Home | Category: Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Humans / Neanderthals, Denisovans and Modern Human

NEANDERTHALS AND HUMANS

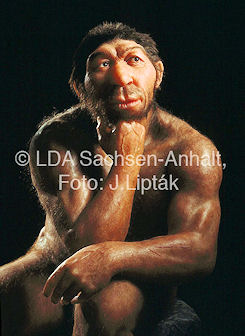

Early Modern humans were taller and narrower than Neanderthals and a had a less voluminous rib cage. Neanderthals could be as much as 15 centimeters (half a foot) shorter than modern humans. They were squatter with stubbier extremities, likely because they evolved in a colder part of the world compared to early humans, who did most of their evolution in Africa. Modern human brain cases were "higher and rounder" than those of Neanderthals. Early human brows were also much less pronounced, if not non-existent, compared to Neanderthals. CT scans reveal that human ear bones are shaped differently compared to Neanderthals. [Source: Sara Novak, Discover Magazine, April 9, 2024]

For a period of time, Neanderthals overlapped with humans and even had sex with them. Neanderthals and closely Denisovans are our closest extinct relatives. Several studies have shown that most people of Eurasian descent carry between and one and four percent of Neanderthal genes in their own genome.

Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Them and Us: How Neanderthal Predation Created Modern Humans” by Danny Vendramini (2014) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala and Camilo J. Cela-Conde (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction”

by Pat Shipman Amazon.com;

“The Smart Neanderthal: Bird catching, Cave Art, and the Cognitive Revolution”

by Clive Finlayson Amazon.com;

“Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art” by Rebecca Wragg Sykes (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science Is Rewriting Their Story”

by Dimitra Papagianni and Michael A. Morse (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind, and Body”

by Steven Mithen (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Naked Neanderthal: A New Understanding of the Human Creature” by Ludovic Slimak Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

Are Neanderthals and Modern Humans Different Species?

Are Neanderthals and modern humans the same species, different species or subspecies. The most common definition of a species — the biological species concept — defines a species as a group of individuals that can interbreed in nature and produce viable offspring. But there are exceptions to this rule such as horses and donkeys (who can breed, but their offspring, mules are steril), ligers (crosses between a lion and a tiger) and beefalo (crosses between a cow and an American bison). The later give birth to viable offsping

In 1962, a group of anthropologists, geneticists and behaviorists met in Austria to draft and vote on an evolutionary history of human relatives based on the species that had been discovered at the time. Their resulting manuscript, called "Classification and Human Evolution," placed Neanderthals under Homo sapiens as a subspecies. "And when I was in college, that's what I was taught," said Jeff Schwartz, a physical anthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh, told Live Science.. It was only later, in the 1970s and 1980s, that Neanderthals were reclassified as their own species based on new analyses, and that remains the most common designation seen today.[Source: Amanda Heidt, Live Science, April 9, 2024\

According to Live Science: But a 2010 discovery shook things up yet again: An international team of dozens of researchers published the first draft of the Neanderthal genome, based on three individuals, and compared it with that of modern humans. The authors found hints of the Neanderthal signature in the human genomes, suggesting that Neandertals mixed with modern human ancestors at least 120,000 years ago. Dozens of papers have since confirmed this and found that interbreeding occurred at multiple points in time.

"The implication is clear: Neanderthals and humans were interbreeding," Jaume Bertranpetit, an evolutionary biologist at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, told Live Science, adding that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens also interbred with another group of early hominids, the Denisovans. It's possible, then, that all three could represent different versions of the same species, he said.

Bertranpetit pointed to modern humans as an example. People around the world have noticeable differences in stature or skin, hair and eye color, but we're remarkably similar from a genetic standpoint. The amount of genetic variation between any two individuals is only about 0.1 percent, meaning that only one base pair out of every 1,000 will be different. In comparison, the 2010 paper showed that the Neanderthal genome was 99.7 percent percent identical to that of five present-day humans. "To have big differences in morphology does not mean you need to have big differences in genetics; it just means you need some differences in specific genes," Bertranpetit said. "So this idea that they were different species doesn't make any sense to me as a geneticist."

