Home | Category: Alexander the Great / Alexander the Great's Conquests / After Alexander the Great

DEATH OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT

Dying Alexander receiving his soldiers

Alexander died just short of his 33 birthday on June 10, 323 B.C. The cause of his death is unknown. In some accounts he drank a huge amount of wine at a banquet and collapsed with a fever. In other accounts he became sick, perhaps with malaria, on his way back from India. Most scholars believe that was a major factor in his death. In Susa a fakir brought from India had prophesied Alexander's death.

In early 323 B.C., Alexander entered Babylon to prepare for an Arabian expedition. At a banquet he was seized with abdominal pains and was forced to retire to his quarters. He then came down with a fever and soon was so ill he couldn't speak or move. Twelve days later before he died.

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “The circumstances of his death are almost as unclear as those of his father, though it probably smacks too much of the historical novel to suggest that Alexander was assassinated, possibly by poison. Rather, he is most likely to have caught a deadly fever, probably malarial, after years of pushing himself beyond reasonable limits.” [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Alexander's symptoms included a fever, thirst, abdominal pain and paralysis. His symptoms match up well with West Nile virus encephalitis. There were stories that birds dropped dead at his feet when he entered Babylon. West Nile virus encephalitis was not identified until 1937 but is thought to have been around much longer than that. some scholars believe he may have had typhoid-induced ascending paralysis which also makes one look dead before they actually die.

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ; SELEUCIDS AND THE DIVISION OF ALEXANDER’S EMPIRE AFTER HIS DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

"Dividing the Spoils: 'The War for Alexander the Great's Empire" by Robin Waterfield (Oxford University Press, 2011); Amazon.com;

“Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the Bloody Fight for His Empire” by James S. Romm (2011) Amazon.com;

“After Alexander: The Time of the Diadochi (323-281 BC)” by Victor Alonso Troncoso, Edward M. Anson Amazon.com;

“Alexander’s Veterans and the Early Wars of the Successors” by Joseph Roisman (2012) Amazon.com;

“Funeral Games” by Mary Renault (1981), novel about after Alexander the Great’s death Amazon.com;

“The Quest for the Tomb of Alexander the Great”

by Andrew Chugg (2012) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: From His Death to the Present Day” by John Boardman (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Death of Alexander the Great: What-or Who-Really Killed the Young Conqueror of the Known World?” by Paul Doherty (2009) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Death of a God” by Paul Doherty (2013) Amazon.com;

“Olympias: Mother of Alexander the Great” by Elizabeth D. Carney (2006) Amazon.com;

“Macedonia from Philip II to the Roman Conquest” by René Ginouvès. Iannis Akamatis. David Hardy (1994) Amazon.com;

“King and Court in Ancient Macedonia: Rivalry, Treason and Conspiracy”by Elizabeth Carney (2015) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Alexander” by Mary Renault (1975) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Robin Lane Fox (1973) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life” by Thomas R. Martin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Primary Sources:(Also available for free at MIT Classics, Gutenberg.org and other Internet sources):

“History of Alexander” by Quintus Curtius Rufus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica” by Arrian (Oxford World Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander” by Arrian Amazon.com;

“The Life of Alexander the Great” by Plutarch (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

Eulogy of Alexander

Arrian wrote: “Whoever therefore reproaches Alexander as a bad man, let him do so; but let him first not only bring before his mind all his actions deserving reproach, but also gather into one view all his deeds of every kind. Then, indeed, let him reflect who he is himself, and what kind of fortune he has experienced; and then consider who that man was whom he reproaches as bad, and to what a height of human success he attained, becoming without any dispute king of both continents, and reaching every place by his fame; while he himself who reproaches him is of smaller account, spending his labour on petty objects, which, however, he does not succeed in effecting, petty as they are. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

“For my own part, I think there was at that time no race of men, no city, nor even a single individual to whom Alexander’s name and fame had not penetrated. For this reason it seems to me that a hero totally unlike any other human being could not have been born without the agency of the deity. And this is said to have been revealed after Alexander’s death by the oracular responses, by the visions which presented themselves to various people, and by the dreams which were seen by different individuals. It is also shown by the honour paid to him by men up to the present time, and by the recollection which is still held of him as more than human. Even at the present time, after so long an interval, other oracular responses in his honour have been received by the nation of the Macedonians. In relating the history of Alexander’s achievements, there are some things which I have been compelled to censure; but I am not ashamed to admire Alexander himself. Those actions I have branded as bad, both from a regard to my own veracity, and at the same time for the benefit of mankind. For this reason I think that I undertook the task of writing this history not without the divine inspiration.”

