Home | Category: Food and Sex

FOOD GARDENS IN ANCIENT ROME

Roman relief with olive gathering scene Pompeii created an intricate and robust system for the local production of food and wine. Researchers have long been aware of frescoes, found in many surviving houses and villas, depicting plants and the pleasure of eating and drinking. Remains of triclinia, or dining rooms, and of food stalls, bakeries, and shops selling the fish sauce garum are abundant. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, April/May 2018]

Garden archaeology as a discipline was pioneered in Pompeii in the 1950s when archaeologist Wilhelmina Jashemski began to excavate areas between the remaining structures. She discovered that homeowners planted flowers, dietary staples, and even small vineyards. “From the oldest type of domestic vegetable garden, the hortus, to ornate temple gardens,” explains Betty Jo Mayeske, director of the Pompeii Food and Wine Project, “you see evidence of cultivation in nearly every available space in Pompeii.” It appears that both grain and grapes were grown in small, local contexts.

“There was a bakery on practically every single corner and the mills were there too, as well as a counter room and large ovens,” she says. “The whole production process took place there, and there are also several similar examples of small-scale vineyards.” One of Jashemski’s innovations was to apply the practice of making molds of the dead, known since the 1860s, to making molds of individual plants. “Casting had been done in cement and plaster on human remains for years,” Mayeske says, “but Jashemski used that technology to cast the plants’ roots, which helped definitively identify all of these gardens and vineyards.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

DIET OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EATING HABITS AND CUSTOMS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FOOD IN ANCIENT ROME: STAPLES, EXOTIC DISHES, PIZZA factsanddetails.com

GARUM FISH SAUCE AND SPICES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BREAD IN ANCIENT ROME: GRAINS, MILLING AND PRISON-BAKERIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MEAT AND SEAFOOD IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BANQUETING IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN RESTAURANTS, FOOD STALLS AND FAST FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN RECIPES factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MEAT AND SEAFOOD RECIPES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Rome Olive Guide: Olive Trees, Fruit, Oil & Recipes” by Pliny, Columella, et al. | (2021) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome” by Patrick Faas and Shaun Whiteside (2005) Amazon.com;

“A Taste of Ancient Rome” by Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa, Anna Herklotz (1992) Amazon.com

“The Roman Cookery Book: A Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking, for Use in the Study and the Kitchen” by Elisabeth Rosenbaum (2012) Amazon.com;

“Tasting Rome: Fresh Flavors and Forgotten Recipes from an Ancient City: A Cookbook”

by Katie Parla and Kristina Gill (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Cuisine and Food Culture in Ancient Rome” by Rowan J Trhymden (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Roman World” by Paul Erdkamp and Claire Holleran (2018) Amazon.com;

“Galen on Food and Diet” by Mark Grant (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Cooking: Ingredients, Recipes, Sources” by Marco Gavio de Rubeis (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Cookbook from Ancient Rome: Classic Recipes Reimagined for Today” by Lily Heritage (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Cookbook” by Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger (2012) Amazon.com;

“Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome: An Exploration of Culinary History in an Ancient Roman Cookbook” by Apicius, translated by Joseph Dommers Vehling (2023) Amazon.com;

“In Ancient Rome (Food and Feasts)” by Philip Steele (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“Dining Posture in Ancient Rome: Bodies, Values, and Status” by Matthew B. Roller Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Resilience of the Roman Empire: Regional Case Studies on the Relationship Between Population and Food Resources” by Dimitri Van Limbergen, Sadi Maréchal, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Food Provisions for Ancient Rome: A Supply Chain Approach” by Paul James (2020) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Brill’s Companion to Diet and Logistics in Greek and Roman Warfare (Brill's Companions to Classical Studies: Warfare in the Ancient Mediterranean World”

by John F. Donahue and Lee L. Brice (2023) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

Olives and Olive Oil in the Roman Era

Next in importance to the wheat as a staple food in ancient Rome came the olive. It is estimated that the average Roman consumed 20 liters (more than 5 gallons) of the olive oil each year. In the Roman Empire olive oil was a major cash crop. Consumption by individuals rose to as much as 50 liters a year and some families grew quite rich trading it. In many ways olive oil was valued as much in ancient times as petroleum is today, with governments going to great lengths to make sure there was a steady supply. Some emperors gave it out free to the masses as part of their bread and circuses policy. The main pieces of farm machinery were olive oil presses.

