Home | Category: Alexander the Great

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S PERSONAL LIFE AND MARRIAGES

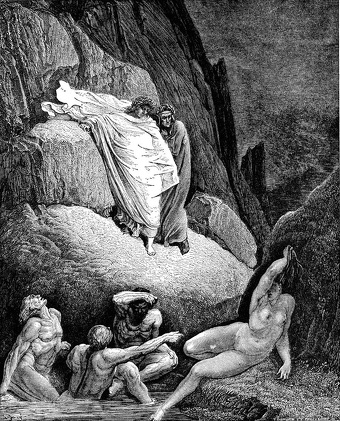

Marriage of Alexander and Roxana in the Villa Farnesina in Rome

Alexander III of Macedon — Alexander the Great (356 to 324 B.C.) — was perhaps the greatest conqueror of all time. In 334 B.C., at the age of 21, he left the small Greek of Kingdom of Macedonia with 43,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 horsemen to seek revenge against the Persian empire, which had sacked Greece and Macedonia and burnt Athens a century before, and didn't stop until he conquered much of the known world at that time. [Sources: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, November 2004; Caroline Alexander, National Geographic, March 2000; Helen and Frank Schreider, National Geographic, January 1968. [↔]

Although he was married twice some historians claim Alexander was a homosexual who was in love with his childhood friend, closest companion and general — Hephaestion. Another lover was a Persian eunuch named Bagoas. But many say that his truest love was his horse Bucephalas.

On his march of conquest, Alexander became entranced with a Songdian princess named Roxanne after she was captured in a siege of a Sogdian fortress. Arrian described her as “the loveliest woman in Asia after Darius's wife." Alexander married Roxanne in 327 B.C., apparently for love but also to give his presence in Asia some legitimacy. Alexander's second wife was a daughter of his arch-enemy Darius.

Alexander fathered a son with Roxanne, and perhaps another one with his Persian mistress, but sex didn't seem to have been a big part of his life. He once reportedly said, “Sex and sleep alone make me conscious that I am mortal." Roxanne died in 311. His son Alexander IV died in 310.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356 TO 324 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S APPEARANCE, CHARACTER, PERSONALITY AND HABITS factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S EARLY LIFE factsanddetails.com ;

PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OLYMPIAS (ALEXANDER’S THE GREAT'S MOTHER) europe.factsanddetails.com

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND ARISTOTLE europe.factsanddetails.com

PLOTS, SUSPICIONS, INTRIGUES, MURDERS, EXECUTIONS AND ALEXANDER THE GREAT factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Alexander the Great: His Life and His Mysterious Death” by Anthony Everitt (2019) Amazon.com;

“Alexander's Lovers” by Andrew Chugg (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Conqueror's Wife: A Novel of Alexander the Great” by Stephanie Marie Thornton (2020) Amazon.com;

“Roxana and Alexander” by Helga Moray (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Romance of Alexander and Roxana” by Marshall Monroe Kirkman (1842-1921), Novel Amazon.com;

“Alexander & Hephaestion: Their Lives and Unique Love as Recorded by Plutarch, Diodorus, Justin and Others” by Michael Hone (2018) Amazon.com;

“Young Conquerors: A Novel of Hephaestion and Alexandros” by Christopher Cosmos, Gary Bennett, et al. Amazon.com;

“The Persian Boy” by Mary Renault (1972), novel about Alexander the Great’s last years Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Alexander” by Mary Renault (1975) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Robin Lane Fox (1973) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life” by Thomas R. Martin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

Primary Sources:(Also available for free at MIT Classics, Gutenberg.org and other Internet sources):

“History of Alexander” by Quintus Curtius Rufus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica” by Arrian (Oxford World Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander” by Arrian Amazon.com;

“The Life of Alexander the Great” by Plutarch (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

Alexander the Great’s Marriage to Roxana

Roxana was the daughter of a chief in Bactria, an area in Central Asia. Alexander's forces captured her while campaigning in the region and she married him in around 327 B.C. But Alexander didn't live to see their son; She was pregnant with Alexander IV when Alexander died in Babylon in 323 B.C. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 9, 2023]

