Home | Category: God, Satan, Heaven and Hell

HELL

Hortus Deliciarum Hell as a place of punishment and suffering where sinners are condemned is a concept that exists in Christianity, Islam and Hinduism and to a lesser extent in Judaism, Buddhism and many tribal religions in the world. What hell is or like is widely disputed even within Christianity.

The concepts of hell as a place of punishment for evildoers was adapted by Zoroastrianism and passed on to Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Early concepts of Christian hell were based on Greek Hades and Jewish of Sheol. In a 2014 Pew survey, six out of ten Americans said they believed in an afterlife in which people are punished for evil deeds, According to a 2000 U.S. News and World Report poll, 34 percent of Americans said they believed that hell is a real place where people suffer fiery torment; 53 percent said they believed it was an anguished state of existence eternally separated from God; 11 percent said they didn’t know.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Chronologically speaking, hell didn’t always feature in conceptual maps of the afterlife. In the Hebrew Bible there are frequent references to Sheol, a place of shadows located physically beneath us. This is where everyone goes when they die, because people are buried in the ground. Upon occasion, Sheol opens its jaws and swallows people — a phenomenon we probably know as earthquakes, but which can in part explain why death is described as swallowing people up. Without a doubt, Sheol is a generally dismal place where people are separated from God, but it isn’t reserved for the especially wicked. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, March 22, 2015

In Judaism, the idea of post-mortem judgment, reward, and punishment seems to have gathered strength in the second century BCE. During this period Israel was again a conquered land, ruled by a succession of oppressive Greek empires. Along with high taxation and cultural colonialism, Alexander the Great and his successors brought the ideas of post-mortem punishment in the underworld to the Holy Land. There were many other potential religious groups envisioning post-mortem destruction, but the Greeks appear to have been the most influential. Think Sisyphus pushing a boulder up a hill, Tantalus being cursed with eternal thirst, and Prometheus having his liver eaten on a daily basis. For beleaguered and oppressed Jews, the idea that the injustices levied on them in the present would be rectified in the afterlife held a lot of appeal. And that kind of justice involved punishing their tormentors as well as rewarding the righteous.

Punishing the wicked required some real estate. So pits of torment, restraint, and interim punishment start to appear in ancient otherworldly topographies. Usually hell is a region beneath the earth, but it is sometimes a remote and far-flung place at the ends of the earth. . . . . A whole host of names and regions—Gehenna, Hades, the Lake of Fire, and the Valley of Fire—are used to describe these places of pain and confinement.

Websites and Resources on Christianity BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Answers christiananswers.net ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; Internet Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christian Denominations: Holy See w2.vatican.va ; Catholic Online catholic.org ; Catholic Encyclopedia newadvent.org ; World Council of Churches, main world body for mainline Protestant churches oikoumene.org ; Online Orthodox Catechism published by the Russian Orthodox Church orthodoxeurope.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Penguin Book of Hell” (illustrated) and edited by Scott Bruce (2018) Amazon.com ;

“The History of Hell” by Alice Turner(1993) Amazon.com ;

“Hell: A Guide” by Anthony DeStefano, Zach Hoffman, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife” by Bart D. Ehrman Amazon.com ;

“Heaven: A History” by Colleen McDaniel and Bernard Lang Amazon.com ;

“Heaven: A Comprehensive Guide to Everything the Bible Says About Our Eternal Home” by Randy Alcorn Amazon.com ;

“Death, Judgment, Heaven, Hell: Meditations on the Four Last Things

by St. Alphonsus Liguori, Darrell Wright Ph.L., et al. Amazon.com ;

“Purgatory: Explained by the Lives and Legends of the Saints” by Rev. Fr. F. X. Shouppe S.J. Amazon.com ;

“Purgatory: The Two Catholic Views of Purgatory Based on Catholic Teaching and Revelations of Saintly Souls” by Fr. Frederick William Faber Amazon.com

“The Origin of Satan” by Elaine Pagels Amazon.com ;

“The Satan: How God's Executioner Became the Enemy” by Ryan E. Stokes and John J. Collins Amazon.com ;

