Home | Category: First Modern Human Life / Life and Culture in Prehistoric Europe

DOG DOMESTICATION

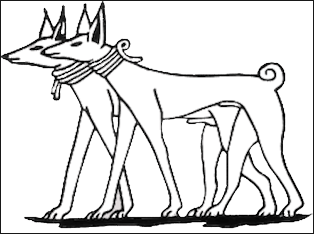

dogs in ancient Egypt

Dogs are believed to have been the first animals to be domesticated by ancient humans. Most archaeologists believe that dogs were first domesticated about 14,000 years ago. This was before the development of agriculture and permanent human settlements. There are currently about 400 million dogs in the world and 400,000 wolves. [Source: Xiaoming Wang and Richard Tedford, Natural History magazine, July-August 2008; Angus Phillips, National Geographic, January 2002]

Humans and wolves or proto dogs came together perhaps because they traveled in groups of about the size, inhabited the same areas and hunted the same prey and were able to help each other: with their sensitive noses dogs were good at locating prey, with their tools and weapons and skills early humans were good at killing large animals. It seems likely that wolves or proto dogs lurked around early human camps.

Offering a scenario of how dogs and humans came together Rudyard Kipling wrote in "Just So Stories" in 1912: "The Woman picked up a roasted mutton-bone and threw it to Wild Dog, and said, “Wild Dog,” and said, 'Wild Thing out of the Wild Woods, taste and try.' Wild Dog gnawed the bone, and it was more delicious than anything he had ever tasted, and he said, 'O my Enemy and Wife of my Enemy, give me another.'..,"The Woman said, 'Wild Thing out of the Wild Woods, help my Man to hunt through the day and guard this cave at night, and I will give you as many roast bones and you need."

Jeff MacGregor wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Over thousands of years, evolution selected and sharpened in dogs the traits most likely to succeed in harmony with humans. Wild canids that were affable, nonaggressive, less threatening were able to draw nearer to human communities. They thrived on scraps, on what we threw away. Those dogs were ever so slightly more successful at survival and reproduction. They had access to better, more reliable food and shelter. They survived better with us than without us. We helped each other hunt and move from place to place in search of resources. Kept each other warm. Eventually it becomes a reciprocity not only of efficiency, but of cooperation, even affection. Given enough time, and the right species, evolution selects for what we might call goodness. This is the premise of Hare and Woods’ new book, Survival of the Friendliest. [Source: Jeff MacGregor; Smithsonian magazine, December 2020]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WHEN AND WHERE DOGS WERE FIRST DOMESTICATED europe.factsanddetails.com

DOGS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND INTELLIGENCE europe.factsanddetails.com

DOG AND WOLF HISTORY: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, HYBRIDS AND RECORDS europe.factsanddetails.com

WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, SPECIES, NUMBERS factsanddetails.com

CANIDS, CANINES AND CANIS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WOLF BEHAVIOR: PACKS, HIERARCHIES, MATING, PUPS factsanddetails.com;

GRAY WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WOLF FOOD: DIET, HUNTING: PREY, TACTICS, FEEDING HABITS factsanddetails.com;

WOLVES AND HUMANS: STORIES, LIVESTOCK, REWILDING factsanddetails.com

WOLF ATTACKS ON HUMANS: WHERE, WHY, WHEN, HOW factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Dog's History of the World: Canines and the Domestication of Humans”

by Laura Hobgood-Oster (2014) Amazon.com;

“Dogs: Archaeology beyond Domestication” by Brandi Bethke and Amanda Burtt Amazon.com;

“The Dog: A Natural History” by Ádám Miklósi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Our Oldest Companions: The Story of the First Dogs” by Pat Shipman (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction”

by Pat Shipman Amazon.com;

“Dogs: A New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution” (2002) by Raymond Coppinger, Lorna Coppinger Amazon.com;

“First Dog on Earth, How It All Began | An Odyssey of Survival and Trust (Novel)

by Irv Weinberg (2021) Amazon.com;

“Domesticated: Evolution in a Man-Made World” by Richard C. Francis Amazon.com;

“The Process of Animal Domestication” by Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Dog Breed Book, New Edition” by DK (2020) Amazon.com;

“The New Complete Dog Book” by the American Kennel Club (2017)

(2017) Amazon.com;

Theories on Dog Domestication

Some scholars believe early humans adopted wolf pups. Some say early pets were orphaned animals that were found and kept in camps and perhaps even milk from the breast. Others believe that dogs domesticated themselves by scavenging garbage dumps and succeeding generation became less fearful of humans. The animals, perhaps attracted by the smell of meat, approached early human camps. The humans offered them food, the animals hung around and a bond was established that was passed to later generations, with natural selection favoring those less aggressive and better at begging for food. The submissive behavior that subordinate dogs express to dominate dogs and puppies show their mother was extrapolated from dogs to humans.

