SOLDIERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

armor A typical Roman soldier was in a unit with 80 men called a century strangely enough, with six centuries in cohort, and 10 cohorts in a legion, with about 30 legions in the entire Roman Empire. A man had be at least 169 centimeters (5feet 6½ inches) tall to join the army these days and 173 centimeters (5 feet 8 inches) to join to an elite regiment. In Roman times the average man was 157 centimeters (5 feet 2 inches). [Source: Daisy Dunn, The Telegraph, January 21, 2024]

In the Roman Republic, all Romans citizens were required to participate in the military. In the Roman Empire, when a professional army was in place, many soldiers were non-citizen volunteers who signed up in return for good pay, housing, status and booty from conquests. When they were discharged they became citizens. Even barbarians were recruited with these promises. The army’s greatest expense was its payroll. The expression "worth their salt" comes from Rome where soldiers were paid a salarium (salary) to buy salt.

The Romans managed create a professional army by paying soldiers enough so they were no longer tied to the land. Legionnaires were given a daily stipend. They served six to twenty years (averaging about ten). The completion of military service provided the soldier with citizenship not only for himself but for his entire family. The legionnaires were forbidden to marry, though some did illegally, and their families often "attached themselves to the camps." [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

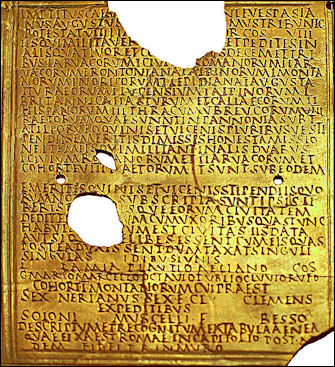

Military men were highly respected. After completion of their military service in a legion a soldier was rewarded with a bronze plate that had his name chiseled in it. This "diploma" meant that his marriage was sanctified by Roman law and all members of his family were Roman citizens. [Source: Timothy Foote, Smithsonian, April 1985]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN ARMY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ORGANIZATION OF THE ANCIENT ROMAN MILITARY: UNITS, STRUCTURE, DIVISIONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN LEGIONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN ARMY CAMPS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF ROMAN SOLDIERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TRAINING OF ROMAN SOLDIERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN WEAPONS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARMOR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN BATTLE PREPARATIONS AND PLANNING factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN BATTLE TACTICS: STRATEGY, MANUEVERS, FORMATIONS, SIEGES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN MILITARY IN BRITAIN: FRONTIERS, FORTS, CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND PUBS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

VINDOLANDA: ROMAN SOLDIER LIFE, TABLETS AND LETTERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Legion: Life in the Roman Army” by Richard Abdy (2024) Amazon.com;

“Legionary: The Roman Soldier's (unofficial) Manual” by Philip Matyszak (2009) Amazon.com

“A Week in the Life of a Roman Centurion” by Gary M. Burge (2015) Amazon.com;

“Soldiers and Ghosts” by J. E. Lendon (2005) Amazon.com;

“Gladius: The World of the Roman Soldier” by Guy de la Bédoyère (2020) Amazon.com

“Roman Military Clothing (1): 100 BC–AD 200 (Men-at-Arms)

by Graham Sumner (2002) Amazon.com;

“Roman Military Clothing (2): AD 200–400" by Graham Sumner (2003) Amazon.com;

“Roman Military Clothing (3): AD 400–640" by Raffaele D’Amato and Graham Sumner (2005) Amazon.com;

“In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2003) Amazon.com

“De Re Militari” by Vegetius, a 5th Century training manual in organization, weapons and tactics, as practiced by the Roman Legions Amazon.com

“The Roman Army at War: 100 BC-AD 200" by Adrian Goldsworthy (1996) Amazon.com

“Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome” by M. C Bishop (1989) Amazon.com

“The Complete Roman Army” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2003) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Army” (Blackwell) by Paul Erdkamp (2007) Amazon.com

“The Roman Army: The Greatest War Machine of the Ancient World” by Chris McNab 2010) Amazon.com

“The Complete Roman Legions “ by Nigel Pollard and Joanne Berry (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History” by Pat Southern (2006) Amazon.com

“Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2002) Amazon.com

Soldiers Versus Workers in Ancient Rome

military diploma Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The free-born citizens of Rome below the nobles and the knights may be roughly divided into two classes, the soldiers and the proletariat. The civil wars had driven them from their farms or had unfitted them for the work of farming, and the pride of race or the competition of slave labor had closed against them the other avenues of industry, numerous as these must have been in the world’s capital. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The best of these free-born citizens turned to the army, which had ceased to be composed of citizen-soldiers, called out to meet a special emergency for a single campaign, and disbanded at its close. From the time of the reorganization by Marius, at the beginning of the first century before our era, this was what we should call a regular army, the soldiers enlisting for a term of twenty years, receiving stated pay and certain privileges after an honorable discharge. In time of peace—when there was peace—they were employed on public works.

“The pay was small, perhaps forty or fifty dollars a year with rations in Caesar’s time, but this was as much as a laborer could earn by the hardest kind of toil, and the soldier had the glory of war to set over against the stigma of work, and hopes of presents from his commander and the privilege of occasional pillage and plunder. After he had completed his time, he might, if he chose, return to Rome, but many had formed connections in the communities where their posts were fixed and preferred to make their homes there on free grants of land, an important instrument in spreading Roman civilization.” |+|

Roman Soldiers and Their Weapons in the 2nd Century B.C.

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “The youngest of these troops are armed with a sword, light javelins, and a buckler. The buckler is both strongly made, and of a size sufficient for security. For it is of a circular form, and has three feet in the diameter. They wear likewise upon their heads some simple sort of covering; such as the skin of a wolf, or something of a similar kind; which serves both for their defense, and to point out also to the commanders those particular soldiers that are distinguished either by their bravery or want of courage in the time of action. The wood of the javelins is of the length of two cubits, and of the thickness of a finger. The iron part is a span in length, and is drawn out to such a slender fineness towards the point, that it never fails to be bent in the very first discharge, so that the enemy cannot throw it back again. Otherwise it would be a common javelin. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“The next in age, who are called the hastati, are ordered to furnish themselves with a complete suit of armor. This among the Romans consists in the first place of a shield of a convex surface; the breadth of which is two feet and a half; and the length four feet, or four feet and a palm of those of the largest size. It is composed of two planks, glued together, and covered first with linen, and afterwards with calves' skin. The extreme edges of it, both above and below, are guarded with plates of iron; as well to secure it against the strokes of swords, as that it may be rested also upon the ground without receiving any injury. To the surface is fitted likewise a shell of iron; which serves to turn aside the more violent strokes of stones, or spears, or any other ponderous weapon. After the shield comes the sword, which is carried upon the right thigh, and is called the Spanish sword. It is formed not only to push with at the point; but to make a falling stroke with either edge, and with singular effect; for the blade is remarkably strong and firm. To these arms are added two piles or javelins; a helmet made of brass; and boots for the legs. The piles are of two sorts; the one large, the other slender.

“Of the former those that are round have the breadth of a palm in their diameter; and those that are square the breadth of a palm likewise is a side. The more slender, which are carried with the other, resemble a common javelin of a moderate size. In both sorts, the wooden part is of the same length likewise, and turned outwards at the point, in the form of a double hook, is fastened to the wood with so great care and foresight, being carried upwards to the very middle of it, and transfixed with many close-set rivets, that it is sooner broken in use than loosened; though in the part in which it is joined to the wood, it is not less than a finger and a half in thickness. Upon the helmet is worn an ornament of three upright feathers, either red or black, of about a cubit in height; which being fixed upon the very top of the head, and added to their other arms, make the troops seem to be of double size, and gives them an appearance which is both beautiful and terrible. Beside these arms, the soldiers in general place also upon their breasts a square plate of brass, of the measure of a span on either side, which is called the guard of the heart. But all those who are rated at more than ten thousand drachmae cover their breasts with a coat of mail. The principes and the triarii are armed in the same manner likewise as the hastati; except only that the triarii carry pikes instead of javelins.”

