Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory

HERODOTUS

Herodotos Herodotus (484?-425? B.C.) has been called the Father of History, a compliment initially given to him Cicero. He is given credit for recording information from all over but criticized for using less than reliable sources and sometimes espousing what seems like propaganda. Most of Herodotus's histories were stories he picked up from travelers, merchants and priests. He seems to have known many were exaggerations or unproven claims and he made some effort to pick out what was plausible. Occasionally he ascribed events to myths. Aristotle called him a “legend monger.” [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, April 28, 2008]

Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in The New Yorker, “Herodotus may not always give us the facts, but he unfailingly supplies something that is just as important in the study if what he calls “ta genomena ex anthrupon” or “things that result from human action”: he give us the truth about the way things tend to work as whole, in history, civics, personality, and, of course, psychology.”

Matt Bune of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote:: “Herodotus was a Greek historian in the fifth century B.C. His birth was around 490 B.C. References to certain events in his narratives suggest that he did not die until at least 431 B.C.E, which was the beginning of the Peloponesian War. In his later years, Herodotus traveled extensively throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. There, he visited the Black Sea, Babylon, Phoenicia, and Egypt. He is best known for his work entitled Histories. Because of this, Cicero claimed him to be the Father of History. Histories is the story of the rise of Persian power and the friction between Persia and Greece. The battles that are described are the ones fought at Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis. His story is the historical record of events that happened in his own lifetime. The first Persian War took place just before he was born, while the second happened when he was a child. This gave him the opportunity to question his elders about the events in both wars to get the details he wanted for his story. “Although early Egyptologists regarded his chronicles of Egypt as a valuable source of information, the accuracy of some of Herodotus' writings have been challenged. His eyewitness accounts are thought of as accurate, but the stories told to him are questioned. Some researchers think the people who told Herodotus information could have forgotten parts, or just humored him with an interesting answer having nothing to do with the truth." [Source: Matt Bune Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, a town in Asia Minor that was home to one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, which was finished decades after he left. Halicarnassus was also regarded as a major intellectual center for a time. Herodotus spent some time in Athens and was a friend of Sophocles. He traveled widely and wrote extensively about the places he visited and people and places he heard about. He visited Egypt, southern Italy, Mesopotamia, Persian, the Levent and the Black Sea area. He wrote about the Scythians based on things he heard and pieced together the Persian Wars from oral traditions and things he observed. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Book: “Herodotus” by James Romm is a “lively short study.” “The Way of Herodotus” by Justin Marozzi (De Capo 2009) is an excellent travelog and encounter with Herodotus. “The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) is richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts on everything from designs of ships to ancient measurements but the translation leaves much to be desired. The 1858 translation of “Histories” by George Rawlinson (Everyman Library) captures the “rich Homeric flavor and dense syntax” according to The New Yorker. The 1998 translation of Robin Waterfield (Oxford World Classic) is not bad.

Links to Works by Herodotus

The Histories 440 B.C. MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

The Histories 440 B.C. Parstimes, Chapter length files parstimes.com

The Histories: Vol 1 440 B.C. Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

The Histories: Vol 2 440 B.C. Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

The Histories: Vol 1 440 B.C. in Ancient Greek Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

The Histories: Vol 2 440 B.C. in Ancient Greek Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

The Histories 440 B.C. sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Herodotus” by James Romm Amazon.com is a “lively short study.”

“ The Way of Herodotus” by Justin Marozzi (De Capo 2009) Amazon.com is an excellent travelog and encounter with Herodotus.

“The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) Amazon.com is richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts on everything from designs of ships to ancient measurements but the translation leaves much to be desired.

The 1858 translation of “Histories” by George Rawlinson (Everyman Library) Amazon.com captures the “rich Homeric flavor and dense syntax” according to The New Yorker.

The 1998 translation of “Histories” by Robin Waterfield (Oxford World Classic) Amazon.com; is pretty good.