Olives were introduced into Italy from Greece, and from Italy has spread through all the Mediterranean countries; but in ancient times the best olives were those of Italy, even as today the best olives come from Italy. The olive was an important article of food merely as a fruit. It was eaten both fresh and preserved in various ways, but it found its significant place in the domestic economy of the Romans in the form of the olive oil with which we are familiar. It is the value of the oil that has caused the cultivation of the olive to become so general in southern Europe. Many varieties of the olive were known to the Romans; they required different climates and soils and to were adapted to different uses. In general it may be said that the larger fruit were better suited for eating than for oil. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

olive oil storage

The olive was eaten fresh as it ripened and was also preserved in various ways. The ripe olives were sprinkled with salt and left untouched for five days; the salt was then shaken off, and the olives dried in the sun. They were also preserve sweet without salt in boiled must. Half-ripe olives were picked with their stems and covered over in jars with the best quality of oil; in this way they are said to have retained for more than a year the flavor of the fresh fruit. Green olives were preserved whole in strong brine, the form in which we know them now, or were beaten into a mass and preserved with spices and vinegar. The preparation called epityrum was made by taking the fruit in any of the three stages, removing the stones, chopping up the pulp, seasoning it with vinegar, coriander seeds, cumin, fennel, and mint, and covering the mixture in jars with oil enough to exclude the air. The result was a salad that was eaten with cheese. |+|

Olive oil was used for several purposes. It was employed at first to anoint the body after bathing, especially by athletes; it was used as a vehicle for perfumes (the Romans knew nothing of distillation by means of alcohol); it was burned in lamps; it was an indispensable article of food. As a food it was employed in its natural state as butter is now in cooking, or in relishes, or dressings. The olive when subjected to pressure yields two fluids. The first to flow (amurca) is dark and bitter, having the consistency of water. It was largely used as a fertilizer, but not as a food. The second, which flows after greater pressure, is the oil (oleum, oleum olivum). The best oil was made from olives not fully ripe, but the largest quantities was yielded by the ripened fruit.

See Separate Article OLIVES: OIL, HISTORY, PRODUCTION AND SCAMS factsanddetails.com

Olive Oil Trade in the Roman Empire

In Rome, 50-meter (160-foot) -tall Monte Testaccio is an artificial hill made up almost entirely of olive oil amphoras from the ancient Roman province of Baetica in southern Spain.It takes about 20 minutes to walk around it and it’s circumference is almost a mile.Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: As the modern global economy depends on light sweet crude, so too the ancient Romans depended on oil — olive oil. And for more than 250 years, from at least the first century A.D., an enormous number of amphoras filled with olive oil came by ship from the Roman provinces into the city itself. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

In the Roman Empire the Italian peninsula couldn’t produce nearly enough to meet the population’s needs. In addition to being one of the staples of the Mediterranean diet, olive oil was also used for bathing, lighting, medicine, and as a mechanical lubricant. During the emperor Augustus’s reign, olive oil as well as other products, including garum (the fish sauce Romans used to flavor everything from steamed mussels to pear soufflés), metals, and wine began to come into Rome as tax payment in kind from the provinces of Hispania (roughly modern Spain), especially Baetica. Over the next several hundred years, Baetican oil imports continued to grow, reaching their peak at the end of the second century A.D.

Amphorae and the Roman Olive Oil Trade

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: All of this oil came in amphoras. These inexpensive, durable, and often reusable containers (not to be confused with the expensive Greek painted fineware used as prizes in athletic games) were produced all over the empire in distinctive shapes from local materials. More than 85 percent of the amphoras found at Monte Testaccio are the type from Baetica known as Dressel 20, following Dressel’s classification system, which is still in use today. The other 15 percent came from North Africa, chiefly Libya and Tunisia, and are easily distinguished by thinner walls and a more slender shape. Amphoras were also used to transport other products, although the mountains of amphoras for wine or fish products (if they survive) have not been found. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

“The Dressel 20 was perfect for long sea voyages because its globular shape made it less likely to tip over and spill its contents. We can easily imagine ships with cargoes of Dressel 20 amphoras reaching Portus, the Roman port first built beginning in A.D. 42 by the emperor Claudius to replace the old one at Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli). Several shipwrecks, including the Cabrera III wreck found near Mallorca and the Port Vendres II close to Marseille, were found carrying full loads of Baetican exports that included olive oil in Dressel 20s. At Portus, or in the imperial warehouses closer to Monte Testaccio, the oil was emptied into smaller containers for distribution throughout the city. The amphoras were then taken, probably by mule, to Monte Testaccio, where they were discarded. Although many types of amphoras were reused as flower pots and drainpipes, the thick walls and tendency of the Dressel 20s to break into large curved fragments limited their value as recycled products. Much like New York City, which temporarily suspended its plastic bottle recycling program several years ago because of its cost, so too the Romans may have found it cheaper just to throw the amphoras away.

