SAILORS AND SHIPS IN ANCIENT ROME

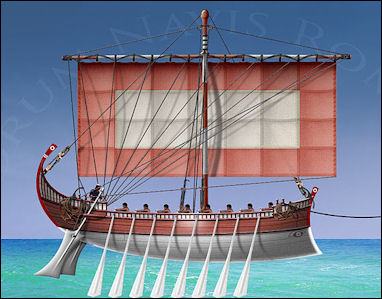

replica of a Roman military troop-transporting ship

Sailors served up to 26 years in the navy. Contrary to myth, the rowers on Roman ships were freemen not slaves. They were paid less than soldiers but still received a pretty good wage. Galley slaves were more common in the Middle Ages than in antiquity.

For members of non-citizen families, joining the navy was generally easier than joining the army and consequently young men from provinces such as Egypt were anxious to join up as a way of getting ahead. The job often meant pulling oars in a war galley and spending long periods in Rome away from one's family. The main reward was citizenship after discharge.

The Romans fought with triremes, combat galleys, with 200 oarsmen, arranged in three lines. Fleets with several hundred vessels were mobilized. A warship excavated from Pisa harbor featured an oak prow, covered with iron designed for ramming. The biggest expenses of the navy was building and maintaining these ships.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Navies of Rome” by Michael Pitassi (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 350 BC–AD 475" by Michael Pitassi (2020) Amazon.com;

“Warships of the Ancient World: 3000–500 BC” by Adrian K. Wood, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator) (2013) Amazon.com;

“Hjortspring: A Pre-Roman Iron Age Warship in Context” by Ole Crumlin-Pedersen and Athena Trakadas (2003) Amazon.com;

“Republican Roman Warships 509–27 BC” by Raffaele D’Amato and Giuseppe Rava (2015) Amazon.com;

“Imperial Roman Warships 27 BC–193 AD” by Raffaele D’Amato and Giuseppe Rava (2016) Amazon.com;

“Imperial Roman Warships 193–565 AD”, Illustrated, by Raffaele D’Amato and Giuseppe (2017) Amazon.com;

“Rome Seizes the Trident: The Defeat of Carthaginian Seapower & the Forging of the Roman Empire” by Marc G. DeSantis (2016) Amazon.com;

“Rome Versus Carthage: The War at Sea” by Christa Steinby (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic and Roman Naval Wars, 336 BC–31 BC”

by John D. Grainger Amazon.com;

“Sea of Flames: A thrilling account of the Battle of Actium” (2024) by Alistair Forrest Amazon.com;

“Actium 31 BC: Downfall of Antony and Cleopatra” by Si Sheppard , Christa Hook (Illustrator) (2009) Amazon.com;

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium”

by Barry Strauss Amazon.com;

“On Ancient Galleys: And Their Mode of Propulsion”

by William Schaw Lindsay (1871) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Oared Warships 399-30BC” by John Morrison (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

Ancient Greco-Roman Fighting Ships

Greek fighting ships were built of wood and had shelters to protect the crew from the fierce Mediterranean sun. Over the open sea they traveled using hand-woven square sails. The oars were mainly for powering and maneuvering the ships in battles. At the bow was a bronze ram that was used to batter and pierce enemy ship's sides and sink it. Their main objective was to clear away enemy ships so an army could land. [Source: Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine, January 1988]

Between 1150 B.C. and 850 B.C., the first ships with battering rams appeared and they shaped the way naval battles were fought for the next 1,500 years. The bow-based bronze rams transformed galleys from troop transports and coastal raiders into ships that were capable of fighting at sea. The "rams forced the construction of heavier vessels, and the tactics of ship-to-ship combat favored the development of faster and more maneuverable boats."

Biremes (galleys with double banks of oars) first appeared 700 B.C. Triremes (galleys with triple banks of oars) first appeared 500 B.C. but the cost of building them was so great that they were not widely used until around the time of Alexander (the 4th century B.C.). Not much is known about the designs of these ships other than what can be gleaned from historical accounts and few images on vases. No remains of a trireme have ever been found.

