Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ANCIENT GREEK CHARACTER

Based on ancient Greek mythology and art and stereotypes of modern Greeks, many people think of the ancient Greeks as a fun-loving people who indulged themselves in the good life: they drank lots of wine, cherished the sun and the sea, and participated in wild Dionysian festivals. Even so the Greeks regarded overindulgent people as possible traitors who might put their appetites before their loyalty to the state.

Important virtues included: style, grace, eloquence and self control. The Greeks looked down on conspicuous consumption and lack of self-control. The historical James Davidson wrote: "The Greeks imposed few rules from outside, but felt a civic responsibility to manage all appetites, to train themselves to deal with them, without trying to conquer them absolutely... The true gentleman manages his appetites. He is in charge of himself...Those who consume immoderately are the true slaves, being slaves to their appetites. It is the profligate and inconsistent who really engage in menial tasks as they are for ever running back and forth trying to fill their leaky jar with desire.”

The Greeks were very competitive. They were obsessed with battles and sports and even made speech making and poetry-reading into competitive events. The key piece of advise that Achilles was given by his father was: “Always to be the best and outdo the others.” In “Moralia”, Plutarch wrote that if a person has the intention to express loathing towards someone else, that person will feel slandered.

Greek had a deep sense melancholy and pessimism based on submission to fate. The historian Jacob Burckhard wrote : “The hero of myth scrupulously directs his whole life according to obscure sayings of the gods, but all vain; the predestined infants (Paris, Oedipus among ethers) left to die of exposure, are rescued and afterwards fulfill what was predicted for them.” Some Greeks believed it was best not to be born. The great sage Solon even went as far as saying: “Not one mortal is happy; everyone under the sun is unhappy.”

The Greek placed high value on bravery and loyalty. Epaminondas and Pelopidas, the Theban statesmen and generals, were celebrated for their devotion to each other. In a battle (B. C. 385) against the Arcadians, Epaminondas is said to have saved his friend's life. Plutarch in his Life of Pelopidas wrote: "Epaminondas and he were both born with the same dispositions to all kinds of virtues, but Pelopidas took more pleasure in the exercises of the body, and Epaminondas in the improvements of the mind; so that they spent all their leisure time, the one in hunting, and the pelestra, the other in learned conversation, and the study of philosophy. But of all the famous actions for which they are so much celebrated, the judicious part of mankind reckon none so great and glorious as that strict friendship which they inviolably preserved through the whole course of their lives, in all the high posts they held, both military and civil.... For being both in that battle, near one another in the infantry, and fighting against the Arcadians, that wing of the Lacedaemonians in which they were, gave way and was broken; which Pelopidas and Epaminondas perceiving, they joined their shields, and keeping close together, bravely repulsed all that attacked them, till at last Pelopidas, after receiving seven large wounds, fell upon a heap of friends and enemies that lay dead together. Epaminondas, though he believed him slain, advanced before him to defend his body and arms, and for a long time maintained his ground against great numbers of the Arcadians, being resolved to die rather than desert his companion and leave him in the enemy's power; but being wounded in his breast by a spear, and in his arm by a sword, he was quite disabled and ready to fall, when Agesipolis, king of the Spartans, came from the other wing to his relief, and beyond all expectation saved both their lives."

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek Civilization and Character; the Self-Revelation of Ancient Greek Society”

by Arnold Toynbee (1964) Amazon.com;

“A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Agora: Ancient Greek and Roman Humour”

by R Drew Griffith, Robert B Marks , et al. (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek Realities: Life and Thought in Ancient Greece” by Finley P. Hooper (1978) Amazon.com;

“Intimate Lives of the Ancient Greeks” by Stephanie L. Budin (2013) Amazon.com;

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

“The History of the Manners and Customs of Ancient Greece (Vol. 1-3): Tradition and Social Life in Antique” by James Augustus St. John (1795-1875) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“A Manual Of Grecian Antiquities: Being A Compendious Account Of The Manners And Customs Of The Ancient Greeks” by G H Smith (1832) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Society in Ancient Greece” by Jean-Pierre Vernant and Janet Lloyd (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: From the Archaic Age to the Arab Conquests” by G. E. M. de Ste. Croix (1981) Amazon.com;

“Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People” by Josiah Ober (1989) Amazon.com;

