Home | Category: Food and Sex

MEAT IN ANCIENT ROME

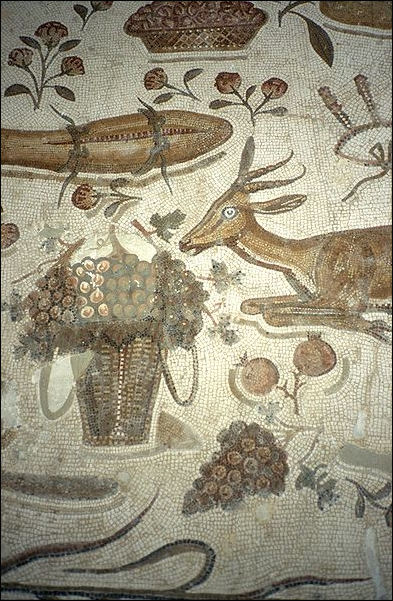

The Romans ate chicken, wild boar, suckling pig, beef, veal, lamb, goat, kid, deer, hare, pheasant, duck, goose, capon (a castrated rooster) and game birds such as thrush, starling and woodcock. They were particularly fond of goose, which was prepared a number of ways with several different sauces. Rabbits are believed to have been domesticated using wild rabbits from Iberia in the Roman Era.

The Romans ate chicken, wild boar, suckling pig, beef, veal, lamb, goat, kid, deer, hare, pheasant, duck, goose, capon (a castrated rooster) and game birds such as thrush, starling and woodcock. They were particularly fond of goose, which was prepared a number of ways with several different sauces. Rabbits are believed to have been domesticated using wild rabbits from Iberia in the Roman Era.

The forests around Roman cities were filled with game. Small birds and mammals were caught in nets. The Romans used dove cotes to raise birds for eggs and meat and produced three-story-high towers to raise dormice, which were a fixture of Roman meals. Cats, rabbits and peacocks were introduced to Rome and eaten by around the A.D. 1st century.

Besides the pork, beef, and mutton that we still use the Roman farmer had goat’s flesh at his disposal; all of these meats were sold in the towns. Goat’s flesh was considered the poorest of all and was used by the lower classes only. Beef had been eaten by the Romans from the earliest times, but its use was a mark of luxury until very late in the Empire. Under the Republic the ordinary citizen ate beef only on great occasions when he had offered a steer or a cow to the gods in sacrifice. The flesh then furnished a banquet for his family and friends; the heart, liver, and lungs (called collectively the exta) were the share of the priest, while certain portions were consumed on the altar. Probably the great size of the carcass had something to do with the rarity of its use at a time when meat could be kept fresh only in the coldest weather; at any rate we must think of the Romans as using cattle for draft and dairy purposes, rather than for food. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Pork was widely used by rich and poor alike, and was considered the choicest of all domestic meats. The very language testifies to the important place the pig occupied in the economy of the larder, for no other animal has so many words to describe it in its different functions. Besides the general term sus we find porcus, porca, verres, aper, scrofa, maialis, and nefrens. In the religious ceremony of the suovetaurilia (sus + ovis + taurus), the swine, it will be noticed, has the first place, coming before the sheep and the bull. The vocabulary describing the parts of the pig used for food is equally rich; there are words for no less than half a dozen kinds of sausages, for example, with pork as their basis. We read, too, of fifty different ways of cooking pork. |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

DIET OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EATING HABITS AND CUSTOMS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com

FOOD IN ANCIENT ROME: STAPLES, EXOTIC DISHES, PIZZA factsanddetails.com

GARUM FISH SAUCE AND SPICES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OLIVES, FRUITS AND VEGETABLES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BREAD IN ANCIENT ROME: GRAINS, MILLING AND PRISON-BAKERIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BANQUETING IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN RESTAURANTS, FOOD STALLS AND FAST FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN RECIPES factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN MEAT AND SEAFOOD RECIPES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Roman Cooking: Ingredients, Recipes, Sources” by Marco Gavio de Rubeis (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Taste of Ancient Rome” by Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa, Anna Herklotz (1992) Amazon.com

“Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome” by Patrick Faas and Shaun Whiteside (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Roman World” by Paul Erdkamp and Claire Holleran (2018) Amazon.com;

“Galen on Food and Diet” by Mark Grant (2002) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Cookery Book: A Critical Translation of the Art of Cooking, for Use in the Study and the Kitchen” by Elisabeth Rosenbaum (2012) Amazon.com;