Alexander married Roxana (Roshanak), the daughter of the most powerful of the Bactrian chiefs (Oxyartes, who revolted in present-day Tajikistan). Arrian wrote: “The wives and children of many important men were there captured, including those of Oxyartes. This chief had a daughter, a maiden of marriageable age, named Roxana, who was asserted by the men who served in Alexander’s army to have been the most beautiful of all Asiatic women, with the single exception of the wife of Darius. They also say that no sooner did Alexander see her than he fell in love with her; but though he was in love with her, he refused to offer violence to her as a captive, and did not think it derogatory to his dignity to marry her. This conduct of Alexander I think worthy rather of praise than blame. Moreover, in regard to the wife of Darius, who was said to be the most beautiful woman in Asia, he either did not entertain a passion for her, or else he exercised control over himself, though he was young, and in the very meridian of success, when men usually act with insolence and violence. On the contrary, he acted with modesty and spared her honour, exercising a great amount of chastity, and at the same time exhibiting a very proper desire to obtain a good reputation.”[Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

Claire Bloom as Barsine, and Richard Burton as Alexander the Great, in 1956 fim "Alexander the Great"

Plutarch connected a story about an Amazon with Alexander’s marriage to Roxana. He wrote: ““Here many affirm that the Amazon came to give him a visit. So Clitarchus, Polyclitus, Onesicritus, Antigenes, and Ister, tell us. But Aristobulus and Chares, who held the office of reporter of requests, Ptolemy and Anticlides, Philon the Theban, Philip of Theangela, Hecatæus the Eretrian, Philip the Chalcidian, and Duris the Samian, say it is wholly a fiction. And truly Alexander himself seems to confirm the latter statement, for in a letter in which he gives Antipater an account of all that happened, he tells him that the king of Scythia offered him his daughter in marriage, but makes no mention at all of the Amazon. And many years after, when Onesicritus read this story in his fourth book to Lysimachus, who then reigned, the king laughed quietly and asked, “Where could I have been at that time?”[Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“As for his marriage with Roxana, whose youthfulness and beauty had charmed him at a drinking entertainment, where he first happened to see her, taking part in a dance, it was, indeed, a love affair, yet it seemed at the same time to be conducive to the object he had in hand. For it gratified the conquered people to see him choose a wife from among themselves, and it made them feel the most lively affection for him, to find that in the only passion which he, the most temperate of men, was overcome by, he yet forbore till he could obtain her in a lawful and honorable way.”

Alexander and 10,000 of His Troops Marry Persians

In 324 B.C., after the conquests were over and Alexander was in Babylon in Persia, Alexander commanded his officers and 10,000 of his soldiers to marry Iranian women. The mass wedding, held at Susa (Shush, Iran), was a model of Alexander's desire to consummate the union of the Greek and Iranian peoples. At this time Alexander took a second wife, Barsine, a daughter of Darius. Eighty of his officers married daughters of Persian nobles. Arrian wrote: “In Susa also he celebrated both his own wedding and those of his companions. He himself married Barsine, the eldest daughter of Darius, and according to Aristobulus, besides her another, Parysatis, the youngest daughter of Ochus. He had already married Roxana, daughter of Oxyartes the Bactrian. To Hephaestion he gave Drypetis, another daughter of Darius, and his own wife’s sister; for he wished Hephaestion’s children to be first cousins to his own. To Craterus he gave Amastrine, daughter of Oxyartes the brother of Darius; to Perdiccas, the daughter of Atropates, viceroy of Media; to Ptolemy the confidential body-guard, and Eumenes the royal secretary, the daughters of Artabazus, to the former Artacama, and to the latter Artonis. To Nearchus he gave the daughter of Barsine and Mentor; to Seleucus the daughter of Spitamenes the Bactrian. [Source: Arrian the Nicomedian (A.D. 92-175), “Anabasis of Alexander”, translated, by E. J. Chinnock, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884, gutenberg.org]

Likewise to the rest of his Companions he gave the choicest daughters of the Persians and Medes, to the number of eighty. The weddings were celebrated after the Persian manner, seats being placed in a row for the bridegrooms; and after the banquet the brides came in and seated themselves, each one near her own husband. The bridegrooms took them by the right hand and kissed them; the king being the first to begin, for the weddings of all were conducted in the same way. This appeared the most popular thing which Alexander ever did; and it proved his affection for his Companions. Each man took his own bride and led her away; and on all without exception Alexander bestowed dowries. He also ordered that the names of all the other Macedonians who had married any of the Asiatic women should be registered. They were over , in number; and to these Alexander made presents on account of their weddings.”