“Poverty in Ancient Greece and Rome: Realities and Discourses” (Routledge) by Filippo Carlà-Uhink, Lucia Cecchet, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and Greek Civilization” by Jacob Burckhardt (1902) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks” by H. Kitto (Penguin History) (Six books) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way” by Edith Hamilton (1930) Amazon.com;

“Sailing Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter “ by Thomas Cahill, Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Mask of Apollo” by Mary Renault, (1966), Novel Amazon.com;

“The Last of the Wine” by Mary Renault (1956), Novel Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History” by Sarah B. Pomeroy (1998) Amazon.com;

“Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece” by Robin Waterfield (2018) Amazon.com;

Friendship and Love in Ancient Greece

Simon May wrote in the Washington Post: “Only since the mid-19th century has romance been elevated above other types of love. For most ancient Greeks, for example, friendship was every bit as passionate and valuable as romantic-sexual love. Aristotle regarded friendship as a lifetime commitment to mutual welfare, in which two people become “second selves” to each other.” Homer said: “The difficulty is not so great to die for a friend, as to find a friend worth dying for.” [Source: Simon May, Washington Post, February 8, 2013. May, the author of “Love: A History,” is a visiting professor of philosophy at King’s College London]

“The idea of human love being unconditional is also a relatively modern invention. Until the 18th century, love had been seen, variously, as conditional on the other person’s beauty (Plato), her virtues (Aristotle), her goodness (Saint Augustine) or her moral authenticity (the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau). Even Saint Thomas Aquinas, perhaps the greatest of all Christian theologians, said we would have no reason to love God if He weren’t good.

Many of the great thinkers of love acknowledged its mortality. Aristotle said that love between two people should end if they are no longer alike in their virtues. Even Jesus seemed to suggest that God’s love for humanity isn’t necessarily eternal. After all, at the Last Judgment, the righteous will be rewarded with the Kingdom of God — with everlasting love — but those who did not act well in their lives will hear the heavenly judge say: “You that are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.” And Jesus adds: “These will go away into eternal punishment.”

Aristotle said: "Friendship is a thing most necessary to life, since without friends no one would choose to live, though possessed of all other advantages.”. . . “Since then his own life is, to a good man, a thing naturally sweet and ultimately desirable, for a similar reason is the life of his friend agreeable to him, and delightful merely on its own account, and without reference to any object beyond it; and to live without friends is to be destitute of a good, unconditioned, absolute, and in itself desirable; [57] and therefore to be deprived of one of the most solid and most substantial of all enjoyments." When asked ' What is Friendship ? ' Aristotle replied, 'One soul in two bodies."' [Source: Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902]

Symposium Speeches on the Value of Friendship

Edward Carpenter wrote in “Ioläus”: “In the Symposium or Banquet of Plato (428-347 B.C.), a supper party is supposed, at which a discussion on love and friendship takes place. The friends present speak in turn-the enthusiastic Phaedrus, the clear-headed Pausanias, the grave doctor Eryximachus, the comic and acute Aristophanes, the young poet Agathon; Socrates, tantalizing, suggestive, and quoting the profound sayings of the prophetess Diotima; and Alcibiades, drunk, and quite ready to drink more;-each in his turn, out of the fulness of his heart, speaks; and thus in this most dramatic dialogue we have love discussed from every point of view. and with insight, acumen, romance and humor unrivalled. Phaedrus and Pausanias, in the two following quotations, take the line which perhaps most thoroughly represents the public opinion of the day as to the value of friendship in nurturing a spirit of honor and freedom, especially in matters military and political. [Source: Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902] \=\

Speech of Phaedrus: "Thus numerous are the witnesses who acknowledge love to be the eldest of the gods. And not only is he the eldest, he is also the source of the greatest benefits to us. For I know not any greater blessing to a young man beginning life than a virtuous lover, or to the lover than a beloved youth. For the principle which ought to be the guide of men who would nobly live-that principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honor, nor wealth, nor any other motive is able to implant so well as love. Of what am I speaking? of the sense of honor and dishonor, without which neither states nor individuals ever do any good or great work. And I say that a lover who is detected in doing any dishonorable act, or submitting through cowardice when any dishonor is done to him bv another, will be more pained at being detected by his beloved than at being seen by his father, or by his companions, or by any one else.[Source: Symposium of Plato, trans. B. Fowett] \=\