“Satan: His Personality, Power, and Overthrow” by E.M. Bounds Amazon.com ;

“The Second Coming of Christ” (Illustrated) by Clarence Larkin Amazon.com ;

“Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation” by Elaine Pagels Amazon.com ;

“The Book of Revelation Made Clear: A Down-to-Earth Guide to Understanding the Most Mysterious Book of the Bible” by Tim LaHaye and Timothy Parker Amazon.com ;

“On the Resurrection of the Dead and on the Last Judgement” by Johann Gerhard Amazon.com ;

Hell in the Old Testament

Early Jews developed the concept of Sheol, an Underworld where the all dead resided in a kind of semi-existence. Genesis, 1 Kings, Psalms and Job all mention Sheol. Eccles 9:10 describes it as a place in which "you are bound, there is neither dying nor thinking neither understanding nor wisdom." When Jacob concluded his beloved son was dead, he moaned, “I shall go down to Sheol to my son, mourning.”

The concept of Sheol was partly based on the Greco-Roman belief of Hades, a dreary and depressing place where people went after they died. The Pharisees, a Jewish sect that lived around the time of Jesus, embraced the Greco-Roman idea of heaven as place with distinct “levels,” or areas. In the 2nd century B.C. when the Hebrew scriptures were translated to Greek, the word Hades was used instead of Sheol.

Isaiah predicts a punishment of fire for the wicked and Daniel describes “shame and everlasting contempt” for evildoers. There is no mention of Hell in the Old Testament as a permanent place of punishment for the wicked but Hades is represented as a temporary abode for the wicked. The Book of Enoch reads: “And this has been made for sinners when they die and are buried in the earth and judgment has not been executed upon them in their lifetime. Here their spirts shall be set apart in great pain, till the great day of judgment, scourging, and torments of the accursed for ever.”

Judaism widely reject a literal interpretation of hell. In the 18th century the influential Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn reasoned that hell couldn’t exist because a punishment of eternal suffering was is incompatible with God’s mercy.

Zoroastrian Beliefs on Heaven and Hell

The concept of heaven and hell was adapted by pre-Christian Zoroastrianism and passed on to Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Zoroastrians believe that individuals are responsible for their own souls and their fate in the afterlife is determined by the good and evil deeds they perform while they are alive. After a person dies the soul remains bound to the earth for three days. On the forth day the soul rise with the sun to the Chinvat Bridge, the Zoroastrian equivalent of a Judgement Day.

For people who have performed mostly bad deeds the bridge narrows to a razor’s edge and they fall into the House of Lies, a place ruled by Ahriman. The Zoroastrian concept of hell was adapted in part from views about places of afterlife punishment for sinners that had been around for a long time in religions in Egypt, Persia, India and other places.

People who have performed mostly good deeds cross the bridge, escorted by an attractive member of the opposite ex, to one of the seven garden-like, heaven-like paradises near the sun. The Persian word “pairi-daeza”, or enclose, is the source of the word paradise. Zoroastrians regard judgement, heaven and hell as metaphorical places that can bring great bliss or pain but are largely incomprehensible to the living.

In addition to heaven (Behesht) and hell (Dozakh) Zoroastrians have a place in the middle (Hamestegan), a realm with no joy but only mild suffering. Here they wait in a kind of twilight until resurrection at the end of time. It was not like purgatory in that one could not work one’s way to heaven.

Zoroastrians also have an end of the world scenario ushered in by arrival of a final Messiah. When this occurs all souls are resurrected and the mountains turn to river of molten metal. During a final judgment everyone is immersed in the molten rivers. For the pure it feels like a warm bath. For wicked they endure horrific suffering as their skin and flesh melts off their bones. In early Zoroastrian text the souls of the wicked were destroyed forever. In later texts, the wicked were thus purified and allowed to dwell in paradise.

See Separate Article: ZOROASTRIANISM factsanddetails.com

Chronology of Hell

Hell 400 B.C. —The Ancient Greek underworld — guarded by Cerberus — was always grim, but the idea of eternal torture for earthly wrongdoing didn't begin to appear until the age of Socrates. [Source: Juan Bernabeu, Smithsonian magazine, October 2018]

A.D. 200-300 — A burning river of fire and other flaming torments described in the Apocalypse of Paul shaped medieval Europe’s understanding of damnation — and our own.