Alexander the Great’s Children

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Alexander had one and possibly even two children — both sons. One, known as Alexander IV, was his son with his wife Roxana. Alexander didn't live to see him. Roxana was pregnant with Alexander IV when he died in Babylon in 323 B.C. The other, known as "Heracles of Macedon," was his son with Barsine, his Persian wife or mistress.[Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, July 9, 2023]

"Heracles of Macedon" was born to Barsine, a Persian noblewoman, around 327 B.C., making him about four years older than Alexander IV. Some scholars in modern times question whether Alexander was actually the father of Barsine, as Alexander never formally acknowledged the child. But there appears to be a consensus among some modern scholars that Heracles was his biological son. "[A] few historians are skeptical of Alexander's paternity, but I do not share their view," Joseph Roisman, an emeritus professor of classics at Colby College in Maine, told Live Science.

After Alexander the Great died of a mysterious illness at age 32, there was no clear successor for his massive empire. His wife was pregnant with Alexander IV, although at the time it was not known if the child was a boy or girl. Heracles of Macedon was not legitimate, making his claim to the throne more difficult. "The boy was never a contender to succeed him because he was illegitimate and the son of a mistress," professor Ian Worthington told Live Science.

Additionally, both Roxana and Barsine were of Asian ancestry, which some of Alexander's troops did not like. "According to the ancient [Roman] Alexander historian Quintus Curtius, both sons were proposed as potential heirs to the throne in a meeting of the generals and cavalry class, but the army rank and file — infantry — rejected both because the mothers were Asian," Carol King, an associate professor of classics at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, told Live Science.

Arrhidaeus, the half brother of Alexander the Great, became king and Alexander IV was made a co-ruler after he was born. However, "neither 'king' could rule in practice, of course," King said. Arrhidaeus had some form of mental impairment that made it difficult for him to exercise power while Alexander IV was just an infant. As a result, "all became pawns in the wars of the successors, Alexander's powerful generals, as they fought each other for control of the empire; and all were murdered," King said, referring to Arrhidaeus and Alexander's children.

Alexander the Great's mother, Olympias, took on a significant role in the power struggle. In 317 B.C., she agreed to become the guardian of Alexander IV and, with the help of an army led by a general named Polyperchon, captured Arrhidaeus and had him killed, wrote Robin Waterfield, in "Dividing the Spoils: 'The War for Alexander the Great's Empire". However, a force led by a general named Cassander attacked Olympias and captured her along with Alexander IV in 316 B.C. and had Olympias killed.

Alexander IV and Roxana then found themselves captives of Cassander, who effectively controlled Macedonia as a king. Cassander didn't want any competition for the throne, so he had Alexander IV and Roxana killed around 309 B.C., to prevent the teenage heir from coming of age and potentially taking power. Heracles of Macedon didn't fare any better. The general Polyperchon took Alexander's illegitimate son captive, and, after reaching a deal with Cassander, had him killed shortly after Alexander IV's death, Waterfield wrote.

Thaïs — Ptolemy’s and Possibly Alexander's Mistress

Thaïs was a Greek hetaira (a type of courtesan or prostitute in ancient Greece) who accompanied Alexander the Great on his military campaigns. Likely from Athens, she is most famous for having instigated the burning of Persepolis, the capital city of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, after it was conquered by Alexander's army in 330 BCE. At the time, Thaïs was the lover of Ptolemy I Soter, who was one of Alexander's close companions and generals. [Source Wikipedia]

It has been suggested that she may also have been Alexander's lover on the basis of a statement by the Greek rhetorician Athenaeus, who writes that Alexander liked to "keep Thaïs about him" without directly classifying the nature of their relationship as intimate; this may simply have meant that he enjoyed her company, as she is said to have been very witty and entertaining. Athenaeus also states that after Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Thaïs married Ptolemy and bore three of his children.

Persepolis was the principal residence of the defeated Achaemenid dynasty. At a drinking party, one story goes, Thaïs was gave a speech which convinced Alexander to burn the palace in Persepolis. Cleitarchus claims that the destruction was a whim; Plutarch and Diodorus assert that it was intended as retribution for Xerxes' burning of the old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens in 480 B.C. during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It has been argued that Thaïs was Alexander's lover at this time. T. D. Ogden suggests that Ptolemy took her over at some later point, though other writers believe she was always Ptolemy's companion

Diodorus of Sicily wrote (XVII.72): When the king [Alexander] had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honour of Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out for the comus to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thaïs the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport.