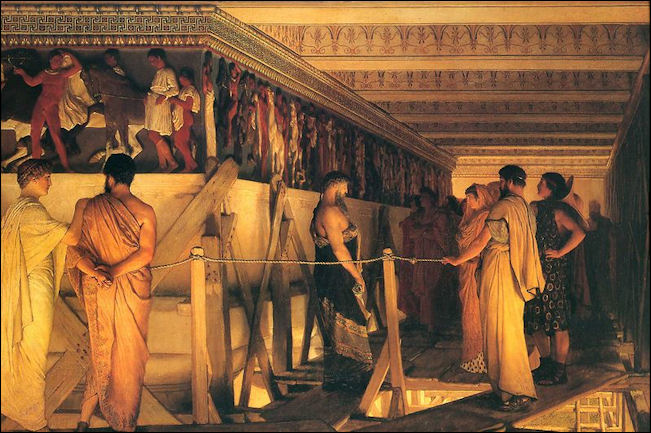

Lawrence Alma-Tadema painting of Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends

“The beloved, too, when he is seen in any disgraceful situation, has the same feeling about his lover. And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor, and emulating one another in honor; and when fighting at one another's side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world. For what lover would not choose rather to be seen by all mankind than by his beloved, either when abandoning his post or throwing away his arms? He would be ready to die a thousand deaths rather than endure this. Or who would desert his beloved, or fail him in the hour of danger? The veriest coward would become an inspired hero, equal to the bravest, at such a time- love would inspire him. That courage which, as Homer says, the god breathes into the soul of heroes, love of his own nature infuses into the lover."

“Speech of Pausanais: “In Ionia and other places, and generally in countries which are subject to the barbarians, the custom is held to be dishonorable; loves of youths share the evil repute of philosophy and gymnastics, because they are inimical to tyranny; for the interests of rulers require that their subjects should be poor in spirit, and that there should be no strong bond of friendship or society among them, which love above all other motives is likely to inspire, as our Athenian tyrants learned by experience." \=\

Speech of Aristophanes of Friendship and Love

Edward Carpenter wrote in “Ioläus”: “Aristophanes goes more deeply into the nature of this love of which they are speaking. He says it is a profound reality-a deep and intimate union, abiding after death, and making of the lovers "one departed soul instead of two.”But in order to explain his allusion to “the other half “it must be premised that in the earlier part of his speech he has in a serio-comic vein pretended that human beings were originally constructed double, with four legs, four arms, etc.; but that as a punishment for their sins Zeus divided them perpendicularly, “as folk cut eggs before they salt them,”the males into two parts, the females into two, and the hermaphrodites likewise into two-since when, these divided people have ever pursued their lost halves, and “thrown their arms around and embraced each other, seeking to grow together again.”And so, speaking of those who were originally males.[Source: Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902] \=\

Aristophanes said: “And when they reach manhood they are lovers of youth, and are not naturally inclined to marry or beget children, which they do, if at all, only in obedience to the law, but they are satisfied if they may be allowed to live with one another unwedded; and such a nature is prone to love and ready to return love, always embracing that which is akin to him. And when one of them finds his other half, whether he be a lover of youth or a lover of another sort, the pair are lost in an amazement of love and friendship and intimacy, and one will not be out of the other's sight, as I may say, even for a moment: they will pass their whole lives together; yet they could not explain what they desire of one another. For the intense yearning that each of them has towards the other does not appear to be the desire of lovers' intercourse, but of something else which the soul of either evidently desires and cannot tell, and of which she only has a dark and doubtful presentiment. [Source: Symposium of Plato, trans. B. Fowett] \=\

“Suppose Hephaestus, with his instruments, to come to the pair who are lying side by side and say to them, ' What do you people want of one another?' they would be unable to explain. And suppose further that when he saw their perplexity he said: ' Do you desire to be wholly one; always day and night to be in one another's company? for if this is what vou desire, I am ready to melt you into one and let you grow together, so that being two you shall become one, and while you live, live a common life as if you were a single man, and after your death in the world below still be one departed soul instead of two-I ask whether this is what you lovingly desire, and whether you are satisfied to attain this?'-there is not a man of them who when he heard the proposal would deny or would not acknowledge that this meeting and melting in one another's arms, this becoming one instead of two, was the very expression of his ancient need." \=\