594 —Purgatory didn’t become church doctrine until 1245, but the concept emerged in the sixth century in works like Pope Gregory I’s Dialogues.

1000-1300 — For centuries, the idea of hell was confined to cloisters. At the turn of the millennium, clergy began to spread vivid tales to laypeople to encourage good behavior.

1150 — Penned by an Irish monk, the Visio Tnugdali was the most graphic map of the devil’s lair until Dante; it inspired the 16th-century paintings of Hieronymus Bosch.

1320 — Dante’s Inferno brought organization to the afterlife, with clear geography and punishment to match the sin. The worst fate was the frozen ninth circle.

1665 — Post-Reformation Protestants embraced hell, but they focused more on God's judgment than physical pain, as in this Puritan tale of the “resurrection of damnation.”

1874 — Even as the rise of science diminished the fear of the underworld, a pamphlet for kids at a Christian camp in England threatened eternal, “aching darkness.”

Hell in the New Testament

There was not many descriptions of hell in the New Testament. Mark warns of “the fire that never be quenched” and “the undying worm” waiting sinners who “offend.”In Luke, Dives was taken to Hades, “where he was in torment,” but inexplicably he can talk to Lazarus who was sent presumably to heaven. The Gospel of Matthew mentions perdition, the “outer darkness,” a furnace of fire, the damnation of Hell and an everlasting punishment. There are also some indications that hell doesn’t exist. Paul said that “the wage of sin is death,” not damnation in an afterlife.

Many early Christians believed that everyone would have to pass through fire as a kind of test. Paul wrote in I Corinthians 3:13; “For that day dawns in fire, and the fire will test the worth of each man’s work.” This day was supposed to occur when Jesus returned

Jesus seemed to indicate the wicked would go hell immediately after death. According to the Gospels of Nicodemus and Bartholomew, which never became part of the Christian canon, Jesus’s descends into Hell after his crucifixion and before his resurrection.

Revelation describes Hell as lake of fire and an eternal place of punishment where the damned were sent after Judgement at the end of the world. According to Apocalypse of Peter, Hell is a place where sinners are thrown in an unquenchable fire, where the tongues of blasphemers are hung up, where fornicators are dumped in a pit, where murders face venomous beasts, clouds of worms and torment from the souls of the people they murdered and where women who had abortions have their eyes pierced by their unborn children.

Jesus and Hell

Bart D. Ehrman, a University of North Carolina professor, a leading New Testament scholar, and an evangelical-turned-agnostic, wrote in Time: ““Most people today would be surprised to learn that Jesus did not believe in hell as a place of eternal torment. In traditional English versions, he does occasionally seem to speak of “Hell” — for example, in his warnings in the Sermon on the Mount: anyone who calls another a fool, or who allows their right eye or hand to sin, will be cast into “hell” (Matthew 5:22, 29-30). But these passages are not actually referring to “hell.” The word Jesus uses is “Gehenna.” The term does not refer to a place of eternal torment but to a notorious valley just outside the walls of Jerusalem, believed by many Jews at the time to be the most unholy, god-forsaken place on earth. It was where, according to the Old Testament, ancient Israelites practiced child sacrifice to foreign gods. The God of Israel had condemned and forsaken the place. [Source: Bart D. Ehrman,, Time, May 9, 2020]

“In the ancient world (whether Greek, Roman, or Jewish), the worst punishment a person could experience after death was to be denied a decent burial. Jesus developed this view into a repugnant scenario: corpses of those excluded from the kingdom would be unceremoniously tossed into the most desecrated dumping ground on the planet. Jesus did not say souls would be tortured there. They simply would no longer exist. Jesus’ stress on the absolute annihilation of sinners appears throughout his teachings. At one point he says there are two gates that people pass through (Matthew 7:13-14). One is narrow and requires a difficult path, but leads to “life.” Few go that way. The other is broad and easy, and therefore commonly taken. But it leads to “destruction.” It is an important word. The wrong path does not lead to torture.

