Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

FEATURES OF AN ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSE

During Roman times, when urban areas became crowded and concrete construction was developed, houses with several stories were built for the first time on a large scale. Rural houses were surrounded by sheep pens, small orchards and gardens that varied in size depending on how rich the owner was. Many families kept bees in pottery hives.

According to Listverse: “ Water would be brought in from outside and residents would have to go out to public latrines to use the toilet. Because of the danger of fire, the Romans living in these apartments were not allowed to cook – so they would eat out or buy food in from takeaway shops (called thermopolium).” [Source: Listverse, October 16, 2009]

Our sources of information are unusually abundant. Vitruvius (80–70 to 15 B.C.), the famed military engineer and architect of the time of Caesar and Augustus, has left a work on building, giving in detail his own principles of construction; the works of many of the Roman writers contain either set descriptions of parts of houses or at least numerous hints and allusions that are collectively very helpful; and, finally, the ground plans of many houses have been uncovered in Rome and elsewhere, and in Pompeii we have even the walls of many houses left standing. There are still, however, despite the fullness and authority of our sources, many things in regard to the arrangement and construction of the house that are uncertain and disputed.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) ]

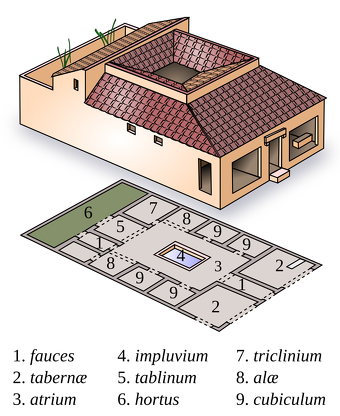

Though the Greek and the Roman house differed considerably in detail, in a general way the two were similar. For Americans the simplest comparison to make would be with the Spanish type of dwelling in California and other parts of the Southwest, since all three have the common characteristic of looking in, rather than out. The exterior presented a blank wall, usually of brick, broken by a door and a few windows. An open courtyard formed the center of the Greek house, and this manner of building was borrowed by the Romans as their wealth increased and larger and pleasanter houses were desired. The Roman house, which grew by the addition of rooms to the original single-room hut, had a large opening in the roof of the principal room or atrium, to provide light and allow the smoke from the hearth to escape. Under the opening was a basin, called impluvium, into which fell the rain-water from the roof. These features were retained even after the atrium was used only as a reception room, the household work and cooking being done in a separate kitchen. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES factsanddetails.com ;

ROOMS AND PARTS OF AN ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSE factsanddetails.com ;

FURNITURE IN ANCIENT ROME: BEDS, COUCHES, TABLES, CHAIRS, FRIDGES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN POSSESSIONS, TOOLS, KITCHEN STUFF, AND PERSONAL OBJECTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN ARCHITECTURE: EMPERORS, ARCHES AND CONCRETE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.- A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration” by by John R. Clarke Amazon.com;

“Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman World” by Alexander Gordon McKay (1975) Amazon.com;

“Style and Function in Roman Decoration: Living with Objects and Interiors”

by Ellen Swift (2018) Amazon.com;

“Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House” by Donatella Mazzoleni , Umberto Pappalardo, et al. (2005) Amazon.com;

“Domestic Space in Classical Antiquity” by Lisa C. Nevett (2010) Amazon.com;

“Water in Ancient Mediterranean Households”by Rick Bonnie (Editor), Patrik Klingborg (2025) Amazon.com;

“Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West: Cultivating Living Buildings” by Ginny Wheeler (2025) Amazon.com;

“Roman Gardens” by Anthony Beeson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula” by Elaine K. Gazda (1991) Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” by Frank Sear (1998) Amazon.com;

“Engineering in the Ancient World” by J. G. Landels (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems”

by Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow (2018) Amazon.com;

“Public Toilets (Foricae) and Sanitation in the Ancient Roman World: Case Studies in Greece and North Africa” by Antonella Patricia Merletto (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner, Thomas Wiedemann Amazon.com;

“The Roman House and Social Identity” by Shelley Hales Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in the Later Roman” by Kim Bowes, Richard Hodges Amazon.com;

“At Home in Roman Egypt: A Social Archaeology” by Anna Lucille Boozer (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Spread of the Roman Domus-Type in Gaul” by Lorinc Timar (2011) Amazon.com;

