Home | Category: Economics and Agriculture

EARLY ECONOMIC POLICY OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

Aes signatum, produced by the Roman Republic after 450 BC, one of the oldest Roman coins

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “Beginning with the third century B.C. Roman economic policy started to contrast more and more sharply with that in the Hellenistic world, especially Egypt. In Greece and Egypt economic policy had gradually become highly regimented, depriving individuals of the freedom to pursue personal profit in production or trade, crushing them under a heavy burden of oppressive taxation, and forcing workers into vast collectives where they were little better than bees in a great hive. The later Hellenistic period was also one of almost constant warfare, which, together with rampant piracy, closed the seas to trade. The result, predictably, was stagnation. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

“Stagnation bred weakness in the states ofthe Mediterranean, which partially explains the ease with which Rome was able to steadily expand its reach beginning in the 3rd century B.C. By the first century B.C., Rome was the undisputed master of the Mediterranean. However, peace did not follow Rome’s victory, for civil wars sapped its strength.” /=\

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RELATED ARTICLES:

ECONOMY OF ANCIENT ROME: GRAIN, SUBSIDIES, INFLATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MONEY IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, COINS, DEBASEMENT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BUSINESSES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

INDUSTRIES IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

TRADE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

MINING AND RESOURCES IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Origins of the Roman Economy: From the Iron Age to the Early Republic in a Mediterranean Perspective” by Gabriele Cifani (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy” by Walter Scheidel (2012) Amazon.com;

“Rome's Economic Revolution” by Philip Kay (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire: Economy, Society and Culture” by Peter Garnsey, Richard Saller, et al. (2014) Amazon.com;

“Money and Government in the Roman Empire” by Richard Duncan-Jones (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Power and Public Finance at Rome, 264-49 BCE” by James Tan (2017) Amazon.com;

“Taxation in Egypt from Augustus to Diocletian” by Sherman L. Wallace (1938)

Amazon.com;

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Caesar: Politician and Statesman” by Mattias Gelzer, Peter Needham (1968) Amazon.com;

“Augustus: First Emperor of Rome” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2014); Amazon.com;

“The Roman History: The Reign of Augustus” (Penguin Classics) by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“The Age of Augustus”by Werner Eck Amazon.com;

“Augustan Rome” by A Wallace-Hadrill, (Classical World, 1998) Amazon.com;

“Tiberius” by Robin Seager Amazon.com;

“The Successor: Tiberius and the Triumph of the Roman Empire” (2019)

by Willemijn van van Dijk Amazon.com;

“Soldier of Rome: Vespasian's Fury (The Great Jewish Revolt and Year of the Four Emperors)” by James Mace (2014) Amazon.com;

“Vespasian (Roman Imperial Biographies) by Barbara Levick Amazon.com;

“The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine” by Timothy D. Barnes (1982) Amazon.com;

“Diocletian and the Roman Recovery” by Stephen Williams Amazon.com;

Caesar’s Economic Reforms

The next great need of Rome was the improvement of the condition of the lower classes. Caesar well knew that the condition of the people could not be changed in a day; but he believed that the government ought not to encourage pauperism by helping those who ought to help themselves. There were three hundred and twenty thousand persons at Rome to whom grain was distributed. He reduced this number to one hundred and fifty thousand, or more than one half. He provided means of employment for the idle, by constructing new buildings in the city, and other public works; and also by enforcing the law that one third of the labor employed on landed estates should be free labor. As the land of Italy was so completely occupied, he encouraged the establishment, in the provinces, of agricultural colonies which would not only tend to relieve the farmer class, but to Romanize the empire. He relieved the debtor class by a bankrupt law which permitted the insolvent debtor to escape imprisonment by turning over his property to his creditors. In such ways as these, while not pretending to abolish poverty, he afforded better means for the poorer classes to obtain a living. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

