Home | Category: Economics and Agriculture

MONEY IN ANCIENT ROME

The sesterce was the currency of Rome." The annual salary of a soldier was around, 1,200 sesterces. At the time of Christ, a bottle of wine sold for about 1 sesterce. Coins from the Roman Empire could have stayed in circulation for a long time, because the silver they contained always remained valuable

Denarii (singular denarius) were silver alloy coins. Aurei were gold pieces. The word denarius was shortened to dinars, the name of the currency still use in several Northern African and Middle east countries including Tunisia and Jordan. Denarii were the standard coin of ancient Rome, and their name survives today in the word for "money" in several Latin-based languages, such as "denaro" in Italian and "dinero" in Spanish.

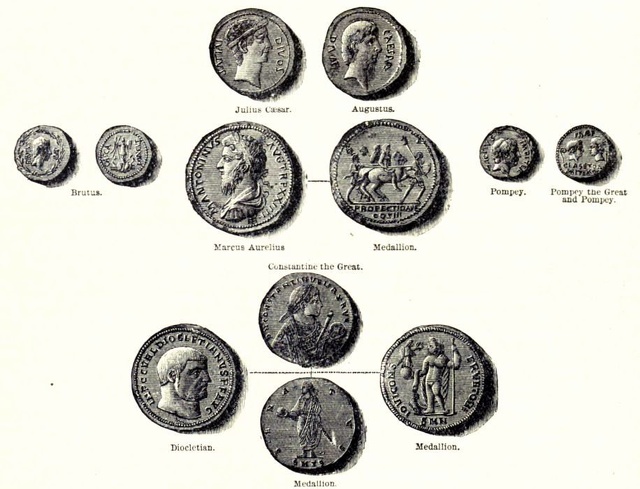

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In the ancient world, coins were minted by hand and, as such, every coin was unique. This made the practical task of identifying counterfeit money that much more difficult. As a result people had to examine their coins and decipher their imagery. This made coins a key means by which propaganda was disseminated, key events were valorized, and leaders touted. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 7, 2018]

The third-century Roman emperor Diocletian proposed a single Europe currency but the idea didn't catch one. Charlemagne's son, Pépin the Short, created a single currency but it didn't last for long.

In 2023, a scuba diver discovered at least 30,000 astonishingly well-preserved Roman coins off Italian coast. Live Science reported: A diver exploring the waters off Sardinia in Italy has discovered tens of thousands of Roman-era bronze coins hidden in the seagrass. The man immediately contacted the authorities about the finding, which was near the town of Arzachena. Based on the location of the hoard, experts think the cache could be connected to an undiscovered shipwreck, according to a translated statement by Italy's Ministry of Culture. Initial weight estimates put the hoard at between 30,000 and 50,000 pieces. Only four were damaged, but even these contained legible inscriptions, including dates and faces. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki. Live Science, November 13, 2023]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ECONOMY OF ANCIENT ROME: GRAIN, SUBSIDIES, INFLATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MAJOR ECONOMIC POLICIES OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BUSINESSES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

INDUSTRIES IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

TRADE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

MINING AND RESOURCES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Money in the Late Roman Republic” by David B. Hollander (2007) Amazon.com;

“Money in Imperial Rome: Legal Diversity and Systemic Complexity” by Merav Haklai (2025) Amazon.com;

“Money in Classical Antiquity” by Sitta von Reden (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Monetary Systems of the Greeks and Romans” by W. V. Harris (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700"

by Kenneth W. Harl (1996) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Ancient Greek and Roman Coins: An Official Whitman Guidebook:by Zander H. Klawans,K. E. Bressett (1995) Amazon.com;

“An Essay on the Ancient Weights and Money and the Roman and Greek Liquid Measures”

by Robert Hussey (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage: From the Reform of Nero to the Reform of Trajan” by Kevin Butcher, Matthew Ponting , et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Soldiers and Silver: Mobilizing Resources in the Age of Roman Conquest” by Michael J. Taylor (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Silver Coins” by Richard Plant (2018) Amazon.com;

“Roman Coins: A Gold Sampler” by Gary Lee Kvamme (2019) Amazon.com;

“Money and Government in the Roman Empire” by Richard Duncan-Jones (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Money and Power in the Roman Republic” by H Beck, M Jehne, et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“An Outline of the Origins of Money” (Classics in Ethnographic Theory)

by Heinrich Schurtz , Enrique Martino, et al. (1898, 2024) Amazon.com;