Schwartz doesn't think the genetic evidence has necessarily settled the debate, but he has no misgivings about the rigor of the work the other groups have done. Moving forward, he advocates for an interdisciplinary approach that doesn't position genetics as the final say. "We need a holistic approach, and we can't keep pitting one discipline against another," he said. "We have to get together and figure it out."

Neanderthal and Modern Humans Side By Side

Neanderthals and modern humans overlapped in Europe perhaps as long for about 15,000 years — between 45,000 years ago, when modern humans entered Europe in large numbers, and 30,000 years ago, when Neanderthals became extinct. They overlapped in a general area but shared such a large area they probably did run into each other much.

Neanderthals and modern humans overlapped in Europe perhaps as long for about 15,000 years — between 45,000 years ago, when modern humans entered Europe in large numbers, and 30,000 years ago, when Neanderthals became extinct. They overlapped in a general area but shared such a large area they probably did run into each other much.

Neanderthals lived primarily in northern Europe and modern men, which were better adapted for warm climates, lived around the Mediterranean. There is evidence though that they coexisted in France around 54,000 years ago, in Germany 45,000 years ago and in Spain around 32,000 years ago. Neanderthals and Homo sapiens overlapped for thousands of years in Israel and appeared to live and hunt in similar manners, without one species having an edge over the other. Then suddenly around 50,000 years ago modern human began using fine blades and projectile weapons more advanced than the hand-held axes used by Neanderthals.

Stanford anthropologist Richard Klein told National Geographic, "I think there was a mutation in the brains of a group of anatomically modern human beings living in either Africa or the Middle East. Some new neurological connections let them behave in a modern way. Maybe it permitted fully articulate speech, so they can pass on information more efficiently." Modern men migrated to Europe and the Middle East from Africa where they had evolved. They had better shelters, more efficient hearths and tailored clothing that Neanderthals didn't have.

Neanderthals and Modern Humans Intermingled in Germany 45,000 Years Ago

A genetic analysis of bone fragments from an archaeological site in central Germany shows that modern humans and Neanderthals overlapped in Europe 45,000 years ago generally to three papers published January 31, 2024 in journals Nature and Nature Ecology and Evolution. An international, multidisciplinary team of researchers studied bone fragments and stone tool blades from a site near Ranis, Germany, first explored in the 1930s, and re-excavated from 2016 to 2022. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, February 1, 2024]

Laura Baisas wrote in Popular Science: This site is best known for some finely flaked, leaf-shaped stone tool blades called leaf points. The leaf points are similar to stone tools that have been uncovered at several sites in the United Kingdom, Poland, Moravia, and elsewhere in Germany. Archaeologists believe that they were all produced by the same culture known as the Lincombian — Ranisian — Jerzmanowician (LRJ) culture. Previous dating of the Ranis site estimated that it was 40,000 years old or older. However, without recognizable bones to indicate who crafted the tools found there, it was not clear if Neanderthals or Homo sapiens made them. In order to know if a Neanderthal or Homo sapien crafted the tools, it would take some DNA.

“After removing that rock by hand, we finally uncovered the LRJ layers and even found human fossils. This came as a huge surprise, as no human fossils were known from the LRJ before, and was a reward for the hard work at the site,” Marcel Weiss, a study co-author neurophysicist at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, said.

These human remains meant that they could perform genetic analysis to see who could have made the stone tools."We confirmed that the skeletal fragments belonged to Homo sapiens. Interestingly, several fragments shared the same mitochondrial DNA sequences—even fragments from different excavations," University of California, Berkeley research fellow Elena Zavala said. "This indicates that the fragments belonged to the same individual or their maternal relatives, linking these new finds with the ones from decades ago."

