Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory

ANCIENT GREEK HISTORIANS

Herodotus and Thucydides The word history is based on Greek word for "inquiry," or "knowing by inquiry." Hecataeus of Miletus (550-489 B.C.) wrote early accounts of the myths: "account of what I considered to be true. For the stories of the Greeks are numerous and, in my opinion ridiculous." He also wrote about customs he observed on his travels. Euhemerus (300 B.C.) wrote “Sacred History” based on inscriptions he thought were written by Zeus himself on the island of Panchaea in the Indian Ocean. He said Gods were real people later deified.

One of the major things that distinguished historians from the myth makers that preceded them were the fact that they signed their names on their works, so that we know at least they were the sources. Only the works of three historians — Herodotus (484?-425? B.C.), Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) and Xenophon — survived from the first 500 years of Greek history.

An ancient Greek version of “Who's Who” called “ Tables of Persons Eminent in Every Branch of Learning” was prepared between 280 and 250 B.C. by Callimachus. It contained lists and brief biographies of well known lyric poets, writers, tragedians, comedians, orators, philosophers and doctors. "Under Thucydides the description read: "Thucydides was of Athenian birth, the son of Olorus. Slanderers claim his father was a Thracian who migrated to Athens. A very able writer, he composed a history of war between Athens and Sparta."

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

Links to Works by Plutarch

Lives, trans. John Dryden MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ;

Lives Vol 1, trans. Aubrey Stewart and George Long Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Lives Vol 2, trans. Aubrey Stewart and George Long Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Lives Vol 3, trans. Aubrey Stewart and George Long Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Lives Vol 4, trans. Aubrey Stewart and George Long Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, trans. Arthur H. Clough Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Links to Works by Pausanias

Description of Greece Vol 1 Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Description of Greece Vol 2 Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Description of Greece: Book I: Attica (Athens and Megara) sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Description of Greece: Book II: Corinth sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Portable Greek Historians: The Essence of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius” (Portable Library) by M. I. Finley and M. Finley (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Historians” by T. James J. Luce Amazon.com;

“The Essential Greek Historians” by Stanley Burstein (2022) Amazon.com;

“Readings in the Classical Historians” by Michael Grant Amazon.com;

“Herodotus” by James Romm Amazon.com is a “lively short study.”

“ The Way of Herodotus” by Justin Marozzi (De Capo 2009) Amazon.com is an excellent travelog and encounter with Herodotus.

“The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) Amazon.com is richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts on everything from designs of ships to ancient measurements but the translation leaves much to be desired.

The 1858 translation of “Histories” by George Rawlinson (Everyman Library) Amazon.com captures the “rich Homeric flavor and dense syntax” according to The New Yorker.

The 1998 translation of “Histories” by Robin Waterfield (Oxford World Classic) Amazon.com; is pretty good.

“History of the Peloponnesian War” by Thucydides (1834) Amazon.com;

“Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan, (Viking, 2009); Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale. Amazon.com;

“Hellenica” by Xenophon (Landmark) Amazon.com;

“Anabasis” by Xenophon (1847) Amazon.com;

“Parallel Lives” by Plutarch Volume 1 (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

“Parallel Lives” by Plutarch Volume 2 (Modern Library Classics) Amazon.com;

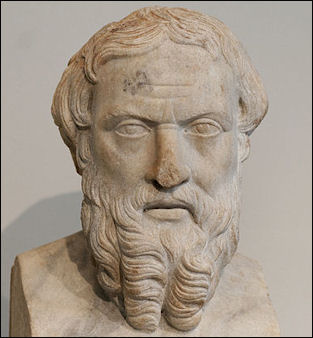

Herodotus

Herodotus (484?-425? B.C.) has been called the Father of History, a compliment initially given to him Cicero. He is given credit for recording information from all over but criticized for using less than reliable sources and sometimes espousing what seems like propaganda. Most of Herodotus's histories were stories he picked up from travelers, merchants and priests. He seems to have known many were exaggerations or unproven claims and he made some effort to pick out what was plausible. Occasionally he ascribed events to myths. Aristotle called him a “legend monger.” [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, April 28, 2008]

Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in The New Yorker, “Herodotus may not always give us the facts, but he unfailingly supplies something that is just as important in the study if what he calls “ta genomena ex anthrupon” or “things that result from human action”: he give us the truth about the way things tend to work as whole, in history, civics, personality, and, of course, psychology.”