Partying with Alexander and Thaïs

After leaving Susa, the capital of Persian, and seeking Darius set aside some time to enjoy himself. Plutarch wrote: “From hence designing to march against Darius, before he set out, he diverted himself with his officers at an entertainment of drinking and other pastimes, and indulged so far as to let every one’s mistress sit by and drink with them. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

The most celebrated of them was Thais, an Athenian, mistress of Ptolemy, who was afterwards king of Egypt. She, partly as a sort of well-turned compliment to Alexander, partly out of sport, as the drinking went on, at last was carried so far as to utter a saying, not misbecoming her native country’s character, though somewhat too lofty for her own condition. She said it was indeed some recompense for the toils she had undergone in following the camp all over Asia, that she was that day treated in, and could insult over, the stately palace of the Persian monarchs. But, she added, it would please her much better, if while the king looked on, she might in sport, with her own hands, set fire to the court of that Xerxes who reduced the city of Athens to ashes, that it might be recorded to posterity, that the women who followed Alexander had taken a severer revenge on the Persians for the sufferings and affronts of Greece, than all the famed commanders had been able to do by sea or land.

“What she said was received with such universal liking and murmurs of applause, and so seconded by the encouragement and eagerness of the company, that the king himself, persuaded to be of the party, started from his seat, and with a chaplet of flowers on his head, and a lighted torch in his hand, led them the way, while they went after him in a riotous manner, dancing and making loud cries about the place; which when the rest of the Macedonians perceived, they also in great delight ran thither with torches; for they hoped the burning and destruction of the royal palace was an argument that he looked homeward, and had no design to reside among the barbarians. Thus some writers give their account of this action, while others say it was done deliberately; however, all agree that he soon repented of it, and gave order to put out the fire.”

Grave of a Courtesan of Alexander’s Army Possibly Unearthed

In 2023, it was reported that cremated remains found with an ornate 2,300-year-old bronze mirror in Israel may have belonged to a Greek courtesan who accompanied Alexander the Great's army. Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: The woman was buried on the road to Jerusalem far from any settlement, suggesting she may have been a professional escort, or "hetaira," traveling with military men. "It is most likely that this is the tomb of a woman of Greek origin who accompanied a senior member of the Hellenistic army or government," the researchers said in a statement. Her client may have fought in one of Alexander the Great's campaigns, they added, or in a series of conflicts called the Wars of the Diadochi, which saw Alexander's generals battle to succeed him after he died in 323 B.C. [Source Sascha Pare, Live Science, October 3, 2023]

The woman was 20 to 30 years old when she died, researchers told the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, and her remains indicate she was cremated before being buried alongside a "very precious" bronze mirror and four iron nails. The mirror is enclosed in a folding box of a type previously found in Greco-Hellenistic burials, hinting at the woman's Greek origin. While these accessories often feature engravings or reliefs of idealized female and goddess figures, the newly discovered object is decorated on the outside with a simpler pattern of concentric circles. "This is only the second mirror of this type that has been discovered to date in Israel," Liat Oz, an archaeologist who led the recent excavation in Jerusalem's Talpiot neighborhood on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in the statement. The hetaira may have received it as a gift from her powerful client, the researchers said.

Women also acquired bronze mirrors as part of their dowry — but married women at the time seldom left their homes in Greece, let alone joined their husbands on military campaigns, the researchers added. Historic records indicate courtesans were present during Alexander the Great's campaigns, the researchers told Haaretz. They provided sexual services, but were also literate and entertained their clients with poetry, dance and acting performances. "We know that some joined generals or rulers on their campaigns — famously, the hetaira Thaïs joined Alexander on the road and he didn't like her to be far," Guy Stiebel, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University who participated in the recent excavation, told Haaretz. The iron nails discovered in the roadside grave were likely credited with "magical powers," he added, such as warding off the evil eye and preventing the deceased from rising again. Nails are frequently found in ancient Greek and Roman graves, as well as in Jewish burials from the time.

"We know [the hetairai] were buried on roadsides," archeologist Dr. Guy Stiebel of Tel Aviv University told Haaretz. "Alexander of Macedonia was even criticized for investing not in graves for Greek soldiers who fell in the war against Persia, but for his hetairai, on the main road, from a point where they could see Athens and the Parthenon for the first time. Maybe we can, cautiously, see a correlation here...We know from historic records that this was happening and we know that some joined generals or rulers on their campaigns — famously, the hetaira Thais joined Alexander on the road and he didn’t like her to be far. When they conquered Persepolis, Thais was the one who some say stood behind the decision to burn the city to the ground," he added.