“Tasting Rome: Fresh Flavors and Forgotten Recipes from an Ancient City: A Cookbook”

by Katie Parla and Kristina Gill (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Cuisine and Food Culture in Ancient Rome” by Rowan J Trhymden (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome Olive Guide: Olive Trees, Fruit, Oil & Recipes” by Pliny, Columella, et al. | (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Cookbook from Ancient Rome: Classic Recipes Reimagined for Today” by Lily Heritage (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Classical Cookbook” by Andrew Dalby and Sally Grainger (2012) Amazon.com;

“Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome: An Exploration of Culinary History in an Ancient Roman Cookbook” by Apicius, translated by Joseph Dommers Vehling (2023) Amazon.com;

“In Ancient Rome (Food and Feasts)” by Philip Steele (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Satyricon” (Penguin Classics) by Petronius (Gaius Petronius Arbiter Amazon.com

“Dining Posture in Ancient Rome: Bodies, Values, and Status” by Matthew B. Roller Amazon.com;

“Food in Roman Britain” by Joan P. Alcock (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Resilience of the Roman Empire: Regional Case Studies on the Relationship Between Population and Food Resources” by Dimitri Van Limbergen, Sadi Maréchal, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

“Food Provisions for Ancient Rome: A Supply Chain Approach” by Paul James (2020) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis”

by Peter Garnsey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Brill’s Companion to Diet and Logistics in Greek and Roman Warfare (Brill's Companions to Classical Studies: Warfare in the Ancient Mediterranean World”

by John F. Donahue and Lee L. Brice (2023) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

Development of the Roman Meat Diet

Joel N. Shurkin wrote in insidescience: “Archaeologists studying the eating habits of ancient Etruscans and Romans have found that pork was the staple of Italian cuisine before and during the Roman Empire. Both the poor and the rich ate pig as the meat of choice, although the rich got better cuts, ate meat more often and likely in larger quantities. They had pork chops and a form of bacon. They even served sausages and prosciutto Angela Trentacoste of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom specializes in the Etruscan civilization that preceded Rome in Italy. Much of her digging was in the tombs of rich Etruscans who often were buried with food and utensils. On some sites, she found 20,000 animal bones amid the rubbish. [Source: Joel N. Shurkin, insidescience, February 3, 2015 +/]

“As the hegemony of Rome grew so did the city and what was a largely rural Etruscan society became a more urban Roman one, she said. That changed the food supply. Most food, as now, came from farms outside the city. But, the city dwellers still raised pigs. They take up little room, can be easily bred and transported, Trentacoste said, and are easy to raise. +/

“They also had chickens roaming the yards that looked much like the chickens of today, MacKinnon said, and they were close to the same size. Modern farmers use breeding and nutrition to make the chickens grow faster, but eventually Roman chickens would catch up. Cattle take up too much room but rich Romans had beef occasionally, and sometimes goat. Low-fat food was not in vogue because the fat would protect meat from spoilage in a world without refrigerators.” +/

fried veal

Roman-Era Butchery in Britain

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: Large amounts of animal bone found in a ditch on the outskirts of a Romano-British settlement near Ipplepen, in southwest England, might point to the operations of a third-century A.D. butchery. Most of the bone came from the feet and heads of cattle likely butchered on-site, which suggests the prime cuts of meat were sold and consumed elsewhere. Burned limestone thrown in with the bone could be evidence of the production of lime, which was often used to process hides to make leather. This, along with butchery marks on some bones that resulted from removing the hides, may indicate that tanners also worked at the site. [Source:Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

“Despite Ipplepen’s location on the western edge of the Roman Empire, explains University of Exeter archaeologist Stephen Rippon, imported tableware and amphoras, which contained olive oil and wine, unearthed at the site reveal that residents adopted at least some Roman dining and culinary practices. However, they continued living in roundhouses similar to those from the settlement’s earliest occupation in the Iron Age, centuries before. Says Rippon, “It was as if they were picking and choosing which aspects of being Roman they liked.”

