Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

ANCIENT GREEK TRANSPORTATION

Leather sandal soles The waters around Greece were relatively placid, facilitating sea travel, and harbors were plentiful while land transport presented challenges. There were overland roads but most were basic and unsuitable for the transportation of large cargoes and in many cases even wheeled vehicles. The main reason for a lack of good roads was Greece’s geography. There were mountain ranges all over the place. The political divisions of the Greek city-states were also was an obstacle. Few individual city-states could assemble the work force or financial resources to build and maintain a reliable network of highways, plus they didn’t want to make it too easy for their enemies to attack them, [Source Encyclopedia.com]

In historic times it appears that people travelled very little in carriages. Of course these had to be used on long journeys, especially when women were travelling; then they used four-wheeled carriages, which were sometimes used for sleeping in; and they also had smaller two-wheeled carts. But as a rule men travelled on horse-back or mule-back, and very often merely on foot, followed by one or many slaves, who carried the baggage required for the journey, in particular bed-coverings, clothes, utensils, etc. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

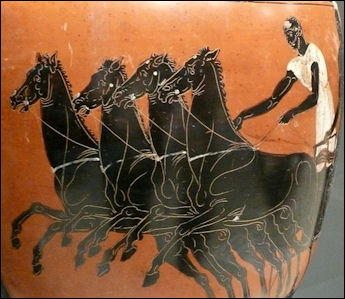

The Mycenaeans built roads graded for wagons and chariots. However ships were the primary vehicle for moving goods. Much fewer goods could be carried overland and the going was more difficult. Egyptians, Assyrians and Greeks had chariots. The ancient Greeks seem to have used chariots mainly as transport and racing vehicles. One of the reasons for this was the rugged Greek countryside did not provide enough grazing land to feed a lot of horses, nor did it lend itself to chariot battles which need a lot of flat open space.

The Greeks never attained as great perfection in road-making as the Romans; apparently those roads were kept in best condition which led to the national sanctuaries, and here regular tracks were cut out of the rocky ground, and there were places for passing other carriages, halting places, etc. This was not, however, the case with all the roads, and we must not assume that ancient Greece possessed a well-kept complicated network of streets

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT GREEK INFRASTRUCTURE: TUNNELS, ROADS, THE DIOLKOS, LIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK MERCHANT SHIPS: TYPES, CARGOES, SHIPWRECKS europe.factsanddetails.com

SEA TRAVEL AND NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT GREEK NAVY: FIGHTING TRIREMS, OARSMEN AND SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“Trade, Transport and Society in the Ancient World: A Sourcebook” ”” (Routledge Revivals) by Onno Van Nijf and Fik Meijer (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Other Greeks: The Family Farm and the Agrarian Roots of Western Civilization”

by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference” (Cairo 2012)

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“The Greeks Overseas: The Early Colonies and Trade” by John Boardman (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Over Land and Sea: the Long-Distance Trade, Distribution and Consumption of Ancient Greek Pottery” by Alejandro Garés-Molero, Diana Rodríguez-Pérez (2025) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Athens: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life In Ancient Greece, People & Places” by Nigel Rodgers (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Traveling in Ancient Greece

5th century BC figurine Traveling played a far less important part in the life of the Greeks than it does at the present day. In ancient times almost the only inducement for travelling was business. The merchant plied his trade chiefly as a sailor, the small shopkeeper travelled about the country as a pedlar. In the heroic period we also find artisans and travelling singers on their wanderings, and in the first centuries of the development of art, and to some extent even afterwards, sculptors and architects were summoned from a distance to execute commissions under the orders of the State, or some special board of officials. But those who were neither merchants nor artisans had less inducement to travel; for military expeditions, which of course were numerous, can hardly be included among journeys. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

There were also official embassies and pilgrimages to celebrated shrines, or visits to the great national festivals. Again, Solon, Herodotus, and others travelled for political or scientific purposes, with a view to study history or ethnography, that they might learn to know foreign nations, their manners and customs, countries and buildings. In the Alexandrine period, journeys were also undertaken for purposes of natural science. Our modern custom of visiting foreign lands for the sake of their natural beauty was unknown in Greek antiquity, but we must not on that account suppose that the ancients had no feeling for natural beauty. The Odyssey gives a picture of travel in heroic times; the common man trudges along on foot, while the rich man goes in his carriage, drawn by horses or mules, and the fact that the latter was possible even in the mountainous Peloponnesus, proves that even at that period good roads must have existed there.