Hephaestion — Alexander the Great’s Best Friend

Hephaestion was Alexander the Great’s oldest and dearest friend. Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Hephaestion had been Alexander’s close friend from childhood, probably taught by Aristotle alongside the young prince. The two were close in age, with sources putting Hephaestion’s birth in 357 or 356 B.C., and some historians believe the two were lovers as young men. [Source: Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, September 27, 2018]

One popular account puts the comrades near the river Granicus in Anatolia (modern Turkey) on the way to battle the Persian army in 334. Alexander visited the tomb of Achilles, his alleged ancestor, while Hephaestion paid his respects to Patroclus, Achilles’ dear companion. The two were said to look so alike that they were often mistaken for one another. Hephaestion stayed in Alexander’s favor throughout his career. His sudden death in 324 B.C. deeply affected Alexander, who openly mourned his lifelong friend.

In Ecbatana, in western Iran, Hephaestion died, causing Alexander to be overcome with tremendous grief. Plutarch wrote: “When he came to Ecbatana in Media, and had despatched his most urgent affairs, he began to divert himself again with spectacles and public entertainments, to carry on which he had a supply of three thousand actors and artists, newly arrived out of Greece. But they were soon interrupted by Hephæstion’s falling sick of a fever, in which, being a young man and a soldier too, he could not confine himself to so exact a diet as was necessary; for whilst his physician Glaucus was gone to the theatre, he ate a fowl for his dinner, and drank a large draught of wine, upon which he became very ill, and shortly after died. At this misfortune, Alexander was so beyond all reason transported, that to express his sorrow, he immediately ordered the manes and tails of all his horses and mules to be cut, and threw down the battlements of the neighboring cities. The poor physician he crucified, and forbade playing on the flute, or any other musical instrument in the camp a great while, till directions came from the oracle of Ammon, and enjoined him to honor Hephæstion, and sacrifice to him as to a hero. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

See Death of Hephaestion, Alexander’s Best Friend Under DEATH OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT europe.factsanddetails.com

Were Alexander the Great and Hephaestion Lovers?

From of the Stag Hunt Mosaic, 300 BC, from Pella; the figure on the right might be Alexander the Great due to the date of the mosaic, along with the depicted upsweep of his centrally-parted hair; the figure on the left is wielding a double-edged axe which is associated with Hephaistos, meaning perhaps it is Hephaestion

The release of a Netflix docudrama “Alexander: The Making of a God’, which took a look at Alexander the Great’s relationship with Hephaestion, briught some attention to the issue of whether they were more than just friends. Parissa Djangi wrote in National Geographic: Sexual relationships between men were common among elites in ancient Macedonia. Alexander likely “participated in the martially-driven bisexual culture of the Macedonian court,” according to historian Daniel Ogden. [Source: Parissa Djangi, National Geographic, February 8, 2024]

At the same time, ancient writers didn’t conclusively identify Alexander and Hephaestion as lovers. One hint came from Claudius Aelianus, a third-century Roman writer, who claimed Hephaestion“was the object of Alexander’s love,” though he was writing approximately 550 years after Alexander’s death. Due to this lack of certainty, modern scholars hesitate to precisely define Alexander and Hephaestion’s relationship. Nonetheless, many conclude they may have been lovers.

We know that Alexander elevated Hephaestion to “chiliarch,” a position second only to Alexander himself, around 330 B.C. He also reportedly hoped to formalize his relationship to Hephaestion through kinship ties. According to Arrian, Alexander married Hephaestion to his wife’s sister Drypetis so “that Hephaestion’s children should be joined in affinity with his own.” Fate snuffed out Alexander’s plans when Hephaestion fell ill and unexpectedly died in October 324 B.C.<br

Bagoas — The Beautiful Eunuch Who Became Alexander's Lover?

In Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea, Alexander was given a beautiful eunuch named Bagoas, who became Alexander's lover. This move was not popular with his men. Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Bagoas first met Alexander following the death of Darius III. He had been sent on behalf of Nabarzanes, a Persian military officer who had helped slay Darius, and whom Alexander — as Darius’s successor — could consider punishing as a murderer of his king. [Source: Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, September 27, 2018]

Writing in the first century A.D., Quintus Curtius Rufus wrote in that Bagoas was “of uniquely lovely looks,” argued successfully that Nabarzanes be pardoned and later became Alexander’s lover. The implication that Alexander’s judgment was swayed by Bagoas’s looks was later echoed by Plutarch, who wrote of Alexander’s enthusiastic response to Bagoas’s dancing.

