Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ROMAN PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER

The Romans could be family-oriented ... While professing to be moral citizens governed by laws and proponents of efficiency and monogamy, many Romans pursued pleasure and indulgence. The Romans were famous for their desire to have a good time. One Roman politician wrote: “Alas and alack! What a nothing is man! We all shall be bones at the end of life’s span, so let us be jolly for as long as we can.”

Violence and torture were common. Young noblemen were obligated to seek revenge for any injustices or humiliations directed at their fathers. Not to carry out such vengeance was regarded as the worst calamity that could occur to a father and the most shameful thing a son could do.

One graffiti inscription from Rome reads: "Let's eat, drink, have fun; first comes life, then philosophy." Describing the impression one gets of Romans by reading their graffiti, Heather Pringle wrote in Discover magazine, “The world revealed is at one tantalizingly, achingly familiar, yet strangely alien, a society that both closely parallels our own in its heedless pursuit of pleasure and yet remains starkly at odds with our cherished value of human rights and dignity.”

Dr Peter Heather wrote for the BBC: “It is important to recognise two separate dimensions of 'Roman-ness' - 'Roman' in the sense of the central state, and 'Roman' in the sense of characteristic patterns of life prevailing within its borders. The characteristic patterns of local Roman life were in fact intimately linked to the existence of the central Roman state, and, as the nature of state. Roman elites learned to read and write classical Latin to highly-advanced levels through a lengthy and expensive private education, because it qualified them for careers in the extensive Roman bureaucracy.” [Source: Dr Peter Heather, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

Roman Etiquette of the Late Republic as Revealed by the Correspondence of Cicero (Classic Reprint) by Anna Bertha Miller (1874-1962) Amazon.com;

“Emotion, Restraint, and Community in Ancient Rome” by Robert Kaster Amazon.com;

“Gestures and Acclamations in Ancient Rome” by Professor Gregory S. Aldrete (1999) Amazon.com;

"Dining Posture in Ancient Rome: Bodies, Values, and Status" by Matthew B. Roller Amazon.com;

“Laughter in Ancient Rome: On Joking, Tickling, and Cracking Up” by Mary Beard (2014)

Amazon.com;

“A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Agora: Ancient Greek and Roman Humour”

by R Drew Griffith, Robert B Marks , et al. (2011) Amazon.com;

“Controlling Laughter: Political Humor in the Late Roman Republic” by Anthony Corbeill (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor” by Amy Richlin (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster” by Carlin A. Barton (1993) Amazon.com;

“Death in Ancient Rome” by Catharine Edwards (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Week in the Life of Rome” by James L. Papandrea (2019) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Common Values That Unified the Roman Empire

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill of the University of Reading wrote for the BBC: “The unified empire depended on common values, many of which could be described as 'cultural', affecting both the elite and the masses. Popular aspects of Graeco-Roman literary culture spread well beyond the elite, at least in the cities. Baths and amphitheatres also reached the masses. It has been observed that the amphitheatre dominated the townscape of a Roman town as the cathedral dominated the medieval town. [Source: Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

...and loving and sensitive... “The underlying brutality of the amphitheatre was compatible with their own system of values and the vision of the empire as an endless struggle against forces of disorder and barbarism. The victims, whether nature's wild animals, or the human wild animals - bandits, criminals, and the Christians who seemed intent on provoking the wrath of the gods - gave pleasure in dying because they needed to be exorcised. |::|

“There was also a vital religious element which exposed the limits of tolerance of the system. The pagan gods were pluralistic, and a variety of local cults presented no problem. The only cult, in any sense imposed, was that of the emperor. To embrace it was as sufficient a symbol of loyalty as saluting the flag, and rejecting it was to reject the welfare of all fellow citizens. |::|

“Christians were persecuted because their religion was an alternative and incompatible system (on their own declaration) which rejected all the pagan gods. Constantine, in substituting the Christian god for the old pagan gods, established a far more demanding system of unity. |::|

“We are left with a paradox. The Roman Empire set up and spread many of the structures on which the civilisation of modern Europe depends; and through history it provided a continuous model to imitate. Yet many of the values on which it depended are the antithesis of contemporary value-systems. It retains its hold on our imaginations now, not because it was admirable, but because despite all its failings, it held together such diverse landscape for so long.” |::|

Roman Humor and Jokes

The Latin adjective ridiculus, referred both to something that was laughable ( “ridiculous “ in our sense) and to something or someone who actively made people laugh. Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard said, “Whereas we moderns tend to think about what it is that makes people laugh, the Romans were much more interested in the joker than the laugher. That is borne out by the rich Latin vocabulary concerned with the makers of jokes compared with the fairly small one relating to laughter — which is mostly confined to cognates of the verb ridere, to laugh. There was, she said, a kind of anxiety about the joker. Laughter was seen as janus faced. The maker of a joke could easily find himself the butt of one. (This ties into that fact that it was not seen as a good thing to laugh at oneself.)