Monte Morin wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Since the time of Charles Darwin, scientists have argued over the origin of domesticated dogs, speculating wildly about how, when and where a toothy, flesh-eating beast was first transformed into man’s best friend. Some experts believe humans were naturally drawn to small, furry wolf pups, and seized them as novelties. Others suggest they were raised for slaughter by early agrarian societies. Yet another theory holds that early proto-dogs were enlisted as helpers by roving bands of hunters, long before humankind ever experimented with agricultural livestock. [Source: Monte Morin, Los Angeles Times, November 14, 2013]

“Until recently, many archaeologists and biologists believed that dogs were first domesticated no more than 13,000 years ago, either in East Asia or the Middle East. A burial site in Israel contained the 12,000-year-old remains of an elderly man cradling a puppy. Archaeologists pointed to this find, as well as others, as evidence of a special, ancient bond between dogs and humans. Yet tracing the exact path of dog evolution has been extremely difficult. Ancient dog remains are hard to distinguish from wolf remains, and frequent interbreeding between dogs and wolves further complicate matters. Add to that mankind’s zealous breeding of the animals to enhance specific traits and behaviors and the genetic waters become very clouded.

“In fact, Darwin himself believed that the dizzying variety of existing dog breeds argued strongly that dogs must have had more than one wild ancestor. Genetic researchers today say this is most likely not the case, and that domesticated dogs evolved from one ancestor, in one region. “On some levels, understanding the geographic origins of dogs is definitely more difficult than studying humans,” said Greger Larson, a bioarchaelogist at the University of Durham in England.”

Study of the First Domesticated Dogs

wolf Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine, “Just how and when the species first became recognizably "doggy" has preoccupied scientists since the theory of evolution first gained widespread acceptance in the 19th century. The idea that dogs were domesticated from jackals was long ago discarded in favor of the notion that dogs descend from the gray wolf, Canis lupus, the largest member of the Canidae family, which includes foxes and coyotes. While no scholars seriously dispute this basic fact of ancestry, biologists, archaeologists, and just about anyone interested in the history of dogs still debate when, where, and how gray wolves first evolved into the animal that is the ancestor of all dog breeds... Were the first dogs domesticated in China, the Near East, or possibly Africa? Were they first bred for food, companionship, or their hunting abilities? The answers are important, since dogs were the first animals to be domesticated and likely played a critical role in the Neolithic revolution. Recently, biologists have entered the debate, and their genetic analyses raise new questions about when and where wolves first developed into what we today recognize as dogs.[Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

The archaeological record suggests dogs were domesticated in multiple places at different times, but in 2009, a team led by Peter Savolainen of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm published an analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of some 1,500 dogs from across the Old World, which narrowed down the time and place of dog domestication to a few hundred years in China. "We found that dogs were first domesticated at a single event, sometime less than 16,300 years ago, south of the Yangtze River," says Savolainen, who posits that all dogs spring from a population of at least 51 female wolves, and were first bred over the course of several hundred years. "This is the same basic time and place as the origin of rice agriculture," he notes. "It's speculative, but it seems that dogs may have first originated among early farmers, or perhaps hunter-gatherers who were sedentary."

In 2010 a team led by biologist Robert Wayne of the University of California, Los Angeles, showed that domesticated dog DNA overlaps most closely with that of Near Eastern wolves. Wayne and his colleagues suggest that dogs were first domesticated somewhere in the Middle East, then bred with other gray wolves as they spread across the globe, casting doubt on the idea that dogs were domesticated during a single event in a discrete location. Savolainen maintains that Wayne overemphasizes the role of the Near Eastern gray wolf, and that a more thorough sampling of wolves from China would support his team's theory of a single domestication event.

University of Victoria archaeozoologist Susan Crockford, who did not take part in either study, suspects that searching for a single moment when dogs were domesticated overlooks the fact that the process probably happened more than once. "We have evidence that there was a separate origin of North American dogs, distinct from a Middle Eastern origin," says Crockford. "This corroborates the idea of at least two 'birthplaces.' I think we need to think about dogs becoming dogs at different times in different places." As for how dogs first came to be domesticated, Crockford, like many other scholars, thinks dogs descend from wolves that gathered near the camps of semi-sedentary hunter-gatherers, as well as around the first true settlements, to eat scraps. "The process was probably driven by the animals themselves," she says. "I don't think they were deliberately tamed; they basically domesticated themselves." Smaller wolves were probably more fearless and curious than larger, more dominant ones, and so the less aggressive, smaller wolves became more successful at living in close proximity to humans. "I think they also came to have a spiritual role," says Crockford. "Dog burials are firm evidence of that. Later, perhaps they became valued as sentries. I don't think hunting played a large role in the process initially. Their role as magical creatures was probably very important in the early days of the dog-human relationship." [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

Did Ice Age Humans Domesticate Wolves by Sharing Leftover Meat with Them

A study published in January 2021 in the journal Scientific Reports suggested that early human hunters began bonding with dogs in northern Eurasia between 14,000 and 29,000 years ago and did so by sharing leftovers from their kills. The study argues that human hunters killed more game than they could eat during, and rather than waste the excess meat, they fed it to wolves, which evolved into domesticated dogs. [Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, January 9, 2021]

Aylin Woodward wrote in Business Insider: “Plants were scarce and prey was lean during those harsh Ice Age winters. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors could only get all 45 percent of the calories they needed to survive from eating lean meat, since too much can cause protein poisoning (human livers aren't well-adapted to metabolizing protein). In the absence of plant-based carbs, our ancestors relied on animal fat and grease to supplement their diet.

