Home | Category: First Modern Human Life / Life and Culture in Prehistoric Europe

DOG HISTORY

Shar Pei, one of the

oldest dog breeds All dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) descended from the gray wolf, the largest member of the Canidae family. Gray wolves are native to the northern hemisphere continental areas, including North America and Eurasia. Dogs and wolves are still capable of interbreeding.

Dogs and canids (wolf-like and dog-like animals) evolved from hesperocyons, predators that looked somewhat like jackals and lived 37 million years ago in North America. They had distinctive pairs of shearing teeth and ran down prey. Some regard the first canid as “Prophesperocyon wilsoni”, a creature that lived in what is now southwestern Texas about 40 million years and had teeth that were evolved towards a more shearing bite. It ancestors had more elongated limbs and toes packed close together which facilitated running faster. As their prey began runner faster they too adapted by running faster themselves They also developed the ability to crack and eat bones, which suggests that regularly scavenged carcasses.

Early canids reached Europe about 7 million years ago. The Eucyon, a species that arose 7 million years and moved west 6 million to 4 million years ago, gave birth to most modern canids, including wolves, coyotes, jackals and dogs.

Dogs are believed to have been the first animals to be domesticated by ancient humans. Most archaeologists believe that dogs were first domesticated about 14,000 years ago. This was before the development of agriculture and permanent human settlements. There are currently about 400 million dogs in the world and 400,000 wolves. [Source: Xiaoming Wang and Richard Tedford, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008; Angus Phillips, National Geographic, January 2002]

Dogs have played an important role in human culture for thousands of years.The archaeological record of dogs dates back to 31,000 years ago to a Great-Dane-like species found in Belgium. There are archaeological records of dogs going back 26,000 years in the Czech Republic and 15,000 years in Siberia, said Robert Wayne, a professor of evolutionary biology at UCLA and a dog evolution expert. But canine records in the New World aren't as detailed or go back nearly as far.The first Middle East dogs appeared 12,000 to 13,000 years ago. Unlike domesticated livestock, which has been closely related to agriculture, dogs have had closer links to hunters and gatherers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DOGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND INTELLIGENCE europe.factsanddetails.com

DOMESTICATION OF DOGS: THEORIES, EVIDENCE, WHY AND HOW europe.factsanddetails.com

WHEN AND WHERE DOGS WERE FIRST DOMESTICATED europe.factsanddetails.com

WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, SPECIES, NUMBERS factsanddetails.com

CANIDS, CANINES AND CANIS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WOLF BEHAVIOR: PACKS, HIERARCHIES, MATING, PUPS factsanddetails.com;

GRAY WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WOLF FOOD: DIET, HUNTING: PREY, TACTICS, FEEDING HABITS factsanddetails.com;

WOLVES AND HUMANS: STORIES, LIVESTOCK, REWILDING factsanddetails.com

WOLF ATTACKS ON HUMANS: WHERE, WHY, WHEN, HOW factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Dog's History of the World: Canines and the Domestication of Humans”

by Laura Hobgood-Oster (2014) Amazon.com;

“Dogs: Archaeology beyond Domestication” by Brandi Bethke and Amanda Burtt Amazon.com;

“The Dog: A Natural History” by Ádám Miklósi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Oldest Companions: The Story of the First Dogs” by Pat Shipman (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction”

by Pat Shipman Amazon.com;

“Dogs: A New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution” (2002) by Raymond Coppinger, Lorna Coppinger Amazon.com;

“First Dog on Earth, How It All Began | An Odyssey of Survival and Trust (Novel)

by Irv Weinberg (2021) Amazon.com;

“Domesticated: Evolution in a Man-Made World” by Richard C. Francis Amazon.com;

“The Process of Animal Domestication” by Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Dog Breed Book, New Edition” by DK (2020) Amazon.com;

“The New Complete Dog Book” by the American Kennel Club (2017)

(2017) Amazon.com;

Ancestors of Dogs

Saluki, the world's oldest

dog breed Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford wrote in “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History”: “The downfall of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago gave mammals an incredible opening, and they ran for it, rapidly becoming the dominant land vertebrates. Among those to emerge were the earliest carnivorans (members of the order Carnivora), whose living representatives include the cats and closely allied families, such as hyenas and mongooses, as well as dogs and closely allied families, such as bears, weasels, and seals. As their name implies, most carnivorans eat meat, and even those that aren’t carnivorous—such as the giant panda—can be recognized. [Source: from “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History,” by Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford, 2008 Columbia University Press, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008 ]