Beard wrote in the New Statesman: “For the Romans, blindness – not to mention threats of murder – was a definite no-go area for joking, though they treated baldness as fair game for a laugh (Julius Caesar was often ribbed by his rivals for trying to conceal his bald patch by brushing his hair forward, or wearing a strategically placed laurel wreath).” [Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, June 12, 2014]

Julia “was one of the few Roman women celebrated for her own quips (which were published after her death, risqué as some of them were). When asked how it was that her children looked liked her husband when she was such a notorious adulteress, she equally notoriously replied, “I’m a ship that only takes passengers when the hold is full”; in other words, risk adultery only when you’re already pregnant.”

...but they could also be... The elder Crassus, a stern, stoical politician was said only to laughed only once in his life — when he saw a donkey eating thistles. That made him laugh because it reminded him of the famous ancient saying: "Thistles are like lettuce to the lips of a donkey."

Some have said that Cicero “the guy famous for his self-serving pomposity and putting schoolboys to sleep “ was the wittiest and even the funniest Roman ever. His slave collected his jokes and published them in three volumes after his death.

Cicero once discussed a joke made to one Gaius Sextius, who had one eye. Gaius Sextius invites a friend to dinner, who replies, "All right then — I see you've got a place for another” — an apparent reference to the fact he has another place for an eye. Cicero admitted that it was not a good joke — it's the joke of a scurror (jester) and not the bon mot of a sophisticated, urbane orator such as himself.

One of the jokes that Quintilian praises beyond all others goes: It is the trial of Milo, accused of killing the infamous, wildly unpopular, colourful, controversial aristocrat Clodius (this is all late-Republican political meltdown stuff). Cicero was defending Milo, but he himself was being interrogated by the prosecution. The question came: What time did Clodius die? Cicero answered: "Sero."....That, dear non Latinists, means "late"; and also "too late". The pun is, then, that Clodius died late in the day; but also he should have been got rid of ages ago. Quintilian thought ths was outrageously funny. Beard said, “It was spontaneous, applied only to Clodius, and it was true. It wasn't the joke of a scurror, a jester, it was the joke of a refined, elite orator.”

Book: “Laughter in Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (University of California Press) 2014; Laughter: A study of cultural psychology from Homer to early Christianity by Stephen Halliwell (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

Joking Around Roman-Emperor-Style

Mary Beard wrote in the New Statesman: “Politicians must always manage their chuckles, chortles, grins and banter with care. In Rome that entailed, for a start, being a sport when it came to taking a joke, especially from the plebs. The first emperor, Augustus, even managed to stomach jokes about that touchiest of Roman topics, his own paternity. Told that some young man from the provinces was in Rome who was his spitting image, the emperor had him tracked down. “Tell me,” Augustus asked, “did your mother ever come to Rome?” (Few members of the Roman elite would have batted an eyelid at the idea of some grand paterfamilias impregnating a passing provincial woman.) “No,” retorted the guy, “but my father did, often.” [Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, June 12, 2014]

“Where Caligula might have been tempted to click his fingers and order instant execution, Augustus just laughed – to his lasting credit. The Romans were still telling this story of his admirable forbearance 400 years later. And, later still, Freud picked it up in his book on jokes, though attributing it now to some German princeling. (It was, as Iris Murdoch puts into the mouth of one of her angst-ridden characters in The Sea, The Sea, “Freud’s favourite joke”.)

Nero dressed as a woman

“It also entailed joining in the give-and-take with carefully contrived good humour and a man-of-the-people air The same Augustus once went to visit his daughter and came across her being made up, her maids plucking out the grey hairs one by one. Leaving them to it, he came back later and asked casually, “Julia, would you rather be bald or grey?” “Grey, of course, Daddy.” “Then why try so hard to have your maids make you bald?”