To get enough fat, though, hunters had to kill more lean animals like deer and moose than they could eat in their entirety. So Ice Age hunters fed the excess meat to wolves, according to Maria Lahtinen, the lead author of the new study and an archaeologist with the Finnish Food Authority. “The wolf and human can form a partnership without competition in cold climate. This would easily promote domestication," Lahtinen told Business Insider. The descendants of the leftover-eating wolves eventually became the first domesticated dogs, her study suggests.

Ancient humans and the northern wolves that occupied Eurasia tens of thousands of years ago subsisted on the same prey, like caribou, rabbits, and deer. It struck many researchers as unlikely that the two species would have willingly chosen to cooperated given the limited food sources during the Ice Age. “Humans have a tendency to try to eliminate other competitors," Lahtinen said, adding, "it has never been explained before that why humans joined their forces with a competitor."

“Before this study, one hypothesis was that wolves were opportunistic scavengers that were so attracted to the food waste humans left behind that the two species eventually adapted to live alongside one another. The problem with that thinking, however, was that Ice Age humans didn't settle in any one place long enough to leave consistent, scavengeable scraps, according to Lahtinen and her coauthors. So it may be more plausible that our ancestors simply caught more prey than they could safely consume, and chose to satiate their fellow predators rather than kill them off. That led the four-legged predators to stick closer and closer to people over time until they evolved into dogs, a process that took place sometime between 20,000 and 14,000 years ago, Lahtinen's research suggests.

Child in Finland Buried with a Wolf 18,000 Years Ago?

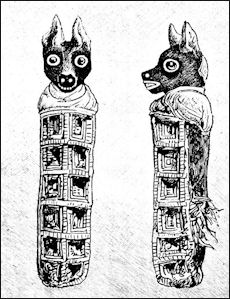

dog mummies Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: A Stone Age burial in Finland holds the remains of a child, as well as an assortment of grave goods, bird feathers, canine hairs and plant fibers, giving archaeologists insight into burial practices from that time period. First discovered in 1991 in Majoonsuo, an archaeological site near the town of Outokumpu in eastern Finland, the grave contains the teeth of a child, who, based on a dental analysis, died between the ages of 3 and 10. Archaeologists from the Finnish Heritage Agency, a cultural and research institution in Helsinki, determined it was a grave site based on red ochre — an iron-rich soil commonly associated with burial sites and rock art — that had stained a gravel roadway. The agency’s excavation team examined the site in 2018. The findings were published September 27, 2022 in the journal PLOS One.[Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, November 7, 2022]

Based on the trapezoidal shape of two arrowheads made of quartz, the archaeologists determined that the grave dates to the Mesolithic period, or Middle Stone Age, roughly 8,000 years ago. After analyzing soil samples, the researchers discovered barbules from the feathers of waterfowl that could have been used to create a bed of down feathers for the child; they also found a single falcon feather fragment. This falcon feather may have been fletching that helped guide an arrow, or perhaps a decoration on a garment, the researchers said.

At the base of the burial lay 24 fragments of mammalian hair. While many of the hairs were badly degraded, the researchers determined that three came from a canine, possibly a wolf or a dog that may have been laid at the feet of the child as part of the burial. It's also possible that the canid hairs came from clothing, such as footwear crafted from dogskin or wolfskin, worn by the child, the teams noted.

"Dogs interred with the deceased have been found in, for example, Skateholm, a famous burial site in southern Sweden dating back some 7,000 years," Kristiina Mannermaa, a researcher and associate professor in the Department of Cultures at the University of Helsinki, said in the statement. "The discovery in Majoonsuo is sensational, even though there is nothing but hairs left of the animal or animals — not even teeth. We don't even know whether it's a dog or a wolf." She added, "The method used demonstrates that traces of fur and feathers can be found even in graves several thousands of years old, including in Finland."

In addition, archaeologists unearthed plant fibers, possibly from willows or nettles, that might have been used to make clothing or fishing nets. Because soil in this area of Finland is highly acidic, the archaeologists were surprised at how well some of the organic remains have lasted over the centuries. "The work is really slow and it really made my heart jump when I found minuscule fragments of past garments and grave furnishings, especially in Finland, where all unburnt bones tend to decompose," study lead author Tuija Kirkinen, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Cultures at the University of Helsinki, told CNN. "This all gives us a very valuable insight about burial habits in the Stone Age, indicating how people had prepared the child for the journey after death."