Chicken and Fowl in Ancient Rome

The common domestic fowls—chickens, ducks, geese, as well as pigeons—were eaten by the Romans, and, besides these, the wealthy raised various sorts of wild fowl for the table, in the game preserves that have been mentioned. Among these were cranes, grouse, partridges, snipe, thrushes, and woodcock. In Cicero’s time the peacock was most highly esteemed, having at the feast much the same place of honor as the turkey has with us; the birds cost as much as ten dollars each. Wild animals also were bred for food in similar preserves; the hare and the wild boar were the favorite. The latter was served whole upon the table, as in feudal times. As a contrast in size the dormouse (glis) may be mentioned; it was thought a great delicacy.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Chickens were raised in Egypt and China for meat and eggs by 1400 B.C. Greeks ate them and they were in Britain at the time the Romans arrived. Some of the earliest evidence of chickens being consumed as food in the West comes from Maresha, an ancient, abandoned city in Israel that flourished in the Hellenistic period from 400 to 200 B.C.. Barely a century later, the Romans starting spreading the chicken-eating habit across their empire. “From this point on, we see chicken everywhere in Europe,” Lee Perry-Gal, a doctoral student in the department of archaeology at the University of Haifa, told NPR“We see a bigger and bigger percent of chicken. It’s like a new cellphone. We see it everywhere.” [Source: Daniel Charles, NPR, July 20, 2015]

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: A group of scholars from the United Kingdom and South Africa have compared the size of chickens over time from Roman Britain to the present day. The results show that chickens gradually increased in size for almost 2,000 years until about 1950, when broiler chickens — those raised to provide meat rather than eggs — started to get huge. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

In ancient times chickens often lived past two years of age — compared to one or two months for modern, industrially-raised chickens, in part because they were regarded as sacred, some scholars have argued. Researchers at the University of Exeter developed a way to examine 3,000-year-old bones that reveal the age at which ancient chickens died. They examined poultry bones from Britain’s Iron Age and Roman and Saxon period and found these chickens lived between two and four years. The researchers believe the chickens they analyzed were used for ritual sacrifices or cockfighting. [Source: Allison Robicelli, Takeout, June 11, 2021]

Professor Naomi Sykes, from the University of Exeter has studied the evolution of domesticated chickens and has argued that chickens were originally raised more for ritual purposes than eating for dinner. According to the New York Times: She was working on some ancient sites in Britain and was surprised by what isotope studies of fossilized chicken bones suggested about the birds’ diet. Isotopes are different forms of elements like carbon and nitrogen, and researchers use the amount of one versus another to determine what animals or humans ate. Different grains or even grains from different geographical regions give different results, or values. “At sites where there’s a lot of chicken sacrifice to the gods of Mercury and Mithras” during the Roman occupation of Britain, Sykes said, “some of the values of those chickens just looked really bizarre.” It seemed the chickens were eating some sort of special diet. She talked to colleagues who told her that, in fact, chickens in Roman times that were to be sacrificed were sometimes fed a special diet of millet in preparation for their ritual slaughter. Eventually, chickens became a major food source. [Source: James Gorman, New York Times, May 12, 2021]

See Separate Article: CHICKENS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS AND DOMESTICATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Archaeologist Find a Still Intact Roman-Era Egg in Britain

In February 2024, archaeologist announced that they had found a still intact Roman-era egg The egg had been discovered in 2010 alongside three others in Aylesbury, England — about 80 kilometers (50 miles) northwest of London — during an excavation led by Edward Biddulph, senior project manager at Oxford Archaeology. “This is the oldest unintentionally preserved avian egg I have ever seen,” Douglas G.D Russell, senior curator of birds’ eggs and nests at the Natural History Museum (NHM), told CNN. He said that there are older eggs with their contents still inside them, like a series of mummified eggs at the NHM probably excavated in Egypt in 1898, but no other known examples of naturally preserved eggs that are this old. [Source: Issy Ronald, CNN, February 13, 2024]

A woven basket, thought to have contained bread, was found alongside the eggs. Pottery and other finds uncovered alongside the egg were dated to the late 3rd century AD, allowing archaeologists to estimate its age. A micro-CT scan of the egg showed it still had liquid inside.

CNN reported: Nestled in a pit that had been used to supply water for malting and brewing until around 270 AD, archaeologists believe that the eggs had been left there as gifts to the gods once the pit had fallen into disuse, Biddulph said.“These sort of areas in the Roman world tend to encourage rituals… as offerings to the gods or good luck, just like people do today throwing coins into fountains,” he added.

Three of the four eggs discovered were whole but, given their extreme fragility, two cracked once they were removed from the wet conditions that had kept them so well preserved, emitting a “sulphurous aroma,” archaeologists said in a press statement at the time. It wasn’t until August 2023 that researchers discovered the liquid inside the one remaining egg when Biddulph said he enlisted conservator Dana Goodburn-Brown, alongside the University of Kent, to conduct a micro-CT scan of the egg, showing that its yolk and white were remarkably still present.