“Unlike Augustus, “bad” politicians repeatedly got the rules of Roman laughter wrong. They did not joke along with their subjects or voters, but at their expense. The ultimate origin of the modern whoopee cushion is, in fact, in the court of the 3rd-century emperor Elagabalus, a ruler who is said to have far outstripped even Caligula in luxury and sadism. He would apparently make fun of his less important dinner guests by sitting them on airbags, not cushions, and then his slaves would let out the air gradually, so that by the middle of the meal they would find themselves literally under the table.

“The worst imperial jokes were even nastier. In what looks like a ghastly parody of Augustus’s quip about Julia’s grey hairs, the emperor Commodus (now best known as the lurid anti-hero, played by Joaquin Phoenix, of the movie Gladiator) put a starling on the head of a man who had a few white hairs among the black. The bird took the white hairs for worms, and so pecked them out. It looked like a good joke, but it caused the man’s head to fester and killed him. “There were issues of control involved, too. One sure sign of a bad Roman ruler was that he tried to make the spontaneous laughter of his people obey his own imperial whim. Caligula is supposed to have issued a ban on laughter throughout the city after the death of his sister – along with a ban on bathing and family meals (a significant trio of “natural” human activities that ought to have been immune to political interference). But even more sinister was his insistence – the other way round – that people laugh against their natural inclinations. One morning, for instance, he executed a young man and forced the father to witness his son’s execution. That same afternoon he invited the father to a party and now forced him to laugh and joke. Why did the man go along with it, people wondered. The answer was simple: he had another son.

“Self-control also came into the picture. The dear old emperor Claudius (who was also renowned for cracking very feeble – in Latin, frigidus, “cold” – jokes) was a case in point. When he was giving the first public reading from his newly composed history of Rome, the audience broke down at the beginning of the performance because a very large man had caused several of the benches to collapse. The audience members managed to pull themselves together but Claudius didn’t; and he couldn’t get through his reading without cracking up all the time. It was taken as a sign of his incapacity.

Roman Humor and Politics

On humor and ancient Roman politics, Beard wrote in the Times of London, “Laughter was always a favourite device of ancient monarchs and tyrants, as well as being a weapon used against them. The good king, of course, knew how to take a joke. The tolerance of the Emperor Augustus in the face of quips and banter of all sorts was still being celebrated four centuries after his death. One of the most famous one-liners of the ancient world, with an afterlife that stretches into the twentieth century (it gets retold, with a different cast of characters but the same punchline, both in Freud and in Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea), was a joking insinuation about Augustus’ paternity. Spotting, so the story goes, a man from the provinces who looked much like himself, the Emperor asked if the man’s mother had ever worked in the palace. “No”, came the reply, “but my father did.” Augustus wisely did no more than grin and bear it. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009]

Elagabalus as the High

Priest of the Sun Tyrants, by contrast, did not take kindly to jokes at their own expense, even if they enjoyed laughing at their subjects. Sulla, the murderous dictator of the first century BC, was a well-known philogelos (“laughter-lover”), while schoolboy practical jokes were among the techniques of humiliation employed by the despot Elagabalus. He is said to have had fun, for example, seating his dinner guests on inflatable cushions, and then seeing them disappear under the table as the air was gradually let out. But the defining mark of ancient autocrats (and a sign of power gone — hilariously — mad) was their attempt to control laughter. Some tried to ban it (as Caligula did, as part of the public mourning on the death of his sister). Others imposed it on their unfortunate subordinates at the most inappropriate moments. Caligula, again, had a knack for turning this into exquisite torture: he is said to have forced an old man to watch the execution of his son one morning and, that evening, to have invited the man to dinner and insisted that he laugh and joke. Why, asks the philosopher Seneca, did the victim go along with all this? Answer: he had another son.

For a similar confusion underlies the story of one determined Roman agelast (“non-laugher”), the elder Marcus Crassus, who is reputed to have cracked up just once in his lifetime. It was after he had seen a donkey eating thistles. “Thistles are like lettuce to the lips of a donkey”, he mused (quoting a well-known ancient proverb) — and laughed. There is something reminiscent here of the laughter provoked by the old-fashioned chimpanzees’ tea parties, once hosted by traditional zoos (and enjoyed for generations, until they fell victim to modern squeamishness about animal performance and display). Ancient laughter, too, it seems, operated on the boundaries between human and other species. Highlighting the attempts at boundary crossing, it both challenged and reaffirmed the division between man and animal.