“Multisensory Living in Ancient Rome: Power and Space in Roman Houses”

by Hannah Platts Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Life in Ancient Rome: People & Places”, 450 Pictures, Maps And Artworks,

by Nigel Rodgers (2014) Amazon.com;

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Walls in a Roman House

The materials of which the walls (parietes) were composed varied with the time, the place, and the cost of transportation. Stone and unburned brick (lateres crudi) were the earliest materials used in Italy, as almost everywhere else, timber being employed for merely temporary structures, as in the addition from which the tablinum, perhaps, developed. For private houses in early times and for public buildings in all times, walls of dressed stone (opus quadratum) were laid in regular courses, precisely as in modern times. As the tufa, the volcanic stone first easily available in Latium, was dull and unattractive in color, over the wall was spread, for decorative purposes, a coating of fine marble stucco which gave it a finish of dazzling white. For less pretentious houses, not for public buildings, sun-dried bricks (the adobe of our southwestern states) were largely used until the beginning of the first century B.C. These, too, were covered with stucco, for protection against the weather as well as for decoration, but even the hard stucco has not preserved walls of this perishable material to our times. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

concrete wall casting

“In classical times a new material had come into use, better than either brick or stone, cheaper, more durable, more easily worked and transported, which was employed almost exclusively for private houses, and very generally for public buildings. Walls constructed in the new way (opus caementicium) are variously called “rubble-work” or “concrete” in our books of reference, but neither term is quite accurate; the opus caementicium was not laid in courses, as is our rubble-work, while on the other hand larger stones were used in it than in the concrete of which walls for buildings are now constructed. |+|

“Paries Caementicius. The materials of the paries caementicius varied with the place. At Rome lime and volcanic ashes (lapis Puteolanus) were used with pieces of stone as large as or larger than the fist. Brickbats sometimes took the place of stone, and sand that of the volcanic ashes; potsherds crushed fine were better than the sand. The harder the stones the better the concrete; the best concrete was made with pieces of lava, the material with which the roads were generally paved. The method of forming the concrete walls was the same as that of modern times. First, upright posts, about 5 by 6 inches thick, and from 10 to 15 feet in height, were fixed about 3 feet apart along the line of both faces of the projected wall. Outside these were nailed, horizontally, boards 10 or 12 inches wide. Into the intermediate space the semi-fluid concrete was poured, receiving the imprint of posts and boards. When the concrete had hardened, the framework was removed and raised; thus the work was continued until the wall had reached the required height. Walls made in this way varied in thickness from a seven-inch partition wall in an ordinary house to the eighteen-foot walls of the Pantheon of Agrippa. They were far more durable than stone walls, which might be removed stone by stone with little more labor than was required to put them together; the concrete wall was a single slab of stone throughout its whole extent, and large parts of it might be cut away without in the slightest degree diminishing the strength of the rest. |+|

“Wall Facings. Impervious to the weather though these walls were, they were usually faced with stone or kiln-burned bricks (lateres cocti). The stone employed was commonly the soft tufa, not nearly so well adapted to stand the weather as the concrete itself. The earliest fashion was to take bits of stone having one smooth face but of no regular size or shape and arrange them, with the smooth faces against the framework, as fast as the concrete was poured in; when the framework was removed, the wall presented the appearance shown at A. Such a wall was called opus incertum. In later times the tufa was used in small blocks having the smooth face square and of a uniform size. A wall so faced looked as if covered with a net and was therefore called opus reticulatum. A corner section is shown at C. In either case the exterior face of the wall was usually covered with a fine limestone or marble stucco, which gave a hard finish, smooth and white. The burned bricks were triangular in shape, but their arrangement and appearance can be more easily understood from the illustration. It must be noticed that there were no walls made of lateres cocti alone; even the thin partition walls had a core of concrete.” |+|