Tomb of Alexander the Great

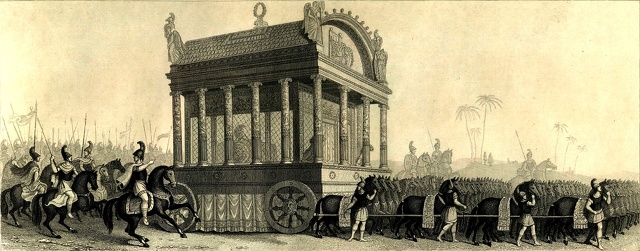

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: “When St. John Chrysostom visited Alexandria in A.D. 400, he asked to see Alexander’s burial place, adding, “His tomb even his own people know not.” It is a question that continues to be asked now. For two years, Alexander’s mummified remains, housed in a golden sarcophagus, lay in state, a pawn in the game of royal succession. Finally, it was decided that Alexander would be buried in Greece at Aegae, the first capital of the Macedonian kings. But according to ancient sources, his hearse was hijacked near Damascus and the corpse taken to Egypt, first to Memphis, and, some time between 298 and 283 B.C., to Alexandria, the city he had founded and named after himself. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, August/September 2013]

There, Alexander was interred in at least two tombs in different locations, the more notable of which ancient authors, such as Strabo, Plutarch, and Pausanias, identify as a mausoleum called the Soma, meaning “body” in ancient Greek. The Soma was repeatedly robbed — the golden sarcophagus was melted down and replaced with one made of glass or crystal. Even Cleopatra took gold from the tomb to pay for her war against Octavian (soon to be the emperor Augustus). There were subsequent visits to the tomb by numerous Roman emperors and then, beginning in A.D. 360, a series of events that included warfare, riots, an earthquake, and a tsunami, threatened — or perhaps destroyed — the tomb by the time of Chrysostom’s visit. From that point on, Alexander’s tomb can be considered lost. And despite centuries of relentless searching by archaeologists, authors, and amateurs, it remains so.

Ptolemy I and the Corpse of Alexander the Great

Ptolemy I Soter (304-283 B.C.) took control of Egypt after Alexander the Great died. He was an ambitious self-made Macedonian general who served under Alexander and was also known as Ptolemy the savior. Ptolemy was crowned pharaoh in 304 B.C. on the anniversary of Alexander's death. He made offerings to the Egyptian gods, took an Egyptian throne name, and portrayed himself in pharaonic garb.

When Alexander died Ptolemy somehow got his hands of Alexander's embalmed corpse (some say he stole it as it was being shipped back to Macedonia for burial). The body had been embalmed with honey. Ptolemy put the corpse in class coffin and had it displayed to the public. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian magazine, June 1985]

Ptolemy brought Alexander's body to the northern coat of Egypt to shore up his claim on the region and boost his legitimacy. Ptolemy made Alexander's tomb into one of the world's first major tourist attractions and through it brought recognition to Alexandria. The corpse was exhibited in an elaborate mausoleum much as the bodies of Lenin and Mao are displayed in class cases in Moscow and Beijing. Tourist reportedly formed long lines to glimpse the famous Macedonian general's embalmed body. The body is thought to have remained there for six centuries and is thought to have maybe disappeared in riots in the A.D. 3rd century.

Discovery of the Tomb of Alexander the Great?

In February 1995, Greek archaeologist Liana Souvalzi claimed she had discovered the tomb of Alexander the Great at the Siwa Oasis in Egypt (near the Libyan border), 1,200 miles away from where the Macedonian general died in Babylon. Ruined by an ancient earthquake, the tomb consists of a 12-by-12 foot burial chamber with two antechambers and a corridor flanked by statues of two lions. The tomb, which is similar to the tomb of Alexander's father, Philip II, was identified by a tablet believed to have been written by Ptolemy I, describing how he brought the body from Alexandria.

After the announcement a Greek delegation toured the site and said there was no proof to corroborate Souvalzi's claim. A few years later funding of the excavation was stopped. The delegation claimed that what Souvaltzi found may not even be a tomb and that it appeared to have been built more than a century after Alexander's death. Souvaltzi's research was funded by her husband. She once said that she sought advice of where to look for promising site from snakes.