Property Qualifications and Freeing Slaves to Fight as Roman Soldiers

Soldiers usually supplied their own uniforms, armor and weapons and for a rime had a property requirement. Cristian Violatti of Listverse wrote: “Military service was both a duty and a privilege of Roman citizens. In its early days, the Roman army was composed exclusively of citizens and organized on the basis of their social status (according to the weapons and equipment they could afford). The richest served in the cavalry, those not so rich served in the infantry, and men without property were excluded from the army. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 4, 2016 ]

master and slave

“After the Second Punic War (218–201 B.C.), this recruitment system became obsolete. Rome had become involved in longer and larger wars, and they needed a permanent military presence in the newly conquered territories. The property qualification was therefore reduced. During the second century B.C., property qualification was reduced even more. Then, in 107 B.C., Gaius Marius began to accept volunteers who had no property and were equipped at the expense of the government. (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 79)

Valerius Maximus wrote in “Memorable Deeds and Sayings,” VII.vi.1 in the A.D. 1st century: “For during the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) the Roman youth of military age having been drained by several unfavorable battles, the Senate, on the motion of the consul Tiberius Gracchus (consul in 215 and 213), decreed that slaves should be bought up out of public moneys for use in repulsing the enemy. After a plebiscite [(a vote of the Consilium Plebis] was passed on this matter by the people through the intervention of the Tribunes of the Plebs, a commission of three men was chosen to purchase 24,000 slaves, and having administered an oath to them that they would give zealous and courageous service and that they would bear arms as long as the Carthaginians were in Italy, they sent them to the camp. From Apulia and the Paediculi were also bought 270 slaves for replacements in the cavalry... The City, which up to this time had disdained to have as soldiers even free men without property added to its army as almost its chief support persons taken from slave lodgings and slaves gathered from shepherd huts.' [Source: Valerius Maximus “Memorable Deeds and Sayings,” VII.vi.1, John Paul Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN)]

Types of Men That Became Roman Soldiers

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari” (“Military Institutions of the Romans”): “Praefect of the Workmen: The legion had a train of joiners, masons, carpenters, smiths, painters, and workmen of every kind for the construction of barracks in the winter-camps and for making or repairing the wooden towers, arms, carriages and the various sorts of machines and engines for the attack or defense of places. They had also traveling workshops in which they made shields, cuirasses, helmets, bows, arrows, javelins and offensive and defensive arms of all kinds. The ancients made it their chief care to have every thing for the service of the army within the camp. They even had a body of miners who, by working under ground and piercing the foundations of walls, according to the practice of the Beffi, penetrated into the body of a place. All these were under the direction of the officer called the praefect of the workmen. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

Presumably describing a typical Roman soldier, Livy wrote in “Ab Urbe Condita” 42.34 (171 B.C.): “Citizens of Rome. I am Spurius Ligustinus, of the Tribe Crustumina, and I come of Sabine stock. My father left me half an acre of land and the little hut in which I was born and brought up. I am still living there today. As soon as I came of age, my father gave me his brother's daughter to wife, who brought nothing with her save her free birth and her chastity, together with a fertility which would be enough even for a wealthy home. We have six sons, and two daughters (both already married). Four of my sons have taken the toga of manhood; two are still under age. I joined the army in the consulship of Publius Sulpicius and Gaius Aurelius (Cotta) [200 B.C.], and I served two years in the ranks in the army which was taken across to Macedonia, in the campaign against King Philip [V, of Macedonia who died in 179]. In the third year Titus Quinctius Flamininus promoted me, for my bravery, to be centurion of the 10th maniple of hastati. After the defeat of King Philip and the Macedonians, when we had been brought back to Italy and demobilized, I immediately left for Spain as a volunteer with the consul Marcus Porcius [CATO, consul in 195 B.C.]. [Source: Livy, “Ab Urbe Condita” 42.34 (171 B.C.), John Paul Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN)]

