Home | Category: Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Humans / First Modern Humans / Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Human

EUROPE WHEN IT WAS SHARED BY HUMANS AND NEANDERTHALS

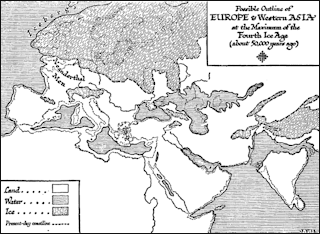

land covered by ice and land bridges during the last ice age

Around 45,000 to 40,000 years ago, modern humans arrived in Europe in significant numbers and relatively quickly expanded throughout the continent. For about 10,000 years they shared the region with Neanderthals, who were eventually, driven to extinction about 30,000 years ago. We know from genetic evidence that there was some interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals. It also appears there were some technology transfers in the form of stone tool types. But the extent of the interaction and relations between the two species is widely debated by paleontologist and human orgins scientists. A key element of the discussion is the sophistication of Neanderthals, namely were they capable of artistic expression and did they have the ability to make complex stone tools. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Neanderthals and modern humans overlapped in Europe perhaps as long for about 15,000 years — between 45,000 years ago, when modern humans entered Europe in large numbers, and 30,000 years ago, when Neanderthals became extinct. They overlapped in a general area but shared such a large area they probably did run into each other much.

Neanderthals lived primarily in northern Europe and modern men, which were better adapted for warm climates, lived around the Mediterranean. There is evidence though that they coexisted in France around 54,000 years ago, in Germany 45,000 years ago and in Spain around 32,000 years ago. Neanderthals and Homo sapiens overlapped for thousands of years in Israel and appeared to live and hunt in similar manners, without one species having an edge over the other. Then suddenly around 50,000 years ago modern human began using fine blades and projectile weapons more advanced than the hand-held axes used by Neanderthals.

See Separate Article: NEANDERTHALS AND HUMANS: INTERACTIONS, EXCHANGES, TOOLS, LIVING SIDE BY SIDE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Earliest Europeans: A Year in the Life: Survival Strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic (Oxbow Insights in Archaeology) by Robert Hosfield (2020) Amazon.com;

“Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic by Margherita Mussi Amazon.com;

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“Cro-Magnon: How the Ice Age Gave Birth to the First Modern Humans” by Brian Fagan (2011) Amazon.com;

“Cro-Magnon: The Story of the Last Ice Age People of Europe” (2023)

by Trenton W. Holliday Amazon.com;

“The Paleolithic Revolution (The First Humans and Early Civilizations)” by Paula Johanson (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Paleolithic Technologies (Routledge Studies in Archaeology)”

by Steven L. Kuhn Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics” by Jorge Martínez-Laso, Eduardo Gómez-Casado (2000) Amazon.com;

“The British Palaeolithic: Human Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World” by Paul Pettitt, Mark White Amazon.com;

“Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene—Holocene Transition” by Lawrence Guy Straus, Berit Valentin Eriksen (1996) Amazon.com

“Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age” by Erella Hovers, Steven Kuhn (2006) Amazon.com;

Ice Ages

Neanderthals and early modern humans lived at a time when Ice Ages were shaping the climate and landscape of the places they lived in Europe and elsewhere. I Ice Ages are periods of time when huge continental glaciers (sheets of ice) have crept down from the Arctic and covered much of North America and Europe. The Pleistocene Age, which lasted from 2.6-2.3 million to 11,700 years ago, is regarded as an ice age, within which there were glacial periods, which many people think of ice ages, when glaciers grew and shrunk during different periods. The first Ice Age glaciers began appearing long ago. Large glaciers have covered landmasses for millions of years at different times before the Pleistocene Age.