Herodotos Matt Bune of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote:: “Herodotus was a Greek historian in the fifth century B.C. His birth was around 490 B.C. References to certain events in his narratives suggest that he did not die until at least 431 B.C.E, which was the beginning of the Peloponesian War. In his later years, Herodotus traveled extensively throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. There, he visited the Black Sea, Babylon, Phoenicia, and Egypt. He is best known for his work entitled Histories. Because of this, Cicero claimed him to be the Father of History. Histories is the story of the rise of Persian power and the friction between Persia and Greece. The battles that are described are the ones fought at Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis. His story is the historical record of events that happened in his own lifetime. The first Persian War took place just before he was born, while the second happened when he was a child. This gave him the opportunity to question his elders about the events in both wars to get the details he wanted for his story. “Although early Egyptologists regarded his chronicles of Egypt as a valuable source of information, the accuracy of some of Herodotus' writings have been challenged. His eyewitness accounts are thought of as accurate, but the stories told to him are questioned. Some researchers think the people who told Herodotus information could have forgotten parts, or just humored him with an interesting answer having nothing to do with the truth." [Source: Matt Bune Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, a town in Asia Minor that was home to one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, which was finished decades after he left. Halicarnassus was also regarded as a major intellectual center for a time. Herodotus spent some time in Athens and was a friend of Sophocles. He traveled widely and wrote extensively about the places he visited and people and places he heard about. He visited Egypt, southern Italy, Mesopotamia, Persian, the Levent and the Black Sea area. He wrote about the Scythians based on things he heard and pieced together the Persian Wars from oral traditions and things he observed. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin,∞]

Book: “Herodotus” by James Romm is a “lively short study.” “The Way of Herodotus” by Justin Marozzi (De Capo 2009) is an excellent travelog and encounter with Herodotus. “The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) is richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts on everything from designs of ships to ancient measurements but the translation leaves much to be desired. The 1858 translation of “Histories” by George Rawlinson (Everyman Library) captures the “rich Homeric flavor and dense syntax” according to The New Yorker. The 1998 translation of Robin Waterfield (Oxford World Classic) is not bad.

See Separate Article: HERODOTUS: HIS LIFE, TRAVELS AND HISTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com

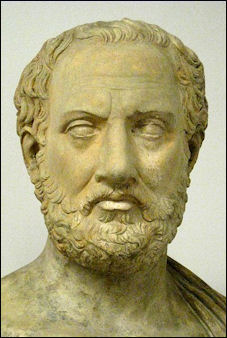

Thucydides

Thucydides Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in “History of the Peloponnesian War”. Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Tracy Lee Simmons wrote in the Washington Post: “One of the most eminently, and now, predictably, quotable figures of the classical world, Thucydides assuredly deserves his press. Few so well understood the machinations of he human heart and mind when facing the extremities of the human predicament — plague, betrayal, defeat, and the abject humiliation of war — and fewer still could distill the hard-won wisdom of experience into tight, shimmering phrases and radiant lapidary passages.”

Thucydides was a participant in the events he described. He caught the plague he detailed with such precision. He was also far from a distant observer of the Peloponnesian War: he was a general high in the Athenian command early in the war who was forced into exile after he failed to prevent the Spartans from capturing the northern city of Amphipolis in 422. He wrote his account years later in part to defend his actions and in the end puts the blame on the demise of Athens on democracy and its demagogue politicians while arguing it was enlightened military that almost saved the day.

Book: “Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan (Viking, 2009). Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale.