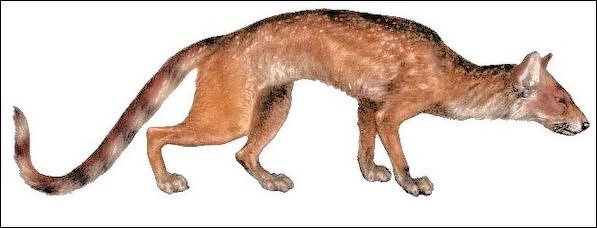

“A young adult Eucyon davisi, about the size of a living coyote, approaches one of its parents in a submissive attitude. The large social groupings in several species of the subfamily Caninae may have arisen when such youngsters remained in their parents’ territory and helped raise pups. The genus Eucyon lived in North America from about 9 million to 5 million years ago. by the last upper premolar and first lower molar on each side of the mouth. Those teeth are specially adapted for shearing, and are known as carnassials. Only in some species, such as seals and sea lions, have the carnassials evolved into simpler forms.

“Back when mammals got their big break—during the Paleocene epoch, which lasted ten million years—conditions around the globe were warm and humid. And the epoch that followed, the Eocene, was marked by a warming trend so great that even the polar regions were quite hospitable to life. Surging into prominence, flowering plants diversified and created lush forests all over the Earth. In North America, where tree canopies sheltered a growing number of primates and other forest-dwelling mammals, the earliest carnivorans arose. From there they spread to Eurasia, over land bridges that then existed to Europe or near the present-day Bering Strait. Mostly the size of small foxes, or smaller, the carnivorans were adapted to life in and around trees, probably preying on invertebrates and small vertebrates. They lived in the shadow of the generally much larger hyaenodonts, a group of mammalian predators that had come on the scene earlier but which later became extinct.”

Canids, Canines and Canis

Canidae is a biological family of caniform carnivorans ("dog-like" carnivores). It constitutes a clade (group of organisms composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants) Members of this family are called canids. The family includes three subfamilies: Caninae, and extinct Borophaginae and Hesperocyoninae. Caninae are known as canines,and include domestic dogs, wolves, coyotes, raccoon dogs, foxes, jackals, African wild dogs and other species. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Canidae family is comprised of 13 genera and 37 species. Canids are widely distributed around the globe. They occur on all continents except Antarctica and are only member of the Order Carnivora that found in Australia (we’re talking about dingoes, introduced by humans during prehistoric times). Canidae fossils have been dated to the to the Oligocene Period (33 million to 23.9 million years ago) and Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), which makes them among the oldest extant groups of carnivores. Canids are probably an early offshoot of the caniform lineage (which includes mustelids (weasels),procyonids (raccoons and their relatives), ursids (bears), phocids and otariids (seals), and odobenids (walruses).[Source: Bridget Fahey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Eucyon davisi

Canis encompasses "dog like" canids. It is a diverse genera encompassing seven species of canids which include jackals, wolves, coyotes, and domesticated dogs. Canis means "dog" in Latin, "canine tooth" is also derived from Canis and refers due to the long fang-like teeth that all canids possess. Previously the Canis included foxes but they were removed and separated into their own Vulpes genera. African wild dogs are canids but not canis. They are classified into the genus Lycaon and are the only surviving member of this genus.[Source: Lydia Oliver, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

See Separate Article: CANIDS, CANINES AND CANIS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

First Canids

Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford wrote in “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History”:“When did the carnivorans split into their catlike and doglike divisions? No one knows exactly; it may have been 50 million years ago or even earlier. By 40 million years ago, however, the first clearly identifiable member of the dog family itself, the Canidae, had arisen in what is now southwestern Texas. Named Prohesperocyon wilsoni, the fossil species bears a combination of features that together mark it as a canid. Fittingly enough, these include features of the teeth—including the loss of the upper third molars, part of a general trend toward a more shearing bite—along with a characteristically enlarged bony bulla, the rounded covering over the middle ear. Based on what we know about its descendants, Prohesperocyon likely had slightly more elongated limbs than its predecessors, along with toes that were parallel and closely touching, rather than splayed, as in bears. [Source: from “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History,” by Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford, 2008 Columbia University Press, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008 ]