What Made the Ancient Greeks and Romans Laugh?

Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “In the third century BC, when Roman ambassadors were negotiating with the Greek city of Tarentum, an ill-judged laugh put paid to any hope of peace. Ancient writers disagree about the exact cause of the mirth, but they agree that Greek laughter was the final straw in driving the Romans to war. One account points the finger at the bad Greek of the leading Roman ambassador, Postumius. It was so ungrammatical and strangely accented that the Tarentines could not conceal their amusement.[Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009. Mary Beard is the author of “The Roman Triumph” published in 2007 and “Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, 2008". She is Classics editor of the TLS.]

The historian Dio Cassius, by contrast, laid the blame on the Romans’ national dress. “So far from receiving them decently”, he wrote, “the Tarentines laughed at the Roman toga among other things. It was the city garb, which we use in the Forum. And the envoys had put this on, whether to make a suitably dignified impression or out of fear — thinking that it would make the Tarentines respect them. But in fact groups of revellers jeered at them.” One of these revellers, he goes on, even went so far as “to bend down and shit” all over the offending garment. If true, this may also have contributed to the Roman outrage. Yet it is the laughter that Postumius emphasized in his menacing, and prophetic, reply. “Laugh, laugh while you can. For you’ll be weeping a long time when you wash this garment clean with your blood.”

Despite the menace, this story has an immediate appeal. It offers a rare glimpse of how the pompous, toga-clad Romans could appear to their fellow inhabitants of the ancient Mediterranean; and a rare confirmation that the billowing, cumbersome wrap-around toga could look as comic to the Greeks of South Italy as it does to us. But at the same time the story combines some of the key ingredients of ancient laughter: power, ethnicity and the nagging sense that those who mocked their enemies would soon find themselves laughed at. It was, in fact, a firm rule of ancient “gelastics” — to borrow a term (from the Greek gelan, to laugh) from Stephen Halliwell’s weighty new study of Greek laughter — that the joker was never far from being the butt of his own jokes.

joke from Philogelos

Ancient Greco-Roman Joke Book

On the only joke book to have survived from the ancient was a Roman-period work written in Greek. Beard wrote, “Known as the Philogelos, this is a composite collection of 260 or so gags in Greek probably put together in the A.D. fourth century but including — as such collections often do — some that go back many years earlier. It is a moot point whether the Philogelos offers a window onto the world of ancient popular laughter (the kind of book you took to the barber’s shop, as one antiquarian Byzantine commentary has been taken to imply), or whether it is, more likely, an encyclopedic compilation by some late imperial academic. Either way, here we find jokes about doctors, men with bad breath, eunuchs, barbers, men with hernias, bald men, shady fortune-tellers, and more of the colourful (mostly male) characters of ancient life. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009]

The "egghead", or absent-minded professor, is a particular figure of fun, along with the eunuch, and people with hernias or bad breath. "They're also poking fun at certain types of foreigners — people from Abdera, a city in Thrace, were very, very stupid, almost as stupid as [they thought] eggheads [were]," said Beard. Pride of place in the Philogelos, Beard wrote, goes to the “egg-heads”, who are the subject of almost half the jokes for their literal-minded scholasticism (“An egg-head doctor was seeing a patient. “Doctor”, he said, “when I get up in the morning I feel dizzy for 20 minutes.” “Get up 20 minutes later, then?”). After the “egg-heads”, various ethnic jokes come a close second. In a series of gags reminiscent of modern Irish or Polish jokes, the residents of three Greek towns — Abdera, Kyme and Sidon — are ridiculed for their “how many Abderites does it take to change a light bulb?” style of stupidity. Why these three places in particular, we have no idea. But their inhabitants are portrayed as being as literal-minded as the egg-heads, and even more obtuse. “An Abderite saw a eunuch talking to a woman and asked if she was his wife. When he replied that eunuchs can’t have wives, the Abderite asked, “So is she your daughter then?”And there are many others on predictably similar lines.