Triremes were used by Athenians to defeat the Persians at the Battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. A typical trireme is thought to have been a 118-foot-long vessel powered by sails and 170 oars mounted on three decks. The oars came in two lengths — 13 feet and 13 feet and 10 inches — and the oar holes were large enough for a man's head (a punishment that sometimes befell unruly oarsmen).

Triremes cruised at a speed estimated at between 7 and 12½ knots. They carried only 14 soldiers and a crew of 17 to go along with the 170 oarsmen. This because by the time they became widely used they were no longer troop carriers but were full-blown naval fighting ships. Triremes were made for day use only. There were no facilities on them for eating or sleeping.

See Separate Article: See Triremes Under ANCIENT GREEK NAVY: FIGHTING TRIREMES, OARSMEN AND SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Large Greco-Roman Ships

Roman-era, Greek-style cargo ship As time went the ships became larger and larger. Galleys rated as "fours," "fives," and "sixes" were introduced between 400 B.C. and 300 B.C. They were followed up by "16s," "20s" and "30s." The Emperor Ptolemy IV built a massive "40." The numbers refereed to the number pulling each triad of oars. Ships with more than three bank were built but ultimately they proved to be impractical.

Describing one of the largest boats, a 2nd century Greek wrote: "It was [420 feet] long, [58 feet] from gangway to plank and [72 feet] high to the prow ornament...It was double-prowed and double-sterned...During a trial run it took aboard over 4,000 oarsmen and 400 other crewmen, and on deck 2,850 marines."

In the late 1990s an English-Greek team built a 170-oar trireme at a cost of around $640,000. Held together with 20,000 tenons fastened with 40,000 oak pegs, it set sail with a an international crew of 132 men and 40 women. Describing, the team in action, Timothy Green wrote in Smithsonian, "the crew rowed together and sang together, getting up high spirits and up to seven knots.

Letters of Sailors in the Roman Navy

One new recruit from Egypt wrote his mother: "I arrived safely at Rome on Pachon 25 [May 20] and that I was assigned to Misenum. I don't know my ship yet...Don't worry about me? I've come to a good place."

Letter: “Apollinarius to Taesis, his mother and lady, many greetings! Before all I pray for your health. I myself am well, and make supplication for you before the gods of this place. I wish you to know, mother, that I arrived in Rome in good health on the 20th of the month Pachon, and was posted to Misenum, though I have not let learned the name of my company (kenturian); for I had not gone to Misenum at the time of writing this letter. I beg you then, mother, look after yourself and do not worry about me; for I have come to a fine place. Please write me a letter about your welfare and that of my brothers and of all your folk. And whenever I find a messenger I will write to you; never will I be slow to write. Many salutations to my brothers and Apollinarius and his children, and Karalas and his children. I salute Ptolemaeus and Ptolemais and her children and Heraclous and her children. I salute all who love you, each by name. I pray for your health. [Address:] Deliver at Karanis to Taesis, from her son Apollinarius of Misenum. [Source: Letter of a Recruit: Apollinarius, Select Papyri I (1932) #111 (II. A.D.), John Paul Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN)]

Ancient Greco-Roman Ship Rowers

Contrary to the popular myth Greek fighting ships were not manned by slaves, who were thought to be untrustworthy and expensive (they had be fed year-round even though a ship only operated about half the year). Instead they were manned by free citizens who sat on three levels.

Contrary to the popular myth Greek fighting ships were not manned by slaves, who were thought to be untrustworthy and expensive (they had be fed year-round even though a ship only operated about half the year). Instead they were manned by free citizens who sat on three levels.

The oars were secured with leather straps. The rowers had to learn to row in unison so their oars didn't collide. One rower said, "Because there are only nine inches between the blades any tiny discrepancy in a stroke caused one blade to hit the next and, and so on in a domino effect." When it is working well it was "like a centipede, with all oars moving beautifully."

The rowing stations at the center of the ship were best because if a oar is viewed as a lever and the oar hole is the fulcrum. According to the laws of mechanics the further one is away from the fulcrum the easier is to lift the object — or in the case of the oar, push the water.