Speech of Socrates on Love and Divine Beauty

Edward Carpenter wrote in “Ioläus”: “Socrates, in his speech, and especially in the later portion of it where he quotes his supposed tutoress Diotima, carries the argument up to its highest issue. After contending for the essentially creative, generative nature of love, not only in the Body but in the Soul, he proceeds to say that it is not so much the seeking of a lost half which causes the creative impulse in lovers, as the fact that in our mortal friends we are contemplating (though unconsciously) an image of the Essential and Divine Beauty; it is this that affects us with that wonderful “mania,”and lifts us into the region where we become creators. And he follows on to the conclusion that it is by wisely and truly loving our visible friends that at last, after long, long experience, there dawns upon us the vision of that Absolute Beauty which by mortal eyes must ever remain unseen. [Source: Edward Carpenter's “Ioläus,”1902 \=]

Socrates said: “He who has been instructed thus far in the things of love, and who has learned to see the beautiful in due order and succession, when he comes towards the end will suddenly perceive a nature of wondrous beauty . . . beauty absolute, separate, simple and everlasting, which without diminution and without increase, or any change, is imparted to the evergrowing and perishing beauties of all other things. He who, from these ascending under the influence of true love, begins to perceive that beauty, is not far from the end." [Source: Symposium of Plato, trans. B. Fowett] \=\

This is indeed the culmination, for Plato, of all existence-the ascent into the presence of that endless Beauty of which all fair mortal things are but the mirrors. But to condense this great speech of Socrates is impossible; only to persistent and careful reading (if even then) will it yield up all its treasures. \=\

Ancient Greek Humor

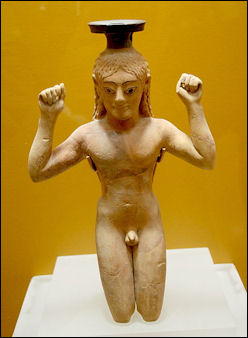

Comedic actor playing a slave

In 2019, archaeologists with the University of Nebraska announced the discovery of a somewhat bawdy second-century A.D. mosaic with humorous takes on famous Greek myths at the site of the city of Antiochia ad Cragum on the south coast of Turkey at what was a public latrine near a large bathhouse used by government officials who worked nearby. Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: One panel portrays Narcissus, the boy who fell in love with his own reflected image. Here he is infatuated with a rather more intimate part of his anatomy. Another panel shows Ganymede, cupbearer to the gods, offering up the ancient version of toilet paper. Project leader Michael Hoff explains that Romans weren’t squeamish about depicting bodily functions and sexuality. “One only has to visit the houses of Pompeii to see that images of sex and nudity were commonplace and visible to all, regardless of gender or status in society,” he says. Hoff adds that while the majority of Antiochia ad Cragum’s residents were not of Greek or Latin heritage, the mosaic demonstrates that Greek myths were almost universally understood in the far-reaching Mediterranean world. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2019]

Fragments of a Greek kylix (drinking cup) at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, dated to 480–470 B.C. and measuring 3.8 to 8.3 centimeters (1.5 to 3.5 inches) across, found at Naucratis, Egypt, features some amusing images. Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: A bored student passes notes. An exasperated teacher sighs. This scene would be familiar in any classroom around the world and across the ages. And while school scenes are uncommon in Greek vase painting, archaeologist Ollie Croker of the Museum of London believes that the painter of this drinking cup, an artist named Onesimos, clearly had an ancient version of these scholastic foes in mind. Croker says the scene of a disapproving teacher and a pupil surreptitiously examining a scroll is just one of several examples of humor in the cup’s imagery. [Source Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2023]

The scroll on the cup, which was found in Egypt, contains a phrase — “Muses who lead the chorus-leading hymn” — that cleverly slips in the name of the sixth-century B.C. poet Stesichorus. The text is written in a style called boustrophedon, or “as the ox plows,” in which alternating lines are written in opposite directions: left to right, then right to left. “Boustrophedon writing was very rarely used on Greek pottery,” Croker says, “and by the time this kylix was made, had fallen out of favor.” He believes that Onesimos’ anachronistic use of boustrophedon, which was popular during Stesichorus’ time, and the inclusion of the poet’s name recall a popular phrase — “You don’t know your Stesichorus.” Croker explains that this was a way of calling someone illiterate or not very clever, akin to “You haven’t read your Shakespeare.” “But, of course, you would have to be both literate and educated to get the joke,” he adds. An illiterate viewer would also have found humor on the vase, Croker suggests, in the pained visage of the teacher facing forward in an appeal for sympathy. It’s as if he wants you to know that his too-clever student’s joke is the last straw.