“So too Jesus says the future kingdom is like a fisherman who hauls in a large net (Matthew 13:47-50). After sorting through the fish, he keeps the good ones and throws the others out. He doesn’t torture them. They just die. Or the kingdom is like a person who gathers up the plants that have grown in his field (Matthew 13:36-43). He keeps the good grain, but tosses the weeds into a fiery furnace. These don’t burn forever. They are consumed by fire and then are no more.

“Still other passages may seem to suggest that Jesus believe in hell. Most notably Jesus speaks of all nations coming for the last judgment (Matthew 25:31-46). Some are said to be sheep, and the others goats. The (good) sheep are those who have helped those in need — the hungry, the sick, the poor, the foreigner. These are welcomed into the “kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.” The (wicked) goats, however, have refused to help those in need, and so are sent to “eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.” At first blush, that certainly sounds like the hell of popular imagination.

“But when Jesus summarizes his point, he explains that the contrasting fates are “eternal life” and “eternal punishment.” They are not “eternal pleasure” and “eternal pain.” The opposite of life is death, not torture. So the punishment is annihilation. But why does it involve “eternal fire”? Because the fire never goes out. The flames, not the torments, go on forever. And why is the punishment called “eternal”? Because it will never end. These people will be annihilated forever. That is not pleasant to think about, but it will not hurt once it’s finished.

“And so, Jesus stood in a very long line of serious thinkers who have refused to believe that a good God would torture his creatures for eternity. The idea of eternal hell was very much a late comer on the Christian scene, developed decades after Jesus’ death and honed to a fine pitch in the preaching of fire and brimstone that later followers sometimes attributed to Jesus himself. But the torments of hell were not preached by either Jesus or his original Jewish followers; they emerged among later gentile converts who did not hold to the Jewish notion of a future resurrection of the dead. These later Christians came out of Greek culture and its belief that souls were immortal and would survive death.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “What Jesus Really Said About Heaven and Hell” time.com/

Doomed souls in an imagining of the Greek underworld

Greek Views of Death and Hell

Bart D. Ehrman, wrote in Time: “From at least the time of Socrates, many Greek thinkers had subscribed to the idea of the immortality of the soul. Even though the human body dies, the human soul both will not and cannot. Later Christians who came out of gentile circles adopted this view for themselves, and reasoned that if souls are built to last forever, their ultimate fates will do so as well. It will be either eternal bliss or eternal torment. [Source: Bart D. Ehrman,, Time, May 9, 2020]

“This innovation represents an unhappy amalgamation of Jesus’ Jewish views and those found in parts of the Greek philosophical tradition. It was a strange hybrid, a view held neither by the original Christians nor by ancient Greek intelligentsia before them. Still, in one interesting and comforting way, Jesus’ own views of either eternal reward or complete annihilation do resemble Greek notions propagated over four centuries earlier. Socrates himself expressed the idea most memorably when on trial before an Athenian jury on capital charges. His “Apology” (that is, “Legal Defense”) can still be read today, recorded by his most famous pupil, Plato. Socrates openly declares that he sees no reason to fear the death sentence. On the contrary, he is rather energized by the idea of passing on from this life.

“For Socrates, death will be one of two things. On one hand, it may entail the longest, most untroubled, deep sleep that could be imagined. And who doesn’t enjoy a good sleep? On the other hand, it may involve a conscious existence. That too would be good, even better. It would mean carrying on with life and all its pleasures but none of its pain. For Socrates, the classical world’s most famous pursuer of truth, it would mean endless conversations about deep subjects with well-known thinkers of his past. And so the afterlife presents no bad choices, only good ones. Death was not a source of terror or even dread.

“Twenty-four centuries later, with all our advances in understanding our world and human life within it, surely we can think that that both Jesus and Socrates had a lot of things right. Jesus taught that in this short life we have, we should devote ourselves to the welfare of others, the poor, the needy, the sick, the oppressed, the outcast, the alien. We should listen to him.