Floors and Ceilings in Roman Houses

In the poorer houses the floor (solum) of the first story was made by smoothing the ground between the walls, covering it thickly with small pieces of stone, bricks, tile, and potsherds, and pounding all down solidly and smoothly with a heavy rammer (fistuca). Such a floor was called pavimentum, but the name came gradually to be used of floors of all kinds. In houses of a better sort the floor was made of stone slabs fitted smoothly together. The more pretentious houses had concrete floors made as has been described. Floors of upper stories were sometimes made of wood, but concrete was used here, too, poured over a temporary flooring of wood. Such a floor was very heavy, and required strong walls to support it; examples are preserved of floors with a thickness of eighteen inches and a span of twenty feet. A floor of this kind made a perfect ceiling for the room below, requiring only a finish of stucco. Other ceilings were made much as they are now: laths were nailed on the stringers or rafters and covered with mortar and stucco.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: ““Floors were also decorated, often with cut marble (opus sectile) or with tessellated mosaics. The mosaics could be quite simple, representing geometric shapes, or very elaborate with complex figural scenes. North Africa and Syria are perhaps the most famous for their mosaics, popularizing hunting scenes in late antiquity. Other themes typified in these mosaics are images of philosophers, rich scenes of animals or the countryside, or scenes of divinities and myth. Many mosaics were a blend of these simple geometric shapes and figural scenes, much like the example in the Museum depicting a garlanded woman surrounded by geometric shapes. [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

recreation of a villa interior in Zaragoza, Spain

“Mosaic decoration was not restricted to the floors of Roman houses. Ceiling and wall mosaics, often of glass, were sometimes employed, used mostly in between columns or in vaulted niches. A well-preserved example can be seen in one of the townhouses at Ephesus in Asia Minor (Turkey). More usual decoration on the ceilings came in the form of molded stucco and painted panels. Stucco panels displayed architectural motifs or molded relief scenes and clad ceilings, especially vaulted ones. The stucco panels in the Museum reflect common thematic concerns of the elite—mythological scenes, exotic animals, and divinities. Such stucco panels could also be used as a decorative element along the tops of walls, similar to the terracotta group in the Museum's collection. The painted panels and stucco decoration were the final part of an interrelated decorative scheme, encompassing the floor, walls, and ceiling. Archaeological remains show that frequently similar colors were used at least on the wall and ceiling panels to create a common aesthetic.” \^/

Roofs on Roman Houses

The roof of a typical house was covered by pottery tiles and designed so it directed water into a storage basin. Roofs were not allowed to be higher than 17 meters (during the reign of Hadrian) due to the danger of collapse, and most apartments had windows.

The construction of the roofs (tecta) differed very little from the modern method. Roofs varied as much as ours do in shape; some were flat, others sloped in two directions, others in four. In the most ancient times the covering was a thatch of straw, as in the so-called hut of Romulus (casa Romuli) on the Palatine Hill, preserved even under the Empire as a relic of the past (see note, page 134). Shingles followed the straw, only to give place, in turn, to tiles. These were at first flat, like our shingles, but were later made with a flange on each side in such a way that the lower part of one would slip into the upper part of the one below it on the roof. The tiles (tegulae) were laid side by side and the flanges covered by other tiles, called imbrices, inverted over them. Gutters also of tile ran along the eaves to conduct the water into cisterns, if it was needed for domestic use.” |+|

Doors in a Roman House

The Roman doorway, like our own, had four parts: the threshold (limen), the two jambs (postes), and the lintel (limen superum). The lintel was always of a single piece of stone and peculiarly massive. The doors were exactly like those of modern times, except in the matter of hinges, for, though the Romans had hinges like ours, they did not use them on their doors. The door-support was really a cylinder of hard wood, a little longer than the door and of a diameter a little greater than the thickness of the door, terminating above and below in pivots. These pivots turned in sockets made to receive them in the threshold and the lintel. To this cylinder the door was mortised, so that the combined weight of cylinder and door came upon the lower pivot. The Roman comedies are full of references to the creaking of the front doors of houses.

“The outer door of the house was properly called ianua, an inner door ostium, but the two words carne to be used indiscriminately, and the latter was even applied to the whole entrance. Double doors were called fores; the back door, opening into a garden or into a peristylium from the rear or from a side street, was called posticum. The doors opened inward; those in the outer wall were supplied with slide-bolts (pessuli) and bars (serae). Locks and keys by which the doors could be fastened from without were not unknown, but were very heavy and clumsy. In the interiors of private houses doors were less common than now, as the Romans preferred portières (vela, aulaea.)

