Home | Category: Early Settlements and Signs of Civilization in Europe / Bronze Age Europe

NEOLITHIC SCANDINAVIA

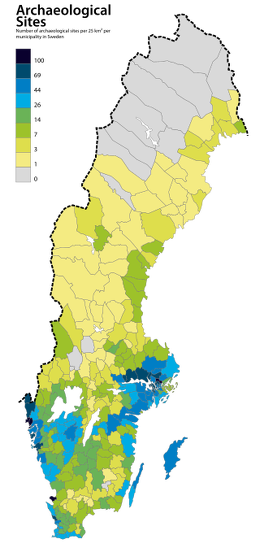

Little evidence remains in Scandinavia of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, or the Iron Age except for tools created from stone, bronze, and iron, some jewelry and ornaments, and stone burial cairns. There is fairly large number of petroglyphs (stone drawings) in the region. During the height of Ice Age glaciations 28,000 years ago almost all of Scandinavia was buried beneath a thick sheet of ice. As the climate slowly warmed up nomadic hunters from central Europe sporadically visited the region, but it was not until around 12,000 B.C. that a permanent, albeit nomadic, population became rooted on the region. [Source: Wikipedia]

As the ice receded, reindeer grazed on the flat lands of Denmark and southernmost Sweden. This was the land of the Ahrensburg culture, tribes who hunted over vast territories and lived in lavvus on the tundra. There was little forest in this region at that timr except for arctic white birch and rowan, but the taiga slowly appeared. From 9,000 to 6,000 years — during Mesolithic period — Scandinavia was inhabited by mobile or semi-sedentary groups people about whom little is known. They subsisted by hunting, fishing and gathering. Approximately 200 burial sites have been investigated in the region from that period.

In the 7th millennium B.C., when the reindeer and their hunters had moved for northern Scandinavia and forests were more established in the land, the Maglemosian culture lived in Denmark and southern Sweden. To the north, in Norway and most of southern Sweden, lived the Fosna-Hensbacka culture, who lived mostly along the edge of the forest. The northern hunter/gatherers followed the herds and the salmon runs, moving south during the winters, moving north again during the summers. During the 6th millennium B.C. southern Scandinavia was covered in temperate broadleaf and mixed forests. Fauna included aurochs, wisent, moose and red deer. The Kongemose culture was dominant in this time period. They hunted seals and fished in the rich waters. North of the Kongemose people lived other hunter-gatherers.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Early Neolithic of Northern Europe: New Approaches to Migration, Movement and Social Connection” by Daniela Hofmann, Vicki Cummings, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“An Ethnography of the Neolithic: Early Prehistoric Societies in Southern Scandinavia” by Christopher Tilley (1996) Amazon.com;

“Woodland in the Neolithic of Northern Europe: The Forest as Ancestor” by Gordon Noble (2017) Amazon.com;

“Paths Towards a New World: Neolithic Sweden” by Mats Larsson and Geoffrey Lemdahl (2014) Amazon.com;

“Monuments in the Making: Raising the Great Dolmens in Early Neolithic Northern Europe” by Vicki Cummings and Colin Richards (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings” by Jean Manco (2016) Amazon.com;

“Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: Relations and Descent” by Alasdair Whittle, Joshua Pollard (2023) Amazon.com;

“Seeking the First Farmers in Western Sjælland, Denmark: The Archaeology of the Transition to Agriculture in Northern Europe” by T. Douglas Price (2022) Amazon.com;

“Foragers and Farmers: Population Interaction and Agricultural Expansion in Prehistoric Europe” by Susan A. Gregg (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe (Princeton Legacy Library)” by Albert J. Ammerman and L L Cavalli-sforza (2016) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe” by Chris Fowler, Jan Harding, Daniela Hofmann (2015) Amazon.com;

“Northern Archaeology and Cosmology: A Relational View” by Vesa-Pekka Herva, Antti Lahelma Amazon.com;

“Neolithic Shamanism: Spirit Work in the Norse Tradition” by Raven Kaldera (2012) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Northern Europe” by H.R. Ellis Davidson (1965) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Rock Art in Scandinavia: Agency and Environmental Change” by Courtney Nimura (2015) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Rock Art in Iberia and Scandinavia: Words, Warriors, and Long-distance Metal Trade” by Johan Ling, Marta Díaz-Guardamino, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“In the Darkest of Days: Exploring Human Sacrifice and Value in Southern Scandinavian Prehistory” by Matthew J. Walsh , Sean O'Neill, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Seaways to Complexity: A Study of Sociopolitical Organisation Along the Coast of Northwestern Scandinavia in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age” by Austvoll and Knut Ivar (2020) Amazon.com;