Ancient DNA Says Domesticated Dogs Existed 11,000 Years Ago and Developed with Humans

According to a global study of ancient DNA study published in Science in October 2020, much of the diversity present in modern dog populations was already there 11,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age. The study showed how dogs and humans spread together around the globe, with a few period in which they appeared to separate. The research was carried out by a team from the Francis Crick Institute based on the genomes sequenced from 27 dogs, some of which lived nearly 11,000 years ago, across Europe, the Near East and Siberia. Among other things the scientists that well before the domestication of any other animal, there were already at least five different types of dog with distinct genetic ancestries. [Source: Issam Ahmed, AFP, October 30, 2020]

“Pontus Skoglund of Crick's Ancient Genomics laboratory, the paper's senior author, said: "Some of the variation you see between dogs walking down the street today originated in the Ice Age. “By the end of this period, dogs were already widespread across the northern hemisphere." He added this implied that the diversity arose far earlier, "way back in time, during the hunter gatherer Stone Age, the Paleolithic, way before agriculture."

AFP reported: “The paper support the idea that, unlike other animals such as pigs which appear to have been domesticated in multiple locations over time, there is a "single origin" from wolves to dogs. The scientists found that all dogs probably share a common ancestry "from a single ancient, now-extinct wolf population," with limited gene flow from wolves since domestication but substantial dog-to-wolf gene flow.

By extracting and analyzing ancient DNA from skeletal material, the researchers were able to see evolutionary changes as they occurred thousands of years ago. For instance, European dogs around four or five thousand years ago were highly diverse and appeared to originate from highly distinct populations from Near Eastern and Siberian dogs. But over time, this diversity was lost. “Although the European dogs we see today come in such an extraordinary array of shapes and forms, genetically they derive from only a very narrow subset of the diversity that used to exist," said the paper's lead author Anders Bergstrom.

“Evolutionary pathways between our two species have at times followed similar routes. Humans, for example, have more copies than chimpanzees of a gene that creates a digestive enzyme called salivary amylase, which helps us break down high-starch diets. Likewise, the paper demonstrated that early dogs carried extra copies of these genes compared to wolves, and this trend only increased over time as their diets adapted to agricultural life. This builds on previous research that found Arctic sled dogs, like Inuits, have evolved similar metabolic pathways to allow them to process high-fat diets. There have also been periods when our histories have not run in parallel — for example the loss of diversity that once existed in dogs in early Europe was caused by the spread of single invasive species, an event not mirrored in human migrations.

Paul Rincon of the BBC wrote :“The results suggest all dogs derive from a single extinct wolf population — or perhaps a few very closely related ones. If there were multiple domestication events around the world, these other lineages did not contribute much DNA to later dogs. “Dr Skoglund said it was unclear when or where the initial domestication occurred. "Dog history has been so dynamic that you can't really count on it still being there to readily read in their DNA. We really don't know — that's the fascinating thing about it." [Source: Paul Rincon, BBC, October 30, 2020]

Greek vase depiction of boar hunting

Dogs at Natufian Sites in the Middle East 11,500 Years Ago

At Natufian sites is some of the earliest archaeological evidence of dog domestication. At the Natufian site of Ain Mallaha in Israel, dated to 12,000 B.C., an elderly human and a four-to-five-month-old puppy were found buried together. At another Natufian site, the cave of Hayonim, humans were found buried with two dogs. +

The Natufians were mostly hunter-gatherers who lived in modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria approximately 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. Merging nomadic and settled lifestyles, they were among the first people to build permanent houses and cultivate edible plants. The advancements they achieved are believed to have been crucial to the development of agriculture during the time periods that followed them.

According to Archaeology magazine: Canine bones from a site called Shubayqa 6 in Jordan indicate that the mutually beneficial relationship dates back at least 11,500 years. Researchers found a sharp increase in the number of small animal bones at the site dating to this same period. This suggests dogs may have helped humans catch smaller, more elusive prey such as hares, perhaps by driving them into nets or enclosures. [Source: Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

Dogs and Humans Become Especially Close When Agriculture Took Hold?

David Brown wrote in the Washington Post: “A team of Swedish researchers compared the genomes of wolves and dogs and found that a big difference is dogs’ ability to easily digest starch. On their way from pack-hunting carnivore to fireside companion, dogs learned to desire — or at least live on — wheat, rice, barley, corn and potatoes. As it turns out, the same thing happened to humans as they came out of the forest, invented agriculture and settled into diets rich in grains. “I think it is a striking case of co-evolution,” said Erik Axelsson, a geneticist at Uppsala University. “The fact that we shared a similar environment in the last 10,000 years caused a similar adaptation. And the big change in the environment was the development of agriculture.” [Source: David Brown, Washington Post, January 23, 2013 ]

“The findings, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, support the hypothesis that dogs evolved from wolves who found a new food source in refuse on the outskirts of human settlements. Eventually they came to tolerate human contact and were brought into the household to be guards, workers and companions. Archaeological remains reveal dogs and humans sharing the same graves 11,000 years ago. That was at the dawn of agriculture; the two species appear to have been at least acquaintances by then. “Pretty much everyone without an agenda agrees that we don’t really have a good handle about why wolves domesticated into dogs when they did,” said Adam Boyko, a geneticist at Cornell University who studies dog evolution and was not involved in the new research. “But it does seem reasonable, and in agreement with the fossil and genetic record, that it could have predated agriculture somewhat.”