“Oil and amphoras produced in Hispania and transported to Rome for unloading, distribution, and disposal, help tell the story of the Roman economy. Since there is little archaeological evidence of trade in other products such as grain and wine, they also provide a unique snapshot of how Rome developed large-scale imports from the provinces. With such a high volume of imported oil, the Romans needed a system to control distribution and deter cheating and fraud. One of the many advantages of amphoras is that they are easy to write on. Each one carries a thorough accounting of its contents and of the people involved in its creation and transfer. These inscriptions include stamps and incised marks made before firing that refer to the production of the amphora and tituli picti — words, names, and numbers painted on after firing. Both provide a wealth of information about the production, administration, and transport of oil.

“According to Roman pottery expert Theodore Peña of the Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, “One of the keys to comprehending the Roman economy is to understand how the emperor supplied the people of Rome with basic foodstuffs.” This is where Monte Testaccio is again the best source. “In looking at these amphoras,” Peña continues, “we realize that this apparatus for handling oil and possibly grain was unique and went far beyond what the empire did for any other products.”

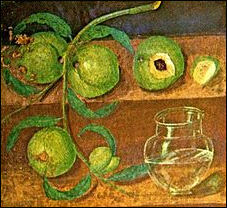

Fruits in the Roman Empire

The Greco-Romans grew and ate tangerines, oranges, lemons, olives, figs, grapes, pears, apples, often in poor soils. Romans grafted apple trees and spread apple cultivation throughout their empire. The apple, pear, plum, and quince were either native to Italy or, like the olive and the grape, were introduced into Italy long before history begins. Careful attention had long been given to their cultivation, and by Cicero’s time Italy was covered with orchards. All these fruits were abundant and cheap in their seasons, and were used by all sorts and conditions of men. By Cicero’s time, too, had begun the introduction of new fruits from foreign lands and the improvement of native varieties. Great statesmen and generals gave their names to new and better sorts of apples and pears, and vied with one another in producing fruits out of season by hothouse culture. Every fresh extension of Roman territory brought new fruits and nuts into Italy. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The Greco-Romans grew and ate tangerines, oranges, lemons, olives, figs, grapes, pears, apples, often in poor soils. Romans grafted apple trees and spread apple cultivation throughout their empire. The apple, pear, plum, and quince were either native to Italy or, like the olive and the grape, were introduced into Italy long before history begins. Careful attention had long been given to their cultivation, and by Cicero’s time Italy was covered with orchards. All these fruits were abundant and cheap in their seasons, and were used by all sorts and conditions of men. By Cicero’s time, too, had begun the introduction of new fruits from foreign lands and the improvement of native varieties. Great statesmen and generals gave their names to new and better sorts of apples and pears, and vied with one another in producing fruits out of season by hothouse culture. Every fresh extension of Roman territory brought new fruits and nuts into Italy. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Lemons, apricots and cherries were introduced to Rome around the A.D. 1st century. The peach (malum Persicum), the apricot (malum Armeniacum), the pomegranate (malum Punicum or granatum), the cherry (cerasus, brought by Lucullus from the town Cerasus in Pontus), and the lemon (citrus, not grown in Italy until the third century of our era). Similarly, the fruits, grains, and vegetables known at home were carried out through the provinces wherever the Romans established themselves. Cherries, for instance, are said to have been grown in Britain in 47 A.D., four years after its conquest. Besides the introduction of fruits for culture, large quantities, either dried or otherwise preserved, were imported for food. The orange, however, strange as this seems to us, was not grown by the Romans. Fresh vegetables, and fresh fruits could not be brought from great distances.” |+|

Pomegranates are ancient fruit. They are mentioned in the Bible, the Koran and the Odyssey. According to one of the most famous Greek myths, Persephone spends six months in the underworld because she ate six pomegranate seeds while held there by Hades. The Assyrians made necklaces of gold pomegranates. Pomegranates are thought have originated in Southeast Asia. They were found in much of the ancient world and are thought to have been introduced to several places by the Phoenicians. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans used the fruit in their medicines.