His Reform of the Provincial System: The despotism of the Roman republic was nowhere more severe and unjust than in the provinces. This was due to two things—the arbitrary authority of the governor, and the wretched system of farming the taxes. The governor ruled the province, not for the benefit of the provincials, but for the benefit of himself. It is said that the proconsul hoped to make three fortunes out of his province—one to pay his debts, one to bribe the jury if he were brought to trial, and one to keep himself. The tax collector also looked upon the property of the province as a harvest to be divided between the Roman treasury and himself. Caesar put a check upon this system of robbery. The governor was now made a responsible agent of the emperor; and the collection of taxes was placed under a more rigid supervision. The provincials found in Caesar a protector; because his policy involved the welfare of all his subjects. \~\

His Other Reforms and Projects: The most noted of Caesar’s other changes was the reform of the calendar, which has remained as he left it, with slight change, down to the present day. He also intended to codify the Roman law; to provide for the founding of public libraries; to improve the architecture of the city; to drain the Pontine Marshes for the improvement of the public health; to cut a channel through the Isthmus of Corinth; and to extend the empire to its natural limits, the Euphrates, the Danube, and the Rhine. These projects show the comprehensive mind of Caesar. That they would have been carried out in great part, if he had lived, we can scarcely doubt, when we consider his wonderful executive genius and the works he actually accomplished in the short time in which he held his power. \~\

Economic Policies of Augustus

Augustus coin with his nymphomaniac daughter Julia

Suetonius wrote: “He often showed generosity to all classes when occasion offered. For example, by bringing the royal treasures to Rome in his Alexandrian triumph he made ready money so abundant, that the rate of interest fell, and the value of real estate rose greatly; and after that, whenever there was an excess of funds from the property of those who had been condemned, he loaned it without interest for fixed periods to any who could give security for double the amount. He increased the property qualification for Senators, requiring one million two hundred thousand sesterces, instead of eight hundred thousand, and making up the amount for those who did not possess it. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum — Divus Augustus” (“The Lives of the Caesars — The Deified Augustus”), written A.D. c. 110, “Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum,” 2 Vols., trans. J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 123-287]

“He often gave largess [congiarium, strictly a distribution of oil, came to be used of any largess] to the people, but usually of different sums: now four hundred, now three hundred, now two hundred and fifty sesterces a man; and he did not even exclude young boys, though it had been usually for them to receive a share only after the age of eleven. In times of scarcity too he often distributed grain to each man at a very low figure, sometimes for nothing, and he doubled the money tickets [the tesserae nummulariae were small tablets or round hollow balls of wood, marked with numbers; they were distributed to the people instead of money and entitled the holder to receive the sum inscribed upon them — grain, oil, and various commodities were distributed by similar tesserae].

“But to show that he was a prince who desired the public welfare rather than popularity, when the people complained of the scarcity and high price of wine, he sharply rebuked them by saying: "My son-in-law Agrippa has taken good care, by building several aqueducts, that men shall not go thirsty." Again, when the people demanded largess which he had in fact promised, he replied: "I am a man of my word"; but when they called for one which had not been promised, he rebuked them in a proclamation for their shameless impudence, and declared that he would not give it, even though he was intending to do so. With equal dignity and firmness, when he had announced a distribution of money and found that many had been manumitted and added to the list of citizens, he declared that those to whom no promise had been made should receive nothing, and gave the rest less than he had promised, to make the appointed sum suffice. Once indeed in a time of great scarcity when it was difficult to find a remedy, he expelled from the city the slaves that were for sale, as well as the schools of gladiators, all foreigners with the exception of physicians and teachers, and a part of the household slaves; and when grain at last became more plentiful, he writes: "I was strongly inclined to do away forever with distributions of grain, because through dependence on them agriculture was neglected; but I did not carry out my purpose, feeling sure that they would one day be renewed through desire for popular favor." But from that time on he regulated the practice with no less regard for the interests of the farmers and grain-dealers than for those of the populace.