Beard said the Philogelos shows the Romans were not the "pompous, bridge-building toga wearers" they were often made out to be but rather were a race ready to laugh at themselves. Alison Flood of The Guardian wrote, “Beard's favourite joke is a version of the Englishman, Irishman, Scotsman variety, with a barber, a bald man and an absent-minded professor taking a journey together. They have to camp overnight, so decide to take turns watching the luggage. When it's the barber's turn, he gets bored, so amuses himself by shaving the head of the professor. When the professor is woken up for his shift, he feels his head, and says "How stupid is that barber? He's woken up the bald man instead of me." [Source: Alison Flood, guardian.co.uk, March 13 2009 ]

"It's one of the better ones," said Beard. "It has a nice identity resonance ... A lot of the jokes play on the obviously quite problematic idea in Roman times of knowing who you are." Another "identity" joke sees a man meet an acquaintance and say "it's funny, I was told you were dead". He says "well, you can see I'm still alive." But the first man disputes this on the grounds that "the man who told me you were dead is much more reliable than you". An ancient version of Monty Python's dead parrot sketch sees a man buy a slave, who dies shortly afterwards. When he complains to the seller, he is told: "He didn't die when I owned him."

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK CHARACTER, FRIENDSHIP AND HUMOR europe.factsanddetails.com

Philegelos joke

Sex Jokes Found on Mosaics in a Roman Public Toilet in Turkey

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Mosaics on the floor of 1,800-year-old public toilets in Antiochia ad Cragum, a city on the southern coast of Turkey, reveal some amusing sexual puns. The second-century Roman mosaics are based on ancient mythology and show Narcissus (from whom we get the term “narcissist”) preoccupied with his own penis. According to the myth, Narcissus, a beautiful young man, fell in love with his own reflection. In the latrine version Narcissus has a notably long nose (something ancient Romans didn’t consider beautiful), and when he gazes down into the water he is actually admiring his large penis rather than his nose. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 22, 2018]

In the second scene, Ganymede is having his genitals washed by a bird holding a sponge. According to Homer, Ganymede was the most beautiful mortal in the world. Zeus fell in love with him and kidnapped him to serve as cup-bearer among the immortals. In the mosaic Zeus is shown not as an eagle but a heron. Ganymede (who in ancient art is usually shown holding a stick and hoop) is holding a sponge known as a tersorium. This the same kind of sponge that, ordinarily, would have served, in the words of historian Stephen Nash, as a communal “toilet brush for your butt.” Heron-Zeus grasps a sponge in his beak and dabs at Ganymede’s penis. Michael Hoff, an archaeologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, told Live Science this month, “Instantly, anybody who would have seen that image would have seen the [visual] pun… Is it indicative of cleaning the genitals prior to a sex act or after a sex act? That's a question I cannot answer, and it might have been ambiguous then.” In either case the combination of sexual and scatological imagery in a bathroom context is highly suggestive.

The scientists who discovered the mosaics last summer told Live Science that they were stunned by the discovery. Hoff added that, while a certain literacy with ancient mythology is a prerequisite for understanding the mosaics, “bathroom humor is kind of universal as it turns out."

Scatological and sexual graffiti adorned the walls of public bathrooms (and elsewhere) in the ancient world. One from Pompeii reads “Apollinaris, doctor to the emperor Titus, had a good crap (cacavit) here!” Another example of ancient bathroom grafitto reads “don’t shit here.” And these are the tamer examples. The intriguing thing about the mosaics from Antioch ad Cragnum is that the sexualized jovial tone is by thoughtful design. Many ancient bathrooms were beautiful; with frescoes on the walls, sculptures in the corners and, sometimes, marble slabs for ‘toilet seats.’ Bathroom humor was a matter of taste and consideration.

Philegelos joke

Humor in Ancient Rome Was a Matter of Life and Death

Mary Beard wrote in the New Statesman: “One evening at a palace dinner party, in about 40AD, a couple of nervous aristocrats asked the emperor Caligula why he was laughing so heartily. “Just at the thought that I’d only have to click my fingers and I could have both your heads off!” It was, actually, a favourite gag of the emperor (he had been known to come out with it when fondling the lovely white neck of his mistress). But it didn’t go down well. [Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, June 12, 2014]

“Roman histories and biographies are full of cautionary tales about laughter, used and misused – told, for the most part, to parade the virtues or vices of emperors and rulers. But just occasionally we get a glimpse from the other side, of laughter from the crowd, from the underlings at court, or laughter used as a weapon of opposition to political power. Romans did sometimes resort to scrawling jests about their political leaders on their city walls. Much of their surviving graffiti, to be honest, concentrates on sex, trivia (“I crapped well here”, as one slogan in Herculaneum reads) and the successes of celebrity gladiators or actors. But one wag reacted to Nero’s vast new palace in the centre of Rome by scratching: “Watch out, citizens, the city’s turning into a single house – run away to Veii [a nearby town], unless the house gobbles up Veii, too.”