“The Portable Greek Historians: The Essence of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius” (Portable Library) by M. I. Finley and M. Finley (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Historians” by T. James J. Luce Amazon.com;

“The Essential Greek Historians” by Stanley Burstein (2022) Amazon.com;

“Readings in the Classical Historians” by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“History of the Peloponnesian War” by Thucydides (1834) Amazon.com;

Herodotus’s "Histories"

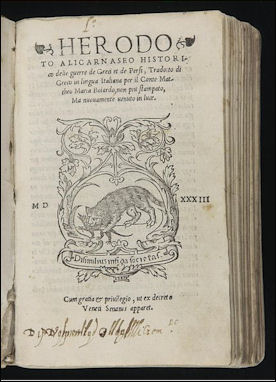

Herodotus's

History of the Persian Wars (1502) Herodotus wrote “Histories” , a nine-volume account of Persian wars between 490 to 479 B.C. Sometimes called “The Persian Wars” or “History”, the work contains frequent and lengthy digressions and seems to leave no detail unturned. Herodotus’s style was lucid but poetic. Some regard him as the first master of prose. Cicero asked “what was sweeter than Herodotus.” A 20th century translator said, “Herodotus’s prose has the flexibility, ease and grace of a man superbly talking.”

Herodotus called his book “Historie” . In his time the word meant “research” or “inquiry” and has come to mean “history” in our sense of the world because of him. The book was so full of details and curious facts it is sometimes considered the first tourist guides and in fact was still the standard travel guide in the 19th century.

The subject of the history of Herodotus is the struggle between the Greeks and the Persians which he brings down to the battle of Mycale in 479 B.C. The work, as we have it, is divided into nine books, named after the nine Muses, but this division is probably due to the Alexandrine grammarians.His information he gathered mainly from oral sources, as he traveled through Asia Minor, down into Egypt, round the Black Sea, and into various parts of Greece and the neighboring countries. The chronological narrative halts from time to time to give opportunity for descriptions of the country, the people, and their customs and previous history; and the political account is constantly varied by rare tales and wonders.[Source: “An Account of Egypt” by Herodotus, Translated By G.C. Macaulay]

There is abundant evidence, too, that Herodotus had a philosophy of history. The unity which marks his work is due not only to the strong Greek national feeling running through it, the feeling that rises to a height in such passages as the descriptions of the battles of Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis, but also to his profound belief in Fate and in Nemesis. To his belief in Fate is due the frequent quoting of oracles and their fulfilment, the frequent references to things foreordained by Providence. The working of Nemesis he finds in the disasters that befall men and nations whose towering prosperity awakens the jealousy of the gods. The final overthrow of the Persians, which forms his main theme, is only one specially conspicuous example of the operation of this force from which human life can never free itself.

Contents of Herodotus’s "Histories"

Herodotus observed a variety of local customs and concluded that men were servants to customs to which they were born. He noted that when Darius offered to pay his Greek subjects to eat the bodies of their fathers instead of burning them as was their custom, they refused no matter how much was offered them. He then offered to give money to Indians, who customarily ate the bodies of their deceased fathers, if they would burn their bodies. They also refused no matter how much was offered them. On the Egyptians he reported "In any home where a cat dies" the residents "shave off their eyebrows" and “sons never take care of their parents if they don’t want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." He also noted “Women urinate standing up, men sitting down.”

His accounts of the natural world are no less entertaining. In the case of vipers and snakes he said the male is killed by the female during copulation but the male is “avenged” by their young who kill the female. In Book 3 he describes how Indian gold is produced by a species of ants—“huge ants, smaller than dogs but larger than foxes.”

Among these descriptions of countries the most fascinating to the modern, as it was to the ancient, reader is his account of the marvels of the land of Egypt. From the priests at Memphis, Heliopolis, and the Egyptian Thebes he learned what he reports of the size of the country, the wonders of the Nile, the ceremonies of their religion, the sacredness of their animals. He tells also of the strange ways of the crocodile and of that marvelous bird, the Phoenix; of dress and funerals and embalming; of the eating of lotos and papyrus; of the pyramids and the great labyrinth; of their kings and queens and courtesans. [Source: “An Account of Egypt” by Herodotus, Translated By G.C. Macaulay]

But, above all, he is the father of story-tellers. "Herodotus is such simple and delightful reading," says Jevons; "he is so unaffected and entertaining, his story flows so naturally and with such ease that we have a difficulty in bearing in mind that, over and above the hard writing which goes to make easy reading there is a perpetual marvel in the work of Herodotus. It is the first artistic work in prose that Greek literature produced. This prose work, which for pure literary merit no subsequent work has surpassed, than which later generations, after using the pen for centuries, have produced no prose more easy or more readable, this was the first of histories and of literary prose. "

Accuracy of Herodotus’s "Histories"