See Separate Article: THUCYDIDES: HIS LIFE, OBSERVATIONS, THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR europe.factsanddetails.com

Xenophon

Xenophon, an Athenian born 431 B.C., was a pupil of Socrates who marched with the Spartans, and was exiled from Athens. He was a great admirer of the Spartans. Sparta gave him land and property in Scillus, where he lived for many years before having to move on and settling in Corinth. He died in 354 B.C.

Xenophon

Xenophon's book Anabasis is his record of the entire expedition of Cyrus against the Persians and the Greek mercenaries’ journey home. Xenophon Under the pretext of fighting Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Ionia, Cyrus assembled a massive army composed of native Persian soldiers, but also a large number of Greeks, to fight against his brother Artaxerxes, the king of Persian. Cyrus told the Greeks their enemy was the Pisidians, and so the Greeks were unaware that they were pawns in Cyrus plan to battle against King Artaxerxes II the larger army. At Tarsus the Greeks became aware of Cyrus's plans to depose the king, and as a result, refused to continue. However, Clearchus, a Spartan general, convinced the Greeks to continue with the expedition. The army of Cyrus met the army of Artaxerxes II in the Battle of Cunaxa. Despite effective fighting by the Greeks, Cyrus was killed in the battle. Clearchus was invited to a peace conference and was betrayed and executed along with other generals and many captains. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The mercenaries, known as the Ten Thousand, found themselves without leadership far from the sea, deep in hostile territory near the heart of Mesopotamia. They elected new leaders, including Xenophon himself, and fought their way north along the Tigris through hostile Persians and Medes to Trapezus on the coast of the Black Sea. They then made their way westward back to Greece via Chrysopolis. +

1) Historical and biographical works: A ) Anabasis (also: The Persian Expedition or The March Up Country); B) Cyropaedia (also: The Education of Cyrus); C) Hellenica; D) Agesilaus 2) Socratic works and dialogues: A) Memorabilia; B) Oeconomicus; C) Symposium; D) Apology; E) Hiero. 3) Short treatises: A) On Horsemanship; B) The Cavalry General; C) Hunting with Dogs; D) Ways and Means; and E) Constitution of Sparta.

Links to Works by Xenophon

Anabasis, or March Up Country or Persia Expedition, full text sourcebooks.fordham.edu;

Anabasis Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Anabasis first four books Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Anabasis Vol I on Ancient Greek Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Cyropedia Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Hellenica Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

The Polity of the Athenians and the Lacedaemonians Project Gutenberg Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org;

Callisthenes

Callisthenes of Olynthus (360– 327 B.C.) was a Greek historian in Macedon with connections to both Aristotle and Alexander the Great. He accompanied Alexander the Great during his Asiatic expedition and served as his historian and publicist. He later opposed Alexander’s adoption of Persian culture and was arrested after being implicated in a plot on the king's life; he died in prison. During his life, he authored several works on Greek history and a biography of Alexander the Great. [Source Wikipedia]

During an incident during a royal boar hunt in which Hermolaus of Macedon, one of Alexander’s royal pages and Callisthenes former pupil; Hermolaus broke royal protocol and assisted Alexander in killing the boar. For this Hermolaus was publicly humiliated by flogging as well as the removing of his horse. This led Hermolaus and several other royal pages to create a conspiracy to assassinate Alexander. Yet, the conspiracy was discovered, and the young nobles faced arrest, torture and interrogation.

While under torture, Hermolaus implicated Callisthenes as a part of the plot against Alexander. Because of Callisthenes’ previous opposition to Alexander, as well as his previous role as Hermolaus’s instructor; Alexander found Callisthenes guilty of treason and ordered his subsequent arrest. Callisthenes was subsequently thrown into prison where he died seven months later. There are several different accounts of how he died or was executed. Crucifixion is the method suggested by Ptolemy, but Chares of Mytilene and Aristobulus of Cassandreia both claim that Callisthenes died of natural causes while in prison.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024