If it was necessary to spend the night anywhere on a journey of several days, the widespread beautiful custom of hospitality which prevailed in ancient times, and made men regard every stranger as under the protection of Zeus, enabled them to find shelter; and, though this custom could not maintain itself in later times in its full extent, yet the effects of it still remained, and many people entered into a sort of treaty of hospitality with men in other towns, which was usually handed on to the descendants.

Still this custom of “guest-friendship” was not sufficient to supply shelter for all travellers; therefore inns were opened in large trading cities, near harbours, and places of pilgrimage, such as Delos, Delphi, Olympia, etc., where strangers were entertained for payment. These inns were of very various character — some of them apparently supplied only rooms and a little furniture, especially bedsteads, while the stranger brought his own bed and coverlets, and had to provide his own food; others supplied food and drink, and were often houses of ill-fame, and in consequence it is natural that the position of inn-keeper should have been generally looked down upon in Greek antiquity.

Probably these inns were not particularly pleasant places to stay in; very often the landlord cheated the travellers, and it was customary to arrange the price of everything beforehand; there were also inns which were used as hiding-places by robbers and thieves, and thus might prove dangerous quarters for the guests. Another disagreeable accompaniment of southern inns, even in the present day, is hinted at by Aristophanes in the “Frogs,” when Dionysus, on his journey to Hades, inquires for the inns in which there are fewest fleas. Travellers do not seem to have troubled themselves about passports; a legitimation was only necessary when the town to which they were going was engaged in war, or when they went into a hostile country in time of war. But to travel at all at such times was not advisable, for the roads, which at no time were specially safe, were then infested by travelling mercenaries or marauders. Sometimes travellers had to submit to an examination of their luggage. Officials generally farmed out the tolls to private undertakers, and these therefore had, or at any rate took, the right, if they suspected travellers of trying to smuggle dutiable articles, to stop them and examine their luggage, and sometimes even to open letters which they had by them.

Foot Travel in Ancient Greece

Because of the nature of Greek roads, the most common way to travel along them was on foot. According to Encyclopedia.com: It is clear from Pausanias’s descriptions that he did most of his traveling through Greece as a pedestrian, and other descriptions of travel confirm that this mode of locomotion was used far more frequently than any other. Many vase paintings depict the travelers’ god Hermes wearing special garments.

Travelers’ clothing consisted of sturdy footwear, a broad-brimmed hat to protect the person from the Mediterranean sun, and, for men, a shorter garment than they were accustomed to wearing around town, leaving more room for their legs to move. For particularly strenuous walks, men would hitch up their garments even further and travel “well-girt.” A traveler planning on an overnight stay carried with him a sack containing bedding in addition to food and extra clothing.

Pausanias measured his routes both in terms of distance and time, allowing his readers to calculate how quickly he walked. (It works out to a little less than three miles per hour, which, over difficult terrain, and figuring time for rest and for meals, is a fairly respectable pace.) There is some evidence that when goods needed to be transported overland they would sometimes be carried on foot by people using packs or shoulder braces. However, the average person could not haul more than fifty pounds over great distances, so no large-scale movements of goods were likely to have been undertaken in this manner.

Horse Riding in Ancient Greek

horse on the Elgin Marbles Riding was a usual mode of travel in ancient Greece, as it is still in many parts of that mountainous country; and, while carts and carriages of various kinds gradually came into service among the Romans, in Italy, too, the horse was the commonest means of travel. But although the Greeks and Romans were good horsemen, they were probably not the equals of the best modern riders, owing to the fact that they had no saddles and no stirrups. As a result of the absence of stirrups, able-bodied persons mounted with the help of a spear or staff, while old men were handed up by slaves. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Women rode only upon a pillion, and probably not very often in that way. The custom of nailing metal shoes upon the hoofs of horses was not known, but shoes made of metal, leather, or rushes were adjusted before passing over a specially bad road, and could later be removed when no longer needed. One bit found is quite simple, consisting of two bars joined by a double link, which probably belongs to the sixth century, though no doubt this type was in use for a long period; the other, probably of the fifth or fourth century, is very severe.