What Made the Ancient Greeks Laugh?

Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “In the third century BC, when Roman ambassadors were negotiating with the Greek city of Tarentum, an ill-judged laugh put paid to any hope of peace. Ancient writers disagree about the exact cause of the mirth, but they agree that Greek laughter was the final straw in driving the Romans to war. One account points the finger at the bad Greek of the leading Roman ambassador, Postumius. It was so ungrammatical and strangely accented that the Tarentines could not conceal their amusement.[Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009. Mary Beard is the author of “The Roman Triumph” published in 2007 and “Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, 2008". She is Classics editor of the TLS.]

perfume bottle The historian Dio Cassius, by contrast, laid the blame on the Romans’national dress. “So far from receiving them decently”, he wrote, “the Tarentines laughed at the Roman toga among other things. It was the city garb, which we use in the Forum. And the envoys had put this on, whether to make a suitably dignified impression or out of fear — thinking that it would make the Tarentines respect them. But in fact groups of revellers jeered at them.” One of these revellers, he goes on, even went so far as “to bend down and shit” all over the offending garment. If true, this may also have contributed to the Roman outrage. Yet it is the laughter that Postumius emphasized in his menacing, and prophetic, reply. “Laugh, laugh while you can. For you’ll be weeping a long time when you wash this garment clean with your blood.”

Despite the menace, this story has an immediate appeal. It offers a rare glimpse of how the pompous, toga-clad Romans could appear to their fellow inhabitants of the ancient Mediterranean; and a rare confirmation that the billowing, cumbersome wrap-around toga could look as comic to the Greeks of South Italy as it does to us. But at the same time the story combines some of the key ingredients of ancient laughter: power, ethnicity and the nagging sense that those who mocked their enemies would soon find themselves laughed at. It was, in fact, a firm rule of ancient “gelastics” — to borrow a term (from the Greek gelan, to laugh) from Stephen Halliwell’s weighty new study of Greek laughter — that the joker was never far from being the butt of his own jokes.

Ancient Greco-Roman Joke Book

On the only joke book to have survived from the ancient was a Roman-period work written in Greek. Beard wrote, “Known as the Philogelos, this is a composite collection of 260 or so gags in Greek probably put together in the A.D. fourth century but including — as such collections often do — some that go back many years earlier. It is a moot point whether the Philogelos offers a window onto the world of ancient popular laughter (the kind of book you took to the barber’s shop, as one antiquarian Byzantine commentary has been taken to imply), or whether it is, more likely, an encyclopedic compilation by some late imperial academic. Either way, here we find jokes about doctors, men with bad breath, eunuchs, barbers, men with hernias, bald men, shady fortune-tellers, and more of the colourful (mostly male) characters of ancient life. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009]

The "egghead", or absent-minded professor, is a particular figure of fun, along with the eunuch, and people with hernias or bad breath. "They're also poking fun at certain types of foreigners — people from Abdera, a city in Thrace, were very, very stupid, almost as stupid as [they thought] eggheads [were]," said Beard. Pride of place in the Philogelos, Beard wrote, goes to the “egg-heads”, who are the subject of almost half the jokes for their literal-minded scholasticism (“An egg-head doctor was seeing a patient. “Doctor”, he said, “when I get up in the morning I feel dizzy for 20 minutes.” “Get up 20 minutes later, then?”). After the “egg-heads”, various ethnic jokes come a close second. In a series of gags reminiscent of modern Irish or Polish jokes, the residents of three Greek towns — Abdera, Kyme and Sidon — are ridiculed for their “how many Abderites does it take to change a light bulb?” style of stupidity. Why these three places in particular, we have no idea. But their inhabitants are portrayed as being as literal-minded as the egg-heads, and even more obtuse. “An Abderite saw a eunuch talking to a woman and asked if she was his wife. When he replied that eunuchs can’t have wives, the Abderite asked, “So is she your daughter then?” And there are many others on predictably similar lines.