Another source, Arrian of Nicomedia, however, generally portrays Alexander as able to resist his attraction to Bagoas. Some historians argue that Bagoas’s plea to Alexander was strengthened by his knowledge of the case, and the fact he spoke Greek. In other words, looks aside, Bagoas was probably the best negotiator for the job.

Alexander’s Acts of Kindness and Friendship

Alexander with the family of Darius

On how Alexander treated his friends, Plutarch wrote: “Meantime, on the smallest occasions that called for a show of kindness to his friends, there was every indication on his part of tenderness and respect. Hearing Peucestes was bitten by a bear, he wrote to him, that he took it unkindly he should send others notice of it, and not make him acquainted with it; “But now,” said he, “since it is so, let me know how you do, and whether any of your companions forsook you when you were in danger, that I may punish them.” He sent Hephæstion, who was absent about some business, word how while they were fighting for their diversion with an ichneumon, Craterus was by chance run through both thighs with Perdiccas’s javelin. And upon Peucestes’s recovery from a fit of sickness, he sent a letter of thanks to his physician Alexippus. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

When Craterus was ill, he saw a vision in his sleep, after which he offered sacrifices for his health, and bade him to do so likewise. He wrote also to Pausanias, the physician, who was about to purge Craterus with hellebore, partly out of an anxious concern for him, and partly to give him a caution how he used that medicine. He was so tender of his friends’ reputation that he imprisoned Ephialtes and Cissus, who brought him the first news of Harpalus’s flight and withdrawal from his service, as if they had falsely accused him. When he sent the old and infirm soldiers home, Eurylochus, a citizen of Ægæ, got his name enrolled among the sick, though he ailed nothing, which being discovered, he confessed he was in love with a young woman named Telesippa, and wanted to go along with her to the seaside. Alexander inquired to whom the woman belonged, and being told she was a free courtesan, “I will assist you,” said he to Eurylochus, “in your amour, if your mistress [214] be to be gained either by presents or persuasions; but we must use no other means, because she is free-born.”

“It is surprising to consider upon what slight occasions he would write letters to serve his friends. As when he wrote one in which he gave order to search for a youth that belonged to Seleucus, who was run away into Cilicia; and in another, thanked and commended Peucestes for apprehending Nicon, a servant of Craterus; and in one to Megabyzus, concerning a slave that had taken sanctuary in a temple, gave direction that he should not meddle with him while he was there, but if he could entice him out by fair means, then he gave him leave to seize him. It is reported of him that when he first sat in judgment upon capital causes, he would lay his hand upon one of his ears while the accuser spoke, to keep it free and unprejudiced in behalf of the party accused. But afterwards such a multitude of accusations were brought before him, and so many proved true, that he lost his tenderness of heart, and gave credit to those also that were false; and especially when anybody spoke ill of him, he would be transported out of his reason, and show himself cruel and inexorable, valuing his glory and reputation beyond his life or kingdom.”

Alexander’s View of His Rich Friends

Describing how some in his army acted the Persian treasury was looted, Plutarch wrote: “His followers, who were grown rich, and consequently proud, longed to indulge themselves in pleasure and idleness, and were weary of marches and expeditions, and at last went on so far as to censure and speak ill of [213] him. All which at first he bore very patiently, saying, it became a king well to do good to others, and be evil spoken of. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“But when he perceived his favorites grow so luxurious and extravagant in their way of living and expenses, that Hagnon, the Teian, wore silver nails in his shoes, that Leonnatus employed several camels, only to bring him powder out of Egypt to use when he wrestled, and that Philotas had hunting nets a hundred furlongs in length, that more used precious ointment than plain oil when they went to bathe, and that they carried about servants everywhere with them to rub them and wait upon them in their chambers, he reproved them in gentle and reasonable terms, telling them he wondered that they who had been engaged in so many signal battles did not know by experience, that those who labor sleep more sweetly and soundly than those who are labored for, and could fail to see by comparing the Persians’ manner of living with their own, that it was the most abject and slavish condition to be voluptuous, but the most noble and royal to undergo pain and labor. He argued with them further, how it was possible for any one who pretended to be a soldier, either to look well after his horse, or to keep his armor bright and in good order, who thought it much to let his hands be serviceable to what was nearest to him, his own body. “Are you still to learn,” said he, “that the end and perfection of our victories is to avoid the vices and infirmities of those whom we subdue?”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, except the movie poster, IMDB

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024