“Economics, Anthropology and the Origin of Money as a Bargaining Counter’

by Patrick Spread (2022) Amazon.com;

“The History of Money” (1998) by Jack Weatherford Amazon.com;

“Money in Ptolemaic Egypt: From the Macedonian Conquest to the End of the Third Century BC” by Sitta von Reden (2010) Amazon.com;

“Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate” by Claire Holleran (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Retail Revolution: The Socio-Economic World of the Taberna”

by Steven J. R. Ellis (2018) Amazon.com;

“Banking and Business in the Roman World” by Jean Andreau and Janet Lloyd (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy” by Walter Scheidel (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Market Economy” by Peter Temin (2012) Amazon.com;

“Rome's Economic Revolution” by Philip Kay (2014) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Coins and the Rise and Fall of Rome

According to National Geographic: The Romans did not invent the use of currency—the Greek world among others had used it for centuries—but they took it to high art. At first, coins were minted from bronze, but as the Roman Empire expanded, war spoils including silver and gold became the basis of the monetary system. The denominations and values changed over the course of centuries, but certain things remained the same, including the sestertii and denarii persisting as some of history’s most famous coins [Source National Geographic, November 8, 2022].

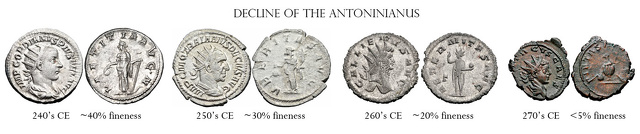

But currency also contributed to Rome’s downfall. In the late second century A.D., Rome experienced a series of economic disasters, including the Antonine plague of A.D. 165, enhanced military spending as Germanic tribes threatened to invade the northern border, and civil wars and social unrest across the empire. Septimius Severus (A.D. 193–211) reduced the amount of silver in each denarius, as imperial powers minted millions of coins to cover expenses. The public confidence in Roman currency waned, igniting inflation. This led to the Imperial Crisis, between A.D. 235 to 284, when more than 20 emperors rose and fell. Inflation sucked the wealth out of 99% of society, leading to mob riots and civil wars. Emperor Diocletian’s solution was to split the empire in two, and the Roman Empire was never the same again.

Archaeologists have unearthed all kinds of different coins that trace this rise and fall.

A gold coin has a relief of a peacock. This gold aureus dates from the imperial era and was made in Rome in the first century A.D. Its relief shows the peacock, the imperial bird.

A silver denarius has two side profiles of men and a serrated edge

A silver denarius features an elephant

A silver coin shows a bust of Venus, with a diadem in her hair and Cupid on her shoulder.

A copper alloy coin shows the two-faced deity Janus

A gold coin features the bust of Constantine

Insights Into History from Roman Coins

Roman coins are an important source of information about things such as dates, political and economic conditions, what Emperors looked like and popular hairstyles at a certain time. Greek coins were not dated, they will not stack, and marks of value are more often absent than present. The earlier Roman coins resembled the Greek in these features, but, later, marks of value were added and the date indicated. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

A Gallic Laelianus Coin — worth about two denarii and dated A.D. 269 — was found Cambridge, England. Made of copper alloy with traces of silver plating and measured about two centimeters (0.8 inches)in diameter, it offers insights to the vagaries of the history at the time it was minted. Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Between A.D. 260 and 274, a succession of generals ruled over the Gallic Empire, a breakaway state from the Roman Empire that included the provinces of Germania, Gaul, Britannia, and, briefly, Hispania. In the spring of A.D. 269, having fended off a Germanic invasion, the military commander Ulpius Cornelius Laelianus declared himself Gallic emperor at Moguntiacum (modern Mainz), the capital of the province of Germania Superior. His reign would not survive the season. [Source:Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

“Save for a mention in the Historia Augusta, a collection of biographies of the Roman emperors written hundreds of years after his reign, Laelianus is largely lost to history. The ill-fated ruler — who appears to have been assassinated by his own troops — is known primarily through the coins he managed to mint despite his brief reign. Thus, the recent discovery of a Laelianus coin during excavations at a small Roman farmstead on the outskirts of Cambridge adds a very short chapter to the enigmatic emperor’s tale. On the front of the coin, Laelianus wears a crown and is surrounded by a phrase identifying him as emperor. The reverse shows a personification of Victory holding a palm frond and wreath meant to proclaim Laelianus’ military prowess. “Many rulers, including Roman emperors, have struck coins to proclaim their position as head of state,” says Julian Bowsher, numismatist at MOLA Headland, which conducted the excavation. “It’s probable that a usurper like Laelianus did so in part to establish his credibility in contrast to his predecessors.”