Xenophon in his treatise on Horsemanship (X, 6) describes this variety and explains its use in training horses. Branding was practised even for valuable animals. On a small amphora decorated with a picture of the Sun in his chariot, one of the horses is branded with a sun surrounded by rays. It was customary to muzzle horses when they were taken out for exercise or for some other purpose without a bridle. Probably the muzzles were usually made of leather, but bronze was employed on special occasions or by the wealthy. Two bronze muzzles, one of a simple, the other of a more elaborate form, are exhibited.

Greek boys received lessons in riding in the course of their athletic training, which was, of course, a preliminary military training as well. In Attica a troop of ephebes, young men in military service, patrolled the borders as a mounted guard. The decoration on a krater and a relief represent members of this troop in their short cloaks fastened on the shoulder and their broad-brimmed hats. A fine relief also represents an ephebe or one of the Diaskouri in this guise. Hunting deer and boars from horseback was a favorite sport which required skill in the rider, and riding-races of various types were a feature of the games. One of the Panathenaic amphorai was a prize for a horse-race at Athens, as the decoration shows. A bronze statuette of a horse at the head of the main staircase allows us to see the type of animal bred in Greece, and is at the same time a work of the greatest spirit and delicacy.

First Domesticated Horses

The first domesticated horses appeared around 6000 to 5000 years ago. The first hard evidence of mounted riders dates to about 1350 B.C. Uncovering information about ancient horsemen however is difficult. They left behind no written records and relatively few other groups wrote about them. For the most part they were nomads who had few possession, and never stayed in one place for long, making it difficult for archeologists — who have traditionally excavated ancient cities and settlements of settled people — to dig up artifacts connected with them.

For similar reasons it is difficult to work out how different horsemen groups interacted and how individuals within the group behaved. What little is known about group interaction has been learned mostly from the work of linguists. Most of what is known about their behavior is based on observations of modern groups or a hand full of descriptions by ancient historians. . Based on these sources, scholars believe that early nomadic horsemen lived in small groups, often organized by clan or tribe, and generally avoided forming large groups. Small groups have more mobility and flexibility to move to new pastures and water sources. Large groups are much more unwieldy and more likely to generate feuds and other internal problems. On the steppe there generally was enough land for all so the only time horsemen needed to unite was to face a common threat.

See Separate Article: EARLY HORSE DOMESTICATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Carts and Wagons in Ancient Greece

The main domesticated animals possessed by the Greeks and used for overland transportation were including horses, mules, donkeys and oxen. According to Encyclopedia.com: Of these animals, donkeys and mules were the most versatile and commonly used. They were either ridden, hitched to wheeled vehicles, or used as pack animals capable of carrying three or four times as much cargo as a human. Oxen were useful as draft animals when large loads had to be transported. They had greater pulling power and could be harnessed more efficiently than either horses or mules. The drawbacks to oxen were that they were slow (averaging about one mile per hour versus three miles per hour for mules), and they were also rare and expensive compared to donkeys and mules.

Horses were in frequently employed because they were expensive to obtain and raise; they were a privilege indulged in by the upper classes and used chiefly for racing and, to a lesser extent, warfare. Although far more fleet of foot than donkeys or mules, horses were difficult to control, more temperamental, less surefooted on mountain roads and tracks, and prone to injury.

The use of wheeled transport was considerably limited by difficult terrain and the poor quality of roads. Written sources and artistic images show that the Greeks had two-wheeled and four-wheeled carts that carried people or light cargo. These vehicles were generally pulled by donkeys or mules. Larger four-wheeled wagons, pulled by mules or oxen, were used for heavier loads. The basic Greek cart or wagon seems to have been little more than a wooden platform to which wooden or wickerwork sides were attached in order to keep the cargo from falling out. The wheels and axles were usually made of wood, and the heavier vehicles generally had solid wooden wheels, whereas chariots and lighter carts tended to have four-spoked wheels.

Wheeled vehicles were more commonly used for transportation in and around the cities and from ports to cities. Few Classical Greek cities were located right on the water because of worries about piracy and hostile raids. Even a city that traded extensively still had to transport cargo to and from its port. Wagons and carts also put to use doing this and were widely used by farmers in the Greek countryside, particularly for bringing their goods to market. On aspect of the city-state set up was the concentration of population and commerce in a single, central area, requiring farmers in the hinterlands to the market.