These bone fragments were initially identified as human through analysis of bone proteins by study co-author Dorothea Mylopotamitaki, a doctoral student at the Collège de France. The team compared the Ranis mitochondrial DNA sequences with other mitochondrial DNA sequences from human remains at other paleolithic sites in Europe.

They used this data to construct a family tree of early Homo sapiens across Europe. They found that all but 13 fragments from the Ranis cave were similar to one another. They also resembled mitochondrial DNA from a 43,000-year-old skull of a woman found in a cave in the Czech Republic. The DNA revealed that Homo sapiens were present at least in this part of Germany, not just Neanderthals.

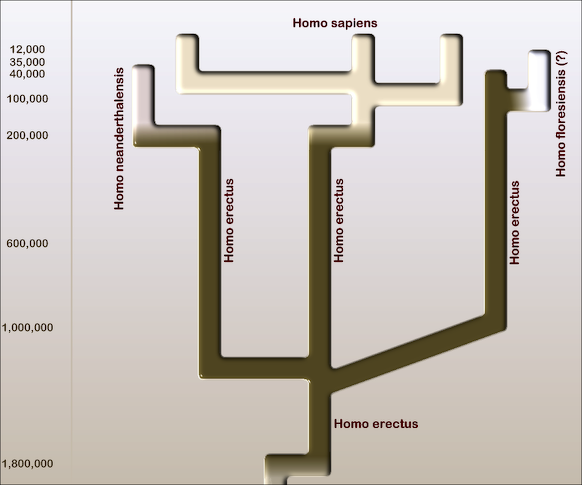

Homo splitter theory of human and Neanderthal development

Modern Humans and Neanderthals Share A Cave in France 50,000 Year Ago

In 2022, scientists announced that they had pretty firm evidence that modern humans lived in France 54,000 year ago. In an article in The Conversation they wrote: “Perched about 325 feet (100 meters) up the slopes of the Prealps in southern France, a humble rock shelter looks out over the Rhône River Valley. It’s a strategic point on the landscape, as here the Rhône flows through a narrows between two mountain ranges.[Source: 1) Jason E. Lewis, Lecturer of Anthropology and Assistant Director of the Turkana Basin Institute, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York); 2) Ludovic Slimak, CNRS Permanent Member, Université Toulouse — Jean Jaurès; 3) Clément Zanolli, Paleoanthropologist, Université de Bordeaux, and 4) Laure Metz, Archaeologist at Aix-Marseille Université and Affiliated Researcher in Anthropology, University of ConnecticutThe Conversation, February 10, 2022]

“In the journal Science Advances, we describe our discovery of evidence that modern humans lived 54,000 years ago at Mandrin. That’s some 10 millennia earlier than our species was previously thought to be in Europe and over a thousand miles west (1,700 kilometers) from the next-oldest known site, in Bulgaria. And fascinatingly, Neanderthals appear to have used the cave both before and after the modern human occupation.

Throughout the 45,000 to 55,000-year-old layers of Grotte Mandrin in France there are fragments of the shelter walls and roof that have fallen off and been buried with the fossils and artifacts. Four scientists wrote in The Conversation:“When Neanderthals and modern humans made fires in the site, the smoke would leave a layer of soot on those surfaces. Then the following season a thin layer of calcium carbonate called speleothem would cover it over. This cycle was repeated over and over. [Source: 1) Jason E. Lewis, Lecturer of Anthropology and Assistant Director of the Turkana Basin Institute, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York); 2) Ludovic Slimak, CNRS Permanent Member, Université Toulouse — Jean Jaurès; 3) Clément Zanolli, Paleoanthropologist, Université de Bordeaux, and 4) Laure Metz, Archaeologist at Aix-Marseille Université and Affiliated Researcher in Anthropology, University of ConnecticutThe Conversation, February 10, 2022]