“Organizing Bronze Age Societies: The Mediterranean, Central Europe, and Scandanavia Compared” by Timothy Earle, Kristian Kristiansen Amazon.com;

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

First Farmers in Scandinavia

During the 5th millennium B.C., the Ertebølle people learned pottery from neighbouring tribes in the south, who had begun to cultivate the land and keep animals. They too started to cultivate the land, and by 3000 B.C. they became part of the megalithic Funnelbeaker culture. During the 4th millennium B.C., these Funnelbeaker tribes expanded into Sweden up to Uppland. The Nøstvet and Lihult tribes learnt new technology from the advancing farmers (but not agriculture) and became the Pitted Ware cultures towards the end of the 4th millennium B.C.. These Pitted Ware tribes halted the advance of the farmers and pushed them south into southwestern Sweden, but some say that the farmers were not killed or chased away, but that they voluntarily joined the Pitted Ware culture and became part of them. At least one settlement appears to be mixed, the Alvastra pile-dwelling. [Source: Wikipedia]

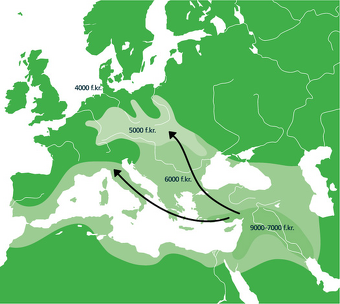

Farming started in Denmark and southern Sweden about 6,000 years ago, According to studies settlers from more developed regions of Central Europe moved to Denmark and Sweden, where they introduced advanced farming practices. They brought knowledge and agricultural experience with them, which they shared with the local hunter-gatherers over the next 300 years, transforming them into a well-developed agrarian society. [Source: Kristian Sjøgren, Science Nordic, August 17, 2015]

See Separate Article: SPREAD OF AGRICULTURE WITHIN EUROPE europe.factsanddetails.com

Hunter Gatherers Versus Farmers in Mesolithic Scandinavia

In 2015, New York University reported: “According to a team of researchers, northern Europeans in the Neolithic period initially rejected the practice of farming, which was otherwise spreading throughout the continent. Their findings offer a new wrinkle in the history of a major economic revolution that moved civilizations away from foraging and hunting as a means for survival. “This discovery goes beyond farming,” explains Solange Rigaud, the study’s lead author and a researcher at the Center for International Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (CIRHUS) in New York City. “It also reveals two different cultural trajectories that took place in Europe thousands of years ago, with southern and central regions advancing in many ways and northern regions maintaining their traditions.” [Source: New York University, April 8, 2015]

Lars Larsson, a professor emeritus of archaeology at Lund University, told National Geographic that . Skateholm and other late Mesolithic burial sites in the region along the southern Scandinavian coastline hold particular interest to archaeologists as they reveal communities of hunter-gatherers that continued to flourish for nearly a thousand years after Neolithic farmers brought agriculture into mainland Europe. [Source: Kristin Romey, National Geographic, November 12, 2019]

Kristin Romey wrote in National Geographic: It appears that geographical isolation wasn’t the reason for the late arrival of farming in Scandinavia, says Larsson, pointing to grave goods found at Skateholm that suggest trade contacts with agricultural communities on the European mainland. Rather, it was a choice. “People tend to think of hunter-gathers as uncivilized humans,” Larsson says, “but why would they transition to agriculture when they had a great situation with hunting and gathering and fishing?”

6,000-Year-Old Baltic Cooking Pots Show Gradual Transition to Agriculture

Ceramic pots excavated at sites dated to 4,000 years B.C. tell a story of some lingering hunter-gatherer ways in the Baltic regions of Northwest Europe. AZERTAC reported: “Once a fisherman, always a fisherman, one might say. This could have been the sentiment of the people who lived 6,000 years ago in what is today the Western Baltic regions of Northern Europe. Based on a study recently performed by a team of researchers led by Oliver Craig of the University of York and Carl Heron of the University of Bradford, hunter-gatherer humans here may have experienced a gradual rather than a rapid transition to agriculture. [Source:AZERTAC, October 27, 2011 ~\~]