“The dog family thrived on such limb adaptations, which helped support a cursorial, or running, lifestyle in response to a changing environment. And none too soon, for the subsequent epoch, the Oligocene, between 34 million and 23 million years ago, started a long trend of climatic deterioration. Ice sheets appeared on the Antarctic continent for the first time, while in mid-latitude North America, conditions became progressively dryer and seasonal variations more pronounced. The lush, moist forests of the late Eocene gave way to dry woodlands and then to wooded grasslands, with large areas of open grassland developing by 30 million years ago. Mammalian herbivores began to evolve teeth adapted to eating grass (so-called high-crowned teeth, which continue to erupt as the chewing surfaces are worn down). For both predators and prey, the ability to run and survive in an open, exposed landscape became crucial. To a large extent, the history of the dog family is a story of how a group of cursorial predators evolved, through speed and intelligence, to catch changing prey in a changing landscape.

Hesperocyoninae

“Soon after its beginnings 40 million years ago, the dog family (Canidae) diverged into three main subfamilies, each of which dominated in turn. The figure illustrates major branching points, with the width of each lineage representing its species diversity through time. All three subfamilies coexisted for a long time. Two (the Hesperocyoninae and the Borophaginae) became extinct in turn, but the Caninae, with thirty-six species, is going strong. (Portraits of the selected species shown are not drawn to the same scale.)

“The canids are one of three modern families of carnivorans notable for including top predators, species capable of hunting down prey several times their own size. The other two are the cat family (the felids) and the hyena family (the hyaenids). On land, at least, there appears to be a body-size threshold of around forty-five pounds beyond which a mammalian predator must begin to tackle larger prey in order to get enough energy. Chris Carbone, a senior research fellow in biodiversity and macroecology, and colleagues at the Institute of Zoology, the research division of the Zoological Society of London, have suggested that small predators can sustain themselves on invertebrates and small vertebrates because of their low absolute energy requirements.

“In 1871, pioneer vertebrate paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope formulated the principle that in animals, small body sizes tend to evolve into large body sizes. With the help of our colleagues Blaire Van Valkenburgh, a functional morphologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, and John Damuth, a biostatistician at the University of California, Santa Barbara, we have examined the canid fossil record with that idea in mind. We have concluded that, indeed, larger and larger species have repeatedly evolved in many lineages. Consequently, many species have independently passed the threshold where they needed to take down large prey. Features of their jaws and teeth show that the larger canid species have also tended to become hypercarnivorous, that is, more purely meat-eating.

“The cat family and the hyena family similarly evolved hypercarnivorous top predators. (One might think the bear family, the ursids, should be added to this list, but only the polar bear is hypercarnivorous, and it is a rather atypical member of the family. Most bears are omnivores.) It’s only a slight oversimplification to say that felids almost invariably approach their prey in stealth and try to pounce on it in surprise attacks. Modern canids, by contrast, have a decidedly different tactic, one suited to their ancestors’ lifestyle on the open plains. In that setting, surprise attack is seldom achieved; it is less important to subdue the prey in the shortest possible time than to outrun and exhaust the quarry. Lacking retractable claws, a powerful weapon for most felids, canids rely more on social hunting when confronting large prey—using sheer numbers and coordinated hunting strategies rather than sophisticated weaponry to overwhelm them.

The latest Miocene Eucyon dispersal (11.6 to 5.3 million years ago): is from Early Hemphillian localities in the western North America (●). The genus quickly expands its record to east in the central and south eastern North America, where it is a common element in late Hemphillian local faunas (□). The late Miocene (MN 12-13 in the European mammal biochronology; ○ locations correspond to time of transcontinental dispersal of the genus, across the Beringia, towards Asia, Europe, and Africa. The figure is completed by a reconstructed scene of a group of adult Eucyon moving eastward in a late Miocene Central Asia grassland scenario. The artistic scene aims to ideally represent the dispersal of the genus Eucyon from North America to the Old World during the latest Miocene.

“Hyaenids are more closely related to cats, yet they more strongly resemble canids, both behaviorally and anatomically. They kill their prey by consuming them alive, rather than by delivering a killing bite on the neck as felids do. They too are persistent pursuers rather than stalkers that ambush prey, and they tend to be highly social hunters. The similarities are a good example of convergent evolution, an understandable outcome when one realizes that for much of their evolutionary history, the two groups were not direct competitors but were facing similarly open environments. Canids were at first confined to North America, whereas hyaenids arose in Eurasia.”