Yet Herodotus is not a mere teller of strange tales. However credulous he may appear to a modern judgment, he takes care to keep separate what he knows by his own observation from what he has inferred and from what he has been told. He is candid about acknowledging ignorance, and when versions differ he gives both. Thus the modern scientific historian, with other means of corroboration, can sometimes learn from Herodotus more than Herodotus himself knew. [Source: “An Account of Egypt” by Herodotus, Translated By G.C. Macaulay]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Perhaps no ancient historian is more respected than Herodotus. However, a recent study has raised questions about his reliability. Herodotus provides the best-known passage on ancient Egyptian mummification techniques, recording how the brains of elites were removed through the nose, and their viscera through an incision in the abdomen. For the lower classes, the less costly route was to flush the corpse’s entrails with a turpentine-like cedar-oil enema. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

But Andrew Wade and Andrew Nelson of the University of Western Ontario examined 150 recent reports on Egyptian mummies and seven CT scans — and found that Herodotus was a bit off. Their findings indicate that abdominal incisions were the most common means of removing the inner organs, and not reserved just for the upper classes. And the researchers identified almost no evidence of the eviscerating oil. Furthermore, only 25 percent of the mummies studied retained the heart in situ — a surprising number, considering the ancient sources emphasize that this organ was almost always left intact.

John Burbery wrote: “Herodotus’ “Histories” claims that dog-sized ants guard certain gold deposits in regions of East Asia. In his 1984 book “The Ants’s Gold: The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas,” ethnologist Michel Peissel uncovered Herodotus’ possible inspiration: mountain-dwelling marmots, who to this day “mine” gold by layering their nests with gold dust. [Source: Timothy John Burbery, Professor of English, Marshall University, The Conversation, January 10, 2022]

Herodotus’s Life

Herodotus (c. 484-425 B.C.), was born at Halicarnassus in Asia Minor, then dependent upon the Persians, in or about the year 484 B.C. Herodotus was thus born a Persian subject, and such he continued until he was thirty or five and thirty years of age. At the lime of his birth Halicarnassus was under the rule of a queen Artemisia (q.v.) The year of her death is unknown; but she left her crown to her son Pisindelis (born about 498 B.C.), who was succeeded upon the throne by his son Lygdamis about the time that Herodotus grew to manhood. The family of Herodotus belonged to the upper rank of the citizens. His father was named Lyxes, and his mother Rhaeo, or Dryo. He had a brother Theodore, and an uncle or cousin Panyasis (q.v.), the epic poet, a personage of so much importance that the tyrant Lygdamis, suspecting him of treasonable projects, put him to death. It is probable that Herodotus shared his relative's political opinions, and either was exiled from Halicarnassus or quitted it voluntarily at the time of his execution. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Of the education of Herodotus no more can be said than that it was thoroughly Greek, and embraced no doubt the three subjects essential to a Greek liberal education-grammar, gymnastic training and music. His studies would be regarded as completed when he attained the age of eighteen, and took rank among the ephebi or eirenes of his native city. In a free Greek state he would at once have begun his duties as a citizen, and found therein sufficient employment for his growing energies. But in a city ruled by a tyrant this outlet was wanting; no political life worthy of the name existed. Herodotus may thus have had his thoughts turned to literature as furnishing a not unsatisfactory career, and may well have been encouraged in his choice by the example of Panyasis, who had already gained a reputation by his writings when Herodotus was still an infant. At any rate it is clear from the extant work of Herodotus that he commenced that extensive course of reading which renders him one of the most instructive as well as one of the most charming of ancient writers. The poetical literature of Greece was already large; the prose literature was more extensive than is generally supposed; yet Herodotus shows an intimate acquaintance with the whole of it. The Iliad and the Odyssey are as familiar to him as Shakespeare to the educated Engliskman. He is acquainted with the poems of the epic cycle, the Cypria, the Epigoni, &c. He quotes or otherwise shows familiarity with the writings of Hesiod, Olen, Musaeus, Bacis, Lysistratus, Archilochus of Paros, Alcaeus, Sappho, Solon, Aesop, Aristeas of Proconnesus, Simonides of Ceos, Phrynichus, Aeschylus and Pindar. He quotes and criticizes Hecataeus, the best of the prose writers who had preceded him, and makes numerous allusions to other authors of the same class.