Free-Market Policies under Augustus

Roman market

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “Following the murder of Caesar in 44 B.C., his adopted son Octavian finally brought an end to internal strife with his defeat of Mark Antony in the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Octavian’s victory was due in no small part to his championing of Roman economic freedom against the Oriental despotism of Egypt represented by Antony, who had fled to Egypt and married Cleopatra in 36 B.C. As Oertel (1934: 386) put it, “The victory of Augustus and of the West meant... a repulse of the tendencies towards State capitalism and State socialism which might have come to fruition ... had Antony and Cleopatra been victorious. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

“The long years of war had taken a heavy toll on the Roman economy. Steep taxes and requisitions of supplies by the army, as well as rampant inflation and the closing of trade routes, severely depressed economic growth. Above all, businessmen and traders craved peace and stability inorder to rebuild their wealth. Increasingly, they came to believe that peace and stability could only be maintained if political power were centralized in one man. This man was Octavian, who took the name Augustus and became the first emperor of Rome in 27 B.C., serving until 14 AD. /=\

“Although the establishment of the Roman principate represented a diminution of political freedom, it led to an expansion of economic freedom. In practice, the average Roman had little real political freedom anyway. His power lay not in the ballot box, but in participating in mob activities, although these were often manipulated by unscrupulous leaders for their own benefit. Especially during the Republic, the mob could often make or break Rome’s leaders (Brunt 1966). Of course, economic freedom was not universal. Egypt, which was the personal property of the Roman emperor, largely retained its socialist economic system (Rostovtzeff 1929, Mime 1927). /=\

“Augustus clearly favored private enterprise, private property, and free trade. The burden of taxation was significantly lifted by the abolition of tax farming and the regularization of taxation.Peace brought a revival of trade and commerce, further encouraged by Roman investments in good roads and harbors. Except for modest customs duties (estimated at 5 percent), free trade ruled throughout the Empire. It was, in Michael Rostovtzeff’s words, a period of “almost complete freedom for trade and of splendid opportunities for private initiative”. /=\

“Tiberius, Rome’s second emperor (14—37 AD.), extended the policies of Augustus well into the first century A.D. It was his strong desire to encourage growth and establish a solid middle class (bourgeoisie), which he saw as the backbone of the Empire. Oertel (1939: 232) describes the situation: ‘The first century of our era witnessed a definitely high level of economic prosperity, made possible by exceptionally favorable conditions. Within the framework of the Empire, embracing vast territories in which peace was established and communications were secure, it was possible for a bourgeoisie to come into being whose chief interests were economic, which maintained a form of economy resting on the old city culture and characterized by individualism and private enterprise, and which reaped all the benefits inherent in such a system. The State deliberately encouraged this activity of the bourgeoisie, both directly through government protection and its liberal economic policy, which guaranteed freedom of action and an organic growth on the lines of “laissez faire, laissez aller,” and directly through measures encouraging economic activity.’ /=\

“Of course, economic freedom was not universal. Egypt, which was the personal property of the Roman emperor, largely retained its socialist economic system However, even here some liberalization did occur. Banking was deregulated, leading to the creation of many private banks. Some land was privatized and the state monopolies were weakened, thus giving encouragement to private enterprise even though the economy remained largely nationalized.” /=\

Crackdowns and Austerity Measures of Tiberius

Tiberius coin

Suetonius wrote: “He reduced the cost of the games and shows by cutting down the pay of the actors and limiting the pairs of gladiators to a fixed number. Complaining bitterly that the prices of Corinthian bronzes had risen to an immense figure and that three mullets had been sold for thirty thousand sesterces, he proposed that a limit be set to household furniture and that the prices in the market should be regulated each year at the discretion of the Senate, while the aediles were instructed to put such restrictions on cook-shops and eating-houses as not to allow even pastry to be exposed for sale. Furthermore, to encourage general frugality by his personal example, he often served at formal dinners meats left over from the day before and partly consumed, or the half of a boar, declaring that it had all the qualities of a whole one. He issued an edict forbidding general kissing, as well as the exchange of New Year's gifts after the Kalends of January. It was his custom to return a gift of four-fold value, and in person; but annoyed at being interrupted all through the month by those who did not have access to him on the holiday, he did not continue it. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) Tiberius, “De Vita Caesarum,” written A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920), pp. 291-401]