Many Canid Species Emerge

Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford wrote in “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History”: “When did canids become so diverse? From Hesperocyon, a descendant of Prohesperocyon, the family experienced its initial radiation in the early Oligocene, about 34 million years ago, splitting into three major subfamilies: the Hesperocyoninae and the Borophaginae (both extinct lineages known only from fossils), and the Caninae, whose descendants survive today. But it is at first only among the hesperocyonines that we see some really dominant dogs, capable of hunting prey larger than themselves. They were the size of small wolves and equipped with teeth specialized for ripping into raw meat, comparable to those of modern African hunting dogs. The early borophagines, on the other hand, were all smaller and tended toward less predatory lifestyles. And biding its time was the Caninae subfamily, comprising only a few inconspicuous species (we’ll avoid calling them “canines,” a term that is usually used in a narrower sense). [Source: from “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History,” by Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford, 2008 Columbia University Press, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008 ]

“Altogether, by about 30 million to 28 million years ago, twenty-five species of canids roamed western North America, a peak of diversity within a continent unequaled before or since by any single family of carnivoran. The dog family was making its mark. Meanwhile, the hyaenodonts and other archaic predators had begun to decline, and they were eventually overtaken by the successful carnivorans.

“North American herbivores, the potential prey for canids, steadily diversified during the first half of the following epoch, the Miocene, which lasted from 23 million to 5 million years ago. That was thanks not only to evolution but also to immigration of Eurasian native species via land bridges. The herbivores reached an all-time peak of diversity around 15 million years ago, and perhaps not coincidentally, canids experienced a second peak of diversity (some twenty species) at the same time. But now mostly the borophagines were the ones to flourish. The hesperocyonines were on the verge of extinction, while the Caninae continued to keep a low profile.

The early and mid-Pliocene Eucyon distribution (5.3 to 3.3 million years ago): A, during early and mid-Pliocene times (◇) the genus Eucyon had a wide distribution across Eurasia. The very late record of the genus (○, late Pliocene/middle Villafranchian) seems to be limited to central Asia and to the more arid areas of eastern Eurasia (Turkey, North Africa); B, the typical Pliocene species from Europe E. adoxus from St-Estève (near Perpignan, France; MN 15), cast of skull (approximate length 18 cm) and mandible (reversed) from Hsia Kou (Yushe basin, China; Pliocene),cast of skull (approximate length 15 cm) from Chao Chuang (Yushe basin, China; Pliocene), cast of skull (reversed) and mandibular ramus (approximate length of mandibular ramus 10 cm).

“Among the factors driving canid evolution was the increasing speed of the grazing herbivores, which in turn was a response to being preyed upon in open habitats. The well-known illustration of this process is how members of the horse family essentially came to run on the tips of their toes, evolving longer toe bones and eventually losing their lateral digits. Even though canids were getting faster, they also had to adjust to competition from new carnivoran immigrants, including members of the cat family; false saber-tooth cats (which were catlike but not true felids); large mustelids; and giant bear dogs (family Amphicyonidae). Bone-cracking became a specialty of the new borophagine species that arose at the time, suggesting that they regularly scavenged carcasses—a kind of resource that is easier to locate in a more open environment. The ability to consume bones may have arisen as a byproduct of group feeding among social predators, in which individuals, trying to consume as much food as quickly as possible, ate bone (or swallowed meat plus bones indiscriminately).

“The Caninae lineage, present from the early Oligocene, finally made its big move during the late Miocene, as the open grasslands continued to expand. One distinctive feature of the subfamily, which had slender, elongated limbs, is that the front and hind big toes became progressively smaller, and ceased to be functional. This cursorial feature, not found in the other two canid subfamilies, became an advantage when the landscape opened up. By the late Miocene, early precursors of the modern “true” foxes (tribe Vulpini) had emerged, as well as a genus, Eucyon, that was ancestral to the tribe Canini. The latter group comprises the “canines” in the narrow sense of the term, and includes dogs, wolves, coyotes, jackals, certain foxes, and other species.”