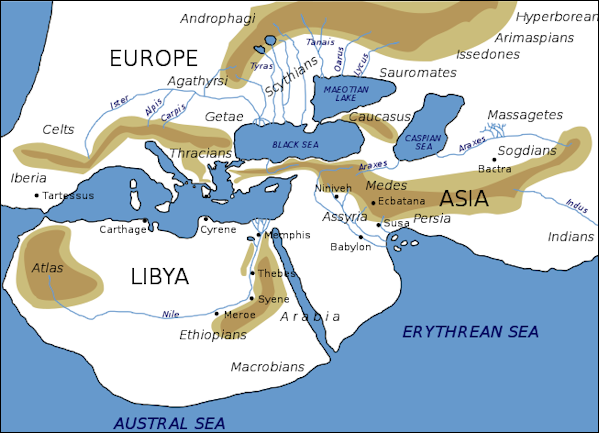

Herodotus's world

“It must not, however, be supposed that he was at any time a mere student. It is probable that from an early age his inquiring disposition led him to engage in travels, both in Greece and in foreign countries. He traversed Asia Minor and European Greece probably more than once; he visited all the most important islands of the Archipelago-Rhodes, Cyprus, Delos, Paros, Thasos, Samothrace, Crete, Samos, Cythera and Aegina. He undertook the long and perilous journey from Sardis to the Persian capital Susa, visited Babylon, Colchis, and the western shores of the Black Sea as far as the estuary of the Dnieper; he travelled in Scythia and in Thrace, visited Zante and Magna Graecia, explored the antiqmties of Tyre, coasted along the shores of Palestine, saw Ga~a, and made a long stay in Egypt. At the most moderate estimate, his travels covered a space of thirtyone degrees of longitude, or 1700 miles, and twentyfour of latitude, or nearly the same distance. At all the more interesting sites he took up his abode for a time; he examined, he inquired, he made measurements, he accumulated materials. Having in his mind the scheme of his great work, he gave ample time to the elaboration of all its parts, and took care to obtain by personal observation a full knowledge of the various countries.

Herodotus Travels

The travels of Herodotus seem to have been chiefly accomplished between his twentieth and his thirtyseventh year (464-447 B.C.). It was probably in his early manhood that as a Persian subject he visited Susa and Babylon, taking advantage of the Persian system of posts which he describes in his fifth book. His residence in Egypt must, on the other hand, have been subsequent to 460 B.C., since he saw the skulls of the Persians slain by Inarus in that year. Skulls are rarely visible on a battlefield for more than two or three seasons after the fight, and we may therefore presume that it was during the reign of Inarus (460-454 B.C.), when the Athenians had great authority in Egypt, that he visited the country, making himself known as a learned Greek, and therefore receiving favour and attention on the part of the Egyptians, who were so much beholden to his countrymen (see ATHENS, CLEON, PERICLES). On his return from Egypt, as he proceeded along the Syrian shore, he seems to have landed at Tyre, and from thence to have gone to Thasos. His Scythian travels are thought to have taken place prior to 450 B.C. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“It is a question of some interest from what centre or centres these various expeditions were made. Up to the time of the execution of Panyasis, which is placed by chronologists in or about the year 457 B.C., there is every reason to believe that Herodotus lived at Halicarnassus. His travels in Asia Minor, in European Greece, and among the islands of the Aegean, probably belong to this period, as also his journey to Susa and Babylon. We are told that when he quitted Halicarnassus on account of the tyranny of Lygdamis, in or about the year 457 B.C., he took up his abode in Samos. That island was an important member of the Athenian confederacy, and in making it his home Herodotus would have put himself under the protection of Athens. The fact that Egypt was then largely under Athenian influence (see CLEON, PERICLES) may have induced him to proceed, in 457 or 456 B.C., to that country. The stories that he had heard in Egypt of Sesostris may then have stimulated him to make voyages from Samos to Colchis, Scythia and Thrace. He was thus acquainted with almost all the regions which were to be the scene of his projected history.