“We first discovered these sooted vault fragments in 2006, and the team recovered thousands, year after year, in every archaeological layer of Mandrin. A decade of work by team member Ségolène Vandevelde has shown that these patterns can be read like tree rings to tell us with what frequency and duration the groups visited the site, demonstrating that human groups came to Mandrin some 500 times over 80,000 years.Vandevelde was then able to determine how much time separated the last Neanderthal fire from the first modern human fire in the cave, showing that it was only a maximum of a year between Neanderthals using Grotte Mandrin and modern humans moving in. After the modern humans occupied Mandrin annually for some 40 years, one or two generations, they disappeared just as quickly and mysteriously as they had appeared. Neanderthals then regularly reoccupied Mandrin over the following 12,000 years.

Ancient Teeth from Jersey Hint at Neanderthal-Modern-Human Mixing

Prehistoric teeth unearthed at a site on Jersey island between Britain and France reveal signs of interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans. The BBC reported: “UK experts re-studied 13 teeth found between 1910 and 1911 at La Cotte de St Brelade in the island's south-west. They were long regarded as being typical Neanderthal specimens, but the reassessment also uncovered features characteristic of modern human teeth. The teeth may represent some of the last known Neanderthal remains.[Source: BBC, February 1, 2021]

“The teeth were discovered on a small granite ledge at the cave site. They were previously thought to belong to a single Neanderthal individual. However, the new research found they were from at least two adults. The researchers used computed tomography (CT) scans of the teeth to study them at a level of detail that wasn't available to researchers in the past.

While all the specimens have some Neanderthal characteristics, some aspects of their shape are more typical of teeth from modern humans. This suggests these were traits that were prevalent in their population. “Research leader Prof Chris Stringer, from London's Natural History Museum, said: "Given that modern humans overlapped with Neanderthals in some parts of Europe after 45,000 years ago, the unusual features of these La Cotte individuals suggest that they could have had a dual Neanderthal-modern human ancestry."

“The human teeth are thought to be around 48,000 years old, close to the presumed Neanderthal extinction date of 30,000 to 40,000 years ago. “So, rather than going extinct in the traditional sense, were Neanderthal groups simply absorbed into incoming modern human populations? “This now needs to be a scenario that's seriously considered, alongside others, and it's going to emerge as we get more understanding of the process of genetic admixture," “Co-author Dr Matt Pope, from the Institute of Archaeology at University College London (UCL), told BBC News. “But certainly, that word 'extinct' now starts to lose its meaning where you can see multiple episodes of admixture and the retention of a significant proportion of Neanderthal DNA in humans beyond sub-Saharan Africa." The study has been published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

How Did Neanderthals and Humans Share Space

Modern humans and Neanderthals are believed to have coexisted in Europe for at least more than 5,000 years, giving them plenty of time to meet and mix and get to know one another. Associated Press reported: “Using new carbon dating techniques and mathematical models, researchers examined about 200 samples found at 40 sites from Spain to Russia, according to a study published in the journal Nature. They concluded with a high probability that pockets of Neanderthal culture survived until between 41,030 and 39,260 years ago. [Source: Associated Press, August 21, 2014]

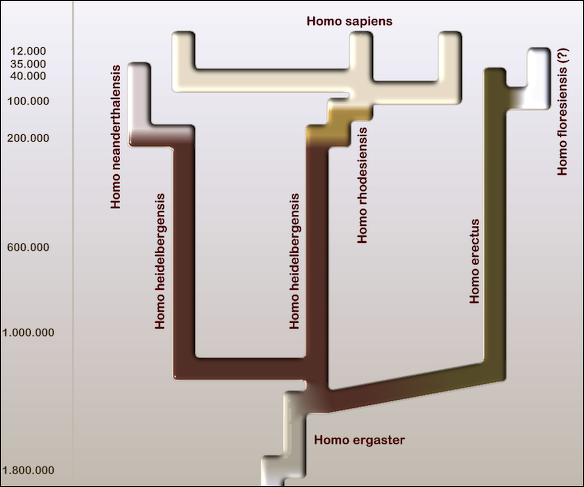

Homo lumper theory of human and Neanderthal development

“Although this puts the disappearance of Neanderthals earlier than some scientists previously thought, the findings support the idea that they lived alongside humans, who arrived in Europe about 45,000-43,000 years ago. “We believe we now have the first robust timeline that sheds new light on some of the key questions around the possible interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans,” said Thomas Higham, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford who led the study.