“The researchers analyzed cooking residues preserved in 133 ceramic vessels from the Western Baltic regions of Northern Europe to determine if the residues originated from terrestrial food sources, or marine and freshwater organisms. The vessels were chosen from 15 sites dated to approximately 4,000 B.C., the time corresponding to the first evidence in the region indicating domestication of animals and plants (agriculture and animal husbandry). The evidence included samples obtained from a 6,000-year-old submerged settlement site excavated by the Archäologisches Landesmuseum in Schleswig off the Baltic coast of Northern Germany. Of the inland sites, about 28 percent of the pots showed residues from aquatic organisms, likely freshwater fish. Of the sites located in coastal areas, one-fifth of the pots showed biochemical traces of aquatic organisms, along with fats and oils normally not present in terrestrial plants and animals. ~\~

“The study results suggest that fish and other aquatic resources continued to be significantly exploited even after the advent of farming and domestication. Says Craig: "This research provides clear evidence people across the Western Baltic continued to exploit marine and freshwater resources despite the arrival of domesticated animals and plants. Although farming was introduced rapidly across this region, it may not have caused such a dramatic shift from hunter-gatherer life as we previously thought." ~\~

First Scandinavian Farmers Far More Advanced Than Previously Thought

The first farmers in Denmark and Sweden knew how to rear cattle – suggesting they knew much more about farming than previously thought, shows new research. In 2015 researchers from England studied cow teeth dated to 3,950 B.C. According to Science Nordic, The teeth show that the early farmers had mastered the cumbersome task of calving at different times of the year, so that milk was available all year round. "It’s very interesting that the farmers of the period were able to manipulate the calving seasons, so all the calves did not come in the spring. This is very hard to do, and would not have taken place if the farmers had not intended to do it,” says Kurt Gron, a researcher from the Department of Archaeology at Durham University, UK, and lead-author on the study. “This means that the earliest farmers were highly skilled from the beginning of the Neolithic period, which suggests immigrants were instrumental in bringing pastoral agriculture to the region," he says. The new results are published in PLOS One. [Source: Kristian Sjøgren, Science Nordic, August 17, 2015]

Until now, most researchers believed that early farming was primitive because the farmers held on to many of their hunter-gatherer traditions. Lasse Sørensen, a postdoc at the National Museum of Denmark who studies the transition of early Scandinavian society from hunter-gatherers to a culture dominated by farming, said: "We know that the first farmers had cows, but we do not know anything about how they managed them, and how much they still had to rely on their ancient hunter-gatherer traditions to hunt and fish. This study points to a very advanced agriculture, and it gives us a whole new understanding of everyday life in a very interesting transition period in Scandinavian history."

According to Archaeology magazine: Detailed analysis of wheat and barley grains from the Stone Age site of Karleby, Sweden have provided evidence of the use of fertilizer 5,000 years ago. The grains possessed a ratio of nitrogen isotopes suggesting the people of Karleby were supplementing their soil, probably with animal manure. Further analysis will look to see what kinds of weeds grew there — another potential indication of the presence of fertilizer. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, September-October 2013]

First Scandinavian Farmers Herded Cattle

In the study mentioned above, according to Science Nordic,, researchers analysed the oxygen isotopes in the teeth of prehistoric cattle from Almhov, in south Sweden. The isotopes are incorporated into teeth when the young cattle drink water and the chemical signal is then preserved. Since the isotopes in their drinking water vary over the course of a year, analysing the isotopes in the cows’ teeth can tell the researchers which season the cow was born in. “This comparison allowed us to conclude that cattle were manipulated by farmers to give birth in multiple seasons,” says Gron. [Source: Kristian Sjøgren, Science Nordic, August 17, 2015]

Calving in different seasons meant that farmers had access to milk all year round. According to Sørensen, this means that quite early in the Neolithic period farmers already had the techniques to make milk into yogurt or cheese. Otherwise, why would they produce milk all year round? They must also have been able to plan and collect food for the cattle to last the winter -- a time when the young calves were especially vulnerable.

All these things required buildings, tools, and skills that Danish hunter-gatherers were not able to either invent themselves or learn from others in such a short period. "It is a giant leap from hunter-gathering to farming, and it is so advanced that one cannot imagine that hunter-gatherers could have learned the necessary skills from newcomers or by themselves for that matter,” says Sørensen.

“It takes many generations to master these techniques so these farmers must have been outsiders. Their presence has spread over the centuries and become integrated with the local populations of hunter-gatherers, who would have had to spend a lot of time learning about the agricultural techniques and the farming lifestyle," he says.