Ancient Greco-Roman Sea Battles

In naval clashes, the Greeks preferred oared vessels over sailing ships because they were more maneuverable. Ships were used in conjunction with land forces to cut off coastal towns and keep large armies from landing. Almost all great naval battles from Salamis in 480 B.C. to Lepanto in and 1571 — were fought within sight of land. Maneuverability was an asset because naval clashes were essentially hand-to-hand land battles on water. Some of ships were outfitted with a battering ram bow and rowers who were stronger to propel their boat forward with enough force to sink with a broadside thrust on an enemy ship. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Sea battles and commerce usually only took place in the summer. During the winter the seas were too stormy and rough. The Battle of Salamis defeat of Persian invasion in 480 B.C. is one of the most important events in world history. See History Aristophanes wrote: "When there is a threat of war, you didn't sit quiet; but in a moment you be launching 300 ships and the city would be full of the hubbub of servicemen, or shouts for... wage-paying...Down in on the dockyard the air would be full of the planing of oars, the hammering of dowel pins, the fitting of oarports with leathers, or popes, bosn's, trills and whistles."

The Greeks mainly fought with triremes. Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Greece’s naval dominance did not last forever, and the trireme evolved. Modifications to the trireme as a design were spearheaded by various Mediterranean powers, and put to the test in the period when the successors of Alexander the Great fought for dominance in the late fourth and early third centuries B.C. By the time of the First Punic War in the mid-third century B.C., Romans and Carthaginians were fighting at sea using quadriremes and quinqueremes.[Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

When the Romans conquered Macedonia in 168 B.C., they were surprised to discover an ancient trireme, left abandoned in a shipyard for 70 years. They considered it a relic, but so beautifully made that they reused it. History’s final recorded battle relying on the descendants of the trireme was the Battle of Lepanto off western Greece on October 7, 1571 — more than 2,000 years after triremes first sailed. The Holy League coalition of Spain and many Italian city-states smashed the Ottoman fleet, killing nearly half their 67,000 men.

The Battle of Lepanto was one of the last naval conflicts in the West to rely heavily on human-driven galleys; subsequent naval conflicts would be dominated by sail-powered craft. The vast deployment of craft that marked naval battles in antiquity was also becoming a thing of the past. Nearly 700 galleys took part in the Battle of Ecnomus between Rome and Carthage in 256 B.C. A total of around 70 vessels took part in the Battle of Trafalgar of 1805.

Battle of the Aegates Islands

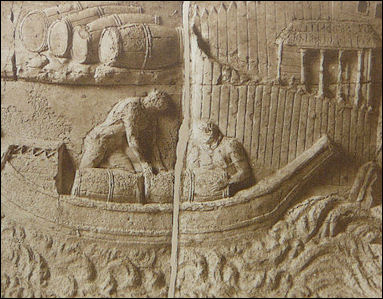

ship reliefs Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 B.C. was a naval battle fought between the fleets of Carthage and the Roman Republic during the First Punic War. It was a victory for the Romans that would lead to their domination in the years to come. Rome lacked a fleet — the ships it had possessed had been destroyed in a previous battle. Yet their enemies, the Carthaginian forces, did little to capitalise on this, allowing Rome to restore its strength and build a new stronger fleet. When the Carthaganians heard about this, they prepared their fleet for battle, and sailed to the Aegates Islands,” also called the Egadi Island, west of Sicily. “The Romans sailed out to meet them - but not before stripping their vessels of sails and masts to give them an advantage in rough sea conditions, By ramming into their enemy's ships and destroying half of the fleet, the Romans won a decisive victory. It was the last battle in the First Punic War, which had raged for 20 years as the two powers fought for supremacy over the western Mediterranean Sea. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology , Volume 65 Number 1, January/February 2012

“As Polybius tells it, the war came to a head in 242 B.C., with both powers exhausted and nearly broke after two decades of fighting. The Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca—the father of a later adversary of Rome, Hannibal—was pinned down on a mountaintop above the city of Drepana, now the Sicilian town of Trapani. As the Carthaginians assembled a relief force, the Romans scraped together the money for a fleet to cut them off. According to Polybius, in March 241 B.C., the two sides met in between the , a trio of rocky outcrops a few miles off the coast of Sicily. The clash brought hundreds of ships and thousands of men together in a battle that helped shape the course of history.