“He revived the custom of our forefathers, that in the absence of a public prosecutor matrons of ill-repute be punished according to the decision of a council of their relatives. He absolved a Roman knight from his oath and allowed him to put away his wife, who was taken in adultery with her son-in-law, even though he had previously sworn that he would never divorce her. Notorious women had begun to make an open profession of prostitution, to avoid the punishment of the laws by giving up the privileges and rank of matrons, while the most profligate young men of both orders voluntarily incurred degradation from their rank, so as not to be prevented by the decree of the Senate from appearing on the stage and in the arena. All such men and women he punished with exile, to prevent anyone from shielding himself by such a device. He deprived a Senator of his broad stripe on learning that he had moved to his gardens just before the Kalends of July [the first of July was the date for renting and hiring houses and rooms — hence "moving day"], with the design of renting a house in the city at a lower figure after that date. He deposed another from his quaestorship, because he had taken a wife the day before casting lots [to determine his province or sphere of duty] and divorced her the day after.

“He abolished foreign cults, especially the Egyptian and the Jewish rites, compelling all who were addicted to such superstitions to burn their religious vestments and all their paraphernalia. Those of the Jews who were of military age he assigned to provinees of less healthy climate, ostensibly to serve in the army; the others of that same race or of similar beliefs he banished from the city, on pain of slavery for life if they did not obey. He banished the astrologers as well, but pardoned such as begged for indulgence and promised to give up their art.

“He gave special attention to securing safety from prowling brigands and lawless outbreaks, He stationed garrisons of soldiers nearer together than before throughout Italy, while at Rome he established a camp for the barracks of the praetorian cohorts, which before that time had been quartered in isolated groups in divers lodging houses. He took great pains to prevent outbreaks of the populace and punished such as occurred with the utmost severity. When a quarrel in the theatre ended in bloodshed, he banished the leaders of the factions, as well as the actors who were the cause of the dissension; and no entreaties of the people could ever induce him to recall them.

Caligula Pillages and Imposes Huge Taxes to Pay off His Extravagances

coin with Caligula and the three sisters he ravished

Suetonius wrote: “Having thus impoverished himself, from very need he turned his attention to pillage through a complicated and cunningly devised system of false accusations, auction sales, and imposts. He ruled that Roman citizenship could not lawfully be enjoyed by those whose forefathers had obtained it for themselves and their descendants, except in the case of sons, since "descendants" ought not to be understood as going beyond that degree; and when certificates of the deified Julius and Augustus were presented to him, he waved them aside as old and out of date. He also charged that those estates had been falsely returned, to which any addition had later been made from any cause whatever. If any chief centurions since the beginning of Tiberius' reign had not named that emperor or himself among their heirs, he set aside their wills on the ground of ingratitude; also the testaments of all others, as null and void, if anyone said that they had intended to make Caesar their heir when they died. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) “De Vita Caesarum: Caius Caligula” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Caius Caligula”) written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 405-497, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“When he had roused such fear in this way that he came to be named openly as heir by strangers among their intimates and by parents among their children, he accused them of making game of him by continuing to live after such a declaration, and to many of them he sent poisoned dainties. He used further to conduct the trial of such cases in person, naming in advance the sum which he proposed to raise at each sitting, and not rising until it was made up. Impatient of the slightest delay, he once condemned in a single sentence more than forty who were accused on different counts, boasting to Caesonia, when she woke after a nap, of the great amount of business he had done while she was taking her afternoon sleep. Appointing an auction, he put up and sold what was left from all the shows, personally soliciting bids and running them up so high, that some who were forced to buy articles at an enormous price and were thus stripped of their possessions, opened their veins. A well-known incident is that of Aponius Saturninus; he fell asleep on one of the benches, and as the auctioneer was warned by Gaius not to overlook the praetorian gentleman who kept nodding to him, the bidding was not stopped until thirteen gladiators were knocked down to the unconscious sleeper at nine million sesterces.