First Wheels and Wheeled Vehicles

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Bronze horse Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C. — the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — hows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Mule Wagon Described in The Iliad

Greek chariot

In Homer’s Iliad, written around 700 B.C., King Priam of Troy takes a wagonload of riches to Achilles. The wagon has a “carrying basket” — wickerwork siding attached to the wagon platform — and a single pole that runs between two mules. On the yoke is a ring which the “peg” (the end of the pole) slips into. The yoke is then lashed in place by leather thongs (“yoke lashing”) that are wrapped around the pole and around a knob on the yoke. The parts of the yoke that actually contact the mules is not mentioned but is assumed that there are a pair of yoke pads that go between the yoke and their shoulders, two thick straps that wrap around the front of their necks, and leather thongs that run behind their front legs.

“Well then, will you not get my wagon ready and be quick about it, and put all these things on it, so we can get on with our journey?” So he spoke, and they in terror at the old man’s scolding hauled out the easily running wagon for mules, a fine thing new-fabricated, and fastened the carrying basket upon it.

They took away from its peg the mule yoke made of boxwood with its massive knob, well fitted with guiding rings, and brought forth the yoke lashing (together with the yoke itself) of nine cubits and snugged it well into place upon the smooth-polished wagon-pole at the foot of the beam, then slipped the ring over the peg, and lashed it with three turns on either side to the knob, and afterwards fastened it all in order and secured it under a hooked guard. Then they carried out and piled into the smooth-polished mule wagon all the unnumbered spoils to be given for the head of Hektor, then yoked the powerful-footed mules who pulled in the harness and whom the Mysians gave once as glorious presents to Priam. [Source: Homer, The Iliad, translated by Richmond Lattrimore (Chicago: University of Chicago press, 1951).

Herodotus’s Ox-Cart Story

The 6th century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus relates the following story about using ox carts: Two young men of Argos … Cleobis and Biton … had enough to live on comfortably; and their physical strength is proved not merely by their success in athletics, but much more by the following incident. The Argives were celebrating the festival of Hera, and it was most important that the mother of the two young men should drive to the temple in her ox-cart; but it so happened that the oxen were late in coming back from the fields. [Source: Herodotus: The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt (Harmondsworth, U.K. & Baltimore: Penguin, 1954),

Her two sons, therefore, as there was no time to lose, harnessed themselves to the cart and dragged it along, with their mother inside, for a distance of nearly six miles, until they reached the temple. After this exploit which was witnessed by the assembled crowd, they had a most enviable death-t heaven-sent proof of how much better it is to be dead than alive.

Men kept crowding round them and congratulating them on their strength, and women kept telling the mother how lucky she was to have such sons, when, in sheer pleasure at this public recognition of her sons’ act, she prayed the goddess Hera, before whose shrine she stood, to grant Cleobis and Biton, who had brought her such honour, the greatest blessing that can fall to mortal man. After her prayer came the ceremonies of sacrifice and feasting; and the two lads, when all was over, fell asleep in the temple—and that was the end of them, for they never woke again.

Ships in Ancient Greece

Greek ships were built of wood and had shelters to protect the crew from the fierce Mediterranean sun. Over the open sea they traveled using hand-woven square sails. Some were also outfit with oars. The planks were usually made of a soft wood like sealed pine placed across tennons of live oak and fastened with oak pegs and sealed with sap and resin. The keels and steering oars were made from a hard wood such as oak.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the largest human-power ship ever was a catamaran galley with 4,000 rowers built in Alexandria Egypt in 210 B.C. for Ptolemy II. The vessel was 420 feet long and had 8 men on each 57-foot oar.

building a ship Anchors were damaged or lost so often that ships often carried several of them. Rock was used as ballast. Early anchors were made of stone. Anchors from the 5th century B.C. had a lead core and wooden bod and looked like a Christian cross with a pick ax head, perpendicular to the cross, at the bottom. The weight of the lead help drive the pick-ax part of the anchor into the sea bed.

Many ships had decorative “eyes” placed on the bow of the ship to help guide the ship through the sea and avoid trouble. They were generally made from marble and were found on both merchant ships and war vessels. The custom remains alive today. One the roads of Turkey, truck drivers have “eyes” painted on their bumpers that serve a similar purpose.

Book: “ Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK SHIPS: NAVIGATION, TYPES, SHIPWRECKS europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, Boat pictures from the Terra Romana Project / Forum Navis Romana

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024