recreation of the interior of a Roman villa in Borg, Germany

Windows in a Roman House

In the principal rooms of a private house the windows (fenestrae) opened on the peristylium, as has been seen, and it may be set down as a rule that in private houses rooms situated on the first floor and used for domestic purposes did not often have windows opening on the street. In the upper floors there were outside windows in such apartments as had no outlook on the peristylium, as in those above the rented rooms in the House of Pansa and in insulae in general. Country houses might have outside windows in the first story. Some windows were provided with shutters, which were made to slide from side to side in a framework on the outside of the wall. These shutters (foriculae, valvae) were sometimes in two parts moving in opposite directions; when closed they were said to be iunctae. Other windows were latticed; others again, were covered with a fine network to keep out mice and other objectionable animals. Glass was known to the Romans of the Empire, but was too expensive for general use in windows. Talc and other translucent materials were also employed in window frames as a protection against cold, but only in very rare instances.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Even in the most luxurious Roman house, the lighting left much to be desired: though the vast bay windows were capable of flooding it at certain hours with the light and air we moderns prize, at other times either both had to be excluded or the inhabitants were blinded and chilled beyond endurance. Neither in the Via Biberatica nor in Trajan's market nor in the Casa dei Dipinti at Ostia do we find any traces of mica or glass near the windows, therefore the windows in these places cannot have been equipped with the fine transparent sheets of lapis specularis with which rich families of the empire sometimes screened the alcove of a bedroom, a bathroom or garden hothouse, or even a sedan chair. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Nor can they have been fitted with the thick, opaque panes which are still found in place in the skylight windows of the baths of Herculaneum and Pompeii, where they provided a hermetic closure to maintain the heat without producing complete darkness. The dwellers in a Roman house must have protected themselves, very inadequately, with hanging cloths or skins blown by wind or drenched by rain; or overwell by folding shutters of one or two leaves which, while keeping cold and rain, midsummer heat or winter wind at bay, also excluded every ray of light. In quarters armed with solid shutters of this sort the occupant, were he an ex-consul or as well known as the Younger Pliny, was condemned either to freeze in daylight or to be sheltered in darkness. The proverb says that a door must be either open or shut. In the Roman insula, on the contrary, the tenant could be comfortable only when the windows were neither completely open nor completely shut; and it is certain that in spite of their size and number, the Romans' windows rendered them neither the service nor the pleasure that ours give us.

Decoration in a Roman House

Houses were small and simple with little decoration until the last century of the Republic. The outside of the house was usually left severely plain; the walls were merely covered with stucco, as we have seen. The interior was decorated to suit the tastes and means of the owner; not even the poorer houses lacked charming effects. At first the stucco-finished walls were merely marked off into rectangular panels (abaci), which were painted in deep, rich colors; reds and yellows predominated. Then in the middle of these panels simple centerpieces were painted, and the whole was surrounded with the most brilliant arabesques. Then came elaborate pictures, figures, interiors, landscapes, etc., of large size and most skillfully executed, all painted directly upon the wall, as in some of our public buildings today. A little later the walls began to be covered with panels of thin slabs of marble with a baseboard and cornice. Beautiful effects were produced by combining marbles of different tints, since the Romans ransacked the world for striking colors. Later still came raised figures of stucco work, enriched with gold and colors, and mosaic work, chiefly of minute pieces of colored glass, which had a jewel-like effect. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The doors and doorways gave opportunities for treatment equally artistic. The doors were richly paneled and carved, or were plated with bronze, or made of solid bronze. The threshold was often of mosaic. The postes were sheathed with marble usually carved in elaborate designs.The floors were covered with marble tiles arranged in geometrical figures with contrasting colors, much as they are now in public buildings, or with mosaic pictures only less beautiful than those upon the walls. The most famous of these, “Darius at the Battle of Issus,” measures sixteen feet by eight, but despite its size has no less than one hundred fifty separate pieces to each square inch. The ceilings were often barrel-vaulted and painted in brilliant colors, or were divided into panels (lacus, lacunae), deeply sunk, by heavy intersecting beams of wood or marble, and then decorated in the most elaborate manner with raised stucco work, or gold or ivory, or with bronze plates heavily gilded.” |+|