Canids Migrate Around the World

Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford wrote in “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History”: “A key development in Caninae history was the spread of the subfamily out of North America, beginning about 7 million years ago, when some groups crossed the Bering land bridge into Asia. With the exception of a single species in the middle Miocene of China, hesperocyonines never escaped the dog family cradle, nor did any borophagines. Records of the Caninae appeared in Europe first, and almost immediately thereafter in Asia and Africa. The first member of the genus Canis—to which the gray wolf, coyotes, jackals, and the domesticated dog belong—loped onto the scene about 6 million years ago. [Source: from “Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History,” by Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford, 2008 Columbia University Press, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008,]

Borophaginae

“During the subsequent epoch, the Pliocene (5.3 million to 1.8 million years ago), a further opportunity opened up for the Caninae. About 3 million years ago, the Panamanian Isthmus formed, linking North and South America. Carnivorans that arrived in South America generally trumped the native predators, and the Caninae were part of that success story, radiating explosively out of a few lineages in Central America and southern North America. Members of the subfamily constitute the largest group of carnivoran predators in South America today. Indeed, with eleven species, South America is home to almost one-third of the entire canid diversity on the planet.

“Just as the intercontinental flux led to a new peak of diversity among the canids—one that continues through the Pleistocene epoch and down to the present time—so, too, did it influence the array of prey. Ancestral horse species, which had lost their two outer digits but retained three, were eclipsed in North America by single-digit horses. By Pliocene to early Pleistocene times, the modern horse genus, Equus, had spread to Eurasia and South America, along with members of the camel family (mostly llamas and their extinct relatives), which, like canids, had been confined to North America during much of their existence. While the Caninae subfamily thrived, however, borophagines dwindled to one or two species of highly specialized bone-cracking dogs, which became extinct by the end of the Pliocene.

“The third canid expansion brought dogs into contact with hyaenids, which, with one brief exception during the Pliocene, had never expanded into North America. By the Pliocene, however, the competitive landscape had changed significantly for both families, and their members weren’t fighting for the same fare. The foxes and jackal-like dogs that arrived in the Old World were much smaller than most hyaenids, which by now were all large, bone-cracking animals.

Caninae

“If we look around today at the major terrestrial carnivoran families—canids, felids, ursids, mustelids, and others—we see that each has a balanced spectrum of small and large species, but not the hyaenids. Apart from the aardwolf, which is a highly specialized termite-eater, there are only three living species of hyenas, all large carnivores. In the major carnivoran families, if the large-size species become extinct in the future, smaller forms could evolve to replace them. But if the large hyenas one day become extinct, their great evolutionary lineage will end.

“Climate change kicked into high gear during the Pleistocene epoch, whose alternating cold, dry ice ages and warm, humid intervals was a tumultuous time for all animal and plant evolution. Many mammal species on the northern continents (North America and Eurasia), particularly herbivores, attained giant sizes as an adaptation to extreme cold. Large body size helped not only to conserve heat, but also to store more fat to cope with winter weather. Woolly mammoths, giant deer, and woolly rhinos roamed Eurasia, and the woolly mammoth, mastodon, giant ground sloth, large saber-tooth cat, and dire wolf reigned supreme in North America. Most such megafauna became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, about 10,000 years ago. But the gray wolf, Canis lupus, is one of the few exceptions, and remains one of the most successful large canids in the world.

“From about the beginning of the Pleistocene the genus Canis has had a continuous presence in Eurasia, along with various species of fox and raccoon dog. Gray wolves are present beginning about 1 million years ago. Early humans—Homo erectus, H. neanderthalensis, and H. sapiens—must have competed with some larger species of canids, because they shared a broadly similar hunting (and scavenging) lifestyle. By the end of the Pleistocene, the inevitable close encounters between modern humans and wolves—in the Middle East or Europe, or possibly China—resulted in the first domestication of a canid. If one counts the domestic dog as a highly specialized adaptation for cohabiting with humans, then canids have achieved ultimate success in occupying nearly every corner of the world—in all sizes, shapes, and speeds.”

7.5 Million-Year-Old Bear Dog

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: With jaws equipped to tear the flesh from the bones of their prey, extinct carnivores known as "bear dogs" were powerful predators that prowled Asia, southern Africa, Europe and North America more than 7.5 million years ago. In 2002, researchers announced they had unearthed the jawbone of one of these extinct carnivores in the Pyrenees mountain range in Europe, shedding light on just how deadly bear dogs were, and confirming how widely they were distributed around the world. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, July 9, 2022]

Bear dogs, an extinct group of land-based carnivores in the family Amphicyonidae, are not in the bear family (Ursidae) or the dog family (Canidae), though they possess physical features similar to animals from both groups. The fossilized lower jawbone represents a new species and perhaps a new genus of bear dog. The researchers named the genus, Tartarocyon, which is a nod to Tartaro, a menacing one-eyed giant who, according to Basque mythology, resided in Béarn during the late 8th century B.C., in the southwestern region of France, where the fossil was discovered.