“But the most vivid image of the other side of political laughter comes from the story told by a young senator, Cassius Dio, of his own experiences at the Colosseum in 192 AD. He’d nearly cracked up, he explains, as he sat in the front row watching a series of gladiatorial games and wild beast hunts hosted by the ruling emperor Commodus. Commodus was well known for joining in these performances as an amateur fighter (that’s where Gladiator gets it more or less right). During the shows in 192, he had been displaying his “combat” skills against the wild beasts. On one day he had killed a hundred bears, hurling spears at them from the balustrade around the arena. On other days, he had taken aim at animals safely restrained in nets. But what nearly gave Dio the giggles was the emperor’s encounter with an ostrich.

“After he had killed the poor bird, Commodus cut off its head, wandered over to where Dio and his friends were sitting and waved it at them with one hand, brandishing his sword in the other. The message was obvious: if you’re not careful, you’ll be next for the chop. The poor young senator didn’t know where to put himself. It was, he claims, “laughter that took hold of us rather than distress” – but it would have been a death sentence to let it show. So he plucked a leaf from the laurel wreath he was wearing and chewed on it desperately to keep the giggles from breaking out.

“It’s a nice story, partly because we can all recognise the sensation that Dio describes. His anecdote also deals with laughter as a weapon against totalitarian regimes. Dio more or less boasts that he found the emperor’s antics funny and that his own suppressed giggles were a sign of opposition. What better than to say that the psychopathic tyrant was not scary but silly?Yet it cannot have been quite so simple. For all Dio’s bravura looking back on the incident from the safety of his own study, it is impossible not to suspect that sheer terror as much as ridicule lay behind that laughter. Surely Dio’s line would have been rather different if some burly thug of an imperial guard had challenged him on the spot to explain his quivering lips? My guess is that those frightened aristocrats at the court of Caligula would have laughed in terror (or politely) at the emperor’s murderous “joke”. But, back home safely, they would have told a bold and self-congratulatory story, much as Dio did: “Of course, we couldn’t help but laugh at the silly man . . . ! The truth is that, in politics as elsewhere, no one ever quite knows why anyone else is laughing – or maybe not even why they themselves are laughing.”

Roman Customs

Roman took off their sandals when they entered a shrine. They entered a house with the right foot first. To do otherwise could bring bad luck. The Ancient Egyptians, Asian, Greeks and Romans showed respect by kissing the hand, feet or hem of important people.

Roman took off their sandals when they entered a shrine. They entered a house with the right foot first. To do otherwise could bring bad luck. The Ancient Egyptians, Asian, Greeks and Romans showed respect by kissing the hand, feet or hem of important people.

The thumps up, thumbs down signs have been dated back to the Etruscans in 500 B.C. when the thumbs up sign was a signal to save a fighter’s life in a battle and thumps down meant death. The Romans adopted the same signs for their gladiator battles.

The custom of flipping a coin to make a decision was an early form of divination of a yes-no question that had been around since the time coins were invented in Lydia in the 7th century. The heads-tail custom has been traced back to 1st century Rome, where the head of Caesar on a coin signalled a victory for the decision-seeker. Marriage decisions and judicial matters were sometimes settled with the flip of a coin.

Romans believed that yawning expelled life forces. People were taught to cover their mouths not out politeness but rather to keep the life force from leaving their bodies.

Romans gave out invitation to parties. A wooden tablet found in Britain from the wife of a military commandeer to another woman read: "For my birthday party I send you my warm invitation to come to see us."

The House of the Moralist at Pompeii is so named because the owner wrote rules of etiquette for his neighbors and visitors on the walls of his house, including “Let water wash your feet clean” and “Take care of our linens.”