Herodotus world map

Herodotus Returns Home

After Herodotus had resided for some seven or eight years in Samos, events occurred in his native city which induced him to return thither. The tyranny of Lygdamis had gone from bad to worse, and at last he was expelled. According to Suidas, Herodotus was himself an actor, and indeed the chief actor, in the rebellion against him; but no other author confirms this statement, which is intrinsically improbable. It is certain, however that Halicarnassus became henceforward a voluntary member of the Athenian confederacy. Herodotus would now naturally return to his native city, and enter upon the enjoyment of those rights of free citizenship on which every Greek set a high value. He would also, if he had by this time composed his history, or any considerable portion of it, begin to make it known by recitation among his friends. There is reason to believe that these first attempts were not received with much favour, and that it was in chagrin at his failure that he precipitately withdrew from his native town, and sought a refuge in Greece proper (about 447 B.C.). We learn that Athens was the place to which he went, and that he appealed from the verdict of his countrymen to Athenian taste and judgment. His work won such approval that in the year 445 B.C., on the proposition of a certain Anytus, he was voted a sum of ten talents (£2400) by decree of the people. At one of the recitations, it was said, the future historian Thucydides was present with his father, Olorus, and was so moved that he burst into tears, whereupon Herodotus remarked to the father-"Olorus, your son has a natural enthusiasm for letters." [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Athens was at this time the centre of intellectual life, and could boast an almost unique galaxy of talent-Pericles, Thucydides the son of Melesias, Aspasia, Antiphon, the musician Damon, Pheidias, Protagoras, Zeno, Cratinus, Crates, Euripides and Sophocles. Accepted into this brilliant society, on familiar terms with all probably, as he certainly was with Olorus, Thucydides and Sophocles, he must have been tempted, like many another foreigner, to make Athens his permanent home. It is to his credit that he did not yield to this temptation. At Athens he must have been a dilettante, an idler, without political rights or duties. As such he would have soon ceased to be respected in a society where literature was not recognized as a separate profession, where a Socrates served in the infantry, a Sophocles commanded fleets, a Thucydides was general of an army, and an Antiphon was for a time at the head of the state. Men were not men according to Greek notions unless they were citizens; and Herodotus, aware of this, probably sharing in the feeling, was anxious, having lost his political status at Halicarnassus, to obtain such status elsewhere. At Athens the franchise, jealously guarded at this period, was not to be attained without great expense and difficulty. Accordingly, in the spring of the following year he sailed from Athens with the colonists who went out to found the colony of Thurii (see PERICLES), and became a citizen of the new town.

“From this point of his career, when he had reached the age of forty, we lose sight of him almost wholly. He seems to have made but few journeys, one to Crotona, one to Metapontum, and one to Athens (about 430 B.C.) being all that his work indicates. No doubt he was employed mainly, as Pliny testifies, in retouching and elaborating his general history. He may also have composed at Thurii that special work on the history of Assyria to which he twice refers in his first book, and which is quoted by Aristotle. It has been supposed by many that he lived to a great age, and argued that "the nevertobemistaken fundamental tone of his performance is the quiet talkativeness of a highly cultivated, tolerant, intelligent, old man" (Dahlmann). But the indications derived from the later touches added to his work, which form the sole evidence on the subject, would rather lead to the conclusion that his life was not very prolonged. There is nothing in the nine books which may not have been written as early as 430 B.C.; there is no touch which, even probably, points to a later date than 424 B.C. As the author was evidently engaged in polishing his work to the last, and even promises touches which he does not give, we may assume that he did not much outlive the date last mentioned, or in other words, that he died at about the age of sixty. The predominant voice of antiquity tells us that he died at Thurii, where his tomb was shown in later ages.

Accounts from Herodotus’s History

The Persian Wars take up about a third of “History” — from the middle of Book 5 to the end of Book 9. The first four and half books proceed at a leisurely pace, with a lot of digressions, explaining the rise of the Persian Empire and tells readers everything they would ever want to know about Persia. See Persians Wars, History

Herodotus was from Halicarnassus, home of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World

Herodotus devoted nearly all of Book 2 of “History to describing the achievements and the curiosities of the Egyptians. In Book 3 he describes the Persians enc ounter with the Ethiopians, which he describes as the tallest and most beautiful people in the world;. In Book 4 he describes the Scythians, ancient Mongol-like Horsemen that lived at the same time as the Greeks, and their maddening tactic and packing up their camps and leaving before they are attacked.

Herodotus wrote extensively about the Scythians. He described them as savage warriors who committed many atrocities. Some think that Herodotus gave the Scythians an unjustified, prejudiced bad rap and in all probability they committed no more atrocities than the Romans, Persians, Egyptians or even the Greeks themselves. It is not clear how much was based on first hand observation or second hand accounts but the latter seems most likely. It is also not clear how extensively Herodotus traveled in the Black Sea-Dnieper River heartland of the Scythians On one journey around 450 B.C. he probably reached Olbia, 40 miles west of the Dnieper River.