“While there is evidence that Neanderthal genes have survived in the DNA of today’s humans, suggesting that at least some interbreeding took place, scientists are still unclear about the extent of their contact and the reasons why Neanderthals vanished. “These new results confirm a long-suspected chronological overlap between the last Neanderthals and the first modern humans in Europe,” said Jean-Jacques Hublin, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Apart from narrowing the length of time that the two species existed alongside each other to between 2,600 and 5,400 years, Higham and his colleagues also believe they have shown that Neanderthals and humans largely kept to themselves. “What we don’t see is that there is spatial overlap [in where they settled],” said Higham. This is considered puzzling, because there is evidence that late-stage Neanderthals were culturally influenced by modern humans. Samples taken from some Neanderthal sites include artefacts that look like those introduced to Europe by humans migrating from Africa. This would point to the possibility that Neanderthals, whose name derives from a valley in western Germany, adopted certain human habits and technologies even as they were being gradually pushed out of their territory. “I think they were eventually outcompeted,” said Higham. “Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, cautioned that the study relied to a large degree on testing of stone tools, rather than bones, and these had not been conclusively linked to particular species, or hominins. “The results of this impressive dating study are clear, but the assumptions about the association of stone artefact with hominin types underlying the interpretation of the dating results will be undoubtedly rigorously tested in field – and laboratory – work over the near future,” said Roebroeks, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Such testing can now be done with a chronologically clean slate.”

Neanderthals and Humans: Living Together and Sharing DNA

Robin McKie wrote in The Guardian: “Homo sapiens and Neanderthals had a common ancestor, about 500,000 years ago, before the former evolved as a separate species – in Africa – and the latter as a different species in Europe. Then around 70,000 years ago, when modern humans emerged from Africa, we encountered the Neanderthals, most probably in the Middle East. We briefly mixed and interbred with them before we continued our slow diaspora across the planet. “In doing so, those early planetary settlers carried Neanderthal DNA with them as they spread out over the world’s four quarters. Hence its presence in all those of non-African origin. By contrast, Neanderthal DNA is absent in people of African origins because they remained in our species’s homeland [Source: Robin McKie, The Guardian, April 7, 2018]

Homo extreme splitter theory of human and Neanderthal development

Harvard University geneticist David Reich“Reich has since established that such interbreeding may have occurred on more than one occasion. More importantly, his studies show that “Neanderthals must have been more like us than we had imagined, perhaps capable of many behaviours that we typically associate with modern humans”. They would, most likely, have had language, culture and sophisticated behaviours. Hence the mutual attraction. That itself is intriguing. However, there is another key implication of Reich’s work. Previously, it had been commonplace to view human populations arising from ancestral groupings like the trunk of a great tree. “Present populations budded from past ones, which branched from a common root in Africa,” he states. “And it implies that if a population separates then it does not remix, as fusions of branches cannot occur.” |=|

“But the initial separation of the two lines of ancient humans who gave rise to Neanderthals and to Homo sapiens – and then their subsequent intermingling – shows that remixing does occur. Indeed, Reich believes it was commonplace and that the standard tree model of populations is basically wrong. Throughout our prehistory, populations have split, reformed, moved on, remixed and interbred and then moved on again. Alliances have shifted and empires have fallen in a perpetual, sliding global Game of Thrones. |=|