“Of all the living generals, none has been a keener observer and judge of bravery than he, as is well known to those who through long military service have had experience of him and other commanders. This general judged me worthy to be appointed centurion of the 1st century of hastati. I enlisted for the third time, again as a volunteer, in the army sent against the Aetolians and King Antiochus. Manius Acilius [Glabrio, consul of 191] appointed me centurion of the first century of the principes. When King Antiochus had been driven out [Battle of Thermopylae] and the Aetolians had been crushed, we were brought back to Italy. And twice after that I took part in campaigns in which the legions served for a year. Thereafter I saw two campaigns in Spain, one with Quintus Fulvius Flaccus as Praetor [182, continued in office in 181 and 180], the other with Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus [father of the Gracchus brothers] in command [180]. I was brought back home by Flaccus with the others whom he brought back with him from the province for his Triumph, on account of their bravery. And I returned to Spain becaus eI was asked to do so by Tbierius Gracchus. Four times in the course of a few years I held the rank of Chief Centurion. Thirty four times I was rewarded for bravery by the generals. I have been given six civic crowns. I have completed 22 years of service in the army, and I am now over 50 years old. But even if I had not completed my service, and if my age did not give me exemption, it would still be right for me to be descharged, Publius Licinius, since I could give your four soldiers as my substitutes...' There was an official vote of thanks, and the Military Tribunes, on account of his bravery appointed him First Centurion of the First Legion. The other centurions withdrew their appeal and obediently responded to the call for conscription.”

Foot Soldiers in Roman Army

Roman foot soldiers that served in military units called legions were called legionaries. Elite soldiers were called Centurians. "The golden eagle which glittered in the front of the legion was the object of the fondest devotion," wrote Edward Gibbon in the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Each legion had its own symbol. The emblem of the 20th legion, for example, was the wild boar.

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari” (“Military Institutions of the Romans”): “Centuries and Ensigns of the Foot: We have observed that the legions had ten cohorts, the first of which, called the Millarian Cohort, was composed of men selected on account of their circumstances, birth, education, person and bravery. The tribune who commanded them was likewise distinguished for his skill in his exercises, for the advantages of his person and the integrity of his manners. The other cohorts were commanded, according to the Emperor's pleasure, either by tribunes or other officers commissioned for that purpose. In former times the discipline was so strict that the tribunes or officers abovementioned not only caused the troops under their command to be exercised daily in their presence, but were themselves so perfect in their military exercises as to set them the example. Nothing does so much honor to the abilities or application of the tribune as the appearance and discipline of the soldiers, when their apparel is neat and clean, their arms bright and in good order and when they perform their exercises and evolutions with dexterity. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

“The chief ensign of the whole legion is the eagle and is carried by the eagle-bearer. Each cohort has also its own peculiar ensign, the Dragon, carried by the Draconarius. The ancients, knowing the ranks were easily disordered in the confusion of action, divided the cohorts into centuries and gave each century an ensign inscribed with the number both of the cohort and century so that the men keeping it in sight might be prevented from separating from their comrades in the greatest tumults. Besides the centurions, now called centenarii, were distinguished by different crests on their helmets, to be more easily known by the soldiers of their respective centuries. These precautions prevented any mistake, as every century was guided not only by its own ensign but likewise by the peculiar form of the helmet of its commanding officers. The centuries were also subdivided into messes of ten men each who lay in the same tent and were under orders and inspection of a Decanus or head of the mess. These messes were also called Maniples from their constant custom of fighting together in the same company or division.”

Cavalry in Roman Army

Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “As the divisions of the infantry are called centuries, so those of the cavalry are called troops. A troop consists of thirty-two men and is commanded by a Decurion. Every century has its ensign and every troop its Standard. The centurion in the infantry is chosen for his size, strength and deXterity in throwing his missile weapons and for his skill in the use of his sword and shield; in short for his expertness in all the exercises. He is to be vigilant, temperate, accive and readier to execute the orders he receives than to talk; Strict in exercising and keeping up proper discipline among his soldiers, in obliging them to appear clean and well-dressed and to have their arms constantly rubbed and bright. In like manner the Decurion is to be preferred to the command of a troop for his activity and address in mounting his horse completely armed; for his skill in riding and in the use of the lance and bow; for his attencion in forming his men to all the evolutions of the cavaIry; and for his care in obliging them to keep their cuirasses, lances and helmets always bright and in good order. The splendor of the arms has no inconsiderable effect in striking terror into an enemy. Can that man be reckoned a good soldier who through negligence suffers his arms to be spoiled by dirt and rust? In short, it is the duty of the Decurion to be attentive to whatever concerns the health or discipline of the men or horses in his troop.