“The evidence of natural selection in the number and efficiency of key digestive enzymes supports the hypothesis that dogs may have domesticated themselves as a way to exploit the garbage of permanent human settlements.“Humans had nothing to do with it,” said Raymond Coppinger, an emeritus professor of biology and expert on dog evolution at Hampshire College in Massachusetts. “There was a new niche that was all of a sudden available for somebody to move into. Dogs are selected to scavenge off people.” Accompanying the dietary change — and probably evolving along with it — were behavior changes that allowed dogs to tolerate living near people and ultimately being adopted by them. The Swedish researchers found strong evidence of genetic differences in brain function — and particularly brain development — between wolves and dogs, which they have not yet analyzed.

“In the new study, Axelsson and his colleagues examined DNA from 12 wolves and 60 dogs. The wolf samples were from animals from the United States, Sweden, Russia, Canada and several other northern countries. The dogs were from 14 breeds. The researchers compared the DNA sequences of the wolves and the dogs (which are subspecies of the same species, Canis lupus) and identified 36 genomic regions in which there are differences that suggest they have undergone recent natural selection in dogs.

Egyptian and Assyrian dogs

“In particular, dogs show changes in genes governing three key steps in the digestion of starch. The first is the breakdown of large carbohydrate molecules into smaller pieces; the second is the chopping of those pieces into sugar molecules; the third is the absorption of those molecules in the intestine. “It is such a strong signal that it makes us convinced that being able to digest starch efficiently was crucial to dogs. It must have been something that determined whether you were a successful dog or not,” Axelsson said.

“The change is at least partly the consequence of dogs having multiple copies of a gene for amylase, an enzyme made by the pancreas that is involved in the first step of starch digestion. Wolves have two copies; dogs have four to 30. As it happens, amylase “gene duplication” is also a feature of human evolution. Humans carry more copies of the amylase gene than their primate ancestors. People also produce the enzyme in saliva, which allows the first steps of digestion to occur while food is still in the mouth. That, in turn, rewards chewing and increases the palatability of food. In dogs, however, the increased amylase activity occurs only in the pancreas. The enzyme isn’t at work in their mouths, probably because the food doesn’t stay there long enough. Dogs may be able to eat human food, but they still wolf it down.

“The researchers found 19 genome regions containing nervous system genes that are significantly different between wolves and dogs. Eight regions contain genes governing brain development. Sociability around strangers, curiosity and playfulness are traits seen in both wolf pups and dog pups. So are floppy ears, broader faces and liberal tail-wagging. They all persist in adult dogs but are largely extinguished in adult wolves. This retention of juvenile traits into adulthood — a phenomenon known as “neoteny” — is a key feature of domestication, some biologists believe. In a famous four-decade, 40-generation experiment in Russia, these traits emerged in foxes when scientists selectively bred the animals for tameness.

“But the process may not require human intervention. Similar behavior probably evolved naturally in dogs. The willingness to wander fearlessly among people is a big plus if scavenging human food is your business (as it still is for millions of “village dogs” around the world). There’s a theory that this “self-domestication” also happened in the evolution of Homo sapiens. As people created permanent settlements — and running away from those you didn’t like (or killing them) became less of an option — there may have been a survival advantage to being cooperative and self-controlled. It’s possible that studying the genes that determine dog sociability might shed light on how a less aggressive, more civilized human evolved, Axelsson said.”

10,000-Year-Old Remains Suggest Domestic Dogs Accompanied First Humans in America

In February 2021, in a study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, scientists said they had discovered the oldest remains of a domestic dog in the Americas dating back more than 10,000 years, suggesting the animals accompanied the first waves of human settlers. According to AFP: “Humans are thought to have migrated to North America from Siberia over what is today the Bering Strait at the end of the last Ice Age — between 30,000 and 11,000 years ago.

The study led by the University at Buffalo analysed the mitochondrial DNA of a bone fragment found in Southeast Alaska. The team initially thought the fragment belonged to a bear. But closer examination revealed it to be part of a femur of a dog that lived in the region around 10,150 years ago, and that shared a genetic lineage with American dogs that lived before the arrival of European breeds. "Because dogs are a proxy for human occupation, our data help provide not only a timing but also a location for the entry of dogs and people into the Americas," said Charlotte Lindqvist, an evolutionary biologist from the University at Buffalo and the University of South Dakota.

“She said the findings, upports the theory that humans arrived in North America from Siberia. “Southeast Alaska might have served as an ice-free stopping point of sorts, and now — with our dog — we think that early human migration through the region might be much more important than some previously suspected," said Lindqvist. A carbon isotope analysis of the bone fragment showed that the ancient Southeast Alaskan dog likely had a marine diet that consisted of fish and seal and whale scraps.

“Lindqvist said dogs did not arrive in North America all at once. Some arrived later from East Asia with the Thule people, while Siberian huskies were imported to Alaska during the Gold Rush in the 19th century. Previous age estimates of dog remains were younger than the fragment found by Lindqvist and the team, suggesting that dogs arrived in the continent during the later, continental migrations.