Measuring approximately 20 centimeters (8 inches) long, the mandible was embedded in a fossil-rich area of marine sediment studded with ancient shells. The jawbone's most "striking" feature is its teeth, Floréal Solé, a paleontologist with the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Science and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email. A fourth lower premolar that had never been seen in the group before indicated to the researchers that the fossil belonged to a new genus and species, and hinted that it was likely a “bone-crushing mesocarnivore," the scientists reported in a new study.

Bear dogs were heavy-bodied and flat-footed walkers like bears, but they had relatively long legs and snouts like many dogs do. They lived during the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago) and the animals varied widely in size, weighing from 9 to 320 kilograms (20 to 705 pounds). Researchers estimate that Tartarocyon was one of the bigger species, weighing approximately 200 kilograms (441 pounds).

Dog Domestication

Dogs are believed to have been the first animals to be domesticated by ancient humans. Most archaeologists believe that dogs were first domesticated about 14,000 years ago. This was before the development of agriculture and permanent human settlements. There are currently about 400 million dogs in the world and 400,000 wolves. [Source: Xiaoming Wang and Richard Tedford, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008; Angus Phillips, National Geographic, January 2002]

Humans and wolves or proto dogs came together perhaps because they traveled in groups of about the size, inhabited the same areas and hunted the same prey and were able to help each other: with their sensitive noses dogs were good at locating prey, with their tools and weapons and skills early humans were good at killing large animals. It seems likely that wolves or proto dogs lurked around early human camps.

Offering a scenario of how dogs and humans came together Rudyard Kipling wrote in "Just So Stories" in 1912: "The Woman picked up a roasted mutton-bone and threw it to Wild Dog, and said, “Wild Dog,” and said, 'Wild Thing out of the Wild Woods, taste and try.' Wild Dog gnawed the bone, and it was more delicious than anything he had ever tasted, and he said, 'O my Enemy and Wife of my Enemy, give me another.'..,"The Woman said, 'Wild Thing out of the Wild Woods, help my Man to hunt through the day and guard this cave at night, and I will give you as many roast bones and you need."

See Separate Articles: DOGS, THE FIRST DOMESTICATED ANIMALS? europe.factsanddetails.com WHEN WERE DOGS FIRST DOMESTICATED europe.factsanddetails.com

Early Development of Dogs and Dog Breeds

Early dogs were smaller and the had relatively smaller snouts than wolves. When dogs were first domesticated their snouts and brain cases changed shape. Over time dogs developed tame dispositions. Their teeth and skulls grew smaller as they no longer needed to bring down large prey. Their brains became smaller as their diet switched from meat to human garbage (brains require a lot of calories and protein for growth and maintenance).

Early dogs were used for hunting and consumed for food. They also likely proved themselves useful by eating garbage, warning humans of danger and keeping people warm. In the Middle East dogs were used for hunting and herding wild goats and sheep and later used to herd domestic version of these animals.

Early dogs were medium size and resembled the skittish brown dogs found meekly scavenging around Third World villages. It is believed that the earliest breeds emerged as early people raised dogs that were good at things like guarding and hunting. Environment was also important. In cold climates, large dogs with thick coats have better chances at survival and reproduction than small, short-haired varieties.

Later humans began crossbreeding dogs with desirable characteristics that gave birth to the breeds we know today. In the mid 1800s, kennel clubs were established that officially recognized breeds and encouraged the development of new breeds. Most recently created breeds were created for their appearance.

Five Types of Dogs Existed by End of Ice Age

The Telegraph reported: Man and dog have been best friends for so long that by the end of the Ice Age there were five different types of dog, new research has found.After molecular evidence showed all dogs are descended from the gray wolf, the new findings have shed more light on how different lineages of canine went on to develop. Diversity among dogs first developed while humans were still hunters and gatherers, according to a study conducted by the Francis Crick Institute at the University of Oxford. [Source: Dominic Penna, The Telegraph, October 30, 2020]

“Dogs were domesticated around 15,000 years ago and spread across large parts of the world within 4,000 years, according to Dr Anders Bergström, a researcher at the Crick’s ancient genomics laboratory and the lead author of the study. “We can see in the genomes that by at least 11,000 years ago, they had already started to diversity into distinct lineages and spread across large parts of the world,” he told The Telegraph. “We don’t really know how dogs were able to spread so quickly across the world, but by the end of the Ice Age dogs were already present throughout much of the northern hemisphere.” He said it is still “a bit of a mystery” as to how dogs dispersed so rapidly without any large-scale human migrations, but they nonetheless developed different genetic profiles on different continents.