“But Socrates was almost certainly right as well. None of us, of course, knows what will happen when we pass from this world of transience. But his two options are still the most viable. On one hand, we may lose our consciousness with no longer a worry in this world. Jesus saw this as permanent annihilation; Socrates as a pleasant deep sleep. In either scenario, there will be no more pain. On the other hand, there may be more yet to come, a happier place, a good place. And so, in this, the greatest teacher of the Greeks and the founder of Christianity agreed to this extent: when, in the end, we pass from this earthly realm, we may indeed have something to hope for, but we have absolutely nothing to fear.

Tartarus — Greek Hell

Tartarus in the Underworld was a hell-like place but only certain gods, not mortals, were sent there. Greece was so filled with wicked people that philosophers wondered whether the Underworld was large enough to accommodate all the ones who died since the beginning of time. This gave rise to the belief that maybe Tartarus was is in the southern hemisphere not underground, which in turn discouraged explorers from heading south. The Roman historian Pliny pointed out that it was also strange that even though the route to Hades was well-mapped no miners ever came across it. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

Tartarus: was a prison area below the ‘House of Hades', presided over by Kronos (Zeus' father and predecessor) who is as much a prisoner there as anyone else (In some myths, Kronos is released and returned to Olympos, like Prometheus). The place is guarded by the Hundred-Handed Giants. Humans who are guilty of special crimes against the gods and their code are sent here for eternal punishment. [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class ++]

Plato wrote in “Republic” X, 615-617: “‘For indeed this was one of the dreadful sights we beheld; when we were near the mouth and about to issue forth and all our other sufferings were ended, we suddenly caught sight of him and of others, the most of them, I may say, tyrants. But there were some of private station, of those who had committed great crimes. And when these supposed that at last they were about to go up and out, the mouth would not receive them, but it bellowed when anyone of the incurably wicked or of those who had not completed their punishment tried to come up. And thereupon,’ he said, ‘savage men of fiery aspect who stood by and took note of the voice laid hold on them and bore them away. But Ardiaeus and others they bound hand and foot and head and flung down and flayed them and dragged them by the wayside, carding them on thorns and signifying to those who from time to time passed by for what cause they were borne away, and that they were to be hurled into Tartarus. [Source: Plato. Republic, “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vols. 5 & 6 translated by Paul Shorey. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1969]

See Separate Articles: ANCIENT GREEK IDEAS ABOUT DEATH, THE AFTERLIFE, HADES AND THE SOUL africame.factsanddetails.com ; JEWISH IDEAS ABOUT DEATH, AFTERLIFE AND THE SOUL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

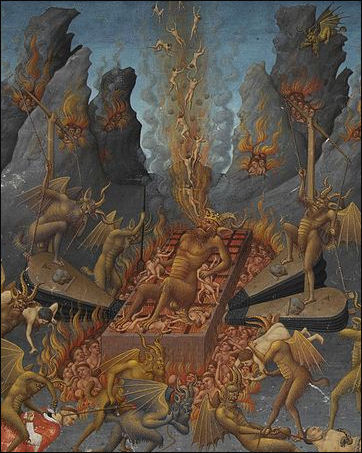

Hell by Luca Signorelli

Hell in the Early Christian Era

For early Christians hell was not a metaphor but a real place with rivers, islands, prisons and torture chambers. In early Christian teaching after the final judgment, the are condemned to a hell of fire called “gehenna” , a Greek word derived from the Hebrew “Gehinnom” and referring to the desolate Valley of Hinom, just south of the Old City in Jerusalem, where the ancient Canaanites reportedly conducted human sacrifices in which children were immolated in front of their parents and the ancient Jews dumped their trash and burned it and dishonored corpses were disposed of. Describing the Valley of Hinnom in 1999, Edwin Black wrote in the Washington Post, “Everywhere you see scorches and smolder from trash fires. Rivulets of urine trickle down from open sewers at the cliffs above, watering thorn bushes, weeds...You smell the stench of decaying offal, the congeal stink of putrefied garbage...Worms and maggots slither throughout.”

There was a lot of speculation and debate about Hell in the early years of Christian. Theologians tried to resolve inconsistencies in the scriptures and decide whether it was a concrete place or a state of suffering or separation from God. Sometimes these theologians wrote in their own name, sometimes they attributed their thoughts to Apostles. Theologians wrestled with thorny issues like, “Were the wicked to suffer forever?” and “If so was this a failure of Gods effort to redeem mankind” (some concluded that damnation was only temporary and even Satan would one day be saved).