boar head oil lamp Beard said the Philogelos shows the Romans were not the "pompous, bridge-building toga wearers" they were often made out to be but rather were a race ready to laugh at themselves. Alison Flood of The Guardian wrote, “Beard's favourite joke is a version of the Englishman, Irishman, Scotsman variety, with a barber, a bald man and an absent-minded professor taking a journey together. They have to camp overnight, so decide to take turns watching the luggage. When it's the barber's turn, he gets bored, so amuses himself by shaving the head of the professor. When the professor is woken up for his shift, he feels his head, and says "How stupid is that barber? He's woken up the bald man instead of me." [Source: Alison Flood, guardian.co.uk, March 13 2009 ]

"It's one of the better ones," said Beard. "It has a nice identity resonance ... A lot of the jokes play on the obviously quite problematic idea in Roman times of knowing who you are." Another "identity" joke sees a man meet an acquaintance and say "it's funny, I was told you were dead". He says "well, you can see I'm still alive." But the first man disputes this on the grounds that "the man who told me you were dead is much more reliable than you". An ancient version of Monty Python's dead parrot sketch sees a man buy a slave, who dies shortly afterwards. When he complains to the seller, he is told: "He didn't die when I owned him."

In her quest to find out if people today found the same things funny as the Romans she told a a joke to one of her graduate classes, in which an absent-minded professor is asked by a friend to bring back two 15-year-old slave boys from his trip abroad, and replies "fine, and if I can't find two 15-year-olds I will bring you one 30-year-old," she found they "chortled no end". "They thought it was a sex joke, equivalent to someone being asked for two 30-year-old women, and being told okay, I'll bring you one 60-year-old. But I suspect it's a joke about numbers — are numbers real? If so two 15-year-olds should be like one 30-year-old — it's about the strange unnaturalness of the number system."

Beard, who discovered the title while carrying out research for a new book she's working on about humour in the ancient world, pointed out that when we're told a joke, we make a huge effort to make it funny for ourselves, or it's an admission of failure. "Are we doing that to these Roman jokes? Were they actually laughing at something quite different?"

Analysis of Ancient Greek Jokes

The most puzzling aspect of the jokes in the Philogelos is the fact that so many of them still seem vaguely funny. Across two millennia, their hit-rate for raising a smile is better than that of most modern joke books. And unlike the impenetrably obscure cartoons in nineteenth-century editions of Punch, these seem to speak our own comic language. In fact, the stand-up comedian Jim Bowen has recently managed to get a good laugh out of twenty-first-century audiences with a show entirely based on jokes from the Philogelos.

Why do ancient Greek jokes seem so modern? In the case of Jim Bowen’s performance, careful translation and selection has something to do with it (I doubt that contemporary audiences would split their sides at the one about the crucified athlete who looked as if he was flying instead of running). There is also very little background knowledge required to see the point of these stories, in contrast to the precisely topical references that underlie so many Punch cartoons. Not to mention the fact that some of Bowen's audience are no doubt laughing at the sheer incongruity of listening to a modern comic telling 2,000-year-old gags, good or bad. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009]

comedian actor with goat,

3d century BC But there is more to it than that. It is not, I suspect, much to do with supposedly “universal” topics of humour (though death and mistaken identity bulked large then as now). It is more a question of a direct legacy from the ancient world to our own, modern, traditions of laughter. Anyone who has been a parent, or has watched parents with their children, will know that human beings learn how to laugh, and what to laugh at (clowns OK, the disabled not). On a grander scale, it is — in large part at least — from the Renaissance tradition of joking that modern Western culture itself has learned how to laugh at “jokes”; and that tradition looked straight back to antiquity. One of the favourite gags in Renaissance joke books was the “No-but-my-father-did” quip about paternity, while the legendary Cambridge classicist Richard Porson is supposed to have claimed that most of the jokes in the famous eighteenth-century joke book Joe Miller’s Jests could be traced back to the Philogelos. We can still laugh at these ancient jokes, in other words, because it is from them that we have learned what “laughing at jokes” is.