“An illustration is provided by the puzzling fact that Europeans and Native Americans share surprising genetic similarities. The explanation was provided by Reich who has discovered that a now nonexistent group of people, the Ancient North Eurasians, thrived around 15,000 years ago and then split into two groups. One migrated across Siberia and gave rise to the people who crossed the Bering land bridge between Asia and America and later gave rise to Native Americans. The other group headed west and contributed to Europeans. Hence the link between Europeans and Native Americans. |=|

“No physical specimen of the Ancient North Eurasian people had ever been discovered when Reich announced their existence. Instead, he based his analysis on the ghostly impact of their DNA on present-day people. However, the fossil remains of a boy, recently found near the Siberian village of Mal’ta, have since been found to have DNA that matches the genomes of Ancient North Eurasians, giving firmer physical proof of their existence. “Prior to the genome revolution, I – like most others – had assumed that the big genetic clusters of populations we see today reflect deep splits of the past. But in fact the big clusters today are themselves the result of mixtures of very different populations that existed earlier. There was never a single trunk population in the human past. It has been mixtures all the way down.” |=|

“Instead of a tree, a better metaphor would be a trellis, branching and remixing far back into the past, says Reich, whose work indicates that the idea of race is a very fluid, ephemeral concept. However, he is adamant that it is a very real one and takes issue with those geneticists who argue that there are no substantial differences in traits between populations. This is a strategy that we scientists can no longer afford and that in fact is positively harmful,” he argues. Plenty of traits show differences between populations: skin colour, susceptibility to disease, the ability to breath at high altitudes and the ability to digest starch. More to the point, uncovering these differences is only just beginning. Many more will be discovered over the decades, Reich believes. Crucially, we need to be able to debate the implications of their presence at varying levels in different populations. That is not happening at present and that has dangerous implications. If as scientists we wilfully abstain from laying out a rational framework for discussing human differences, we will leave a vacuum that will be filled by pseudoscience, an outcome that is far worse than anything we could achieve by talking openly,” says Reich. The genome revolution provides us with a shared history, he adds. “If we pay proper attention, it should give us an alternative to the evils of racism and nationalism and make us realise that we are all entitled equally to our human heritage.” |=|

Homo sapiens and Neanderthals

Exchange of Microorganisms Between Neanderthals and Sapiens

According to the University of Adelaide, based on a DNA study of dental plaque found at El Sidron cave in northern Spain: “Neanderthals, ancient and modern humans also shared several disease-causing microbes, including the bacteria that cause dental caries and gum disease. The Neandertal plaque allowed reconstruction of the oldest microbial genome yet sequenced – Methanobrevibacter oralis, a commensal that can be associated with gum disease. Remarkably, the genome sequence suggests Neandertals and humans were swapping pathogens as recently as 180,000 years ago, long after the divergence of the two species. [Source: University of Adelaide and the Spanish National Research Council, March 9, 2017 **/]

“The team also noted how rapidly the oral microbial community has altered in recent history. The composition of the oral bacterial population in Neanderthals and both ancient and modern humans correlated closely with the amount of meat in the diet, with the Spanish Neanderthals grouping with chimpanzees and our forager ancestors in Africa. In contrast, the Belgian Neanderthal bacteria were similar to early hunter gatherers, and quite close to modern humans and early farmers. **/

“The scientific investigators compared Neanderthal oral micro-biotic data with human samples from Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, African nomads, the first Neolithic farmers as well as from present-day man. “Micro-biotic information is key to learning about the host’s health. Neanderthals for example have fewer potentially pathogenic bacteria than we do. In today’s human population a link has been seen between oral micro-biotics and a spectrum of health issues such as cardiovascular problems, obesity, psoriasis, asthma, colitis and gastroesophageal reflux”, highlights CSIC researcher Carles Lalueza-Fox, who works at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (a CSIC-University of Pompeu Fabra shared centre). **/