Figs have been around since ancient times, when they were associated with magic and medicine. The Egyptians buried entire basketfuls with the dead and valued them as a digestive aid. The Greeks called them “the most useful of all the fruits which grow on trees." In the Middle Ages, fig syrup was a popular sweetener.

Apples and Melons in Ancient Rome

strawberries in a Pompeii fresco

Apples were mentioned in the Bible, Greek myths and the Viking sagas. The earliest apples were versions of crab apples. Pictures of apples have been found in caves used by prehistoric men. All trees which produce eating apples are believed to originate from the Malus sieversii tree, which grows in the high altitude forests of Kazakhstan. Almaty, the capital of Kazakhstan, means “father of apples." Apple tree orchards are found in and around Almaty. “Aport” is a famous variety of apple with links to ancient apples. [Source: Natural History, October 2001]

Scientists believe that Malus sieversii was hybridized with crab apples native to Central Asia. Most likely these hybrids, not Malus sieversii itself, became the ancestors of the apples that people eat today. By the 3rd millennium B.C. eating apples were being cultivated over a wide area around the Tien Shan. By the 3rd millennium B.C. eating apples were commonplace around the Mediterranean. The Romans spread apple cultivation throughout their empire.

Melons are one the earliest cultivated crops along with wheat, barley, grapes, and dates. Native to Iran, Turkey and western Asia, they are depicted in an Egyptian tomb painting dated to 2400 B.C. Greek documents from the 3rd century B.C. refer to them. Pliny the Elder described them in the 1st century A.D. in his multi-volume Natural History.

Watermelon originated in Africa. Domesticated watermelon seeds dated to 4000 B.C. were found in the 1980s in southern Libya. Dorian Fuller of the University College London told the New York Times, “The wild watermelon is a horrible, dry little gourd that grows in wadis of the northern savannas, but it has seeds you can roast up and eat." The watermelon we eat was not developed until Roman times.

Spread of Citrus Fruits from Southeast Asia to the Mediterranean

Lemons and citron — the first cirtris fruits- introduced to Rome — were highly valued and only enjoyed by the rich in Ancient Rome: “Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: “Lemons were the acai bowls of the ancient Romans — prized by the privileged because they were rare, and treasured for their healing powers. The upper crust of society likely viewed the citron and the lemon as prized commodities, likely “due to [their] healing qualities, symbolic use, pleasant odor and its rarity,” as well as their culinary qualities, Langgut said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 21, 2017]

Lemons and the citron were the only citrus fruits known in the ancient Mediterranean. Other fruits in the same group, oranges, limes and pomelos, arrived centuries later from their native Southeast Asia, a study led by Dafna Langgut, an archaeobotanist at Tel Aviv University in Israel, revealed. “All other citrus fruits most probably spread more than a millennium later, and for economic reasons,” Langgut, told Live Science. The study was published in the June 2017 issue of the journal HortScience.

Laura Geggel of Live Science wrote: “Studying the ancient citrus trade took a lot of work. Langgut examined ancient texts, art and artifacts, such as murals and coins. She also dug into previous studies to learn about the identities and locations of fossil pollen grains, charcoals, seeds and other fruit remains. “Gathering this information “enabled me to reveal the spread of citrus from Southeast Asia into the Mediterranean,” Langgut said. ~

“The citron (Citrus medica)was the first citrus fruit to reach the Mediterranean, “which is why the whole group of fruits is named after one of its less economically important members,” she said. The citron spread west, likely through Persia (remains of a citron were found in a 2,500-year-old Persian garden near Jerusalem)and the Southern Levant, which today includes Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, southern Syria and Cyprus. Later, during the third and second centuries B.C., it spread to the western Mediterranean, Langgut found. The earliest lemon remains found in Rome were discovered in the Roman Forum, and date to between the late first century B.C. and the early first century A.D., she said. Citron seeds and pollen were also found in gardens owned by the wealthy in the Mount Vesuvius area and Rome, she added. ~

“It took another 400 years for the lemon (Citruslimon) to reach the Mediterranean area. Lemons, too, were owned by the elite class. “This means that for more than a millennium, citron and lemon were the only citrus fruits known in the Mediterranean basin,” Langgut said. The citrus fruits that followed were more likely grown as cash crops, she said. At the beginning of the 10th century A.D., the sour orange (Citrus aurantium), lime (Citrus aurantifolia) and pomelo (Citrus maxima) made it to the Mediterranean. These fruits were likely spread by Muslims through Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula, Langgut said. ~