This is not to say, of course, that all the coordinates of ancient laughter map directly onto our own. Far from it. Even in the Philogelos a few of the jokes remain totally baffling (though perhaps they are just bad jokes). But, more generally, Greeks and Romans could laugh at different things (the blind, for example — though rarely, unlike us, the deaf); and they could laugh, and provoke laughter, on different occasions to gain different ends. Ridicule was a standard weapon in the ancient courtroom, as it is only rarely in our own. Cicero, antiquity’s greatest orator, was also by repute its greatest joker; far too funny for his own good, some sober citizens thought.

There are some particular puzzles, too, ancient comedy foremost among them. There may be little doubt that the Athenian audience laughed heartily at the plays of Aristophanes, as we can still. But very few modern readers have been able to find much to laugh at in the hugely successful comedies of the fourth-century dramatist Menander, formulaic and moralizing as they were. Are we missing the joke? Or were they simply not funny in that laugh-out-loud sense? Discussing the plays in Greek Laughter, Halliwell offers a possible solution. Conceding that “Menandrian humour, in the broadest sense of the term, is resistant to confident diagnosis? (that is, we don’t know if, or how, it is funny), he neatly turns the problem on its head. They are not intended to raise laughs; rather “they are actually in part about laughter”. Their complicated “comic” plots, and the contrasts set up within them between characters we might want to laugh at and those we want to laugh with, must prompt the audience or reader to reflect on the very conditions that make laughter possible or impossible, socially acceptable or unacceptable. For Halliwell, in other words, Menander’s “comedy” functions as a dramatic essay on the fundamental principles of Greek gelastics.

On other occasions, it is not always immediately clear how or why the ancients ranked things as they did, on the scale between faintly amusing and very funny indeed. Halliwell mentions in passing a series of anecdotes that tell of famous characters from antiquity who laughed so much that they died. Zeuxis, the famous fourth-century Greek painter, is one. He collapsed, it is said, after looking at his own painting of an elderly woman. The philosopher Chrysippus and the dramatist Polemon, a contemporary of Menander, are others. Both of these were finished off, as a similar story in each case relates, after they had seen an ass eating some figs that had been prepared for their own meal. They told their servants to give the animal some wine as well — and died laughing at the sight.

The conceit of death by laughter is a curious one and not restricted to the ancient world. Anthony Trollope, for example, is reputed to have “corpsed” during a reading of F. Anstey’s comic novel Vice Versa. But what was it about these particular sights (or Vice Versa, for that matter) that proved so devastatingly funny” In the case of Zeuxis, it is not hard to detect a well-known strain of ancient misogyny. In the other cases, it is presumably the confusion of categories between animal and human that produces the laughter — as we can see in other such stories from antiquity.

Stephen Halliwell’s View on Greek Humor

actor as donkey

5th century BC In her review of “Greek Laughter” by Stephen Halliwell, Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “Halliwell insists that one distinguishing feature of ancient gelastic culture is the central role of laughter in a wide range of ancient philosophical, cultural and literary theory. In the ancient academy, unlike the modern, philosophers and theorists were expected to have a view about laughter, its function and meaning. This is Halliwell’s primary interest. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, February 2009]

His book offers a wide survey of Greek laughter from Homer to the early Christians (an increasingly gloomy crowd, capable of seeing laughter as the work of the Devil), and the introduction is quite the best brief overview of the role of laughter in any historical period that I have ever read. But Greek Laughter is not really intended for those who want to discover what the Greeks found funny or laughed at. There is, significantly, no discussion of the Philogelos and no entry for “jokes” in the index. The main focus is on laughter as it appears within, and is explored by, Greek literary and philosophical texts.

In those terms, some of his discussions are brilliant. He gives a clear and cautious account of the views of Aristotle — a useful antidote to some of the wilder attempts to fill the gap caused by the notorious loss of Aristotle’s treatise on comedy. But the highlight is his discussion of Democritus, the fifth-century philosopher and atomist, also renowned as antiquity’s most inveterate laugher. An eighteenth-century painting of this “laughing philosopher” decorates the front cover of Greek Laughter. Here Democritus adopts a wide grin, while pointing his bony finger at the viewer. It is a slightly unnerving combination of jollity and threat.