Alexander Sarcophagus

The Alexander Sarcophagus is a late 4th century B.C. Hellenistic stone sarcophagus from the Royal necropolis of Ayaa near Sidon, Lebanon. It is adorned with high relief carvings of Alexander the Great and scrolling historical and mythological narratives. The work is considered to be remarkably well preserved, and has been used as an exemplar for its retention of polychromy. It is currently at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. [Source Wikipedia]

Although it has been widely accepted that this was not the actual sarcophagus of Alexander the Great himself from early on in its analysis, there has been great scholarly debate surrounding who the patron of the sarcophagus was. It was originally thought to have been the sarcophagus of Abdalonymus (died 311 B.C.) the king of Sidon appointed by Alexander immediately following the Battle of Issus (333 B.C.). Scholars Andrew Stewart asserts that the Alexander Sarcophagus was patronized by Abdalonymus for a number of reasons: mainly, for the reason that Near Eastern kings regularly commissioned their tombs ante-mortem in consideration of their "posthumous reputations."

This is a commonly supported claim that has been continuously upheld by many scholars, but it has also been equally contested. For example, Waldemar Heckel argues that the sarcophagus was made for Mazaeus, a Persian noble and governor of Babylon. In order to support this assertion, Heckel questions why a sarcophagus for Abdalonymus, a king from Sidon, would feature so many Persian figures and iconographies, arguing that the dress, facial features, and activities of the central figure is more historically aligned with Persian rather than Phoenician nobility.

Different narratives decorate the friezes on each side and pediment of the sarcophagus. The relief carvings on one long side of the piece depict Alexander fighting the Persians at the Battle of Issus. Volkmar von Graeve has compared the motif to the famous Alexander Mosaic at Naples; he concludes that the iconography of both derives from a common original, a lost painting by Philoxenos of Eretria. The opposite long side shows Alexander, recognized as the "horseman at the center left," and the Macedonians hunting lions together with Abdalonymus and the Persians.

Plots and Grief After Alexander’s Death

Before his death, Alexander's troops, concerned he was already dead, demanded to see him. Arrian wrote: "Nothing could keep them from the sight of him, and the motive in almost every heart was grief of a sort of helpless bewilderment at the thought of losing their king. Lying speechless as the men filed by, he struggled to raise his head, and in his eyes there was a look of recognition for each individual he passed."

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “His passing was greeted very differently in different parts of his vastly enlarged empire. The traditional enemies of Macedon in Greece were thrilled to bits, whereas those Greeks and non-Greeks who had gladly worshipped him as a living god felt genuinely bereft. Whatever is thought of his lifetime achievements, there is no questioning the impact of his posthumous fame. [Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Roxanne and her son, Alexander IV, born six weeks after Alexander's death were murdered by a distant relative when the boy was 12 or 13. Alexander's mother Olympias was also killed. Plutarch wrote: “Roxana, who was now with child, and upon that account much honored by the Macedonians, being jealous of Statira, sent for her by a counterfeit letter, as if Alexander had been still alive; and when she had her in her power, killed her and her sister, and threw their bodies into a well, which they filled up with earth, not without the privity and assistance of Perdiccas, who in the time immediately following the king’s death, under cover of the name of Arrhidæus, whom he carried about him as a sort of guard to his person, exercised the chief authority.[Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Arrhidæus, who was Philip’s son by an obscure woman of the name of Philinna, was himself of weak intellect, not that he had been originally deficient either in body or mind; on the contrary, in his childhood, he had showed a happy and promising character enough. But a diseased habit of body, caused by drugs which Olympias gave him, had ruined not only his health, but his understanding.

Roxana with Alexander IV Aegus, son of Alexander the Great

Philip III Arrhidaios — Alexander the Great's half-brother and successor — and his young warrior-queen wife Eurydice, were respectively killed and forced to commit suicide by Olympias, Philip III's stepmother and Alexander’s mother. Historical texts say that Philip II was buried, exhumed, burned and re-buried: A royal tomb found in Greece containing the burned bones of a man and a young woman, some scholar believe, could belong to Philip III and Eurydice. Others say the entombed man is probably Philip II, Alexander the Great's father, making the woman in the tomb Cleopatra, Philip II's last wife (She is different from the famous Cleopatra). This Cleopatra also met a tragic end. She was either killed or forced to commit suicide by Olympias. Scholars are still debating issues whether the bones were burned dry or covered in flesh and viscera. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, April 8, 2011]