““The Muslims played a crucial role in the dispersal of cultivated citrus in Northern Africa and Southern Europe, as evident also from the common names of many of the citrus types which were derived from Arabic,” she said. “This was possible because they controlled extensive territory and commerce routes reaching from India to the Mediterranean.” The sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) traveled west even later — during the 15th century A.D. — likely via a trade route established by people from Genoa, Italy; the Portuguese established such a route during the 16th century, Langgut said. Lastly, the mandarin (Citrus reticulata) made it to the Mediterranean in the 19th century, about 2,200 years after the citron first spread west, she said.” ~

Vegetables and Nuts in the Roman Era

.jpg) The Greco-Romans grew and ate cabbage, leeks, onions, chick peas, beans and turnips, often in poor soils. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The garden did not yield to the orchard in the abundance and variety of its contributions to the supply of food. We read of artichokes, asparagus, beans, beets, cabbage, carrots, chicory, cucumbers, garlic, lentils, melons, onions, peas, the poppy, pumpkins, radishes, and turnips, to mention only those whose names are familiar to us all. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

The Greco-Romans grew and ate cabbage, leeks, onions, chick peas, beans and turnips, often in poor soils. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The garden did not yield to the orchard in the abundance and variety of its contributions to the supply of food. We read of artichokes, asparagus, beans, beets, cabbage, carrots, chicory, cucumbers, garlic, lentils, melons, onions, peas, the poppy, pumpkins, radishes, and turnips, to mention only those whose names are familiar to us all. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

It will be noticed, however, that the vegetables perhaps most prized by us, the potato and the tomato, were not known to the Romans. Of those mentioned the oldest seem to have been the bean and the onion, as shown by the names Fabius and Caepio already mentioned, but the latter came gradually to be looked upon as unrefined and the former to be considered too heavy a food except for persons engaged in the hardest toil. Cato pronounced the cabbage the finest vegetable known, and the turnip figures in the well-known anecdote of Manius Curius.

Cucumbers were known in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. They originated in the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India, where they have been cultivated for more than 3,000 years. Asparagus was a favorite of the Romans. It was used mostly as a medicine in the Middle Ages before it became a popular food in the 17th century.

Onions originated in Egypt. Egyptians believed that onions symbolized the many-layered universe. They swore oaths on onions the way oaths are sworn on the Bible in modern times. Radishes were cultivated by the ancient Egyptians at least 4,000 years ago. They were eaten with onions and garlic by laborers. Egyptians believed that radishes were aphrodisiacs, and Ovid wrote of them in the same way. Leeks were also eaten in ancient Egypt. In a popular epigram the poet Martial wrote, "If your wife is old and your member is exhausted, eat onions in plenty."

Among the nuts were the walnut, hazelnut, filbert, almond (after Cato’s time), and the pistachio (not introduced until the time of Tiberius). Almonds are one of the world's oldest cultivated crops. The ancient Mesopotamians used almond oil as a body moisturizer, perfume and hair conditioner. Almonds have been found in the Minoan palace in Knossos and were a favorite dessert food of the Greeks. Almonds and pistachios are the only two nuts mentioned in the Bible.

Cabbages — the "Superfood" of Ancient Rome

Cabbage is the world's most widely consumed vegetable and one of the first to be harvested. Native to the Mediterranean, it was eaten by Achilles in the Iliad and is believed to have been introduced to Europe and other parts of the world by the Romans.

According to History.com: Many Roman doctors linked diet with good health and touted cabbage as a “superfood” that could prevent and treat a wide range of ailments. “It would be a lengthy task to list the good points of the cabbage,” Pliny the Elder wrote. The Roman historian Cato the Elder proved him correct in a nearly 2,000-word treatise on cabbage’s salubrious powers in De Agricultura.

According to Cato, the leafy vegetable cured headaches, vision impairment and digestive issues, while the application of crushed cabbage painlessly healed wounds, contusions, sores and dislocations. “In a word, it will cure all the internal organs which are suffering,” he wrote. Cato even wrote that inhaling the fumes of boiled cabbage promoted fertility and that bathing in the urine of a person who ate a great deal of cabbage cured many ailments.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except garbage, Archaeology News Network

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024