The most revealing ancient discussion of Democritus’s laughing habit is found in an epistolary novel of Roman date, included among the so-called Letters of Hippocrates — a collection ascribed to the legendary founding father of Greek medicine, but in fact written centuries after his death. The fictional exchanges in this novel tell the story of Hippocrates’encounter with Democritus. In the philosopher’s home city, his compatriots had become concerned at the way he laughed at everything he came across (from funerals to political success) and concluded that he must be mad. So they summoned the most famous doctor in the world to cure him. When Hippocrates arrived, however, he soon discovered that Democritus was saner than his fellow citizens. For he alone had recognized the absurdity of human existence, and was therefore entirely justified in laughing at it.

Under Halliwell’s detailed scrutiny, this epistolary novel turns out to be much more than a stereotypical tale of misapprehension righted, or of a madman revealed to be sane. How far, he asks, should we see the story of Democritus as a Greek equivalent of the kind of “existential absurdity” now more familiar from Samuel Beckett or Albert Camus? Again, as with his analysis of Menander, he argues that the text raises fundamental questions about laughter. The debates staged between Hippocrates and Democritus amount to a series of reflections on just how far a completely absurdist position is possible to sustain. Democritus’ fellow citizens take him to be laughing at literally everything; and, more philosophically, Hippocrates wonders at one point whether his patient has glimpsed (as Halliwell puts it) “a cosmic absurdity at the heart of infinity”. Yet, in the end, that is not the position that Democritus adopts. For he regards as “exempt from mockery” the position of the sage, who is able to perceive the general absurdity of the world. Democritus does not, in other words, laugh at himself, or at his own theorizing.

What Halliwell does not stress, however, is that Democritus’ home city is none other than Abdera — the town in Thrace whose people were the butt of so many jokes in the Philogelos. Indeed, in a footnote, he briefly dismisses the idea “that Democritean laughter itself spawned the proverbial stupidity of the Abderites”. But those interested in the practice as much as the theory of ancient laughter will surely not dismiss the connection so quickly. For it was not just a question of a “laughing philosopher” or of dumb citizens who didn’t know what a eunuch was. Cicero, too, could use the name of the town as shorthand for a topsy-turvy mess: “It’s all Abdera here”, he writes of Rome. Whatever the original reason, by the first century BC, “Abdera” (like modern Tunbridge Wells, perhaps, though with rather different associations) had become one of those names that could be guaranteed to get the ancients laughing.

Book: Greek Laughter: A study of cultural psychology from Homer to early Christianity by Stephen Halliwell (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

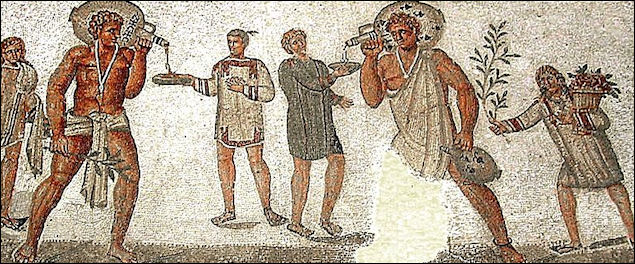

Roman-era mosaic of slaves

Ancient Greek Hospitality

If it was necessary to spend the night anywhere on a journey of several days, the widespread beautiful custom of hospitality which prevailed in ancient times, and made men regard every stranger as under the protection of Zeus, enabled them to find shelter; and, though this custom could not maintain itself in later times in its full extent, yet the effects of it still remained, and many people entered into a sort of treaty of hospitality with men in other towns, which was usually handed on to the descendants. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

By this they pledged themselves on the occasion of visits from members of one or the other family, to receive them in their houses and afford them the rights of hospitality; some little token of recognition previously agreed on — such as a little tablet, a ring broken into two halves, or something else of the sort — was used in such cases to legitimise the stranger. Sometimes whole districts entered into a league of this kind with one another, or one single rich man became the “guest-friend” of some foreign community, and entertained them when they came to his home. The service of the “guest-friend” was not always extended so far as to supply complete entertainment to the stranger as well as lodging; often he only supplied the lodging, the necessary coverings for the bed, and the use of the fire, which could not easily be procured, but in other respects left the guest, if he had brought servants with him, to provide for himself; some additional gifts of hospitality were usually sent him.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024