Herodotus begins “Histories” with his account if Croesus and calls him “the first barbarian known who subjugated and demanded tribute from Hellenes.” The tale offers an introduction to a theme that would pervade the nine volumes of “Histories” — don’t overstep your bounds. Blinded by his success Croesus arrogantly misinterpreted a pronouncement by the Oracle of Delphi: “If you attack Persia you will destroy a great empire.” Croesus thought the oracle was referring to the Persians but she was in fact referring to his own. Sardis was sacked by the Persians. According to Herodotus, Croesus asked Cyrus, “What is it that all these men of yours are so intent upon doing.” Cyrus replied: “They are plundering your city and carrying off your treasures.” Croesus then corrected him: “Not my city or my treasures. Nothing there any longer belongs to me. It is you they are robbing.”

Why Did Herodotus Write Histories?

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “The History.-In estimating the great work of Herodotus, and his genius as its author, it is above all things necessary to conceive aright what that work was intended to be. It has been called "a universal history," "a history of the wars between the Greeks and the barbarians," and "a history of the struggle between Greece and Persia." But these titles are all of them too comprehensive. Herodotus, who omits wholly the histories of Phoenicia, Carthage and Etruria, three of the most important among the states existing in his day, cannot have intended to compose a "universal history," the very idea of which belongs to a later age. He speaks in places as if his object was to record the wars between the Greeks and the barbarians; but as he omits the Trojan war, in which he fully believes, the expedition of the Teucrians and Mysians against Thrace and Thessaly, the wars connected with the Ionian colonization of Asia Minor and others, it is evident that he does not really aim at embracing in his narrative all the wars between Greeks and barbarians with which he was acquainted. Nor does it even seem to have been his object to give an account of the entire struggle between Greece and Persia. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“That struggle was not terminated by the battle of Mycale and the capture of Sestos in 479 B.C. It continued for thirty years longer, to the peace of Callias (but see CALLIAS and CIMON). The fact that Herodotus ends his history where he does shows distinctly that his intention was, not to give an account of the entire long contest between the two countries, but to write the history of a particular war- the great Persian war of invasion. His aim was as definite as that of Thucydides, or Schiller, or Napier or any other writer who has made his subject a particular war; only he determined to treat it in a certain way. Every partial history requires an "introduction", Herodotus, untrammelled by examples, resolved to give his history a magnificent introduction. Thucydides is content with a single introductory book, forming little more than oneeighth of his work; Herodotus has six such books forming twothirds of the entire composition.

“By this arrangement he is enabled to treat his subject in the grand way, which is so characteristic of him. Making it his main object in his "introduction" to set before his readers the previous history of the two nations who were the actors in the great war, he is able in tracing their history to bring into his narrative some account of almost all the nations of the known world, and has room to expatiate freely upon their geography antiquities, manners and customs and the like, thus giving his work a "universal" character, and securing for it, without trenching upon unity, that variety, richness and fulness which are a principal charm of the best historics, and of none more than his. In tracing the growth of Persia from a petty subject kingdom to a vast dominant empire, he has occasion to set out the histories of Lydia, Media, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Scythia, Thrace, and to describe the countries and the peoples inhabiting them, their natural productions, climate, geographical position, monuments, &c.; while, in noting the contemporaneous changes in Greece, he is led to tell of the various migrations of the Greek race, their colonies, commerce, progress in the arts, revolutions, internal struggles, wars with one another, legislation, religious tenets and the like. The greatest variety of episodical matter is thus introduced; but the propriety of the occasion and the mode of introduction are such that no complaint can be made; the episodes never entangle, encumber or even unpleasantly interrupt the main narrative.

Herodotus as a Writer and Historian

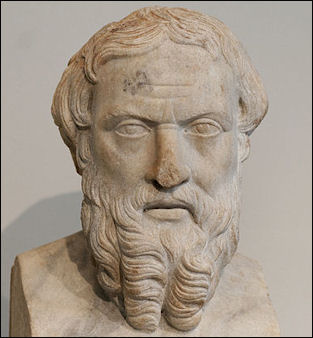

Herodotus at the Louvre

It has been questioned, both in ancient and in modern times, whether the history of Herodotus possesses the essential requisite of trustworthiness. Several ancient writers accuse him of intentional untruthfulness. Moderns generally acquit him of this charge; but his severer critics still urge that, from the inherent defects of his character, his credulity, his love of effect and his loose and inaccurate habits of thought, he was unfitted for the historian's office, and has produced a work of but small historical value. Perhaps it may be sufficient to remark that the defects in question certainly 'exist, and detract to some extent from the authority of the work, more especially of those parts of it which deal with remoter periods, and were taken by Herodotus on trust from his informants, but that they only slightly affect the portions which treat of later times and form the special subject of his history. In confirmation of this view, it may be noted that the authority of Herodotus for the circumstances of the great Persian war, and for all local and other details which come under his immediate notice, is accepted by even the most skeptical of modern historians, and forms the basis of their narratives. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