There was also a sense that Hell will bring harsh justice to people who gave Christians a hard time. A North African theologian who wrote in the A.D. 2nd century during the persecution of Christians in Rome wrote: “What a panorama....Mighty kings whose ascent to heaven used to be announced publically groaning now in the depths with Jupiter himself...Governors who persecuted the name of the Lord melting into flames fiercer than those they kindled for brave Christians...The famous charioteer will toast in his fiery wheel; the athletes will cartwheel not in the gymnasium but in the flames.”

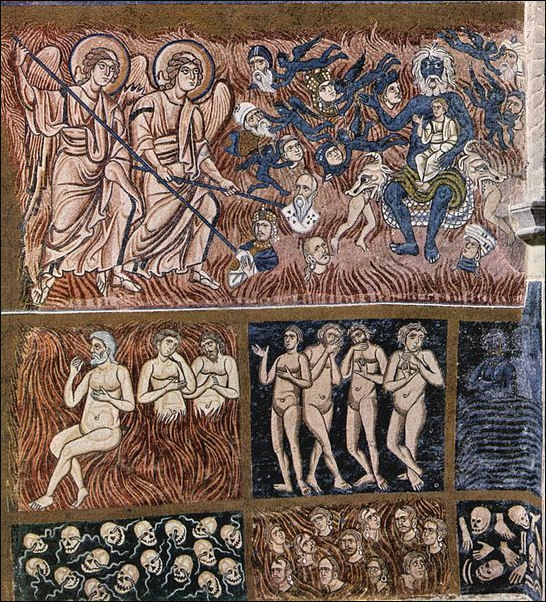

Hell in the Middle Ages

In the A.D. 5th century, Augustine upheld the idea of an eternal Hell “of material fire and torment to the bodies of the damned.”, to which atheists and the truly wicked were condemned, but argued that those who committed lesser sins such as overeating and laughing too much would be saved by means of passing through a “purgatorial fire before the Judgement Day.

In the Middle Ages, the idea of purgatory was developed, Satan became a major figure, reports of encounters with demons increased, heretics and witches were burned, and vivid descriptions of hell were presented in the written form and in art.

The nun Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1099-1179) described hell as "deep and braid, full of boiling pitch and sulphur, and around it were wasps and scorpions, who created but did not injure the souls of therin; which were the souls of those who had slain in order not to be slain...Near a pond of clear water I saw a great fire. In this some souls were burned and others were girdled with snakes, and others drew in and again exhaled the firelike breath, while malignant spirits cast lighted stones at them...And I saw a great swamp, over which hung a black cloud of smoke, which was issuing from it, And in the swamp there swarmed a mass of little worms. ere were the souls of those who in the world delighted in foolish merriment."

Hell and Purgatory by Meister von Torcello

Hell in the Renaissance

Dante gave a vivid vision of Hell as an inferno. His Hell was divided into seven layers, each associated wi the a deadly sin, with the worst being at the bottom. So convinced that Dante’s Hell was a real, Galileo used his description to calculate that Hell was 405 11/22 miles below the surface of the earth.

Milton also gave us elaborate visions of Hell with burning sulfur, dudgeons, fiery downpours and hideous demons and helped define Hell in the English-speaking world. Paintings by Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) provided lurid images of the kind of beasts and landscapes one oculd expct to find there.

The great philosophers of the Enlightenment — Locke, Descartes and Hobbes — tackled the issue of Hell. Locke wrote that sinners in Hell “shall not live forever. This is so plain in Scripture, and is so everywhere inculcated — that the wages of sin is death, and the reward for righteousness is everlasting life...that one would wonder how the readers could be mistaken.” Others made a case for universal salvation. Later on people like Voltaire mocked the idea of Hell altogether.

During the Reformation and Counter-Reformation concepts of hell became increasingly abstract. Hell was viewed a real place but not one necessarily filled with fire. Rather it was seen a place of deep despair associated with separation from God.

