Home | Category: Religion / People, Marriage and Society

FUNERAL MONUMENTS IN ANCIENT GREECE

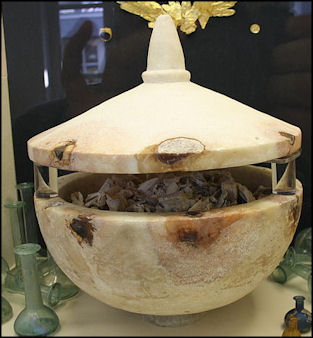

marble ossuary On the spot where the body or the ashes were buried, unless the remains were placed in some vault above the earth, they erected a funeral monument, which bore the name of the family and home of the deceased, sometimes in metrical form; and even gave details about his life and his virtues. This was usually decorated in an artistic manner. The commonest form was the “Stele,” which was sometimes a tall column, at others merely a horizontal gravestone, and represented the dead man in some occupation of daily life. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Sometimes families raised elaborate funerary monuments for the deceased but great tombs are associated more with the Romans than the Greeks. Funeral wreaths placed on tombs were hung with bronze leaves, terra-cotta berries, grapes, grasshoppers and cicadas.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The most lavish funerary monuments were erected in the sixth century B.C. by aristocratic families of Attica in private burial grounds along the roadside on the family estate or near Athens. Relief sculpture, statues, and tall stelai crowned by capitals, and finials marked many of these graves. Each funerary monument had an inscribed base with an epitaph, often in verse that memorialized the dead. A relief depicting a generalized image of the deceased sometimes evoked aspects of the person's life, with the addition of a servant, possessions, dog, etc. On early reliefs, it is easy to identify the dead person; however, during the fourth century B.C., more and more family members were added to the scenes and often many names were inscribed, making it difficult to distinguish the deceased from the mourners. Like all ancient marble sculpture, funerary statues and grave stelai were brightly painted, and extensive remains of red, black, blue, and green pigment can still be seen. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Many of the finest Attic grave monuments stood in a cemetery located in the outer Kerameikos, an area on the northwest edge of Athens just outside the gates of the ancient city wall. The cemetery was in use for centuries—monumental Geometric kraters marked grave mounds of the eighth century B.C., and excavations have uncovered a clear layout of tombs from the Classical period, as well. At the end of the fifth century B.C., Athenian families began to bury their dead in simple stone sarcophagi placed in the ground within grave precincts arranged in man-made terraces buttressed by a high retaining wall that faced the cemetery road. Marble monuments belonging to various members of a family were placed along the edge of the terrace rather than over the graves themselves.” \^/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Vergina: the Royal Tombs” by Manolis Andronicus (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Furniture and Furnishings of Ancient Greek Houses and Tombs”

by Dimitra Andrianou (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Burial Customs of the Ancient Greeks” by Frank Pierrepont Graves (1869-1956) Amazon.com;

“Greek Burial Customs” by Donna Kurtz (1978); Amazon.com;

“The Greek Way of Death” by Robert Garland (1985) Amazon.com;

“Mortuary Variability and Social Diversity in Ancient Greece: Studies on Ancient Greek Death and Burial” by Nikolas Dimakis and Tamara M. Dijkstra (2020) Amazon.com;

“Death in the Greek World: From Homer to the Classical Age” by Maria Serena Mirto and A.M. Osborne (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece” by Sarah Iles Johnston (1999) Amazon.com;

“Underworld Gods in Ancient Greek Religion” by Ellie Mackin Roberts (2022) Amazon.com;

“Greek & Roman Hell: Visions, Tours and Descriptions of the Infernal Otherworld” by Eileen Gardiner, Homer, Hesiod, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife” by Bart D. Ehrman Amazon.com ;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

Images on Funerary Stele

On a relief on a funerary stele A boy might be seen playing with his ball, and a girl with her doll; a young man holds his quoit; a strong warrior stands fully armed as though ready to depart; a countryman accompanied by his faithful dog, leans on his knotted stick; a young wife sits near her work-basket or gazes with pleasure at her ornaments, like the one represented on the relief, where the lady seems to be taking a ring from a jewel case held for her by her attendants; others represent the dead person alone or with others, not engaged in any occupation, but in some simple natural attitude, like the two women on the stone; others suggest death, since the relations are taking leave of a member of a family. On one it is the mother who is dying, and the smallest of the children is creeping up to her, or they are holding out to her a child still wrapped in swaddling clothes for her last kiss; the husband steps to his wife, who is resting in an easy chair, and gives her his hand for a last farewell, with an expression of sorrow mingled with self-control. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On some tombstones of a longer shape the family meal is represented; the husband lies on the couch, the wife sits near him, the children are pressing around them, and even the faithful animals, the dog and favorite horse, are not forgotten. This subject is a very common one; sometimes it is a simple scene from daily life, sometimes the master is represented in a more heroic attitude as already dead, and his relations are paying the departed the fitting honour and adoration. There seems to be little attempt at representing real portraits on most Greek tombstones; they are ideal types, often of extraordinary beauty, now and then, perhaps, with some slight resemblance to the dead, but by no means realistic portrait statues. But whether it is a scene from real life that is represented by art, or the bitter last farewell, or whether it is any hint of the life in a future state, which last is by no means uncommon, these reliefs are always distinguished by their moderation in the expression of pain, and a peaceful feeling of calm and worthy expression of sorrow, which can but have an elevating effect even on those who have grown up in the views of Christianity. This is the case even where some simple stonemason has roughly expressed in stone the thought of parting and reunion; how much more, then, in those magnificent creations of the finest period of Attic art to which the examples represented above belong.