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “The cavalry is divided also into ten parts or troops. In each of these, three captains first are chosen; who afterwards appoint three other officers to conduct the rear. The first of the captains commands the whole troop. The other two hold the rank and office of decurions; and all of them are called by that name. In the absence of the first captain, the next in order takes the entire command. The manner in which these troops are armed is at this time the same as that of the Greeks. But anciently it was very different. For, first, they wore no armor upon their bodies; but were covered, in the time of action, with only an undergarment. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III:The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“In this method, they were able indeed to descend from their horses, or leap up again upon them, with greater quickness and facility; but, as they were almost naked, they were too much exposed to danger in all those engagements.The spears also that were in use among them in former times were, in a double respect, very unfit for service. First, as they were of a slender make, and always trembled in the hand, it not only was extremely difficult to direct them with exactness towards the destined mark; but very frequently, even before their points had reached the enemy, the greatest part of them were shaken into pieces by the bare motion of the horses. Add to this, that these spears, not being armed with iron at the lowest end, were formed to strike only with the point, and, when they were broken by this stroke, were afterwards incapable of any farther use.

“Their buckler was made of the hide of an ox, and in form was not unlike to those globular dishes which are used in sacrifices. But this was also of too infirm a texture for defense; and, as it was at first not very capable of service, it afterwards became wholly useless, when the substance of it had been softened and relaxed by rain. The Romans, therefore, having observed these defects, soon changed their weapons for the armor of the Greeks. For the Grecian spear, which is firm and stable, not only serves to make the first stroke with the point in just direction and with sure effect; but, with the help of the iron at the opposite end, may, when turned, be employed against the enemy with equal steadiness and force. In the same manner also the Grecian shields, being strong in texture, and capable of being held in a fixed position, are alike serviceable both for attack and for defense. These advantages were soon perceived, and the arms adopted by the cavalry. For the Romans, above all other people, are excellent in admitting foreign customs that are preferable to their own.”

Praetorian Guard: Rome’s Most Elite Soldiers

To support the imperial authority at home, and to maintain public order, Augustus organized a body of nine thousand men called the “praetorian guard,” which force was stationed at different points outside of Rome. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Cristian Violatti of Listverse wrote: “The Praetorian Guard was a specialized unit of the Roman army that acted as household troops to the emperor and his personal bodyguards. During the first century B.C., the Praetorian Guard occasionally got involved in the process of appointing new emperors. [Source: Cristian Violatti, Listverse, September 4, 2016 ]

“But as time went by, their involvement grew larger until they eventually got into a position where they were able to appoint, remove, and even murder Roman emperors. One incentive for murdering emperors and appointing new ones was a practice known as “the donative,” which was an economic reward that the Praetorian Guard received from the newly appointed emperor once the previous one was killed.

“This practice was one of the reasons why emperor succession became truly chaotic during the late history of the Western Roman Empire. Once the loyal protectors of the the head of the Roman government, the Praetorian Guard gradually and ironically turned into a corrupt and dangerous army unit that held significant control over the life of the emperors.

Roman Military Rewards, Honors and Promotions

Roman military diploma

Roman soldiers earned about 300 denarii in a year, which is less than many farm laborer who earned one denarius a day. Legionaries served for 25 years and had to be citizen to join. While this may sound more like a prison sentence than a job there were perks, if you make it to discharge, such as getting your marriage officially be recognized, and receiving a bonus. The retirement package was decent, but many soldiers didn’t live long enough to receive it and to aad insult to injury they had to pay for their funerals. [Source: Daisy Dunn, The Telegraph, January 21, 2024]

Romans encouraged the soldiers with rewards for their bravery. These were bestowed by the general in the presence of the whole army. The highest individual reward was the “civic crown,” made of oak leaves, given to him who had saved the life of a fellow-citizen on the battlefield. Other suitable rewards, such as golden crowns, banners of different colors, and ornaments, were bestowed for singular bravery. When a general slew the general of the enemy, the captured spoils (spolia opima) were hung up in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius. The highest military honor which the Roman state could bestow was a triumph,—a solemn procession, decreed by the senate, in which the victorious general, with his army, marched through the city to the Capitol, bearing in his train the trophies of war. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