“When he was in Gaul and had sold at immense figures the jewels, furniture, slaves, and even the freedmen of his sisters who had been condemned to death, finding the business so profitable, he sent to the city for all the paraphernalia of the old palace, seizing for its transportation even public carriages and animals from the bakeries; with the result that bread was often scarce at Rome and many who had cases in court lost them from inability to appear and meet their bail. To get rid of this furniture, he resorted to every kind of trickery and wheedling, now railing at the bidders for avarice and because they were not ashamed to be richer than he, and now feigning regret for allowing common men to acquire the property of princes. Having learned that a rich provincial had paid those who issued the emperor's invitations two hundred thousand sesterces, to be smuggled in among the guests at one of his dinner-parties, he was not in the least displeased that the honor of dining with him was rated so high; but when next day the man appeared at his auction, he sent a messenger to hand him some trifle or other at the price of two hundred thousand sesterces and say that he should dine with Caesar on his personal invitation.

Caligula taxed prostitutes

“He levied new and unheard of taxes, at first through the publicans and then, because their profit was so great, through the centurions and tribunes of the praetorian guard; and there was no class of commodities or men on which he did not impose some form of tariff. On all eatables sold in any part of the city he levied a fixed and definite charge; on lawsuits and legal processes begun anywhere, a fortieth part of the sum involved, providing a penalty in case anyone was found guilty of compromising or abandoning a suit; on the daily wages of porters, an eighth; on the earnings of prostitutes, as much as each received for one embrace; and a clause was added to this chapter of the law, providing that those who had ever been prostitutes or acted as panders should be liable to this public tax, and that even matrimony should not be exempt.

“When taxes of this kind had been proclaimed, but not published in writing, inasmuch as many offences were committed through ignorance of the letter of the law, he at last, on the urgent demand of the people, had the law posted up, but in a very narrow place and in excessively small letters, to prevent the making of a copy. To leave no kind of plunder untried, he opened a brothel in his palace, setting apart a number of rooms and furnishing them to suit the grandeur of the place, where matrons and freeborn youths should stand exposed. Then he sent his pages about the fora and basilicas, to invite young men and old to enjoy themselves, lending money on interest to those who came and having clerks openly take down their names, as contributors to Caesar's revenues. He did not even disdain to make money from play, and to increase his gains by falsehood and even by perjury. Having on one occasion given up his place to the player next him and gone into the courtyard, he spied two wealthy Roman knights passing by; he ordered them to be seized at once and their property confiscated and came back exultant, boasting that he had never played in better luck.

“But when his daughter was born, complaining of his narrow means, and no longer merely of the burdens of a ruler but of those of a father as well, he took up contributions for the girl's maintenance and dowry. He also made proclamation that he would receive New Year's gifts, and on the Kalends of January took his place in the entrance to the Palace, to clutch the coins which a throng of people of all classes showered on him by handfuls and lapfuls. Finally, seized with a mania for feeling the touch of money, he would often pour out huge piles of gold pieces in some open place, walk over them barefooted, and wallow in them for a long time with his whole body.

Vespasian, Money and Control of the Roman Treasury

Suetonius wrote: “The only thing for which he can fairly be censured was his love of money. For not content with reviving the imposts which had been repealed under Galba, he added new and heavy burdens, increasing the amount of tribute paid by the provinces, in some cases actually doubling it, and quite openly carrying on traffic which would be shameful even for a man in private life; for he would buy up certain commodities merely in order to distribute them at a profit. He made no bones of selling offices to candidates and acquittals to men under prosecution, whether innocent or guilty. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum: Vespasian” (“Life of Vespasian”), written c. A.D. 110, translated by J. C. Rolfe, Suetonius, 2 Vols., The Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.281-321]