Handling such a fragile and precious discovery has caused Biddulph to sometimes have his “heart in his mouth,” he added. It also left Goodburn-Brown particularly “nervous” when she carried it in a special box on public transport in London to be examined, he added, but the egg has largely remained safe in their offices.

Seafood in Ancient Rome

Romans were very fond of fish sausage. Sausages made by stuffing spiced meat into animal intestines were made by the Babylonians around 1500 B.C. The Greeks also ate such foods. The Romans called them salsus, the source of the word sausage.

Romans ate lobster, crab, octopus, squid, cuttlefish, mullet, sea urchins, scallops, clams, mussels, sea snails, tuna, sea bream, sea bass and scorpion fish. They liked to cook fish live at the table and the Senate once debated the proper way to serve the first turbot. Hadrian was fond of salmon rolled with caviar. Fresh oysters were very popular. They were brought to Rome from Breton in modern-day France by runners in around 24 hours.

The Romans made popular fish soup in huge vats. The upper classes ate peppered fish. The Romans were so fond of fish they badly overfished the Mediterranean. The Romans practiced fish farming and raised eels in tanks. Pliny described one aristocrat who occasionally fed his slaves to the eels.

The rivers of Italy and the surrounding seas must have furnished always a great variety of fish, but in early times fish were not much used as food by the Romans. By the end of the Republic, however, matters had changed, and no article of food brought higher prices than the rarer sorts of fresh fish. Salt fish was exceedingly cheap and was imported in many forms from almost all the Mediterranean harbors. One dish especially, tyrotarichus, made of salt fish, eggs, and cheese, and therefore something like our codfish balls, is mentioned by Cicero in about the same way as we speak of hash. Fresh fish were all the more expensive because they could be transported only while alive. Hence the rich constructed fish ponds on their estates—Lucius Licinius Crassus setting the example in 92 B.C: and both fresh-water and salt-water fish were raised for the table. The names of the favorite sorts mean little to us, but we find the mullet (mullus) and a kind of turbot (rhombus) bringing high prices, while oysters (ostreae) were as popular as they are now.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) ]

Roman Ship Had On-Board Fish Tank

Jo Marchant wrote in Nature.com: “A Roman ship found with a lead pipe piercing its hull has mystified archaeologists. Italian researchers now suggest that the pipe was part of an ingenious pumping system, designed to feed on-board fish tanks with a continuous supply of oxygenated water. Their analysis has been published online in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. Historians have assumed that in ancient times fresh fish were eaten close to where they were caught, because without refrigeration they would have rotted during transportation. But if the latest theory is correct, Roman ships could have carried live fish to buyers across the Mediterranean Sea. [Source: Jo Marchant, Nature.com, May 31, 2011 \=]

“The wrecked ship, which dates from the second century AD, was discovered six miles off the coast of Grado in northeastern Italy, in 1986. It was recovered in pieces in 1999 and is now held in the Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Grado. A small trade ship around 16.5 metres long, the vessel was carrying hundreds of vase-like containers that held processed fish, including sardines and salted mackerel. Carlo Beltrame, a marine archaeologist at the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in Italy, and his colleagues have been trying to make sense of one bizarre feature of the wreck: a lead pipe near the stern that ends in a hole through the hull. The surviving pipe is 1.3 metres long, and 7–10 centimetres in diameter. \=\

“The team concludes that the pipe must have been connected to a piston pump, in which a hand-operated lever moves pistons up and down inside a pair of pipes. One-way valves ensure that water is pushed from one reservoir into another. The Romans had access to such technology, although it hasn’t been seen before on their ships, and the pump itself hasn’t been recovered from the Grado wreck. Archaeologists have previously suggested that a piston pump could have collected bilge water from the bottom of the boat, emptying it through the hole in the hull. But Beltrame points out that chain pumps — in which buckets attached to a looped chain scooped up bilge water and tipped it over the side — were much safer and commonly used for this purpose in ancient times. “No seaman would have drilled a hole in the keel, creating a potential way for water to enter the hull, unless there was a very powerful reason to do so,” he writes. \=\

“Another possible use is to pump sea water into the boat, to wash the decks or fight fires. A similar system was used on Horatio Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But Beltrame and his colleagues argue that the Grado wreck wasn’t big enough to make this worthwhile. They say that the ship’s involvement in the fish trade suggests a very different purpose for the pump — to supply a fish tank.” \=\

Roman Fish Tank Ship Used to Bring Fresh Fish to the Market?