Alexander the Great's Legacy

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “Thanks above all to the literary text known as the Alexander Romance, created originally at the great leader's most famous foundation - the city of Alexandria, in Egypt - Alexander has featured internationally as a hero, a quasi-holy man, a Christian saint, a new Achilles, a philosopher, a scientist, a prophet, and a visionary. The more earthy musings of the hero of Shakespeare's Hamlet, in the graveyard scene, are just one chauvinistic illustration of the fact that Alexander has featured in the literature of some 80 countries, stretching from our own Britannic islands (as Arrian, called them) to the Malay peninsula - by way of Kazakhstan. |::|

“That is another way of saying that Alexander is probably the most famous of the few individuals in human history whose bright light has shot across the firmament to mark the end of one era and the beginning of another. One of our best sources on Alexander, Arrian, focused on one particular quality of Alexander, his pothos or overmastering desire to achieve or experience the humanly - and divinely - unprecedented. Alexander's hunt for what was in the end unattainable by him in his lifetime provides us with the chance, and the motive, to conduct a new hunt to try to capture the daunting immensity of his achievement. |::|

Pierre A. Zalloua of the American University of Beirut Medical Center is studying if the armies of Alexander the Great left behind a genetic legacy in places he conquered. Whether Alexander the Great is from the present-day countries of Greece or Macedonia is a divisive political issue between those two nations. Each claims Alexander as their own. In 2009, Macedonia raised eyebrows when it proposed building an eight-story-high statue of Alexander the Great in the center of its capital Skopje.

Alexander's Primary Legacy — Spreading Greek Culture

legend of the flying Alexander

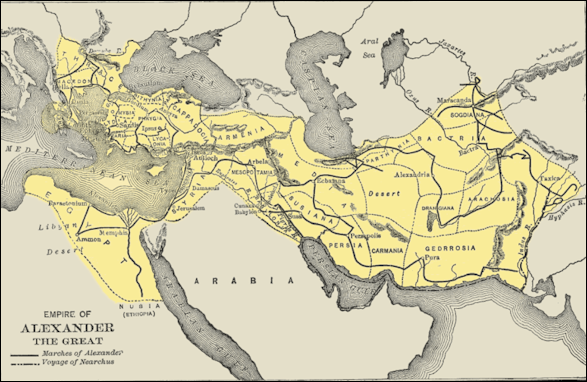

Alexander the Great's million-and-a-half square mile empire lasted for only a few decades after he died. "Alexander the Great's Empire fell, in part, because he treated his provincial subjects as defeated enemies," journalist T.R. Reid wrote in National Geographic. "The Romans treated their subjects as Romans — not outsiders but contributors." Yet Alexander must be given credit for spreading Greek culture to the corners of the known world at that time and ushering in the Hellenistic period. Arrian wrote that in one of his last speeches to his troops Alexander said "I set no limits of labors to a man of spirit, save only that the labors themselves...lead on to noble enterprises...It is a lovely thing to live with courage, and to die, leaving behind an everlasting renown."↔

Alexander is recognized for spreading Greek culture far into Asia, which in turn had an affect on government, art, literature and religion in places that had never heard of Greeks before. He Great founded 20 cities and unified the East and West. The cities helped disseminate Greek culture. He is also is credited with exposing Greece and the Western to Eastern culture. Some say he helped civilize the Persians, Sogdians and others. Of the six cities established by Alexander only Alexandria remains.

Borcas, the Greek god of the west wind, was adopted by local people and made its way westward as far as Japan, where he became Fujin, the Japanese god of wind. As he moved eastward Borcas exchanged his wings for a veil as he became Vado the wind god in ancient Kushan in Pakistan. Greek-influenced images of the Buddhist gods Vaisravana and Majakala have been found in Pakistan. Images of Greek soldiers have been found in China.

Lost City of Alexander the Great?