There has been at least five major ice ages. The first one occurred about 2 billion years ago and lasted about 300 million years. The most recent one started about 2.6 million years ago, and technically is still going on. Denise Su wrote: When most people talk about the “ice age,” they are usually referring to the last glacial period, which began about 115,000 years ago and ended about 11,000 years ago with the start of the current interglacial period. During that time, the planet was much cooler than it is now. At its peak, when ice sheets covered most of North America, the average global temperature was about 46 degrees Fahrenheit (8 degrees Celsius). That’s 11 degrees F (6 degrees C) cooler than the global annual average today. That difference might not sound like a lot, but it resulted in most of North America and Eurasia being covered in ice sheets. Earth was also much drier, and sea level was much lower, since most of the Earth’s water was trapped in the ice sheets. Steppes, or dry grassy plains, were common. So were savannas, or warmer grassy plains, and deserts. [Source: Denise Su, Associate Professor, Arizona State University, The Conversation, June 27, 2022]

The four main glacial periods ("ice ages") are (the names refer to the southern limit of the glaciers in Europe and, in parentheses, the United States): 1) the Günz (known in the U.S. as the Nebraskan) occurred around 2 million years ago); 2) the Mindel (known in the U.S. as the Kansan) occurred around 1.25 million years ago); 3) the Riss (known in the U.S. as the Illinoisian) occurred around 500,000 years ago); and 4) the Würm (known in the U.S. as the Wisconsin) occurred around 100,000 years ago).

See Separate Article ICE AGES AND ICE AGE GLACIERS factsanddetails.com

Last Glacial Period (Ice Age)

Europe's 4th Ice Age Around 125,000 years ago, in the middle of major warm, interglacial period, sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today. Areas of Africa, the Middle East and West Asia that are desert today were covered by tropical deciduous forests and savanna dotted with numerous lakes.

After that the climate began getting colder. By around 100,000 years a new Ice Age had begun. About 65,000 years, in the middle of the ice age, glaciers covered nearly 17 million square miles, including much of northern Europe and Canada, and sea levels were more than 400 feet lower that they are today. Many islands and land masses that are now separated by ocean water were connected by land bridges. Among the land masses that were connected were Australia and Indonesia, and Alaska and Siberia.

Around 40,000 years ago glaciers began to melt. At that time they still covered most of Britain and extended into Europe as far south as Germany. By around 17,000 years ago they had retreated from Germany. Around 13,000 they had retreated from Sweden. The Ice Age officially ended about 10,000 years ago.

The landscape of Europe was covered by ice. But it was also altered in other ways not directly related to the ice. As the glaciers moved southward, for example, forests were replaced with tundra and steppe.

During the last ice age Europe was covered mostly by open steppe which is an ideal habitat for grazing animals like horses, rhinos, deer, mammoth, reindeer and bison. Vast herds of these animals, fed on steppe grasses, roamed across Europe and Asia. As the Ice Ages ended and the climate warmed up, the habitant for the large animals herds declined as the grasslands were replaced by birch and evergreen forests.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “Among ecologists, the prevailing view of Europe in its natural, which is to say pre-agrarian, state is that it was heavily forested. (The continent’s last stands of old-growth forest are found on the border of Poland and Belarus, in the Bialowieza Forest, which the author Alan Weisman has described as a “relic of what once stretched east to Siberia and west to Ireland.”)” An ecologist named Frans “Vera argues that, even before Europeans figured out how to farm, the continent was more of a parklike landscape, with large expanses of open meadow. It was kept this way, he maintains, by large herds of herbivores—aurochs, red deer, tarpans, and European bison. (The bison, also known as wisents, were hunted nearly to extinction by the late eighteen-hundreds.) [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker , December 24 & 31, 2012 ||*||]

“Vera has written up his argument in a dense, five-hundred-page treatise that has received a good deal of attention from European naturalists, not all of it favorable. A botany professor at Dublin’s Trinity College, Fraser Mitchell, has written that an analysis of ancient pollen “forces the rejection of Vera’s hypothesis.” Vera, for his part, rejects the rejection, arguing that, precisely because they ate so much grass, the aurochs and the wisents skewed the pollen record. “That is a scientific debate that is still going on,” he told me.”

