fifth-century-B.C. “Lady of Aigai,” whose body, dressed in gold, was excavated by Kottaridi in 1988.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024