The archaeological world was excited in the fall of 2017 with the news that a “Lost City of Alexander the Great” had been discovered in Iraq by an archaeological team of researchers from the British Museum reviewing declassified American spy footage obtained by drones during the 1960s Corona Project. Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast, The images appeared to show the outline of a square building — possibly an ancient fort — on the banks of Lake Dokan. Ground inspections uncovered limestone blocks that may have served as part of an oil or wine press. The innovative use of drones by the researchers, led by John McGinnis, made it possible to see the outlines of buildings and get the bigger picture that a close-up of the landscape obscured. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 1, 2017]

The city itself is located in the Qalatga Darband settlement, a naturally fortified plateau that overlooks a natural lake (which has been enlarged since ancient times by the addition of a dam). Dr. Robert Cargill, an archeologist at the University of Iowa, told The Daily Beast that the city guards “strategic pass between two mountain ranges that separate the ancient territories of Assyria and Media, both of which later became part of Alexander the Great’s vast empire. A naturally-defended fortress with fresh water in the mountains overlooking two strategic plains is an important site.” McGinnis, who headed up the excavation, describes that the site as “a bustling city on a road from Iraq to Iran… You can image people supplying wine to the soldiers passing through.”

Wall painting in Acre

Some archaeologists have dated the founding of the city to 331 B.C., the height of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the ancient Mediterranean world. Dr. Diane Cline, an associate professor of classics and history at George Washington University told The Daily Beast, “The location in northern Iraq suggests that the date of the foundation of this site must be in 331 B.C.. The battle of Gaugamela was fought close to Erbil on October 1, 331 — we know that date because of an eclipse recorded 11 days earlier — and Alexander might have created the town as an outpost, a place to leave his wounded men and older veterans.” It must have been founded around then, Cline adds, because “by the end of October 331 Alexander had moved on to Babylon.”

The closest other Alexandrias to this one, Cline told me, are the famous Alexandria of Egypt, which was founded on April 7 331 B.C., and the colony under Heat in Afghanistan, founded in September 330 B.C.. The Alexandria in Egypt, of course, is famous to this day for its lighthouse and library. It was not only of importance to Hellenistic (Greek-speaking) Egyptians, it was the home of the famous first century Jewish philosopher Philo and in the second and third centuries would later house one of the most influential early Christian “schools” (a cross between a university and a think tank).

That the site was inhabited by Hellenistic-era Greeks is beyond a shadow of a doubt. The archeological team has released the details of distinctive coins, Greco-Roman architectural elements, marble figures, and bronze vessels that demonstrate this. But none of the evidence released so far proves that Alexander the Great founded the city or dates it earlier than the second century B.C..

As a result, some scholars are cautious about the claims being made about this site. Dr. Christopher Baron, associate professor of Classics at the University of Notre Dame, told The Daily Beast that there is no evidence linking Alexander to the site. The city is located about 60 miles east of the present Kurdish capital Erbil (ancient Arbela), near where Alexander and his Macedonian army defeated the forces of the last Persian king Darius III on October 1, 331 B.C. (the Battle of Gaugamela). So far so good, says Baron.

This is where things get tricky. Baron told The Daily Beast that after the battle, according to our ancient sources, Darius fled first to Arbela, then east through the mountains toward Ecbatana (modern Hamadan, Iran). “This would have taken Darius through the pass where Qalatga Darband sits. But Alexander, rather than pursue Darius, marched south along the Tigris River in order to capture the magnificently rich cities of Babylon and Susa.”

From then Alexander moved on to Southern and, later, Northern Iran. “Just about every report on the new find gets this wrong,” says Baron, “they have Alexander pursuing Darius through the pass between Erbil and Hamadan, where Qalatga Darband sits. But Alexander did not go further east from Arbela/Erbil… So, most likely, Alexander himself never set foot in Qalatga Darband.” Add to this the fact that the only datable archeological evidence that we know about from the site (the Parthian coin) is first century B.C. and the connection with Alexander weakens. As Baron puts it, “As far as I can see, the only direct connection with Alexander is that he won his most important battle nearby.”

The problem, Baron notes, may be an issue of reporting. The archaeological project’s website does not mention Alexander the Great at all, and original analysis of the site dated it to the second or first century B.C. to the Seleucid or Parthia empires. McGinnis himself, a highly talented archaeologist, has remarked that it is “early days” for research into the site and does not seem to have made the connection with Alexander himself.