There were many other shapes adopted for these tombstones. Very often the stelai were decorated with painting instead of reliefs; in some the surface was extended and the background hollowed out, which gave them an altar-like character, and they were often framed in correspondingly by pillars and gables. Occasionally the stones bore the shape of a vase, especially of the oil-flask, so important in its association with death, and this, too, might be decorated with sculpture. Sometimes they set low columns of round or square shape on the grave, on which they often represented a siren, who had a special significance as singer of mourning songs; sometimes whole statues — ideal pictures or portraits of the deceased — were placed there, though the custom was more common in the Hellenic period than in the best ages of art.

Tombs in Corinth

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” Book II: Corinth (A.D. 160): “When you have come from the Corinthian to the Sicyonian territory you see the tomb of Lycus the Messenian, whoever this Lycus may be; for I can discover no Messenian Lycus who practised the pentathlon1 or won a victory at Olympia. This tomb is a mound of earth, but the Sicyonians themselves usually bury their dead in a uniform manner. They cover the body in the ground, and over it they build a basement of stone upon which they set pillars. Above these they put something very like the pediment of a temple. They add no inscription, except that they give the dead man's name without that of his father and bid him farewell. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

After the tomb of Lycus, but on the other side of the Asopus, there is on the right the Olympium, and a little farther on, to the left of the road, the grave of Eupolis, 1 the Athenian comic poet. Farther on, if you turn in the direction of the city, you see the tomb of Xenodice, who died in childbirth. It has not been made after the native fashion, but so as to harmonize best with the painting, which is very well worth seeing. Farther on from here is the grave of the Sicyonians who were killed at Pellene, at Dyme of the Achaeans, in Megalopolis and at Sellasia.1 Their story I will relate more fully presently. By the gate they have a spring in a cave, the water of which does not rise out of the earth, but flows down from the roof of the cave. For this reason it is called the Dripping Spring. On the modern citadel is a sanctuary of Fortune of the Height, and after it one of the Dioscuri. Their images and that of Fortune are of wood.

“On the stage of the theater built under the citadel is a statue of a man with a shield, who they say is Aratus, the son of Cleinias. After the theater is a temple of Dionysus. The god is of gold and ivory, and by his side are Bacchanals of white marble. These women they say are sacred to Dionysus and maddened by his inspiration. The Sicyonians have also some images which are kept secret. These one night in each year they carry to the temple of Dionysus from what they call the Cosmeterium (Tiring-room), and they do so with lighted torches and native hymns.”

Bronze Mermaid Bed and Tombs of the Elite in Ancient Greece

Richer people had special vaults, which were either constructed by hollowing out the rocky ground below or above the earth, or by the artificial building up of a tumulus. The curious tholos buildings of Mycenae, Orchomenus, Attica, etc., are generally supposed now to be nothing but large vaults of this description; and, indeed, throughout the whole of Greece, Sicily, and Lower Italy, numerous tombs, either vaulted out of the rock or constructed of large blocks of stone, have been discovered, not to speak of the temples and towers which are chiefly found in Asia Minor, and usually appear to be due to non-Greek origin or influence. In these vaults, which often served for whole families, they laid their dead, either in coffins or without them, merely in their grave clothes, generally resting on a flat stone. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

One Attic vase picture represents the dead man in his tomb, the vaulting of which the painter has imitated, wrapped in a white cloth, a cushion under his head; fillets hang down from above. In Attica it was the custom to place the bodies so that their heads turned to the west and their feet to the east, while the opposite position was usual at Megara, where the customs differed in other ways, and three or four corpses were sometimes put in the same coffin.