“Special Places” in Northern Europe Chosen Based on Food Availability

Research led by the University of Southampton has found that early humans were driven by a need for nutrient-rich food to select ‘special places’ in northern Europe as their main habitat. Evidence of their activity at these sites comes in the form of hundreds of stone tools, including handaxes. According to the University of Southampton: “A study led by physical geographer at Southampton Professor Tony Brown, in collaboration with archaeologist Dr Laura Basell at Queen’s University Belfast, has found that sites popular with our early human ancestors, were abundant in foods containing nutrients vital for a balanced diet. The most important sites, dating between 500,000 to 100,000 years ago were based at the lower end of river valleys, providing ideal bases for early hominins – early humans who lived before Homo sapiens (us). [Source: University of Southampton, December 10, 2013]

“Professor Brown says: “Our research suggests that floodplain zones closer to the mouth of a river provided the ideal place for hominin activity, rather than forested slopes, plateaus or estuaries. The landscape in these locations tended to be richer in the nutrients critical for maintaining population health and maximising reproductive success.”

“The researchers began by identifying Palaeolithic sites in southern England and northern France where high concentrations of handaxes had been excavated –for example at Dunbridge in Hampshire, Swanscombe near Dartford and the Somme Valley in France. They found there were fewer than 25 sites where 500 handaxes or more were discovered. The high concentration of these artefacts suggests significant activity at the sites and that they were regularly used by early hominins.

“Professor Brown and his colleagues then compiled a database of plants and animals known to exist in the Pleistocene epoch (a period between 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) to establish a potential list of nutrient resources in the landscape and an estimation of the possible diet. This showed that an abundance of nutritious foods were available and suggests this was likely to have been the dominant factor driving early humans to focus on these sites in the lower reaches of river valleys, close to the upper tidal limit of rivers.

“Over 50 nutrients are needed to sustain human life. In particular, it would have been essential for early humans to find sources of protein, fats, carbohydrates, folic acid and vitamin C. The researchers suggest vitamins and protein may have come from sources such as raw liver, eggs, fish and plants, including watercress (which grows year round). Fats in particular, may have come from bone marrow, beaver tails and highly nutritious eels.

“The nutritional diversity of these sites allowed hominins to colonise the Atlantic fringe of north west Europe during warm periods of the Pleistocene. These sites permitted the repeated occupation of this marginal area from warmer climate zones further south. Professor Brown comments: “We can speculate that these types of locations were seen as ‘healthy’ or ‘good’ places to live which hominins revisited on a regular basis. If this is the case, the sites may have provided ‘nodal points’ or base camps along nutrient-rich route-ways through the Palaeolithic landscape, allowing early humans to explore northwards to more challenging environments.”“

Early human sites in Europe

Life of Modern Humans in Germany 45,000 Years Ago

The modern humans that arrived in a northern Europe 45,000 years lived in an environment that was far colder than today, more resembling modern-day Siberia or northern Scandinavia, the researchers said. Based on research of the Ranis site in Germany, they lived in small, mobile groups, only briefly staying in the cave where they ate meat from reindeer, woolly rhinoceros, horses and other animals they caught. "How did these people from Africa come up with the idea of heading towards such extreme temperatures?" Hublin said. In any case, the humans proved they had "the technical capacity and adaptability necessary to live in a hostile environment", he added. It had previously been thought that humans were not able to handle such cold until thousands of years later. [Source: Juliette Collen, AFP, February 1, 2024]

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: This site is best known for some finely flaked, leaf-shaped stone tool blades called leaf points. The leaf points are similar to stone tools that have been uncovered at several sites in the United Kingdom, Poland, Moravia, and elsewhere in Germany. Archaeologists believe that they were all produced by the same culture known as the Lincombian — Ranisian — Jerzmanowician (LRJ) culture. However, without recognizable bones to indicate who crafted the tools found there, it was not clear if Neanderthals or Homo sapiens made them. In order to know if a Neanderthal or Homo sapien crafted the tools, it would take some DNA. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, February 1, 2024]

Some human remains were found. "We confirmed that the skeletal fragments belonged to Homo sapiens. Interestingly, several fragments shared the same mitochondrial DNA sequences — even fragments from different excavations," University of California, Berkeley research fellow Elena Zavala said. "This indicates that the fragments belonged to the same individual or their maternal relatives, linking these new finds with the ones from decades ago."