Alexander-Hercules Temple Found On Top of a Sumerian Temple in Iraq

hoplite In 2023, archaeologists announced that they had discovered two temples, one buried atop the other, in the ancient city of Girsu in southern Iraq. British Museum experts said the older temple may have been where Alexander the Great may proclaimed divine and the other where he was worshiped after his death. The latter temple contained a fired brick with an Aramaic and Greek inscription that references "the giver of two brothers" — a possible reference to Alexander the Great. The temple is linked to Hercules and Alexander.. [Source Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, December 8, 2023]

Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph: Experts working at Girsu unearthed a 4,000-year-old Sumerian temple, so old that later extremely cryptic Greek inscriptions found at the site made no historical sense. British Museum archaeologists now believe the site boasted a Greek temple possibly commissioned by Alexander the Great himself to honour ancient gods and his own divine status. If the theory is correct, it may have been one of the last acts of the conqueror before his death at age 32. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 19, 2023]

The discovery of the temple also suggests that Alexander’s contemporaries had knowledge of the previous 4,000-year-old site which had been abandoned for millennia, suggesting that ancient societies had an accurate historical knowledge and cultural memory. British Museum archaeologist Dr Sebastien Rey said: “It is truly mind-blowing. Our discoveries place the later temple in Alexander’s lifetime. We found offerings, the kinds of offerings that would be given after a battle, figures of soldiers and cavalrymen. There is a chance, we will never know for certain, that he might have come here, when he returned to Babylon, just before he died. This site honours Zeus and two divine sons. The sons are Heracles and Alexander.”

Girsu was likely inhabited from 5000 B.C. and by the 3rd millennium B.C. was a city sacred to the Sumerians, the world’s first civilization, as the home of their warrior god Ningirsu. The site being excavated by the British Museum’s Girsu Project, funded by Getty, was abandoned in 1750 B.C., more than 1,000 years before the Macedonian king Alexander was born. It appeared that a Greek structure may have been built on the site, but there were no clues beyond a tablet written in Aramaic and Greek that simply stated “Adad-nadin-a e”, which means “giver of the two brothers”.

The British Museum expedition may have solved this mystery, after finding a silver drachma coin minted by Alexander’s men in the 330s B.C., within the lifetime of Alexander the Great and immediately after he had defeated the Persians who ruled over the region. They also found an altar and figurines which would typically have been left at Greek temples as offerings, including the coin, suggesting that this was a place of worship. These offerings took the form of terracotta cavalrymen similar to those in the Companion Cavalry which formed Alexander’s bodyguard, suggesting that whoever left votive offerings there was extremely close to the commander, if not the general himself.

Alexander was obsessed with mythical strongmen, and in Egypt had himself declared the Son of Zeus, thereby becoming the brother of his hero Hercules. Hercules has similarities with the far more ancient figure of Ningirsu, including the completion of Twelve Labours. Dr Rey believes that Alexander may have asked the people of Mesopotamia who their equivalent to Hercules was and been told that it was Ningirsu, making the general the brother of this fused Greek and Sumerian deity.

If he then sought a sacred site to honour him, those with the knowledge of Girsu as the home of the god would have directed him there. The cryptic inscription “giver of the two brothers”, Dr Rey believes, refers to Alexander’s purported father Zeus, who had given the world both the commander and his brothers Hercules and Ningirsu. The fact that local people knew that Girsu, which had been abandoned more than 1,000 years before, was the home of the god Ninrusu suggests “deep cultural memory”, Dr Rey said. The archaeologist has suggested that there is a chance that the later Hellenistic temple placed on top of the older sacred site was founded when Alexander passed through the region near Girsu on his return from campaign in India, a march which took place just before his death in 323 B.C.. Dr Rey said: “This site honours Zeus and two divine sons. The sons are Heracles and Alexander. That is what these discoveries suggest.”

The silver drachm (an ancient Greek coin) was buried beneath the altar or shrine, as well as a brick with the two brothers inscription."The inscription is very interesting because it mentions an enigmatic Babylonian name written in Greek and Aramaic," Rey told Live Science. "The name 'Adadnadinakhe,' which means 'Adad, the giver of brothers,' was clearly chosen as a ceremonial title on account of its archaizing tone and symbolic connotations. All the evidence points to the fact that the name was extraordinarily rare." The inscription itself is a nod to Zeus, the Greek sky god, who is often symbolized by a lightning bolt and an eagle. Both of these symbols can be found on the coin, which would've been struck in Babylon "under Alexander the Great's authority," Rey said. "It shows Hercules in a youthful, clean-shaven portrait that strongly recalls conventional representations of Alexander on one side, with Zeus on the other." Zeus also "famously acknowledged Alexander as his son through the agency of the Ammon oracle,” Rey said. "He became quite literally the 'giver of brothers' because he affirmed a fraternal bond between Alexander and Heracles."