Although Gallic coins were quite common in Britannia, having been brought over in bulk when the province was part of the Gallic Empire, coins struck by Laelianus are very rare, explains Bowsher. Only about 50 such coins have been found on the island. Equally rare are coins struck by one of Laelianus’ slightly more fortunate successors, a former blacksmith named Marcus Aurelius Marius, who lasted a full three months before he, too, was assassinated.

Debasement of Roman Coinage

J. Wisniewski wrote in Listverse: Beginning with the reign of Nero and continuing for centuries, Roman currency was repeatedly debased as the empire suffered through bouts of inflation, private hoarding, decreased revenue, and skyrocketing military and administrative spending. By the third century A.D., Roman coin was a bad joke whose actual precious metal content was questionable at best. Things got so bad that the Roman government wouldn’t accept tax payments in its own currency. To remedy this and keep paying the troops, crippling taxes were levied on the masses, which made Roman rule increasingly intolerable. Most Western Europeans became convinced they might be better off under barbarian rulers. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “As early as the rule of Nero (54—68 AD.) there is evidence that the demand for revenue led to debasement of the coinage. Revenue was needed to pay the increasing costs of defense and a growing bureaucracy. However, rather than raise taxes, Nero and subsequent emperors preferred to debase the currency by reducing the precious metal content of coins. This was, of course, a form of taxation; in this case, a tax on cash balances. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

“Throughout most of the Empire, the basic units of Roman coinage were the gold aureus, the silver denarius, and the copper or bronze sesterce. 5 The aureus was minted at 40—42 to the pound, the denarius at 84 to the pound, and a sesterce was equivalent to one-quarter of a denarius. Twenty-five denarii equaled one aureus and the denarius was considered the basic coin and unit of account. /=\

Ancient Roman counterfeit coin molds

“The aureus did not circulate widely. Consequently, debasement was mainly limited to the denarius. Nero reduced the silver content of the denarius to 90 percent and slightly reduced the size of the aureus in order to maintain the 25 to 1 ratio. Trajan (98—117 AD.) reduced the silver content to 85 percent, but was able to maintain the ratio because of a large influx of gold. In fact, some historians suggest that he deliberately devalued the denarius precisely in order to maintain the historic ratio. Debasement continued under the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161—180 AD.), who reduced the silver content of the denarius to 75 percent, further reduced by Septimius Severus to 50 percent. By the middle,of the third century A.D., the denarius had a silver content of just 5 percent. /=\

“Interestingly, the continual debasements did not improve the Empire’s fiscal position. This is because of Gresham’s Law (“bad money drives out good”). People would hoard older, high silver content coins and pay their taxes in those with the least silver. Thus the government’s “real” revenues may have actually fallen. As Aurelio Bernardi explains: ‘At the beginning the debasement proved undoubtedly profitable for the state. Nevertheless, in the course of years, this expedient was abused and the century of inflation which had been thus brought about was greatly to the disadvantage of the State’s finances. Prices were rising too rapidly and it became impossible to count on an immediate proportional increase in the fiscal revenue, because of the rigidity of the apparatus of tax collection.’ /=\

Archaeological Evidence of Early Debasement of Roman Coinage

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In his work De Officiis, the first-century B.C. Roman author and orator Cicero alludes to a currency crisis that occurred around 86 B.C. “The coinage was being tossed around,” he writes, “so no one was able to know what he had.” Previous researchers who sampled metal from the surfaces of silver denarius coins from the period found only a slight decline in their purity. Now, a team led by archaeologists Kevin Butcher of the University of Warwick and Matthew Ponting of the University of Liverpool has drilled metal from the cores of coins and found evidence of a brief period of dramatic currency debasement. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022

Until 90 B.C., denarii were pure silver. They were then cut with increasing amounts of copper until the cheaper metal constituted up to 14 percent of the coins’ contents. “Because the Romans had been used to very pure silver coinage, that would have caused a loss of confidence in the value of the denarius,” says Butcher. At the time, Rome was entangled in several wars whose cost apparently led to the currency’s loss of value. “When you get to that level of debasement, you start to see changes to the color of the metal,” says Ponting. “People probably began to notice that things weren’t quite right.” Likely as a reaction to this decline in public confidence, denarii were restored to their former level of purity around 86 B.C.