The battle lasted only a few hours.“While the Carthagnians were much more powerful on the water, the cunning Romans lay in wait trapping the Carthaginians and blocking off their sea route in a sudden victorious attack. Heather Ramsey of Listverse wrote: “With their 300 maneuverable ships, the Romans ambushed the enemy fleet and blocked their route. Only 250 of the 700 Carthaginian vessels were warships; the rest carried supplies. By the end of the swift battle, 70 Carthaginian ships were captured, 50 were sunk, and the remainder were able to escape.” Maybe 10,000 men were killed. [Source: Heather Ramsey, Listverse, March 4, 2015 ]

Battering Rams Key to Roman Victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands

Carthaginian naval ram

Roman battering rams are believed have played an important role in sinking the Carthaginian se ship. In waters around the islands where the battle took place archaeologist have found a dozen or so bronze battering rams, presumably used by ships to pummel each other. Some scholars had thought that ships were no longer ramming each other and that the rams were just for show. Jon Henderson, an underwater archaeologist at the University of Nottingham, told Archaeology magazine: 'But we have found bits of the enemy ships in some of the rams so it's very likely they were ramming each other.'

Heather Ramsey of Listverse wrote: “The underwater site is about 5 square kilometers and so far has yielded weapons, bronze helmets, tall Roman jars (called “amphorae”), and especially bronze battle rams. A ram is a part of a warship that extends from the bow to pierce the hull of an enemy ship. Until this site was discovered, only three rams had been found worldwide. Now, there are at least 14.

““Much of what we knew about ancient naval battles and ancient warships was based on historical text and iconography,” said archaeologist Jeffrey Royal. “We now have physical archaeological data which will significantly change our understanding. [These] rams were not just used as weapons, they were there to protect the ship. The discovery of these rams will help us learn more about the size of these ships, the way they were built, what materials were used as well as the economics of building a navy and the cost of losing a battle.” [Source: Heather Ramsey, Listverse, March 4, 2015 ]

“So far, we’ve learned that the warships were 30 percent smaller than originally believed. At only 28 meters (92 ft) long, it’s unlikely that they were triremes, warships propelled by three tiers of oarsmen on each side. The excessive height would have made the ships unstable. We’ve also discovered that a ram’s weight of 125 kilograms (275 lb) made it capable of slicing through a ship, not simply punching a small hole in its side. That means a damaged ship would shatter on the surface instead of sinking in one piece.”

Battle of Actium

The Battle of the Actium paved the way for Augustus (Octavian) to become the leader of Rome. While Antony and Cleopatra were trapped in Actium 400 ships and 80,000 infantrymen under Octavian's command approached Anthony's army from the north and cut of his supply lines in the south. Cleopatra reportedly was the one who urged Antony to make a final stand at sea. Cleopatra was put in charge of third of the fleet and ultimately showed that her military skill did not match her political skills

During the naval Battle of Actium in 31 B.C. the forces of Antony and Cleopatra were defeated by Octavian, whose navy was made up of smaller, faster ships that outmaneuvered the larger ships of Antony and Cleopatra's fleet after hard fighting and a lot of bloodshed. Many of the ships had battering rams, and many of the ships that sunk burned and were dragged down by their heavy battering rams. In 1993, objects believed to be from Anthony's fleet were discovered two miles off the west coast of Greece.

Before the battle had even begun, Cleopatra is said to have withdrawn her 60 ships, including her flagship containing Egypt's treasury. According to one account Antony abandoned his forces to pursue Cleopatra. In the run up to the battle Antony and Cleopatra staged a theater festival at Samos and neglected their supply lines.

RELATED ARTICLE: BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com

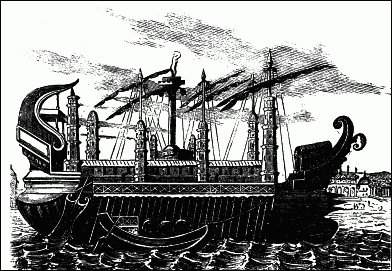

a great Roman fighting ship pictured in De Re Militari

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, and Roman-era Greek cargo ship and Triremis images from Forum Navis Romana Sven Littkowski

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024