4,000-Year-Old Tomb Found in Norway Offers Hints About Scandinavia’s First Farmers

A 4,000-year-old stone-lined tomb discovered during construction work in Norway may provide new clues about the first farmers who settled the region, archaeologists say. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: Since April 2023, researchers from the University Museum of Bergen have been excavating at the site of a new hotel in Selje, on the North Sea coast of southwestern Norway. So far, they have found traces of prehistoric dwellings and trash heaps full of animal bones, along with a stone tool called a blade sickle and tiny shell beads. But the most unique find is a large stone-lined tomb that held the skeletons of at least five people. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, November 17, 2023]

The burial, which archaeologists call a cist tomb, has been carbon dated to between 2140 and 2000 B.C., or the end of the Neolithic period. Measuring about 10 feet by 5 feet (3 meters by 1.5 m) and nearly 3 feet (1 m) tall, the tomb has two chambers with evidence of burials, including the remains of an elderly man with arthritis, a 2-year-old toddler and a young woman. Additional clustered bones suggest two other individuals' remains had been moved aside to bury new people.

While humans invented agriculture around 12,000 years ago in the Middle East, the technique was slow to reach Norway, where people spent millennia living a more nomadic hunting and fishing lifestyle. Two big areas of interest in Norwegian archaeology are how the idea of agriculture took hold and who the earliest farmers were. The Late Neolithic date of the burial along with the presence of a blade sickle, which may have been used to harvest grain, provides strong evidence that Selje was settled by some of the first farmers in western Norway. "The Selje cist, with its amount of bones, gives [us] a unique opportunity to look into the first groups of individuals who became farmers, as it is "the first of its kind on the west coast of Norway," Yvonne Dahl, a member of the University of Bergen archaeology team, told Live Science in an email.

During the Late Neolithic period, people in southwestern Norway typically buried their dead in rock shelters. But in the eastern part of Norway, where people were already practicing agriculture, cist graves like the one at Selje are much more common. Archaeologists have long assumed that the stone cist funeral tradition originated on the Jutland peninsula of Denmark before farming communities brought it to Sweden and Norway. Planned DNA testing of the Selje skeletons may be able to confirm whether these people migrated to the west with farming knowledge gained from the east, or whether they are a local group of people who chose a farming life. The future tests should reveal whether, as expected, the people in the tomb are biologically related to one another. Even though Selje is located on the coast, where the sea in winter makes traveling nearly impossible, "the site is clearly a meeting point for people," Dahl said. "Widespread exchange of both people, ideas, and goods must have been the case during those many thousands of years."

Farmers Kill Off Hunter-Gatherers and Pastoralists Kill Of Farmers in Neolithic Denmark

Two waves of mass death struck Neolthic Denmark, with farmers wiping out hunter-gatherers shortly after the first farmers arrived in the region around 5,900 years ago and immigrants of Eastern Steppe wiping out the farmers about 4,850 years ago, according to a DNA analysis of prehistoric human remains, according to one of four studies published together February 10, 2024 in the journal Nature. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science February 16, 2024]

"This transition has previously been presented as peaceful. However, our study indicates the opposite," study co-researcher Anne Birgitte Nielsen, a geology researcher and head of the Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory at Lund University in Sweden, said in a statement. "In addition to violent death, it is likely that new pathogens from livestock finished off many gatherers."

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science; To investigate Denmark's population turnovers, the researchers looked at DNA sampled from 100 skeletons from the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, representing a span of 7,300 years. The team also looked at isotopes, or variations of elements, in the deceased's remains, which shed light on their diets and where they lived over time.

The team found that people that belonged to the region's Mesolithic cultures — the Maglemose, Kongemose and Ertebølle — were related to other Western European hunter-gatherers. And while these groups' genetic makeup stayed fairly constant from 10,500 to 5,900 years ago, that changed when Neolithic farmers with Anatolian-related (modern-day Turkey) ancestry arrived in Denmark.

The farmers, which are associated with the Funnel Beaker culture, lived there for about 1,000 years. The study found that the people behind the Funnel Beaker culture, which is known for its funnel-shaped ceramics, "had already mixed with western hunter-gatherers before arriving in Denmark," Eva-Maria Geigl, head of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research, told Live Science in an email. Geigl, who is also a group leader of the paleogenomic group at the Institut Jacques Monod in Paris, was not involved in the study.

A few individuals in the study who lived during the Neolithic-Mesolithic transition had hunter-gatherer roots but had "adopted the culture and diet of the immigrant farmers," the researchers concluded. "Thus, individuals with hunter-gatherer ancestry persisted for decades and perhaps centuries after the arrival of farming groups in Denmark, although they have left only a minor genomic imprint on the population of the subsequent centuries," the team wrote in the study.