Vespasian taxed toilets like these in Pompeii

He is even believed to have had the habit of designedly advancing the most rapacious of his procurators to higher posts, that they might he the richer when he later condemned them; in fact, it was common talk that he used these men as sponges, because he, so to speak, soaked them when they were dry and squeezed them when they were wet. Some say that he was naturally covetous and was taunted with it by an old herdsman of his, who on being forced to pay for the freedom for which he earnestly begged Vespasian when he became emperor cried: "The fox changes his fur, but not his nature." Others, on the contrary, believe that he was driven by necessity to raise money by spoliation and robbery because of the desperate state of the treasury and the privy purse; to which he bore witness at the very beginning of his reign by declaring that forty thousand millions were needed to set the State upright. This latter view seems the more probable, since he made the best use of his gains, ill gotten though they were.

“He was most generous to all classes, making up the requisite estate for senators [This had been increased to 1,200,000 sesterces by Augustus], giving needy ex-consuls an annual stipend of five hundred thousand sesterces, restoring to a better condition many cities throughout the empire which had suffered from earthquakes or fires, and in particular encouraging men of talent and the arts.

“He was the first to establish a regular salary of a hundred thousand sesterces for Latin and Greek teachers of rhetoric, paid from the privy purse. He also presented eminent poets with princely largess and great rewards, and artists, too, such as the restorer of the Venus of Cos [Doubtless referring to the statue of Venus consecrated by Vespasian in his Temple of Peace, the sculptor of which, according to Pliny, was unknown. The Venus of Cos was the work of Praxiteles], and of the Colossus [The colossal statue of Nero; see Nero, xxxi.1]. To a mechanical engineer, who promised to transport some heavy columns to the capitol at small expense, he gave no mean reward for his invention, but refused to make use of it, saying: "You must let me feed my poor commons."

“When Titus found fault with him for contriving a tax upon public toilets, he held a piece of money from the first payment to his son's nose, asking whether its odor was offensive to him. When Titus said "No," he replied, "Yet it comes from urine." On the report of a deputation that a colossal statue of great cost had been voted him at public expense, he demanded to have it set up at once, and holding out his open hand, said that the base was ready. He did not cease his jokes even then in apprehension of death and in extreme danger; for when among other portents the Mausoleum [Of Augustus] opened on a sudden and a comet appeared in the heavens, he declared that the former applied to Junia Calvina of the family of Augustus, and the latter to the king of the Parthians, who wore his hair long; and as death drew near, he said: "Woe's me. Methinks I'm turning into a god."”

Trajan Improves Roman Infrastructure with the Spoils of War

Kristin Baird Rattini wrote in National Geographic History: When Dacia finally fell, Trajan took home an astounding bounty, estimated by one contemporary account to be half a million pounds of gold and a million pounds of silver. Trajan put the proceeds from the Dacian War to good use throughout the empire. He built roads, bridges, aqueducts, and harbors from Spain to the Balkans to North Africa. In Rome itself, a new aqueduct supplied the city with water from the north. Trajan’s Column towered over a magnificent new forum, which boasted two libraries, a grand civic space, and a colonnaded plaza. [Source: Kristin Baird Rattini, National Geographic History, June 25, 2019]

Showing tremendous generosity to the Roman people, particularly in areas of social welfare, Trajan increased the amount of grain handed out to poor citizens and doled out cash gifts as well. He allowed provinces to keep gold remittances that would normally be sent to the emperor and reduced taxes. Trajan emulated his friend the historian Pliny the Younger by expanding public funds, called alimenta, to care for poor children. In fact, it was Pliny himself who best captured the sum of Trajan’s reign in one of his many letters to the emperor: “May you then, and the world through your means, enjoy every prosperity worthy of your reign.”