History of Money in the Early Roman Empire

Reign of Augustus Caesar (30 B.C. - A.D. 14): Augustus reforms the Roman monetary and taxation systems issuing new, almost pure gold and silver coins, and new brass and copper ones, and also introduces three new taxes: a general sales tax, a land tax, and a flat-rate poll tax. [Source: Roy Davies & Glyn Davies, “A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Glyn Davies, rev. ed. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1996 & 1999. Exeter]

Christ drives the money changers out of the Temple in Jerusalem (c. A.D. 30): Jesus overturns the money changers' tables (Matthew 21.12). To gentiles the practice of money changers conducting their business in and around temples and other public buildings would have seemed commonplace. The Greek bankers or trapezitai derived their name from their tables just as the English word bank comes from the Italian banca for bench or counter.

Reign of Nero (A.D. 54- 68): Nero slightly debases the gold and silver coinages, a practice copied by some later emperors, starting mild but prolonged inflation.

A.D. 250: Silver content of Roman coins is down to 40%. After this level is reached inflation accelerates. A.D. 270: Silver content of Roman coins has fallen to only 4%

History of Money in the Mid Roman Empire

Reign of Gallienus (A.D. 260 - 268) During his reign there is a temporary breakdown of the Roman banking system after the banks reject the flakes of copper produced by his mints. [Source: Roy Davies & Glyn Davies, “A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Glyn Davies, rev. ed. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1996 & 1999. Exeter]

Reign of Aurelian (A.D. 270 - 275): Aurelian issues new, nearly pure coins, using gold from his eastern conquests, but raises their nominal value by 2½ times hoping in this way to stay ahead of inflation. However this "reform" sends inflation soaring. A rebellion by mint workers led by Felicissimus costs Aurelian's army some 7,000 casualties.

Reign of Diocletian (A.D. 284 - 305): Diocletian makes vigorous attempts to get to grips with the problem of inflation using a variety of methods but these prove only partially effective at best.

Diocletian reforms the coinage (A.D. 295): This fails to halt inflation, probably because the older coins remain in use and, in accordance with Gresham's law, drive the good coins out of circulation.

Diocletian issues the Edict of Prices (301): The Edict introduces direct controls of prices and also wage rates. This, too, is defeated by market forces.

Diocletian abdicates voluntarily (305): Although his currency reform and prices and incomes policy failed, his other reforms of the Roman administration, including the world's first system of annual budgets, are more successful.

History of Money in the Late Roman Empire

Constantine secures control over the West then the whole Empire (306 - 337): Constantine issues a new gold coin, the Solidus, which continues to be produced in the Eastern Roman Empire unchanged in weight or purity for the next 700 years. [Source: Roy Davies & Glyn Davies, “A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day” by Glyn Davies, rev. ed. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1996 & 1999. Exeter]

Christianity becomes the official faith of the Roman Empire (313): Constantine adopts Christianity and following his conversion, he confiscates the enormous treasures amassed over the centuries in the pagan temples throughout the empire. Consequently, unlike Diocletian, he has easily enough bullion to replace the earlier debased gold coinage. However he continues to produce debased silver and copper coins. Thus the poor, unlike the rich, are left with an inflation-ridden currency.

A.D. 307: One pound of gold is worth 100,000 Denarii. The value of the denarius is only half that stipulated in Diocletian's edict of prices 6 years earlier.

A.D. 324: One pound of gold is worth 300,000 Denarii Later, in Egypt by the middle of the 4th century the denarius' value collapses completely so that a pound of gold is worth 2,120,000,000 denarii: another early example of runaway inflation.

Rome falls to the Visigoths (A.D. 410): Banking is abandoned in western Europe and does not develop again until the time of the Crusades.

Coins cease to be used in Britain as a medium of exchange (A.D. c. 435): As a result of the Anglo-Saxon invasions Britain, uniquely among the former Roman provinces, ceases to use coins as money for nearly 200 years. When they are re-introduced from the Continent they are used initially for ornament.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024