Hell in the Modern Times

In the mid 1700s, the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg offered descriptions of hell that were just as material and accessible as the ones he offered of heaven. In the 1800s, Hell became less of something that people took literally and more of a symbol and a literary device used by people such as Lord Byron, William Blake and Baudelaire.

In the 20th century, fundamentalists and evangelicals pushed forward the fire and brimstone vision of hell while most people had difficult taking that view seriously. In films, art and the media, the images of hell and the devil were more often than not ridiculed and used as comic device.

In 1999, the an editorial in the influential Jesuit magazine “La Civilta Catolica” declared Hell “is not a “place” but a “state,” a person’s “state of being,” in which a person suffers from the deprivation of God.” A few days later Pope John Paul II added, “rather than a place, hell indicates the state of those who freely and definitely separate themselves from God” and said that Bible “uses a symbolic language.”

Views of Hell by Different Christian Denominations

In Catholicism hell is the "state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed" which occurs by the refusal to repent of mortal sin before one's death, since mortal sin deprives one of sanctifying grace. In the A.D. 5th century, Augustine upheld the idea of an eternal Hell, to which atheists and the truly wicked were condemned, but argued that those who committed lesser sins such as overeating and laughing too much would be saved by means of passing through a “purgatorial fire” before the Judgement Day.

In 1999, the an editorial in the influential Jesuit magazine La Civilta Catolica declared Hell “is not a ‘place’ but a ‘state,’ a person’s ‘state of being,’ in which a person suffers from the deprivation of God.” A few days later Pope John Paul II added, “rather than a place, hell indicates the state of those who freely and definitely separate themselves from God” and said that Bible “uses a symbolic language.”

On Orthodox Christian views of Hell, one person posted on Redditcom in 2018; From what I have read, the Orthodox view (or one view, perhaps) is that Hell is not eternal punishment in the sense of eternal burning in Hell, but eternal separation of God. Another posted: St. Gregory Palamas teaches that as the death of the body is separation of the soul from the body, the death of the soul is the separation of the soul from God. This is why eternal damnation is referred to as the “second death” (Cf. Book of Revelation). Of course, this separation is not complete, as God is everywhere. But, it is a kind of existential separation. As an analogy, if you had a falling-out with a friend, you feel separated from them even if they are sitting right next to you. In fact, the close proximity makes this feeling of separation even more acute. [Source: Reddit.com]

In historic Protestant traditions, hell is the place created by God for the punishment of the devil and fallen angels (cf. Matthew 25:41), and those whose names are not written in the book of life (cf. Revelation 20:15). It is the final destiny of every person who does not receive salvation, where they will be punished for their sins. People will be consigned to hell after the last judgment. The nuances in the views of "hell" held by different Protestant denominations are largely a function of the varying Protestant views on the intermediate state between death and resurrection; and different views on the immortality of the soul or the alternative, the conditional immortality. For example, John Calvin, who believed in conscious existence after death, had a very different concept of hell (Hades and Gehenna) to Martin Luther who held that death was sleep. [Source: Wikipedia

Purgatory and Limbo

Catholics believe in Heaven and Hell, but also in Purgatory, a place for those who have died in a 'state of grace' (that is, they have committed 'venial' or forgivable sins) and may not go straight to Heaven. The concept developed so that majority of people could reach heaven. In the A.D. 5th century, Augustine upheld the idea of an eternal Hell “of material fire and torment to the bodies of the damned.", to which atheists and the truly wicked were condemned, but argued that those who committed lesser sins such as overeating and laughing too much would be saved by means of passing through a “purgatorial fire before the Judgement Day. In the Middle Ages, the idea of purgatory was developed, Satan became a major figure, reports of encounters with demons increased, heretics and witches were burned, and vivid descriptions of hell were presented in the written form and in art.

Muhammad faces Hell Catholics believe that the soul is immortal. At death each man and woman is sent to Heaven or Hell based on their deeds during their life and obedience to the laws of God and the church. Before entering Heaven many souls must spend time in Purgatory to become pure. The concept of purgatory arose in part because of the confusion over what happened to people after they died and waited for the second coming of Christ, when they would be whisked off to heaven.