Among the merits of Herodotus as an historian, the most prominent are the diligence with which he collected his materials, the candor and impartiality with which he has placed his facts before the reader, the absence of party bias and unduc national vanity, and the breadth of his conception of the historian's office. On the other hand, he has no claim to rank as a critical historian; he has no conception of the philosophy of history, no insight into the real causes that underlie political changes, no power of penetrating below the surface or even of grasping the real interconnection of the events which he describes. He belongs distinctly to the romantic school; his forte is vivid and picturesque description, the lively presentation of scenes and actions, characters and states of society, not the subtle analysis of motives, the power of detecting the undercurrents or the generalizing faculty.

“But it is as a writer. that the merits of Herodotus are most conspicuous. "O that I were in a condition," says Lucian, "to resemble Herodotus, if only in some measure! I by no means say in all his gifts, but only in some single point; as, for instance, the beauty of his language, or its harmony, or the natural and peculiar grace of the Ionic dialect, or his fullness of thought, or by whatever name those thousand beauties are called which to the despair of his imitator are united in him." Cicero calls his style "copious and polished," Quintilian, "sweet, pure and flowing"; Longinus says he was "the most Homeric of historians"; Dionysius, his countryman, prefers him to Thucydides, and regards him as combining in an extraordinary degree the excellences of sublimity, beauty and the true historical method of composition. Modern writers are almost equally complimentary. "The style of Herodotus," says one, "is universally allowed to be remarkable for its harmony and sweetness." "The charm of his style," argues another, "has so dazzled men as to make them blind to his defects." Various attempts have been made to analyse the charm which is so universally felt; but it may be doubted whether any of them are very successful. All, however, seem to agree that among the qualities for which the style of Herodotus is to be admired are simplicity, freshness, naturalness and harmony of rhythm. Master of a form of language peculiarly sweet and euphonical, and possessed of a delicate ear which instinctively suggested the most musical arrangement possible, he gives his sentences, without art or effort, the most agreeable flow, is never abrupt, never too diffuse, much less prolix or wearisome, and being himself simple, fresh, naif (if we may use the word), honest and somewhat quaint, he delights us by combining with this melody of sound simple, clear and fresh thoughts, perspicuously expressed, often accompanied by happy turns of phrase, and always manifestly the spontaneous growth of his own fresh and unsophisticated mind. Reminding us in some respects of the quaint medieval writers, Froissart and Philippe de Comines, he greatly excels them, at once in the beauty of his language and the art with which he has combined his heterogeneous materials into a single perfect harmonious whole. See also GREECE, section History, Authorities.

Herodotus’s Insights on Africa and the Sun

Gareth Dorrian and Ian Whittaker wrote: The Histories by Herodotus (484BC to 425BC) offers a remarkable window into the world as it was known to the ancient Greeks in the mid fifth century B.C.. Almost as interesting as what they knew, however, is what they did not know. This sets the baseline for the remarkable advances in their understanding over the next few centuries — simply relying on what they could observe with their own eyes. [Source: Gareth Dorrian, Post Doctoral Research Fellow in Space Science, University of Birmingham and Ian Whittaker, Lecturer in Physics, Nottingham Trent University, The Conversation, April 24, 2020]

“Herodotus claimed that Africa was surrounded almost entirely by sea. How did he know this? He recounts the story of Phoenician sailors who were dispatched by King Neco II of Egypt (about 600BC), to sail around continental Africa, in a clockwise fashion, starting in the Red Sea. This story, if true, recounts the earliest known circumnavigation of Africa, but also contains an interesting insight into the astronomical knowledge of the ancient world.

“The voyage took several years. Having rounded the southern tip of Africa, and following a westerly course, the sailors observed the Sun as being on their right hand side, above the northern horizon. This observation simply did not make sense at the time because they didn’t yet know that the Earth has a spherical shape, and that there is a southern hemisphere.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024