“Furthermore, the dental plaque from the individuals at El Sidrón has also made it possible to retrieve the oldest complete microorganism genome: the ancient Methanobrevibacter oralis, which is now classified as a Neanderthal subspecies. The Neanderthal and modern human strains appear to have diverged between 112,000 and 143,000 years ago, after the two evolutionary lines split. “Today we know that crossbreeding took place on two occasions between sapiens and those Neanderthals who later lived in the Siberian region, but not with those in Asturias. If there was micro-biotic transfer between the Asturias Neanderthals and sapiens, then perhaps a cross-line existed between them, although we are yet to identify that”, concludes Lalueza Fox. **/

Interbreeding Between Neanderthals and Modern Men

In May 2010, the team lead by Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute reported that, in the process of sequencing the Neanderthal genome, it found that between 1 percent and 4 percent of the genes that people from Europe and Asia possess can be traced back to Neanderthals. This means that humans and Neanderthals mated.

The discovery was reportedly in the journal Science in article authored by Paabo, Richard Green of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and David Reich of Harvard Medical School. It was determined by analyzing genetic material collected from bones of three Neanderthals and five modern humans. Their research showed a relationship between Neanderthal and modern humans outside of Africa, with the interbreeding likely taking place in the Middle East.

Before the discovery some anthropologists argued that modern men wiped out the Neanderthals. Others theorized the two species intermingled and Neanderthals were absorbed into the more numerous modern humans. Paabo told the Times of London, “It’s cool to think that some of us have a little Neanderthal DNA in us, but for me the opportunity to search for evidence of positive selection that happened shortly after the species separated is probably the most fascinating aspect of this project.”

See Separate Article:NEANDERTHALS AND HUMANS INTERBREEDING, SEX AND OFFSPING europe.factsanddetails.com

40,000-Year-Old Hip Bone — Not Quite Human, Not Quite Neanderthal

A tiny fossil hip bone found in France surprised scientists because it didn’t appear to come form any known lineage of modern human, a July 2023 study in the journal Scientific Reports reported. The 40,000-year-old bone — a newborn's hip bone, known as an ilium — is subtly different from those found in humans alive today. It's possible that the bone comes from a group of Neanderthals and humans that were living together, the researchers said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, December 29, 2023]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: Previous research in Europe suggested that the final phase of Neanderthal culture might have been a group called the Châtelperronian. Artifacts from Châtelperronian sites, which date to about 44,500 to 41,000 years ago, extend from northern Spain to the Paris Basin. However, the Châtelperronian has inspired a great deal of controversy over the years from scientists who argued that its artifacts were actually modern human in nature. Prior work found that modern humans had made their way to Western Europe by about 42,000 years ago. In the new study, the researchers focused on a key site for investigating the identity of the Châtelperronian: the Grotte du Renne cave in Arcy-sur-Cure, about 125 miles (200 kilometers) southeast of Paris. Scientists had previously discovered several Neanderthal remains within the cave's Châtelperronian levels. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science August 22, 2023]

The scientists investigated a newborn's hip bone — an ilium, one of the three bones that make up the pelvic girdle. This bone, about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) wide, was found in a layer previously dated to about 40,680 to 42,335 years old. Scientists had found other remains there that DNA revealed were Neanderthal in origin. The paleoanthropologists compared this hip bone to the same bones in two Neanderthal babies and 32 present-day human newborns. They discovered that the Grotte du Renne fossil clearly differed from Neanderthal bones. It also was slightly different from those of recent modern humans. "It is very surprising to have a Homo sapiens fossil from a Châtelperronian context," Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London.

The researchers suggested that this hip bone belonged to an early modern human lineage that differed slightly from present-day modern humans. "We have found a new anatomically modern human lineage," study senior author Bruno Maureille, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux in France and head of research at France's National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), told Live Science.