'Limbo' is a way of dealing with the death of unbaptized babies. According to the BBC: “One of the biggest problems the Catholic Church faced over the years was the problem of children who died before they were baptised. Before the 13th Century, all unbaptised people, including new born babies who died, would go to Hell, according to the Catholic Church. This was because original sin had not been cleansed by baptism. This idea however was criticised by Peter Abelard, a French scholastic philosophiser, who said that babies who had no personal sin didn't even deserve punishment. [Source: September 17, 2009 BBC |::|]

Muslim Hell

For Muslims, Hell, known as Jahannam, waits for those who do not submit to Allah. According to the traditional Islamic belief, hell lies in a crater over which there is a narrow bridge. All souls must cross the bridge (See Judgement Above). Although Allah is frequently revered to as “The Compassionate and Merciful” the Qur’an is full of reference to the eternity of hell with no chances of escape or redemption for sinners. In the Qur’an hell is described in graphic terms as a place full with a “lake of fire,” a “burning bed of misery” with serpents and tortures and only “boiling, fetid water.” There are seven gates or layers of Hell, each reserved for a different kind of infidel or wicked person, guarded by angels not devils. At the bottom there is a horrible tree called “Zaqqim” , whose fruit consists of the heads of devils. Sinners are forced to eat the fruit which burns their throats and digestive system like molten metal.

Many images of hell don’t come from the Qur’an but rather from religious texts written later. In the 11th century Book of Resurrection, for example, an angel of hell is said have “as many hands and feet as there people in the fire. With each foot and hand he makes [people] stand and sit and puts them in shackles and chains When he looks at the Fire, the Fire consumes itself in fear of the angel.”

Hell, some Muslims believe, is shaped like a funnel with a “purgatorial fire” with Muslims who committed egregious sins in uppermost of the seven layers, followed by a “flaming fire” for Christians, a “raging fire” for Jews, a “blazing fire” for the Sabeans of southern Yemen, the “scorching fire” for the Zoroastrians, the “very fierce fire” for the polytheists. The bottom layer is an abyss for the hypocrites of Islam.

See Separate Article: ISLAMIC VIEWS ON HEAVEN, HELL, DEATH AND JUDGEMENT factsanddetails.com

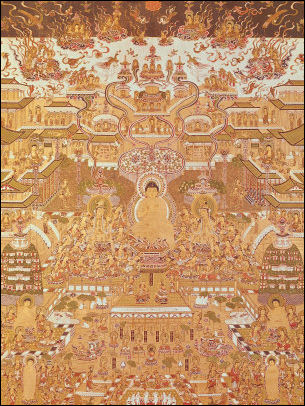

Buddhist Hell

Buddhist Hell

from Dunhuang Caves in China In accordance with the Wheel of Life model, hell is one of six possible destinations after rebirth and, like heaven, it is a stop on the way to enlightenment. The residents of hell can escape if they move towards enlightenment. Hell itself is composed multiple hells (usually eight), located below the earth. Each hell is lower than the previous one and and is regarded as a worse place to be than the one before it. In addition to hell there are realms of hungry ghosts and beasts (See Wheel of Life), which are not pleasant places to be but are not as bad as the eight hells.

Hell is viewed as a place for sinners and evildoers and the hell one ends up in fits their sins. Buddhists believe it is possible to be banished to hell for thousands even millions of years, based on their karma, before being released. They also believe it is possible to be reborn into hell again if one doesn’t get his or her act together. Some Buddhists see these hells as real places. Others view them as symbolic.

According to one view the eight hells are (from least worst to worst): 1) The Hell of Constantly Reviving, where people who took the lives of creatures are killed in the same way they killed; 2) the Black Lines Hell, where thieves are soaked in Black ink and cut into pieces with burning saws; 3) the Squeezing Hell, where people accused of sexual misbehavior are repeatedly squeezed, burned up, crushed and cut into pieces; 4) the Screaming Hell, where people who misused drugs and intoxicants have boiling liquids poured down their throats.

See Separate Articles: BUDDHIST HEAVEN, HELL AND AFTERLIFE BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

Text Sources: Internet Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024