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN SUPERSTITIONS, DIVINATION AND ASTROLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

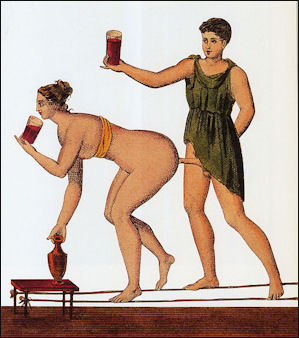

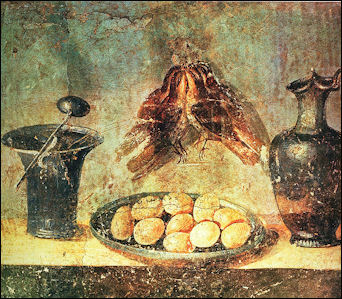

Eating Habits and Customs in the Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, people were given daily grain rations. Many people got their dinners from street vendors. Silverware sets of the wealthy unearthed in Pompeii and other places indicate that fancy meals consisted of many dishes, which in turn often consisted of fish, game, fruit and nuts. Ancient people largely ate with their hands. Sometimes they used knives and spoons. Romans had spoons, knives and drinking cups, but no forks. Sometimes they held a plate in their left hand and used their right hand to take food. Polite Romans lifted their food with three fingers so as not to dirty their ring finger and pinkie.

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “Dinner parties were the way the Roman aristocracy showed off their wealth and prestige, according to Michael MacKinnon, professor of archaeology at the University of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Status in the upper class was declared with the presentation of the meal, the rare spices, the dinnerware, he explained. “The wealthier you are the more you want to invest in display and advertising to your guests. Flash was perhaps more important than substance,” said MacKinnon. “Whole animals showed great wealth.” [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

“The lower classes ate to stay alive. Some historians believed the lower class was mostly vegetarian but that is not true, MacKinnon and Angela Trentacoste of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom said. The generally ate the same things the upper class did, but not the same cuts (think mutton versus lamp chops) and probably not in the same quantities. The rich reclined as they ate. Lower class Romans did not have fancy flatware, instead they used crude utensils. +/

“Because only the upper class had kitchens at home, other Romans bought food from street vendors, something like the lunch wagons of today. Mostly, MacKinnon said, they would put the food in large pots and make stews or a porridge. They might also boil the meat. Only the wealthy were able to broil or barbecue. +/

See Separate Article: EATING HABITS AND CUSTOMS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE: MEALS, COUCHES, UTENSILS europe.factsanddetails.com

Self Examination in the Ancient World

Food House of Julia in Pompeii Keeping a diary — journaling — is a way some people in the modern reflect on themselves and deal with stress and anxiety in their life. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: As it turns out, journaling is an ancient practice. There are, of course, different kinds of diaries — and were even thousands of years ago. There were travelogues like that written by early Christian female pilgrim Egeria. There were prison memoirs, like the one the Christian martyr Perpetua kept before her execution in the arena in Carthage in 203 A.D. And there were ‘wellness journals,’ like the dream journal/medical tourism diary that the orator Aelius Aristides kept in his Sacred Tales. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 29, 2018]

Texts like this were highly unusual: it was rare for people to commit their inner journey and personal experiences to paper and in solitude. More regularly the process of reviewing one’s day and taking stock of one’s actions took place via dialogue, through letter-writing with a friend, and in mental review. It’s a recognizable practice as early as Plato, who wrote that we should examine ourselves with great attention and that before we can become valuable members of society (as politicians, for example) we must, “before all else… attend to ourselves.”

The practice really took off among Roman Stoics in the first and second century A.D. The Emperor Marcus Aurelius and the Stoic philosopher Seneca were ardent believers in the examination of self. Before bedtime Seneca would review his day and everything that happened and ask himself how he had behaved and whether he could have responded to events that happened differently. Marcus Aurelius did the same kind of thing when he wrote his Meditations. Apparently Seneca’s habit was so entrenched that his wife knew not to disturb him as he performed it.

The goal of withdrawing into oneself and examining one’s motivations is to improve the self by fashioning it into the kind of person that one wants to be. Marcus Aurelius says that “your inner guide becomes impregnable when it withdraws into oneself” and that by ‘revering’ what is highest in ourselves (reason) we can achieve control of our passions (what we might call reckless emotions). Once we have done that we will no longer grow anxious about everyday affairs or be conflicted about the best course of action.

Inner dialogue is just one of a whole set of practices that ancient philosophers used to fashion and curate their selves. The French philosopher Michel Foucault called them “technologies of the self” and these technologies often included hiring a mentor who would advise the individual on the problematic aspects of their behavior. The mentor would be able to point out when someone lost their cool too easily, or was too self-indulgent. Once the aspiring philosopher had more self-control, the individual could begin to examine their behavior themselves through self-reflective writing and thought.