Who Invented Certain Kinds of Tools? Humans or Neanderthals

In May 2020, in papers published in Nature and in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists announced the discovery of human bones and tools — dated to between 44,000 and 46,000 years ago — in Bulgaria’s Bacho Kiro cave, along, pendants made from cave bear teeth.Tom Metcalfe wrote for NBC News: “The finds also resolve a debate about distinctive tools and personal ornaments known as Bachokirian, after the cave. These show new ways of using stone, bone and antler that became common among Homo sapiens many thousands of years later. “Similar items made by Neanderthals have been found elsewhere. But the new finds indicate those Neanderthals adopted the new ways of making them from early Homo sapiens. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, NBC News, May 12, 2020]

“While Neanderthals were probably smarter than popular accounts suggest, it now seems they didn’t invent Bachokirian tools and ornaments on their own, said paleoanthropologist Richard Klein from Stanford University in California, who was not involved in the new research. Instead, it’s likely they adopted this new style of tools and ornaments from early Homo sapiens, “presumably by imitation or observation.” But the interactions between Neanderthal and early groups of humans in Europe remain unclear — although some Neanderthal genes are found in modern humans, indicating some interbreeding took place, he said. So why did the Neanderthals die out, if they were capable of copying the technologies of the new arrivals? “That's the ultimate question,” Klein said.

Proteins Help Determine That Châtelperronian Technology Was Invented by Neanderthals

Nikhil Swaminathan wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Archaeologists agree that hand axes and scrapers were definitely part of the Neanderthal toolkit, and modern humans are credited with developing points made of bone and antler, as well as flint blades. But in between these two types of technology, chronologically, are the so-called Châtelperronian tools, characterized by sawtooth edges and knives with convex backs. Researchers are still unsure which hominin was responsible for them. [Source: Nikhil Swaminathan, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, applied a relatively new technique — probing ancient bones for the remains of proteins — to solve the riddle at the Grotte du Renne, a cave located 150 miles southeast of Paris. Châtelperronian tools were discovered there, mostly in the 1950s, in association with ornaments such as bead necklaces and pendants, as well as hominin remains. The jewelry implies the deposit was made by modern humans, but the bones appear to be those of Neanderthals.

“Proteins are more robust than DNA, so they persist longer in bone, especially in warmer climates. The human and Neanderthal genomes — and, in turn, proteins — are nearly the same, so the team was on the hunt for small differences. “If you have a choice between DNA and proteins — with DNA around, you would want DNA,” says Matthew Collins, a professor of proteomics at the University of York and a collaborator in the new work. “If you want to push things further back in time, then no one’s really been looking at proteins.”

“The research team analyzed 28 bone fragments found close to the Châtelperronian tools and screened them for preserved proteins. They recovered about 70. After eliminating several as stemming from possible contamination during handling, they analyzed the remainder. “There were a number that are only active in bone during the first one or two years of life,” says Frido Welker, a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute, who helped lead the research. Based on the presence of those proteins, Welker explains, and the size of the bones, the scientists concluded the remains were from the skull of a breast-feeding infant.

“To figure out if it was a Neanderthal or human baby, they isolated sequences of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, and compared them to sequences found in modern humans. They specifically looked for snippets that are either found in low frequencies in humans or show slight differences from typical human versions. If any of these were present, the bones were likely Neanderthal. They hit on one that tends only to be found in human populations in Oceania — where modern humans carry more genetic material conserved from earlier hominin populations.

“As another data point, analysis of mitochondrial DNA later confirmed what the protein analysis suggested: The infant was Neanderthal. Radiocarbon dating of a section of skull put its age at roughly 42,000 years old. Thomas Higham, who runs a radiocarbon lab at the University of Oxford, and who had previously concluded that the finds at Grotte du Renne were jumbled together from two different time periods, called the new study “hugely exciting.” “It looks as though the Châtelperronian is a Neanderthal industry,” he says. “I think it is quite possible that Neanderthals were capable of making and using personal ornaments.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024