These bone fragments were initially identified as human through analysis of bone proteins by study co-author Dorothea Mylopotamitaki, a doctoral student at the Collège de France. The team compared the Ranis mitochondrial DNA sequences with other mitochondrial DNA sequences from human remains at other paleolithic sites in Europe. They used this data to construct a family tree of early Homo sapiens across Europe. They found that all but 13 fragments from the Ranis cave were similar to one another. They also resembled mitochondrial DNA from a 43,000-year-old skull of a woman found in a cave in the Czech Republic. The DNA revealed that Homo sapiens were present at least in this part of Germany, not just Neanderthals.

The cave excavation also found traces of DNA from horses, cave bears, woolly rhinoceroses, and reindeer, which indicates that the area had a colder climate similar to the tundra of Siberia and northern Scandinavia today. It also indicates that the human diet at the time was based on these large land animals and that early groups of Homo sapiens dispersing across Eurasia could adapt to harsh changes in climate conditions. “Zooarchaeological analysis shows that the Ranis cave was used intermittently by denning hyenas, hibernating cave bears, and small groups of humans,” Geoff Smith, a study co-author and zooarchaeologist from the University of Kent and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said. “While these humans only used the cave for short periods of time, they consumed meat from a range of animals. Although the bones were broken into smaller pieces, they were exceptionally well preserved and allowed us to apply the latest cutting-edge methods from archaeological science, proteomics and genetics.”

Modern Humans and Neanderthals in Germany Together 45,000 Years Ago

The modern humans in Germany means they could have lived there side by side with Neanderthals, scientists said. Juliette Collen of AFP wrote: The discovery could rewrite the story of how the species populated Europe — and how it came to replace the Neanderthals, who mysteriously went extinct just a few thousand years after humans arrived. When the two co-existed in Europe, there was a "replacement phenomenon" between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic periods, French paleoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin, who led the new research, told AFP. [Source: Juliette Collen, AFP, February 1, 2024]

"For a long time we have thought of a great wave of Homo sapiens that swept across Europe and rapidly absorbed the Neanderthals towards the end of these transitional cultures around 40,000 years ago," Hublin said. But the latest discovery suggests that humans populated the continent over repeated smaller excursions — and earlier than had previously been assumed.

This means there was even more time for modern humans to have lived side-by-side with their Neanderthal cousins. PA Media reported: The researchers said their discovery also challenges the view that Neanderthals disappeared from northern Europe long before the arrival of modern humans, adding that this hypothesis “can now be rejected”. The scientists also said their work adds to existing genetic evidence that humans and Neanderthals lived side by side and occasionally interbred. Hublin said: “It turns out that stone artefacts that were thought to be produced by Neanderthals were in fact part of the early Homo sapiens tool kit.This fundamentally changes our previous knowledge about this time period: Homo sapiens reached northwestern Europe long before Neanderthal disappearance in southwestern Europe.”[Source: Nilima Marshall, PA Media, February 1, 2024]

John Hawks, a University of Wisconsin-Madison paleoanthropologist said the study helps solidify the theory that patches of different human cultures were developing as Neanderthals neared their end. “These groups are exploring. They’re going to new places. They live there for a while. They have lifestyles that are different,” he said of the early humans. “They’re comfortable moving into areas where there were Neanderthals.” “These early modern people seem to have mastered or put together a cultural package that let them succeed at northern latitudes better than Neanderthals had done,” Hawks said.

The Ranis site study in Germany also suggests that the leaf point technology scientists had once attributed to Neanderthals was used by humans. “It’s a thoroughly skilled process to make those things,” Hawks said of leaf points, which are flakes of rock thinned into the shape of an olive leaf. “The fact that people invested the energy to make that beautiful thing — tells us about their social system. It tells us they were not living hand to mouth. They had time to invest.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024