Jo Marchant wrote in Nature.com: ““The researchers calculate that a ship the size of the Grado wreck could have held a tank containing around 4 cubic metres of water. This could have housed 200 kilograms of live fish, such as sea bass or sea bream. To keep the fish alive with a constant oxygen supply, the water in the tank would need to be replaced once every half an hour. The researchers estimate that the piston pump could have supported a flow of 252 litres per minute, allowing the water to be replaced in just 16 minutes. [Source: Jo Marchant, Nature.com, May 31, 2011 \=]

“Tracey Rihll, a historian of ancient Greek and Roman technology at Swansea University, UK, cautions that there is no direct evidence for a fish tank. The researchers “dismiss fire-extinguisher and deck-washing functions too easily in my view”, she says. But although no trace of the tank itself remains, Rihll says the pipe could have been used for such a purpose in the ship’s younger days. Literary and archaeological evidence suggests that live fish were indeed transported by the Greeks and Romans “on a small but significant scale”, she adds. \=\

“The first-century Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote that parrotfish taken from the Black Sea were transported to the Neopolitan coast, where they were introduced into the sea. And the second- and third-century Greek writer Athenaeus described an enormous ship called the Syracousia, which supposedly had a lead-lined saltwater tank to carry fish for use by the cook. However, a fish tank on board a small cargo ship such as the Grado wreck might mean that transport of live fish was a routine part of Roman trade, allowing the rich to feast on fish from remote locations or carrying fish shorter distances from farms to local markets. It would change completely our idea of the fish market in antiquity,” says Beltrame. “We thought that fish must have been eaten near the harbours where the fishing boats arrived. With this system it could be transported everywhere.” \=\

Ancient Mosaics Reveal Changing Fish Size

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in discovery.com: “The dusky grouper, one of the major predators in the Mediterranean sea, used to be so large in antiquity that it was portrayed as a “sea monster,” a new study into ancient depictions of the endangered fish has revealed. “Amazingly, ancient mosaic art has provided important information to reconstruct this fish’s historical baseline,” Paolo Guidetti of the University of Salento in Italy, told Discovery News. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, news.discovery.com, September 13, 2011 -]

“Considered one of the most flavorful species among the Mediterranean fish, the dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus) is a large, long-lived, slow-growing, protogynous hermaphrodite fish (with sex reversal from female to male). It can be found mainly in the Mediterranean, the African west coast and the coast of Brazil. Having faced harvesting for millennia — grouper bones have been found in human settlements dating back more than 100,000 years — this species has been decimated in recent decades by commercial and recreational fishing. It is now categorized as endangered.-

“To look farther back into the grouper’s history, the researchers examined hundreds of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman paintings and mosaics depicting fishing scenes and fish. At the end, they focused on 23 mosaics which represented groupers. In 10 of the 23 mosaics, dating from the 1st to 5th centuries, groupers were portrayed as being very large. Indeed, the ancient Romans might have considered groupers some sort of “sea monsters” able to eat a fisherman whole, as shown in a 2nd century mosaic from the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. -

“To look farther back into the grouper’s history, the researchers examined hundreds of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman paintings and mosaics depicting fishing scenes and fish. At the end, they focused on 23 mosaics which represented groupers. In 10 of the 23 mosaics, dating from the 1st to 5th centuries, groupers were portrayed as being very large. Indeed, the ancient Romans might have considered groupers some sort of “sea monsters” able to eat a fisherman whole, as shown in a 2nd century mosaic from the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. -

“The mosaics also indicated that groupers lived in shallow waters much closer to shore, and were caught by fishermen using poles or harpoons from boats at the water’s surface. It’s a technique that would surely yield no grouper catch today,” said the researchers. Although there are no known instances of dusky groupers attacking human swimmers, the art depictions are very “informative,” said the researchers. These representations suggest that groupers were, in ancient times, so large as to be portrayed as sea monsters and that their habitat use and depth distribution have shifted in historical times,” Guidetti and Micheli wrote. -

“Ancient Roman authors such Ovid (43 B.C. – 18 A.D.) and Pliny the Elder ((23 A.D. – 79 A.D.) reported that groupers were fished by anglers in shallow waters, where they are now rare if not completely absent. According to their accounts, fish were so strong they could break fishing lines. Ancient art provides a link between prehistorical and modern evidence and suggests that shallow near shore Mediterranean ecosystems have lost large, top predators and their corresponding ecological roles,” the researchers concluded.” -

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024