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “One of the most well known features of the decoration of a Roman house is wall painting. However, the walls of Roman houses could also be decorated with marble revetment, thin panels of marble of various colors mortared to the wall. This revetment often imitated architecture, by for example being cut to resemble columns and capitals spaced along the wall. Often, even within the same house, plastered walls were painted to appear to be marble revetment, as in the exedral paintings in the collection. The examples at the Museum demonstrate the various possible types of Roman wall painting. An owner might choose to represent ideal landscapes framed by architecture, finer architectural elements and candelabra, or figural scenes relating to entertainment or to mythology, such as the Polyphemus and Galatea scene or the Perseus and Andromeda scene from the villa of Agrippa Posthumus at Boscotrecase. [Source: Ian Lockey, Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The display of statuary of various kinds was an important part of the "furniture" of a Roman house. Sculpture and bronze statues were displayed throughout the house in various contexts—on tables, in specially built niches, in relief panels on walls—but all in the most visible areas of the house. This sculpture could be of numerous types—portrait busts of famous individuals or relatives, lifesize statues of family members, generals, divinities, or mythological figures such as muses. In late antiquity, small-scale sculpture of figures from myth became very popular. In conjunction with the other decorative features of the house, this sculpture was intended to impart a message to visitors. Domestic display is a good example of the conspicuous consumption of the Roman elite, proving that they had wealth and therefore power and authority. Scenes in painting and sculptural collections also helped to associate the owners with key features of Roman life such as education (paideia) and military achievements, validating the owner's position in his world.”“ \^/

Heating in Ancient Rome

Central heating was invented in Roman engineers in the A.D. first century. Seneca wrote it consisted of "tubes embedded in the walls for directing and spreading, equally throughout the house, a soft and regular heat." The tubes were terra cotta and they carried exhaust from a coal or wood fire in the basement. The practice died out in Europe in the Dark Ages.

Even in the mild climate of Italy the houses must often have been too cold for comfort. On merely chilly days the occupants probably contented themselves with moving into rooms warmed by the direct rays of the sun, or with wearing wraps or heavier clothing. In the more severe weather of actual winter they used foculi, charcoal stoves or braziers of the sort still used in the countries of southern Europe. These were merely metal boxes in which hot coals could be put, with legs to keep the floors from injury and handles by which they could be carried from room to room. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

The wealthy sometimes had furnaces resembling ours under their houses; in such cases, the heat was carried to the rooms by tile pipes, The partitions and floors then were generally hollow, and the hot air circulated through them, warming the rooms without being admitted directly to them. These furnaces had chimneys, but furnaces were seldom used in private houses in Italy. Remains of such heating arrangements are found more commonly in the northern provinces, particularly in Britain, where the furnace-heated house seems to have been common in the Roman period.

The heating arrangements in the insula (apartment) were extremely defective. As the atrium had been dispensed with, and the ccnacula were piled one above the other, it was impossible for the inhabitants of an insula to enjoy the luxury common to the peasantry, of gathering round the fire lighted by the womenfolk in the center of their hovels, while sparks and smoke escaped by the gaping hole purposely left in the roof. It would be a grave mistake, moreover, to imagine that the insula ever enjoyed the benefit of central heating with which a misuse of language and an error of fact have credited it. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The furnace arrangements which are found in so many ruins never fulfilled this office. They consisted of, first, a heating apparatus (the hypocausis) consisting of one or two furnaces which were stoked, according to the intensity of heat desired and the length of time it was to be maintained, with wood or charcoal, faggots or dried grass; second, an exit channel through which the heat, the soot, and the smoke penetrated indiscriminately into the adjacent hypocaustum; third, the heat-chamber (the hypocaustum) characterised by piles of bricks in parallel rows, between and over which heat, soot, and smoke circulated together; and finally the heated rooms resting on, or, rather, suspended above the hypocaustum and known, therefore, as the suspensurae.

Whether or not they were connected with it by the spaces within their partition walls, the suspensurae were separated from the hypocaustum by a flooring formed of a bed of bricks, a layer of clay, and a pavement of stone or marble. This compact floor was designed to exclude unwelcome or injurious exhalations and to slow down the rise of temperature. It will be noticed that in this device the heated surface of the suspensurae was never greater than the surface of the hypocaustum and its working demanded a number of hypocauses equal to, if not greater than, the number of hypocausta. It follows, therefore, that this system of furnaces had nothing to do with central heating and was not applicable to many-storied buildings. In ancient Italy it was never used to heat an entire building, unless it was one single and isolated room like the latrine excavated in 1929 at Rome between the Great Forum and the Forum of Caesar. Moreover, even in the buildings where such a furnace system existed, it never occupied more than a small fraction of the house: the bathroom in the best-equipped villas of Pompeii or the caldarium of the public baths. It need hardly be stressed that no traces of such a system have been found in any of the insulae known to us.