About 4,850 years ago, another population took over Scandinavia: a mix between nonlocal Neolithic farmers and pastoralists from the steppe. The pastoralists' genetic roots were associated primarily with the Yamnaya, a population of seminomadic livestock herders who had tamed animals, kept domestic cattle, and used horses and carts to move across the continent, according to the statement. In Denmark, the pastoralist-farmer population gave rise to the Single Grave culture, which was named from the thousands of single graves marked with low mounds. Again, it's likely that violence and new pathogens wiped out the region's then-inhabitants: the farmers who had previously wiped out the hunter-gatherers. Once the people behind the Single Grave culture arrived, "there was also a rapid population turnover, with virtually no descendants from the predecessors," Nielsen said. In the study, the team noted that the people associated with the Single Grave culture had "an ancestry profile more similar to present-day Danes."

What happened in prehistoric Denmark is similar to other places in Scandinavia. "We don't have as much DNA material from Sweden, but what [DNA] there is points to a similar course of events," Nielsen said. "In other words, many Swedes are to a great extent also descendants of these semi-nomads."

Bronze Age Scandinavia

It is not known what language these early Scandinavians spoke, but towards the end of the 3rd millennium B.C., they were overrun by tribes of the Battle-Axe culture that many scholars think spoke Proto-Indo-European and probably provided the language that was the ancestor of the modern Scandinavian languages. They were cattle herders and brought metallurgy to southern Scandinavia. This coincided with the introduction of long barrows, causewayed enclosures, two-aisled houses. [Source: Wikipedia]

Even though Scandinavians joined the European Bronze Age cultures fairly late through trade a wide variety of objects from far outside the region, Scandinavian sites present rich and well-preserved objects made of wool, wood and imported Central European bronze and gold as well as objects from Mycenaean Greece, the Villanovan Culture in Italu, Phoenicia and Ancient Egypt. Several petroglyphs depict ships, and the large stone formations known as stone ships indicate that shipping played an important role in the culture. Several petroglyphs depict ships which could possibly be Mediterranean.

The Nordic Bronze Age was characterized by a warm climate comparable to that of the Mediterranean which permitted a relatively dense population, but it ended with a climate change consisting of deteriorating, wetter and colder climate. It seems very likely that the climate pushed the Germanic tribes southwards into continental Europe. During this time there was Scandinavian influence in Eastern Europe. A thousand years later, numerous East Germanic tribes including Burgundians, Goths and Lombards, that claimed Scandinavian origins.

2,700-Year-Old Petroglyphs in Sweden Depict Ships, Carts, People and Animals

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: On a steep rock face in western Sweden, researchers uncovered a fascinating find: around 40 petroglyphs — depicting ships, people and animal figures — dating back around 2,700 years. The petroglyphs were carved on a granite rock face that was once part of an island, meaning people would have had to make the carvings while standing on a boat, or from a platform constructed on ice, said Martin Östholm, a project manager with the Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän's Rock Carvings who is one of the archaeologists who discovered the petroglyphs, told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, May 30, 2023]

Bohuslän is already known for its rock carvings, including Bronze Age art made at Tanum, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) site. The team was looking for new petroglyphs in the area when they came across the moss-covered rock face. They noticed some lines on it that appeared to be human made, so they removed the moss, revealing the petroglyphs underneath. The rock face is too steep to stand on, Östholm said, so the team had to stand on a platform to do their archaeological work.

One image shows what looks like three human figures on a long boat. Underneath this there is an image of what looks like maybe two horses pulling a cart with four wheels. The biggest petroglyph shows a ship that is 13 feet (4 meters) long, Östholm said, noting that many of the petroglyphs are between about 12 and 16 inches (30 to 40 centimeters) in length.

People would have smacked hard stones against the granite rock face to create the petroglyphs, Östholm said. This action exposed a white layer underneath, making the petroglyphs highly visible, even from the mainland or passing ships. It's not certain why people created the carvings, he said, but they may have served to mark ownership.

If the petroglyphs were made within a relatively short period of time, they may tell a story, said James Dodd, a researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark and the Tanums Hällristningsmuseum's Rock Art Research Centre Underslös in Sweden. Some of the motifs — including chariots, carts and animal figures — were depicted multiple times, he noted. "On the basis of the repetition of the motifs, it is possible that this collection of figures forms a narrative," Dodd told Live Science. Studies of other petroglyphs in the region have suggested that, in some cases, they may have been used in this way, but the exact meaning in this case is uncertain, he added. The petroglyphs were discovered in early May 2023, and research is ongoing, Östholm said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024