On promotion in the legion, Flavius Vegetius Renatus wrote in “De Re Militari”: “Heaven certainly inspired the Romans with the organization of the legion, so superior does it seem to human invention. Such is the arrangement and disposition of the ten cohorts that compose it, as to appear one perfect body and form one complete whole. [Source: De Re Militari (Military Institutions of the Romans) by Flavius Vegetius Renatus (died A.D. 450), written around A.D. 390. translated from the Latin by Lieutenant John Clarke Text British translation published in 1767. Etext version by Mads Brevik (2001)]

A soldier, as he advances in rank, proceeds as it were by rotation through the different degrees of the several cohorts in such a manner that one who is promoted passes from the first cohort to the tenth, and returns again regularly through all the others with a continual increase of rank and pay to the first. Thus the centurion of the primiple, after having commanded in the different ranks of every cohort, attains that great dignity in the first with infinite advantages from the whole legion. The chief praefect of the Praetorian Guards rises by the same method of rotation to that lucrative and honorable rank. Thus the legionary horse contract an affection for the foot of their own cohorts, notwithstanding the natural antipathy existing between the two corps. And this connection establishes a reciprocal attachment and union between all the cohorts and the cavalry and infantry of the legion.

Salaries and Reward for Courageous Roman Soldiers

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “The method by which the young men are animated to brave all danger is also admirable. When an action has passed in which any of the soldiers have shown signal proofs of courage, the consul, assembling the troops together, commands those to approach who have distinguished themselves by any eminent exploit. And having first bestowed on every one of them apart the commendation that is due to this particular instance of their valor, and recounted likewise all their former actions that have ever merited applause, he then distributes among them the following rewards. To him who has wounded an enemy, a javelin. To him who has killed an enemy, and stripped him of his armor, if he be a soldier in the infantry, a goblet; if in the cavalry, furniture for his horse; though, in former times, this last was presented only with a javelin. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

“These rewards, however, are not bestowed upon the soldiers who, in a general battle, or in the attack of a city, wound or spoil an enemy; but upon those alone who, in separate skirmishes, and when any occasion offers, in which no necessity requires them to engage in single contest, throw themselves voluntarily into danger, and with design provoke the combat. When a city is taken by storm, those who mount first upon the walls are honored with a golden crown. Those also who have saved the lives of any of the citizens, or the allies, by covering them from the enemy in the time of battle, receive presents from the consul, and are crowned likewise by the persons themselves who have thus been preserved, and who, if they refuse this office, are compelled by the judgment of the tribunes to perform it.

Roman salt mine, the word salary is derived from the Latin word for salt

“Add to this, that those who are thus saved are bound, during the remainder of their lives, to reverence their preserver as a father, and to render to him all the duties which they would pay to him who gave them birth. Nor are the effects of these rewards, in raising a spirit of emulation and of courage, confined to those alone who are present in the army, but extended likewise to all the citizens at home. For those who have obtained those presents, beside the honor which they acquire among their fellow soldiers, and the reputation which immediately attends them in their country, are distinguished after their return, by wearing in all solemn processions such ornaments as are permitted only to be worn by those who have received them from the consuls as the rewards of their valor. They hang up likewise in the most conspicuous parts of their houses the spoils which they have taken, as a monument and evidence of their exploits. Since such, therefore, is the attention and the care with which the Romans distribute rewards and punishments in their armies, it is not to be thought strange that the wars in which they engage are always ended with glory and success.

“The military stipends are thus regulated. The pay of a soldier in the infantry is two obols by the day; and double to the centurions. The pay of the cavalry is a drachma. The allowance of corn to each man in the infantry consists of about two-third parts of an Attic bushel of wheat by the month. In the cavalry, it is seven bushels of barley, and two of wheat. To the infantry of the allies the same quantity is distributed as to that of the Romans: but their cavalry receives only one bushel and a third of wheat, and five of barley. The whole of this allowance is given without reserve to the allies. But the Roman soldiers are obliged to purchase their corn and clothes, together with the arms which they occasionally want, at a certain stated price, which is deducted by the quaestor from their pay.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024