Stoves, Fireplaces and Ovens in Ancient Rome

The Romans had no stoves like ours, and rarely did they have any chimneys. The house was warmed by portable furnaces (foculi), like fire pans, in which coal or charcoal was burned, the smoke escaping through the doors or an open place in the roof; sometimes hot air was introduced by pipes from below.” [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

The Roman insula lacked fireplaces as completely as furnaces. Only a few bakeries at Pompeii had an oven supplied with a pipe somewhat resembling our chimney; it would be too much to assume that it was identical with it, for of the two examples that can be cited, one is broken off in such a way that we cannot tell where it used to come out, and the other was not carried up to the roof but into a drying cupboard on the first floor. No such ventilation shafts have been discovered in the villas of Pompeii or Herculaneum; still less, of course, in the houses of Ostia, which reproduce in every detail the plan of the Roman insula. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

pipes

We are driven to conclude that in the houses of the Urbs bread and cakes were cooked with a fire confined in an oven, other food simmered over open stoves, and the inhabitants themselves had no remedy against the cold but what a brazier could provide. Many of these were portable or mounted on runners. Some were wrought in copper or bronze with great taste and skill. But the grace of this industrial art was scant compensation for the brazier's limited heating power and range. The haughtiest dwellings of ancient Rome were strangers alike to the gentle, equal warmth which the radiator spreads through pur rooms and to the cheerfulness of our open fires. They were threatened moreover by the attack of noxious fumes and not infrequently by the escape of smoke which was not always prevented either by the thorough drying or even by the preliminary carbonisation of the fuel (ligna coctilia, acapna).

In February 2023, construction workers unearthed an ancient stove in Genoa that dates back to about the year 300, according to the Genoa government. The furnace resembles a current day stove top. Genoa is on the northwest coast of Italy, about 90 miles south of Milan. [Source: Moira Ritter, Miami Herald , February 22, 2023]

Water Supplies for Roman Housing

In Pompeii, the Vesuvius eruption in A.D. 79 buried the Villa Arianna, which once covered some 27,000 square feet and contained dozens of rooms and lush gardens. While reexcavating in one of the villa’s small peristyles, a team from the Archaeological Superintendency of Pompeii recently uncovered a perfectly preserved, decorated lead water tank and several pipes that had been part of the residence’s state-of-the-art water supply system. The tank would have remained at least partially aboveground to allow access to two shut-off keys used to regulate the flow of water throughout the property. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2023

Things were different for non-rich. The insulae (apartments) of Rome were ill-supplied with water as with light and heat. I admit that the opposite opinion is generally held. People forget that the conveyance of water to the city at State expense was regarded as a purely public service from which private enterprise had been excluded from the first, and which continued to function under the empire for the benefit of the collective population with little regard for the needs of private individuals. According to Frontinus, a contemporary of Trajan, eight aqueducts brought 222,237,060 gallons of water a day to the city of Rome, 68 but very little of this immense supply found its way to private houses. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

In the first place, it was not until the reign of Trajan and the opening on June 24, 109, of the aqueduct called by his name, aqua Traiana, that fresh spring water was brought to the quarters on the right bank of the Tiber; until then, the inhabitants had to make their wells suffice for their needs. Secondly, even on the left bank access to the distributory channels connected by permission of the princeps with the castella of his aqueducts was granted, on payment of a royalty, only to individual concessionaires and to ground landlords;and certainly up to the beginning of the second century these concessions were revocable and were, in fact, brutally revoked by the administration on the very day of the death of a concessionaire. Finally, and most significantly, it seems that these private water supplies were everywhere confined to the ground floor, the chosen residence of the capitalists who had their domus at the base of the apartment blocks.

In the colony of Ostia, for instance, which, like its neighbour Rome, possessed an aqueduct, municipal channels, and private conduits, no building that has so far been excavated reveals any trace of rising columns which might have conveyed spring water to the upper stories. All ancient texts, moreover, whatever the period in which they were written, bear conclusive witness to the absence of any such installations. Under the empire, the poet Martial complains that his town house lacks water although it is situated near an aqueduct. In the Satires of Juvenal the watercarriers (aquarii) are spoken of as the scum of the slave population. The jurists of the first half of the third century considered the water-carriers so vital to the collective life of each insula that they formed, as it were, a part of the building itself and, like the porters (ostiarii) and the sweepers (zetarii), were inherited with the building by the heir or legatees. The praetorian prefect Paulus, in issuing instructions to the praefectus vigilum, did not forget to remind the commandant of the Roman firemen that it was part of his duty to warn tenants always to keep water ready in their rooms to check an outbreak: "ut aquam unusquisque inquilinus in cenaculo habeat iubetur admonere."