“Lindqvist said her findings supported the theory that dogs in fact arrived in North America among the first waves of humans settlers. “We also have evidence that the coastal edge of the ice sheet started melting at least around 17,000 year ago, whereas the inland corridor was not viable until around 13,000 years ago," she told AFP, . “And genetic evidence that a coastal route for the first Americans over 16,000 years ago seems most likely. Our study supports that our coastal dog is a descendant of dogs that participated in this initial migration."

Dogs Domesticated in Siberia Before Their Arrival in America?

Kurdish mastiff on an Assyrian tablet

Scholars who have studied the genetic and archaeological record of the first wave of hunter gatherers to migrate from Asia to America determined that dogs were already domesticated when the first America settlers arrived. The The Telegraph reported: Dr Angela Perri of Durham University believes wild canines first became human companions in Siberia around 23,000 years ago.Dogs were then spread across the world with their hunter-gatherer owners and crossed over to North America around 15,000 years ago, according to Dr Perri’s team of international academics. She said: "By putting together the puzzle pieces of archaeology, genetics and time we see a much clearer picture where dogs are being domesticated in Siberia, then disperse from there into the Americas and around the world." [Source: The Telegraph, January 25, 2021]

Geneticist Laurent Frantz of Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich said: "The only thing we knew for sure is that dog domestication did not take place in the Americas. “From the genetic signatures of ancient dogs, we now know that they must have been present somewhere in Siberia before people migrated to the Americas."

“Archaeologist David Meltzer of Southern Methodist University in Dallas, said: "We have long known that the first Americans must have possessed well-honed hunting skills, the geological know-how to find stone and other necessary materials. “The dogs that accompanied them as they entered this completely new world may have been as much a part of their cultural repertoire as the stone tools they carried."

9,400-Year-Old Domesticated Dog, a Food Source in the Americas?

In 2011, AP reported: “Nearly 10,000 years ago, man's best friend provided protection and companionship — and an occasional meal. That's what researchers are saying after finding a bone fragment from what they are calling the earliest confirmed domesticated dog in the Americas. [Source: Clarke Canfield, Associated Press, January 19, 2011]

University of Maine graduate student Samuel Belknap III came across the fragment while analyzing a dried-out sample of human waste unearthed in southwest Texas in the 1970s. A carbon-dating test put the age of the bone at 9,400 years, and a DNA analysis confirmed it came from a dog — not a wolf, coyote or fox, Belknap said. Because it was found deep inside a pile of human excrement and was the characteristic orange-brown color that bone turns when it has passed through the digestive tract, the fragment provides the earliest direct evidence that dogs — besides being used for company, security and hunting — were eaten by humans and may even have been bred as a food source, he said.

Belknap wasn't researching dogs when he found the bone. Rather, he was looking into the diet and nutrition of the people who lived in the Lower Pecos region of Texas between 1,000 and 10,000 years ago. "It just so happens this person who lived 9,400 years ago was eating dog," Belknap said.

Belknap and other researchers from the University of Maine and the University of Oklahoma's molecular anthropology laboratories, where the DNA analysis was done, have written a paper on their findings. The paper was published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. For his research, Belknap — who does not own a dog himself — had fecal samples shipped to him that had been unearthed in 1974 and 1975 from an archaeological site known as Hinds Cave and kept in storage at Texas A&M University. The fragment is about six-tenths of an inch long and three- to four-tenths of an inch wide, or about the size of a fingernail on a person's pinkie.

Belknap and a fellow student identified the bone as a fragment from where the skull connects with the spine. He said it came from a dog that probably resembled the small, short-nosed, short-haired mutts that were common among the Indians of the Great Plains.Judging by the size of the bone, Belknap figures the dog weighed about 25 to 30 pounds. He also found what he thinks was a bone from a dog foot, but the fragment was too small to be analyzed. Other archaeological digs have put dogs in the U.S. dating back 8,000 years or more, but this is the first time it has been scientifically proved that dogs were here that far back, he said.

Darcy Morey, a faculty member at Radford University who has studied dog evolution for decades, said a study from the 1980s dated a dog found at Danger Cave, Utah, at between 9,000 and 10,000 years old. Those dates were based not on carbon-dating or DNA tests, but on an analysis of the surrounding rock layers. "So 9,400 years old may be the oldest, but maybe not," Morey told AP in an e-mail. Morey, whose 2010 book, "Dogs: Domestication and the Development of a Social Bond," traces the evolution of dogs, said he is skeptical about DNA testing on a single bone fragment because dogs and wolves are so similar genetically.

Belknap said there may well be older dogs in North America, but this is the oldest directly dated one he is aware of. For many years, researchers thought that dog bones from an archaeological site in Idaho were 11,000 years old, but additional testing put their age at between 1,000 and 3,000 years old, he said. "If there's one thing our discovery is showing it's that we can utilize these techniques and learn a lot more about dogs in the New World if we apply these tests to all these early samples," he said.