Hadrian, the Master Builder

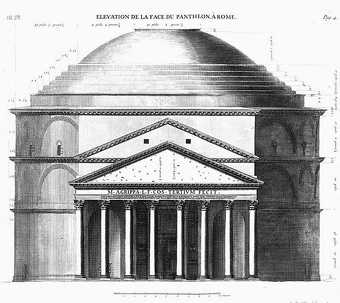

Hadrian was well known for building monuments across the Roman Empire, which was at its largest when he was emperor. Hadrian’s Wall in Britain “and a host of other monuments, attest to his taste, activity, and power.” Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: Hs monuments include "the Pantheon, that Temple of the Divine Trajan, the vast Temple of Venus and Roma, the only building for certain designed by Hadrian, his country estate at Tivoli and, to cap it all, his mausoleum – its ruins now assimilated into Rome’s Castel Sant’ Angelo. His wall in northern England was no exception, either. In the provinces, Hadrian bolstered defences, improved cities and built temples, along the way revolutionising the construction industry and securing jobs and prosperity for the plebs. Hail Hadrian, patron saint of hod-carriers. [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008 ==]

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “In almost every city he built some building and gave public games. At Athens he exhibited in the stadium a hunt of a thousand wild beasts, but he never called away from Rome a single wild-beast-hunter or actor. In Rome, in addition to popular entertainments of unbounded extravagance, he gave spices to the people in honour of his mother-in-law, and in honour of Trajan he caused essences of balsam and saffron to be poured over the seats of the theatre. And in the theatre he presented plays of all kinds in the ancient manner and had the court-players appear before the public. In the Circus he had many wild beasts killed and often a whole hundred of lions. He often gave the people exhibitions of military Pyrrhic dances, and he frequently attended gladiatorial shows. He built public buildings in all places and without number, but he inscribed his own name on none of them except the temple of his father Trajan. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“At Rome he restored the Pantheon, the Voting-enclosure, the Basilica of Neptune, very many temples, the Forum of Augustus, the Baths of Agrippa, and dedicated all of them in the names of their original builders. Also he constructed the bridge named after himself, a tomb on the bank of the Tiber, and the temple of the Bona Dea. With the aid of the architect Decrianus he raised the Colossus and, keeping it in an upright position, moved it away from the place in which the Temple of Rome is now, though its weight was so vast that he had to furnish for the work as many as twenty-four elephants. This statue he then consecrated to the Sun, after removing the features of Nero, to whom it had previously been dedicated, and he also planned, with the assistance of the architect Apollodorus, to make a similar one for the Moon.

Didius Julianus — the Emperor Who Bought the Roman Empire at an Auction

Marcus Didius Julianus served as Roman emperor from March to June 193, during the Year of the Five Emperors. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Didius Julianus served as governor of several provinces and was immensely wealthy. According to the second-century Roman historian Cassius Dio, the Praetorians announced after killing Pertinax that they would sell the throne to the man who paid the highest price, and Julianus won the subsequent bidding war by offering 25,000 sesterces to every Praetorian soldier — the equivalent of several years' pay. After accepting his offer, the Praetorians threatened the Roman senate until they proclaimed Julianus emperor. [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, August 15, 2022]

Didius Julianus

But he didn't enjoy the throne for very long. The Roman people, who knew that he had purchased the emperorship, openly opposed the new emperor, and on one occasion pelted him with stones. Eventually, three different generals in the Roman provinces each declared themselves emperor, and they began advancing on Rome with their armies to enforce their claims. Julianus and the Praetorian Guard fought off one of the generals, Septimius Severus, and tried to negotiate a power-sharing deal with him; but eventually the Praetorians and the senate abandoned Julianus; they proclaimed Severus emperor and ordered Julianus to be executed, just 66 days after he'd ascended the throne.