The purpose wasn’t just to make one a better person but to avoid what Greek writers called “distress.” Apparently many wealthy, educated Roman men struggled with feelings of anxiety. These were men who were already trying to live what we might call “self-aware” lives: they studied philosophy, they lived in moderation, and they tried to regulate their behaviors. And yet, all the same, they would feel psychic distress. Anxiety, it turns out, is not just a modern phenomenon that only affects “spoiled millennials;” it is actually a millennia-old condition. Roman authors diagnose different reasons for distress (many of which were tied to acquisitiveness) but self-examination through journaling was one of the technologies by which a person could hope to achieve what we might call ‘inner peace.’

Self-examination as practiced by wealthy, well-educated Greeks and Romans did not die out with the rise of Christianity. On the contrary, says Foucault, it was democratized and transformed into the verbal practice we call confession. With Christianity one would review not just one’s actions but even one’s thoughts with a priest. The penitential Christian would confess their sins before a priest by verbalizing, disclosing, and renouncing aspects of themselves and would, ultimately, feel reconnected to God and their own sense of self in the aftermath. The elite practices of examining the conscience we see in Seneca and Marcus Aurelius continued in the popular practices of medieval piety. As the philosopher Epicurus put it, “We must not hesitate to practice philosophy when we are young or grow weary of it when we are old. It is never too early or too late for taking care of one’s soul.”

Mos Maiorum

phallic figurine with a head of phalluses

The mos maiorum was an unwritten code pertaining to behavioral customs mostly derived from the traditions of the Romans’ ancestors. Translated as "ancestral custom" or "way of the ancestors" and is often compared with the English "mores", Mos maiorum was applied to private, political, and military life in ancient Rome. It was the core concept of Roman traditionalism and viewed as a dynamic complement to written law.

The Roman familia ("household") and Roman society were was hierarchical. These hierarchies were traditional and self-perpetuating and mos maiorum justified them and gave them support. The pater familias, or head of household, held absolute authority over his familia, which was both an autonomous unit within society and a model for the social order, but he was expected to exercise this power with moderation and to act responsibly on behalf of his family. The risk and pressure of social censure if he failed to live up to expectations was also a form of mos. [Source Wikipedia]

Michael Van Duisen wrote for Listverse: “Much like the Jews in the first song in Fiddler on the Roof, the Romans loved tradition and felt that moral decay would occur if they strayed too far from the ideals of the past. Therefore, obedience to the mos maiorum was seen as tantamount to maintaining a proper civilized Rome and was almost given legal standing. There were occasions where breaking tradition was seen as subversive; in the case of legislation, it was considered customary to bring proposals before the Senate. Any magistrate who neglected to perform this duty ran the risk of being labeled a traitor. Even with the strict punishment handed down for certain offenses, it was still considered unwritten. As such, the transmission of the mos maiorum from one generation to the next was said to be the duty of the family, especially the paterfamilias (head of the household).” [Source: Michael Van Duisen, Listverse, February 13, 2014]

Rome: A Nation of Warriors or Refined People?

William C. Morey wrote in “Outlines of Roman History”: “It is difficult for us to think of a nation of warriors as a nation of refined people. The brutalities of war seem inconsistent with the finer arts of living. But as the Romans obtained wealth from their wars, they affected the refinement of their more cultivated neighbors. Some men, like Scipio Africanus, looked with favor upon the introduction of Greek ideas and manners; but others, like Cato the Censor, were bitterly opposed to it. When the Romans lost the simplicity of the earlier times, they came to indulge in luxuries and to be lovers of pomp and show. They loaded their tables with rich services of plate; they ransacked the land and the sea for delicacies with which to please their palates. Roman culture was often more artificial than real. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

The survival of the barbarous spirit of the Romans in the midst of their professed refinement is seen in their amusements, especially the gladiatorial shows, in which men were forced to fight with wild beasts and with one another to entertain the people. In conclusion, we may say that by their conquests the Romans became a great and, in a certain sense, a civilized people, who appropriated and preserved many of the best elements of the ancient world; but who were yet selfish, ambitious, and avaricious, and who lacked the genuine taste and generous spirit which belong to the highest type of human culture.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum except the Philegelos jokes from the National Museum of Language

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024