The earliest dogs in North America are believed to have come with the early settlers across the Bering land bridge from Asia to the Americas 10,000 years ago or earlier, said Wayne. It doesn't surprise Belknap that dogs were a source of food for humans. A lot of people in Central America regularly ate dogs, he said. Across the Great Plains, some Indian tribes ate dogs when food was scarce or for celebrations, he said. "It was definitely an accepted practice among many populations," he said.

Russian Steppe Teens Ate Dogs 4,000 Years Ago in Manhood Ritual

According to a paper published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, roasted and chopped bones from at least 64 dogs and wolves, found at the 4000-year-old site of Krasnosamarskoe (Kras-no-sa-MAR-sko-yeh), north of the Caspian Sea in the Russian steppe, were signs of an initiation rite in which teenage boys ate the flesh of dogs at a ritual site to “transform” them into men. [Source: Bridget Alex, Discover, August 8, 2017]

Kurdish shepherd dog

Bridget Alex wrote in Discover: “Initiation rites, in which boys lived in the wild, acting like wolves and dogs, are described in ancient texts of Greek, Latin, Germanic, Celtic, Iranian, and Vedic Sanskrit—all Indo-European cultures that descended from the same ancestral group. Dog- and wolf-themed initiations were “very widespread in Indo-European mythology,” says archaeologist David Anthony, who coauthored the study with Dorcas Brown, both of Hartwick College, New York. “This seems to be the first site where we have concrete evidence for the actual existence of this kind of practice.” Moreover, finding a common Indo-European ritual of this age, in this region, adds support to a debated hypothesis: that Indo-European peoples originated on the Pontic-Caspian steppe and spread across Eurasia, aided by their invention of horse-drawn, wheeled vehicles.

“The small settlement of Krasnosamarskoe held a cemetery and two or three buildings, inhabited 3,700-3,900 years ago by people of the Srubnaya culture, sedentary pastoralists of the steppe. Although Srubnaya people left no written records, some say they spoke an Indo-European language based on cultural and genetic similarities with other Indo-European groups. Archaeologists from the U.S. and Russia excavated the site between 1995-2001, to investigate if, in addition to herding, the Srubnaya were also farming, as is the case with most sedentary people. “We found no evidence for agriculture whatsoever,” says Anthony.

“What they did find was chopped dogs and wolves—a lot of them. Dozens of dogs and at least seven wolves comprised 40 percent of the animal bones at Krasnosamarskoe. Other Srubnaya sites had less than 3 percent canid. “It was a surprise. It was anomalous,” says Anthony. He recalls thinking, “uh oh what does this mean?” Butchered dogs are relatively rare from archaeological sites worldwide, according to Lidar Sapir-Hen, an animal bone specialist at Tel Aviv University, Israel, who was not involved in the study. “If they are found they are usually buried complete…eating them is not a common practice,” says Sapir-Hen.

“At Krasnosamarskoe, the dogs and wolves had been roasted, fileted and chopped into bit-sized, 1- to 3-inch pieces. Over the span of about two generations, the canids were killed predominately in winter, based on microscopic analysis of growth lines in their teeth formed annually during warm and cold seasons. Most of the dogs were old, between six and 12 years, and well treated in life; their bones showed few signs of trauma before they were sacrificed. According to Anthony, “They were familiar pets.” Cows, sheep and other animals at the site did not show these patterns. They were killed year-round, sometimes at young ages, and butchered less intensively. While other animals were chopped into eight to 23 pieces, the average dog ended up in 54 parts. “Particularly the dog heads were chopped in a very standardized way with an axe, like somebody who has practiced and done it many times,” adds Anthony. And over 70 percent of the dogs subjected to DNA analysis proved to be male, hinting the canids were involved in male initiation rites.”

Dog Ritual Settlement at Krasnosamarskoe

Bridget Alex wrote in Discover: “The dog remains caused archaeologists to reevaluate other unusual features of the site. For example, although the researchers did not find agricultural plants, they did identify wild ones with medicinal properties, such as Seseli, a sedative possibly given to animals or humans during the rituals. With 27 graves, the site’s cemetery contained mostly children and only 4 complete adults — two males and two females. The adult men had unusual skeletal injuries caused by twisting to their knees, ankles, and lower backs. [Source: Bridget Alex, Discover, August 8, 2017]

“Anthony thinks the adults represent two generations — two couples — of ritual specialists who lived at the site. And the injuries: “This is just speculative… but it might be related to shamanic dancing,” he says. Based on the archaeological finds, researchers concluded that Krasnosamarskoe was a place where males went episodically, over many years, to eat dogs and wolves during rituals overseen by the site’s residents. But to understand the meaning of those rituals, Anthony and Brown reviewed the myths of many ancient and modern cultures. “We start looking for explanations for a male-centered rite of passage in which they’re being symbolically transformed into dogs and wolves,” says Anthony.