On how Didius Julianus bought the Roman Empire at auction, Herodian of Syria (3rd Cent. A.D.) wrote in “History of the Emperors”: “When the report of the murder of the Emperor Pertinax spread among the people, consternation and grief seized all minds, and men ran about beside themselves. An undirected effort possessed the people---they strove to hunt out the doers of the deed, yet could neither find nor punish them. But the Senators were the worst disturbed, for it seemed a public calamity that they had lost a kindly father and a righteous ruler. Also a reign of violence was dreaded, for one could guess that the soldiery would find that much to their liking. When the first and the ensuing days had passed, the people dispersed, each man fearing for himself; men of rank, however, fled to their estates outside the city, in order not to risk themselves in the dangers of a change on the throne. But at last when the soldiers were aware that the people were quiet, and that no one would try to avenge the blood of the Emperor, they nevertheless remained inside their barracks and barred the gates; yet they set such of their comrades as had the loudest voices upon the walls, and had them declare that the Empire was for sale at auction, and promise to him who bid highest that they would give him the power, and set him with the armed hand in the imperial palace. [Source: Herodian of Syria, “History of the Emperors” II.6ff, William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

See Separate Article: SEVERANS (193–235 A.D.): YEAR OF FIVE EMPERORS, SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS, AND MAN WHO BOUGHT THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

Diocletian's Price Controls

Crisis of the Third Century in ancient Rome is when a succession of briefly-reigning military emperors, rebellious generals, and counter-claimants presided over governmental chaos, civil war, general instability and great economic disruption. There was a series of weak emperors, each ruling on average only 2 to 3 years, which ended 50 years later with the Tetrarchy instituted in the reign of Diocletian (r. 284–305).

Bruce Bartlett wrote in the Cato Institute Journal: “By the end of the third century, Rome had clearly reached a crisis. The state could no longer obtain sufficient resources even through compulsion and was forced to rely ever more heavily on debasement of the currency to raise revenue. By the reign of Claudius II Gothicus (268—270 A.D.) the silver content of the denarius was down to just .02 percent. As a consequence, prices skyrocketed. A measure of Egyptian wheat, for example, which sold for seven to eight drachmaes in the second century now cost 120,000 drachmaes. This suggests an inflation of 15,000 percent during the third century. [Source: Bruce Bartlett, “How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome,” Cato Institute Journal 14: 2, Fall 1994, Cato.org /=]

Diocletien coin

“Finally, the very survival of the state was at stake. At this point, the Emperor Diocletian (284—305 A.D.) took action. He attempted to stop the inflation with a far-reaching system of price controls on all services and commodities.’° These controls were justified by Diodetian’s belief that the inflation was due mainly to speculation and hoarding, rather than debasement of the currency. As he stated in the preamble to his edict of 301 A.D.: ‘For who is so hard and so devoid of human feeling that he cannot, or rather has not perceived, that in the commerce carried on in the markets or involved in the daily life of cities immoderate prices are so widespread that the unbridled passion for gain is lessened neither by abundant supplies nor by fruitful years; so that without a doubt men who are busied in these affairs constantly plan to control the very winds and weather from the movements of the stars, and, evil that they are, they cannot endure the watering of the fertile fields by the rains from above which bring the hope of future harvests, since they reckon it their own loss if abundance comes through the moderation of the weather.’ /=\

“Despite the fact that the death penalty applied to violations of the price controls, they were a total failure. Lactantius (1984: 11), a contemporary of Diocletian’s, tells us that much blood was shed over “small and cheap items” and that goods disappeared from sale. Yet, “the rise in price got much worse.” Finally, “after many had met their deaths, sheer necessity led to the repeal of the law.” /=\

Diocletian: Prices Edict, 301, Preamble: “For who is so hard and so devoid of human feeling that he cannot, or rather has not perceived, that in the commerce carried on in the markets or involved in the daily life of cities immoderate prices are so widespread that the unbridled passion for gain is lessened neither by abundant supplies nor by fruitful years; so that without a doubt men who are busied in these affairs constantly plan to control the very winds and weather from the movements of the stars, and, evil that they are, they cannot endure the watering of the fertile fields by the rains from above which bring the hope of future harvests, since they reckon it their own loss if abundance comes through the moderation of the weather.”

See Separate Article: DIOCLETIAN: SPLIT OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE, PRICE CONTROLS AND THE TETRARCHY europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024