Obviously, if the Romans of imperial times had needed only to turn a tap and let floods of water flow into a sink, this warning would have been superfluous. The mere fact that Paulus expressly formulated the warning proves that, with a few exceptions to which we shall revert later, water from the aqueducts reached only the ground floor of the insula. The tenants of the upper cenacula had to go and draw their water from the nearest fountain. The higher the flat was perched, the harder the task of carrying water to scrub the floors and walls of those crowded contignationcs. It must be confessed that the lack of plentiful water for washing invited the tenants of many Roman cenacula to allow filth to accumulate, and it was inevitable that many succumbed to the temptation for lack of a water system such as never existed save in the imagination of too optimistic archaeologists.

Toilets in Ancient Rome

The Romans had flushing toilets. It is well known Romans used underground flowing water to wash away waste but they also had indoor plumbing and fairly advanced toilets. The homes of some rich people had plumbing that brought in hot and cold water and toilets that flushed away waste. Most people however used chamber pots and bedpans or the local neighborhood latrine. [Source: Andrew Handley, Listverse, February 8, 2013]

Toilet in Ephesus Turkey The ancient Romans had pipe heat and employed sanitary technology. Stone receptacles were used for toilets. Romans had heated toilets in their public baths. The ancient Romans and Egyptians had indoor lavatories. There are still the remains of the flushing lavatories that the Roman soldiers used at Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Toilets in Pompeii were called Vespasians after the Roman emperor who charged a toilet tax. During Roman times sewers were developed but few people had access to them. The majority of the people urinated and defecated in clay pots.

Ancient Greek and Roman chamber pots were taken to disposal areas which, according to Greek scholar Ian Jenkins, "was often no further than an open window." Roman public baths had a pubic sanitation system with water piped in and piped out. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse: “Rome has been praised for its advances in plumbing. Their cities had public toilets and full sewage systems, something that later societies wouldn’t share for centuries. That might sound like a tragic loss of an advanced technology, but as it turns out, there was a pretty good reason nobody else used Roman plumbing. “The public toilets were disgusting. Archaeologists believe they were rarely, if ever, cleaned because they have been found to be filled with parasites. In fact, Romans going to the bathroom would carry special combs designed to shave out lice. [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016]

See Separate Article: TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Pompeii House Under Construction Reveals Roman Building Technique

In March 2024, archaeologists excavating a site of Pompeii uncovered building site that was under construction at the time of A.D. 79 Vesuvius eruption, revealing Roman construction techniques used by builders at the time, according to the Italian Ministry of Culture. Barbie Latza Nadeau of CNN wrote: Archaeologists have found what would have been an active construction site — perhaps more accurately described as a home renovation, according to Massimo Osanna, the general director of the site, in a press statement. [Source: Barbie Latza Nadeau, CNN, March 27, 2024]

Scholars said the home being renovated was adjacent to a bakery where slaves and donkeys were locked up together and used to power a mill. The atrium of the house was partially open to the sky and building materials were piled up near a stairwell near the door of the tablinum or reception area that was decorated with a mythological painting of Achilles on Skyros, depicting the ancient Greek hero made famous for his escapades in the Trojan war.

In the latest discovery, archaeologists found evidence of jars, along with tools like lead weights for pulling up heavy walls and iron hoes used to mix the mortar. “Even in the nearby house, reachable from an internal door, and in a large residence behind the two houses, which has so far only been partially investigated, evidence of another large construction site have been found,” the culture ministry said.

The ministry pointed to evidence of enormous piles of stones, ceramics and tiles collected to be transformed into cocciopesto, which was a common floor covering made with plaster and crushed bricks used across the ancient city. Experts previously believed that the quicklime used to plaster walls was pre-mixed with water before it was used, but the recent discoveries instead show how workers mixed it with water on site before using it. The result meant that it was extremely hot to use, but far more effective in giving a long lasting hardened surface, which is in line with recent research that shows that ancient concrete and construction outlasts more recent concrete.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024