“The study also found that dogs have become less genetically diverse throughout Europe, with ancient European beasts having displayed much greater diversity than dogs today, although it is not yet understood how this process happened. Dr Bergström added that “there is a correlation” between the different histories of dogs and humans, although these occasionally diverged when humans migrated to different parts of the world without their four-legged friends in tow. “There is a correlation, so dogs would often follow humans as humans moved and migrated and mixed in different parts of the world,” he said.The findings were published yesterday in the journal Science.

Paul Rincon of the BBC wrote : Early European dogs were initially diverse, appearing to originate from two very distinct populations, one related to Near Eastern dogs and another to Siberian dogs. “But at some point, perhaps after the onset of the Bronze Age, a single dog lineage spread widely and replaced all other dog populations on the continent. This pattern has no counterpart in the genetic patterns of people from Europe. Anders Bergström, lead author and post-doctoral researcher at the Crick, said: "If we look back more than four or five thousand years ago, we can see that Europe was a very diverse place when it came to dogs. Although the European dogs we see today come in such an extraordinary array of shapes and forms, genetically they derive from only a very narrow subset of the diversity that used to exist." [Source: Paul Rincon, BBC, October 30, 2020]

“The results reveal that breeds like the Rhodesian Ridgeback in southern Africa and the Chihuahua and Xoloitzcuintli in Mexico retain genetic traces of ancient indigenous dogs from the region. The ancestry of dogs in East Asia is complex. Chinese breeds seem to derive some of their ancestry from animals like the Australian dingo and New Guinea singing dog, with the rest coming from Europe and dogs from the Russian steppe. The New Guinea singing dog is so named because of its melodious howl, characterised by a sharp increase in pitch at the start.

Coywolves and Dog-Fox Hybrids

Live Science reported: Wolves, dogs and coyotes are all capable of breeding with one another to create hybrids. This mixing usually happens in captivity, with humans forcing different canids together, but the three have also crossed in the wild. Eastern coyotes are commonly called coywolves or coydogs because they bred with wolves and dogs in generations past — making them bigger than western coyotes but smaller than wolves. Modern eastern coyotes now keep to their own kind. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, October 25, 2023]

In 2021, people in Brazil discovered what they believed to be the world's first dog-fox hybrid, a finding confirmed in 2023 with genetic testing. Chris Malone Méndez wrote in Men's Journal: The hybrid is known as a "dogxim," a cross between a dog and a graxaim-do-campo, the Portuguese name for a Pampas fox. This specific female dogxim was hit by a car and taken to a wildlife rehabilitation facility. where the staff noticed she had a strange mix of different physical features and behaviors. [Source: Chris Malone Méndez, Men's Journal, October 3, 2023]

According to Dr. Jacqueline Boyd, a senior lecturer in animal science at Nottingham Trent University, the presence of the dogxim likely points to an increase in contact between wild and domestic species. That shouldn't come a surprise considering the expansion of human settlements in wild habitats. But besides displacing the animals and running the chance of making a non-endangered creature like the Pampas fox endangered, it also increases the risk of disease transmission between species.

In the case of the original dogxim, she reportedly died in the months after her rehabilitation, making it harder for scientists to research questions about things like fertility. We probably shouldn't expect to see many dog-fox hybrids running around anytime soon, especially since the common red fox is genetically more distant from the common house dog (Canis lupus familiaris) than the Pampas fox. Still, it might not be a totally uncommon sight in the coming decades if human habitats continue to grow.