Colony of Macedonian Soldiers in Western Anatolia

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Inhabited as a colonial city by Macedonian soldiers in the third century B.C., the hilltop settlement of Blaundos in western Anatolia is surrounded by a deep canyon on all sides into which its inhabitants carved hundreds of burial chambers. Although the necropolis has been known for centuries, it is only recently that a team led by archaeologist Birol Can of Uşak University has begun to systematically investigate the unexplored tombs. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Alexander's empire

In 2021, the team documented around 400 burials dug into the canyon walls. According to Can, the chambers were initially built as single rooms and some were expanded over the generations to make room for sarcophagi holding additional family members. Some eventually held as many as 30 burials. Coins and pottery fragments found in the tombs, as well as the style and iconography of frescoes covering many of their walls and ceilings, indicate that the burials date to the Roman period, from the second to fourth century A.D. The intricate, colorful frescoes, which depict plants and flowers, animals such as birds and dogs, and mythological characters, have deteriorated over the centuries due to causes including illegal excavations, water damage, and fires set by shepherds who used the chambers to house their animals.

There are hundreds of additional tombs still to be excavated, including many that likely date to earlier in Blaundos’ history. “The fact that the whole city was surrounded by the tombs of the Blaundians’ ancestors must have given them spiritual confidence,” says Can. “We can guess that people regularly visited the necropolis during the period when it was used.”

Kalash — Descendants of Alexander the Great?

The Kalash (Kalasha, Kafir-Kalash , Kafir-Kalaish) — a tiny tribe that lives near the Afghanistan border in the Birir, Bumburet and Rambur valleys off of the Chistral Valley in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan — claim they are descendants of five of Alexander the Great's warriors. One of a handful of groups that claim Alexander's army to be their ancestors, the Kalash relate a story of Alexander's bacchanal with mountain dwellers claiming descent from Dionysus. "They were likely the forbears of the Kalash, who still worship a pantheon of gods, make wine, practice animal sacrifice — and resist conversion to Islam." [Source: "People of Fire and Fervor", Debra Denker, National Geographic, October 1981 ♂]

The Kalash are famous for the their pagan beliefs and strange costumes. The women wear black robes, dozens of red bead necklaces and cowrie-shell head-dresses that look like a carpet with paint brushes, feathers or flowers sprouting from the head. The Kalash are also known for their lewd songs, provocative dances and partying ways.

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “In contrast to most Pakistanis, who tend to be swarthy, most Kalash men and women have pale skin; many are blond and some are redheaded. They have aquiline noses and blue or gray eyes, the women outlining them with black powder from the ground-up horns of goats. "Wherever Alexander passed, he left soldiers to marry local women and establish outposts of his empire," a guide says. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, January 2007]

“That contention, oft repeated in these parts, has recently gotten scientific support. Pakistani geneticist Qasim Mehdi, working with researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine, has found that Kalash blood, unlike that of other Pakistani peoples, shares DNA markers with that of Germans and Italians. The finding tends to support descent from Alexander's troops, Mehdi said, because the general welcomed troops from other parts of Europe into his army.”

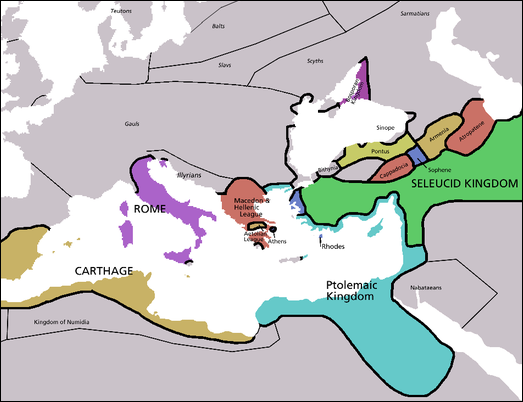

Europe and the Near East After Alexander's Death

Although Alexander’s armies passed through the Chitral region there is little evidence that they reached the remote valleys where the Kalash live today. The stories linking the Kalash to Alexander the Great seem to have been mostly attached to them by outsiders. Scholars and villagers say that neither the tribe’s written history nor its oral traditions, including song and poetry, mention reference to Alexander.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024