“There turned out to be plenty of examples in ancient Indo-European texts. These widespread sources discussed groups of adolescent boys, usually from elite families, who would spend a few years behaving like dogs or wolves in order to be initiated as warrior men. During this period, the teens were permitted to “behave obnoxiously in many ways,” explains Michael Witzel, a scholar of Sanskrit and ancient mythology at Harvard University. “Use words they shouldn’t use…Take away cattle from their neighbors.” The boys could raid, steal and have their way with women. They were landless, with no possessions aside from weapons. And they symbolically became dogs or wolves by assuming canid names, wearing skins and sometimes eating the animals.

“Anthony and Brown propose that Krasnosamarskoe was the place where Srubnaya boys went to become dogs, to become men. According to Witzel, “their evidence fits quite nicely,” with the ancient texts. Regarding the dog remains, archaeologist Paula Wapnish-Hesse, says, they “present a pretty good range of arguments that are traditionally used for identifying ritual in animal bone collections.” An expert in ancient texts and animal bones, Wapnish-Hesse has analyzed the largest known dog cemetery, comprising more than 1,000 skeletons of mostly puppies, buried some 2,500 years ago at the site of Ashkelon, Israel. Their attempt to extrapolate myths to a culture without written texts, is “a very ambitious bite,” she adds. “They’re going out on a limb and it’s good.”

“However, some scholars disagree with the views that the Srubnaya culture belonged to Indo-European traditions, and that Indo-Europeans originated in the steppe. The main alternative hypothesis is that these cultures descend from early farmers of Anatolia, in present-day Turkey. To this objection, Anthony and Brown respond, in the article, that Indo-European languages were spoken across much of Bronze Age Eurasia in this period and “therefore are ‘on the table’ as possible sources of information.”

Faces and Skulls of Urban Foxes Changing Like Early Domesticated Dogs

A study by University of Glasgow researchers published in June 2020 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B shows that foxes in London have stubbier snouts and smaller skull braincases and less extreme size differences between males and females than rural foxes. These changes are similar to those of other wild animals evolved during domestication. The researchers suggest these foxes could be self-domesticating due to the demands of city environments and exposure to humans. Scientists have observed similar changes before in dogs when they became domesticated between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago. [Source: Holly Secon, Business Insider, June 7, 2020]

Hilly Secon wrote in Business Insider: The study looked at 57 female and 54 male red fox skulls from London and the surrounding countryside. The London foxes' substantially shorter, wider snouts and smaller braincases are likely an adaptation to the different requirements of finding food in their urban habitat, the researchers wrote. City foxes rely on scavenging for food scraps, an activity that doesn't require a strong bite to clamp down on bones, for example. Country foxes, meanwhile, need snouts that enable them to quickly bite prey.

The researchers said the adaptations observed among these urban foxes have been seen before in species that had more exposure to humans. Charles Darwin called this "domestication syndrome." "Domestication leads to stereotypical changes across species toward more docile behavior, coat color changes, reduced total brain size, reductions in tooth size, prolongations of juvenile behavior, and changes in craniofacial traits, including a shortened skull," the researchers wrote. These differences can be seen in comparisons between wild cats and domestic ones, and between wolves and dogs.

Fox Domestication?

An ongoing experiment in Siberia has noticed similar changes in foxes there. But in that case, Russian scientists have been trying to turn silver foxes into tame, doglike canines by breeding only the least aggressive ones since 1959. Over time, the foxes have developed less aggressive behavior, as well as stubbier snouts, floppier ears, and more bark-like sounds. [Source: Holly Secon, Business Insider, June 7, 2020]

“Scientists started a breeding project to domesticate wild silver foxes under the supervision of Dmitry Belyayev in Novosibirsk, Russia, in 1959. These similarities suggest that exposure to humans in different locations seems to have similar effects on foxes. Some animal biologists think that was true for dogs as well — that the animals were domesticated many times by different cultures throughout history.

Helen Briggs wrote in the BBC: Scientists were surprised to find a fox buried in a human grave dating back 1,500 years in Patagonia, Argentina. They think the most likely explanation is that the fox was a highly valued companion or pet. A fox of the same species was found in a much older grave in another part of Argentina nearly a decade ago. It may also have been a pet but its diet was not analysed. "This is a very rare find of having this fox that appears to have had such a close bond with individuals from the hunter-gatherer society," said Dr Ophélie Lebrasseur of the University of Oxford. "I think it was more than just symbolic; I really do think it was companionship." [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC, April 10, 2024]

The fox was found at the burial site of Cañada Seca in Argentina, which was once inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers. Teeth of wild foxes have been found in ancient human burial sites across Argentina and Peru, suggesting the animal had symbolic significance. But the discovery of a near-complete skeleton of a fox in a human grave is extremely rare in the worldwide archaeological record. The fox, which goes by the scientific name, Dusicyon avus, was of a medium size weighing 10-15 kilograms. It went extinct around 500 years ago, a few hundred years after domestic dogs arrived in Patagonia. The research was carried out in collaboration with Dr Cinthia Abbona of the Institute of Evolution in Mendoza, Argentina, and published in the journal, RoyalSociety Open Science.

See Separate Article: FOXES AND HUMANS: FOLKLORE, ATTACKS, PETS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Dog Origin sites map, Discover magazine

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024