World’s Largest and Smallest Dogs

According to Guinness World Records, the tallest living dog as of 2024 — a Great Dane named Kevin, living in West Des Moines, Iowa in the U.S. — stands almost a meter tall (96 centimeters (3 feet, 2 inches tall) . The previous record holder was Great Dane named Zeus, another Great Dane, from Texas, previously held the Guinness record for the world's tallest living dog. He stood over a meter (1.04 meters, 3 feet, 5.18 inches) tall. [Source: Natalie Neysa Alund, USA TODAY, June 14, 2024; Liam Gravvat, USA TODAY, November 11, 2022]

According to Guinness the longest and heaviest dog ever recorded was Aicama Zorba of La-Susa, an Old English Mastiff owned Chris Eraclides of London, England. In 1987, Zorba weighed 343 pounds and measured 8 feet, 3 inches from nose to tail. According to Purina, the pet food company, the English Mastiff is the biggest dog breed in the world, says Purina. It reaches height of 69 to 89 centimeters (27 to 35 inches) and a weight of 90 to 104 kilograms (200 to 230 pounds). The Romans kept mastiffs and today English mastiffs serve as police, military, security, and guard dogs. The second largest dog breed is is the Irish Wolfhound. According to Purina, these dogs can grow up to 81 centimeters (32 inches) but are known for having a gentle disposition.

As of 2024, the shortest living dog was a Chihuahua named Pearl, according to Guinness. She is only 9.1 centimeters (3.59 inches) tall and 12.7 centimeters (5 inches) in length — about the size of a smart phone. Pearl weighs 0.55 kilograms (1.22 pound) and is the niece of previous title holder Milly, a 0.45-kilogram (1-pound) Chihuahua born in 2011, who died in 2020. Milly measured 9.65 centimeters (3.8 inches) tall.

Chihuahuas are the smallest dog breed in the world. They range from 15 to 23 centimeters (5.9 to 9 inches) in height, according to Purina, They weigh 1.8 to 2.7 kilograms (four to six pounds) and come short hair and longer hair varieties. According to the AKC Chihuahuas are “sassy pets” with “huge personalities”. Purina lists toy poodles as the second smallest dog. They do not exceed 28 centimeters (11 inches in height). AZ Animals says they weigh between 2.7 and 4.5 kilograms (six and 10 pounds) and can live up to 18 years.

Oldest, Fastest and Highest-Jumping Dogs

The oldest dog in the world was an Australian cattle dog named Bluey who lived to the age of 29 years and 5 months. Bluey died in 1939, AZ Animals says, and she lived over double the average lifespan of her breed. The oldest living dog as of 2023 was Toy Fox Terrier named Pebbles named who reached her 23rd birthday on March 28, 2023. [Source: Liam Gravvat, USA TODAY, November 11, 2022]

Bobi, a purebred Portuguese Rafeiro do Alentejo, was recognized as the world's oldest dog but was later stripped of the title. It was said he reached the age of 31 years and 165 days. His owner, Leonel Costa, attributes his long life to a calm environment, a simple diet, and a life free from leashes, allowing him to roam freely on the farm. While Bobi's age was initially confirmed by the Portuguese government's pet database, Guinness World Records reviewed the evidence and the placed the title on hold, according to the BBC and NPR, and then took it away. Bobi was reportedly born on May 11, 1992 and died October 21, 2023. He and Costa lived in Conqueiros, Leiria, Portugal. Bobi was claimed to be the first dog on record to reach 30 years of age. On February 2, 2023, Bobi was certified by Guinness World Records as the oldest living dog, along with being the oldest dog on record to ever live. However, after veterinarians became suspicious of his real age, an investigation was undertaken and the records were revoked. [Source: Yahoo News, Wikipedia]

Greyhounds are the fastest dogs, with a a top speed of 67 kilometers per hour (42 miles per hour). According to Reader Digest: Standing up to 76 centimeters (30 inches) high at the shoulder, greyhounds are among the fastest sprinters on the planet. Like cheetahs, they run in a double suspension gallop, meaning that their bodies contract and extend as they run, with all four feet leaving the ground in each movement. In fact, when a greyhound runs, its feet are touching the ground only 25 percent of the time!The fastest dog in the world can reach top speed within six strides. Otherwise, they are known as couch potatoes who sleep about 18 hours a day! Because of this they good apartment dogs. [Source: Elizabeth Heath,Reader Digest, June 15, 2024]

Greyhounds are also the highest jumpers. According to Guinness World Records, the highest jump by a dog is 191.7 centimeters (75.5 inches — by Feather in Frederick, Maryland, in the U.S. on September 14, 2017. Feather is a female greyhound owned and cared for by Samantha Valle. She was two years old when she made the jump.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Dog Origin sites map, Discover magazine

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025