In June 2023, archaeologists announced that they had unearthed the 2,100-year-old burial of a woman lying on a bronze “mermaid” bed near the city of Kozani in northern Greece. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science; Depictions of mermaids decorate the posts of the bed. The bed also displays an image of a bird holding a snake in its mouth, a symbol of the ancient Greek god Apollo. The woman's head was covered with gold laurel leaves that likely were part of a wreath, Areti Chondrogianni-Metoki, director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Kozani, told Live Science.[Source Owen Jarus, Live Science June 3, 2022]

It is presumed the woman was a member of the elite. The wooden portions of the bed have decomposed. Gold threads, possibly from embroidery, were found on the woman's hands, Chondrogianni-Metoki said. Additionally, four clay pots and a glass vessel were buried alongside the remains. No other people were buried with her. This bronze is plain looking, and has a rectangular bronze headboard on both ends. It has several wooden slats. The legs are made out of several knobbly bits of bronze, but nothing intricate. A mermaid head within a circle of bronze was found on the bed.

Tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s Father

In November 1977, Dr. Manolis Andronicos, an archaeologist at the University of Thessalonika unearthed a tomb under a mound in Vergina (40 kilometers west of Thessalonika, Greece) that is believe belonged to Philip II or Philip III. [Source: Manolis Andronicos, National Geographic, July 1978]

No inscription or definitive proof was found that linked the tomb to Philip II. Evidence that kinked the tomb to him included the discovery in the tomb of an ivory head thought to be a likeness of Philip and a diadem associated with Macedonian royalty, different size leg armor (possibly an accommodation to Philip II's bad leg), the high value of the objects and the dating of the objects to the time of Philip II reign. Evidence that refutes the claim are tooth remains usually associated with a man in his 30s (Philip II was 46 when he died).

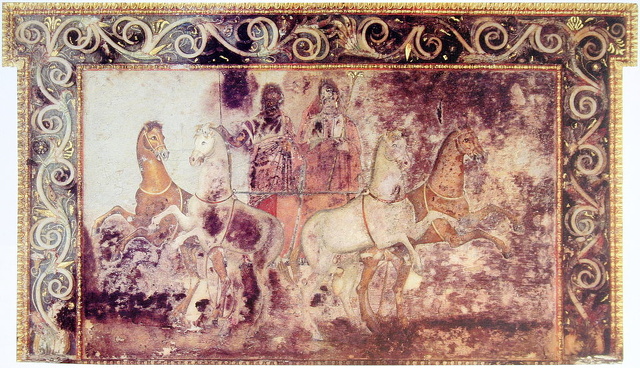

The tomb was very deep (23 feet under the ground), presumably to foil grave robbers. It was a barrel- vaulted structure with extraordinary Greek wall paintings with images of Pluto, god of the Underworld , abducting Persephone and a hunting scene with five horsemen with dogs and three hunters with spears pursuing wild boar and lions. These images unfortunately faded after they were exposed to sunlight and air.

Among the he objects found in the tomb were a marble sarcophagus, a large golden casket, a gold larnax (small casket) with a Macedonian star that contained cremated remains, a royal wreath of golden acorns and oak leaves, a gold-and-silver diadem, a golden quiver, purple fabric thread with gold, a perforated bronze lantern, weapons, silver vessels, bronze vessels, bronze armor, an iron helmet, a sword, scepter, sandals, a shield," spear points, javelins, golden lion heads, and sculpture, possibly of Alexander the Great.

The Vergina tomb was actually comprised of two tombs. Tomb I, which held human remains but had been looted in antiquity; and Tomb II, which was filled with treasure and armor, as well as the burnt bones of a man and a woman. Tomb II was identified as the final resting place of Philip II. But that identification is hotly contested. Some archaeologists believe that the bones actually belong to Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother and a short-lived figurehead king. Philip II, they say, may actually rest in the looted Tomb I. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2015 ]

About 450 tombs dating to the 6th century B.C. have been found at a site called Archontiko in the Macedonian part of northern Greece. Archaeologists Pavlos and Anastasia Chrysostomou, of the Greek Ministry of Culture, say they have found scores of warriors buried with armor, swords, shields adorned with gold and silver as well as noble women with gold, silver amber and faience. These give clues to the rich warrior culture was thriving two centuries before Alexander's birth.

See Separate Article: MACEDONIA: HISTORY, PHILLIP II'S TOMBS ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

Tomb in Amphipolis

The Tomb in Amphipolis (also known as the Amphipolis Tomb) is an ancient Macedonian tomb discovered inside the Kasta mound near Amphipolis, Central Macedonia, in northern Greece in 2012 and first entered in August 2014. Some have said it belong to Roxana, the wife of Alexander the Great, or perhaps his son or mother or even Alexander the Great himself. [Source: theamphipolistomb.com]

According to theamphipolistomb.com: “The Tumulus Tomb of Amphipolis lies on the hill of Kasta inside a 500-meter long surrounding wall of marble and limestone. The Marble wall is almost a perfect circle 3 meters high with a cornice of marble from the Aegean Island of Thassos. This great Tomb and the surrounding wall with its special base and unique design is likely the work of the Architect Deinokratis, who lived at the time of Alexander the Great. Deinokratis and was Alexander's chosen Architect and also a very important person in the time of Alexander.

“The Entry of the Tomb is 13 steps down from the surrounding Wall. The Entry Arch contains two headless/wingless Sphinxes, amazing works of classic art. In front of the Arch and Sphinx Portal there is a Limestone wall protecting and concealing the entire entry of this vast tomb. The design of the Entry and surrounding wall are unique to the ancient Greece world.

“Originally on the top of the Tomb there was a great Stone Lion, the Lion of Amphipolis. The Lion it's self is 5.3 meters high and has a stone base that makes a total [with Lion] height of 15.84 meters. The sculpture who carved the two entry Sphinxes is the [same?] person that sculpted the colossal Lion. We usually associate a Lion with a battle, like the battle of Chaeronea or with for some great General. Since there was no battle around the time the Tomb was built, the archaeologists suggest that the person inside the Tomb could also be some great General from Alexander's time.

“The fact that the Tomb is still sealed is very important because it means that it may contain items and information of great historical value and that they are still in place. This vast Tomb, the Lion and the two Sphinxes represent amazing beauty from the ancient world and may be the guardians of the contents to one of greatest Archaeology excavations of our time.”

Five different persons were found: 1) a 60-year-old woman, 2) a 35-year-old man, a 45-year-old man, an infant and a cremated man or women. A great brouhaha was made about the tomb around the time it was discovered in 2012 and opened in 2014 but since the bodies were analyzed information on the tomb has dried up and claims that it was linked to the family of Alexander the Great have largely been discredited.

Ancient Mass Graves Found Near Athens

In 2016, archaeologists announced that had discovered two mass graves near Athens containing the skeletons of 80 men who may have been followers of ancient would-be tyrant Cylon of Athens. Regional archaeological services director Stella Chryssoulaki reported the findings and theory at a meeting of the Central Archaeological Council, the custodians of Greece's ancient heritage. The remains were found in the Falyron Delta necropolis - a large ancient cemetery unearthed during the construction of a national opera house and library between downtown Athens and the port of Piraeus. The cemetery dates from between the 8th and 5th century B.C. , “a period of great unrest for Athenian society, a period where aristocrats, nobles, are battling with each other for power," Chryssoulaki told Reuters.

from the mass grave near Athens

AFP reported: “The skeletons were found lined up, some on their backs and others on their stomachs. A total of 36 had their hands bound with iron. Two small vases discovered amongst the skeletons have allowed archaeologists to date the graves from between 675 and 650 B.C. "a period of great political turmoil in the region", the ministry said.Archaeologists found the teeth of the men to be in good condition, indicating they were young and healthy. This boosts the theory that they could have been followers of Cylon, a nobleman whose failed coup in the 7th century B.C. is detailed in the accounts of ancient historians Herodotus and Thucydides. [Source: AFP, April 15, 2016 \=]

“Cylon, a former Olympic champion, sought to rule Athens as a tyrant. But Athenians opposed the coup attempt and he and his supporters were forced to seek refuge in the Acropolis, the citadel that is today the Greek capital's biggest tourist attraction. The conspirators eventually surrendered after winning guarantees that their lives would be spared. But Megacles, of the powerful Alcmaeonid clan, had the men massacred — an act condemned as sacrilegious by the city authorities. Historians say this dramatic chapter in the story of ancient Athens showed the aristocracy's resistance to the political transformation that would eventually herald in 2,500 years of Athenian democracy.” \=\

On the skeletons, Deborah Kyvrikosaios of Reuters wrote: some lie in a long neat row in the dug-out sandy ground, others are piled on top of each other, arms and legs twisted with their jaws hanging open. “They have been executed, all in the same manner. But they have been buried with respect," Chryssoulaki said. “They are all tied at the hands with handcuffs and most of them are very very young and in a very good state of health when they were executed."

The experts hope DNA testing and research by anthropologists will uncover exactly how the rows of people died. Whatever happened was violent - most had their arms bound above their heads, the wrists tied together. But the orderly way they have been buried suggest these were more than slaves or common criminals. [Source: Deborah Kyvrikosaios, Reuters, August 1, 2016 ~~]

“More than 1,500 bodies lie in the whole cemetery, some infants laid to rest in ceramic pots, other adults burned on funeral pyres or buried in stone coffins. One casket is made from a wooden boat. Unlike Athens' renowned ancient Kerameikos cemetery, the last resting place of many prominent ancient Greeks, these appear to be the inhabitants of regular neighborhoods.” ~~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except mass grave from Archaeology magazine

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024