Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT ROMAN ARCHITECTURE

Roman structures looked more like modern buildings than their Greek counterparts. Roman structures were not just rows of columns with a roof; the columns intermingled with solid walls and arches. In the introduction of his ten-volume treatise on architecture, the Roman architect Vitruvius laid the basic rules for a good building — it had to be functional, firm and delightful. Thomas Jefferson intended for some of his buildings to resemble a Roman temple, which he described as "one of the most beautiful, if not the most beautiful and precious morsel of architecture left us by antiquity.”

Roman architecture was oriented towards practical purposes and creating interior spaces. Roman buildings looked heavy on the outside. One of the main goals was to create large interior spaces. People are always going on about how uncreative the Roman were." American archaeologist Elizabeth Fentress told National Geographic. "The Romans said it themselves. But it is just simply untrue. They were brilliant engineers. In the Renaissance, when there was this great fever for anything neoclassical, it was Roman not Greek architecture that was copied."

Art and architecture flourished in the Roman Era. In the Roman Republic, the patrons had been private individuals, politicians vying for popular esteem. The Romans made great improvements in their architecture after the Punic Wars (264-146 B.C.). While some public buildings were destroyed by the riots in the city, they were replaced by finer and more durable structures. Many new temples were built—temples to Hercules, to Minerva, to Fortune, to Concord, to Honor and Virtue. There were new basilicas, or halls of justice, the most notable being the Basilica Julia, which was commenced by Julius Caesar. A new forum, the Forum Julii, was also laid out by Caesar, and a new theater was constructed by Pompey. The great national temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, which was burned during the civil war of Marius and Sulla, was restored with great magnificence by Sulla, who adorned it with the columns of the temple of the Olympian Zeus brought from Athens. It was during this period that the triumphal arches were first erected, and became a distinctive feature of Roman architecture. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Eleven miles east of Rome, in the ancient city of Gabii, archaeologists unearthed a building complex that may represent the earliest instance of Roman monumental architecture. This enormous structure, dating to the fourth or third century B.C., was excavated by a team from the University of Michigan and predates most of the grand monuments of Rome itself. The large stone–block construction sprawls across three man-made terraces, enveloping a space of more than 22,000 square feet — roughly an entire ancient city block. The exceptional design features colonnades, geometrically patterned floors, wall paintings, and a grand staircase. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2014]

“Because the site has not yet been fully excavated, it remains to be determined whether this complex served a public or private function. Regardless of the outcome, according to Marcello Mogetta, managing director of the Gabii Project, this structure is unprecedented within the archaeology of the Roman Republic — a period traditionally esteemed for its rejection of opulence and grandeur. If the complex is a private residence, its sheer size makes it unlike any contemporary aristocratic Roman house in Italy, and larger than even those of Pompeii and Rome. “If the interpretation as a public building were confirmed, we would be moving into uncharted territory,” says Mogetta, adding that political buildings of the time were still being built with wooden posts and perishable materials. “The Gabii structure would provide a much earlier example of the desire for monumental architecture in a civic context.”

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: But during the Roman Empire the emperors used art and architecture to advertise their virtues. Augustus claimed that he found Rome brick and left it marble. His two greatest projects, his temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill and his great mausoleum, were planned before the Battle of Actium. Later emperors followed his example, and the cities of the first and second centuries were filled with public buildings in the classical style. Augustus borrowed the models he favored from the Greek Classical Period, and Hadrian, who was a fervent philhellene, sparked a second period of Classicism. Perhaps the most original Roman monument was the Column of Trajan, constructed A.D. 106–113, which presents 150 scenes from Trajan's Dacian War on a continuous scroll wound around the shaft of the column on top of which stood a statue of the emperor himself. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMOUS ANCIENT ROMAN BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BUILDING MATERIALS IN ANCIENT ROME: CONCRETE, BRICKS AND MARBLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROMAN TEMPLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Roman Architecture” by Frank Sear (1998) Amazon.com;

“Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture (Volume 1)” by Vitruvius , Herbert Langford Warren, et al. (1960) Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” (Oxford History of Art) by Janet DeLaine (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Art and Architecture” by Mortimer Wheeler (1971) Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture: A Visual Guide”, Kindle Edition, by Diana E. E. Kleiner (2014) Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” by John Ward-Perkins (1988) Amazon.com;

“City: A Story of Roman Planning and Construction” by David Macaulay (1983) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Roman Architecture” by Mark Wilson Jones Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Roman Architecture” by Roger B. Ulrich, Caroline K. Quenemoen (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Concrete Construction in Roman Architecture: Technology and Society in Republican Italy” by Marcello Mogetta (2021) Amazon.com;

“Building for Eternity: The History and Technology of Roman Concrete Engineering in the Sea” by C.J. Brandon, R.L. Hohlfelder, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman World” by Alexander Gordon McKay (1975) Amazon.com;

“The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.- A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration” by by John R. Clarke Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome” by Diana Buitron-Oliver (1997) Amazon.com;

Roman Construction in Italy from Nerva Through the Antonines” by Marion Elizabeth Blake (1973) Amazon.com;

“Roman Gardens” by Anthony Beeson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Shaping Roman Landscape: Ecocritical Approaches to Architecture and Wall Painting in Early Imperial Italy” by Mantha Zarmakoupi (2023) Amazon.com;

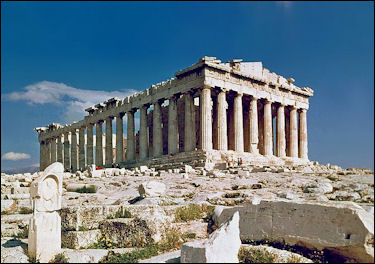

Greek versus Roman Architecture

Parthenon in Athens Some say that the Romans took Etruscan elements — the high podium and columns arranged in a semicircle — and incorporated them with Greek temple architecture. Roman temples were more spacious than their Greek counterparts because unlike the Greeks, who displayed only a statue of the god the temple was built for, the Roman needed room for their statues and weapons they took as trophies from the people they conquered.

One of the main differences between Greek and Roman architecture was that the Greek buildings were intended to be viewed from the outside and Romans created huge indoor spaces that were put to many uses. Greek temples were essentially a roof with forest of columns underneath it that were necessary to support it. They had nevr learned to develop the arch, dome or vaults to great level of sophistication. The Romans used these three elements of architecture to construct all sorts of different kinds of structures: baths, aqueducts, basilicas, etc. The curve was the essential feature: "walls became ceilings, ceilings reached up to the heavens." ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

The Greeks depended on post-and-lintel architecture while the Romans used the arch. The arch helped the Romans construct larger interior spaces. If the Pantheon was built using Greek methods the large open space inside would have been overcrowded with columns.

The historian William C. Morey wrote: “As the Romans were a practical people, their earliest art was shown in their buildings. From the Etruscans they had learned to use the arch and to build strong and massive structures. But the more refined features of art they obtained from the Greeks. While the Romans could never hope to acquire the pure aesthetic spirit of the Greeks, they were inspired with a passion for collecting Greek works of art, and for adorning their buildings with Greek ornaments. They imitated the Greek models and professed to admire the Greek taste; so that they came to be, in fact, the preservers of Greek art. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Vitruvius and De Architectura

Vitruvius(80–70 – after 15 B.C.) was a Roman architect and engineer known for his multi-volume work titled De architectura — the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity. Since the Renaissance it has been regarded as the primary book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture. It is not clear how the work was regarded in its time. [Source Wikipedia]

Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, an illustration of the human body with a circle and a square derived from a passage about geometry and human proportions in Vitruvius' works

Little is known about Vitruvius' life. In his own account he served as an artilleryman, the third class of arms in the Roman military offices. He probably served as a senior officer of artillery in charge of doctores ballistarum (artillery experts) and libratores who actually operated the machines.As an army engineer he specialized in the construction of ballista and scorpio artillery war machines for sieges. It is possible that Vitruvius served with Julius Caesar's chief engineer Lucius Cornelius Balbus.

According to Vitruvius, architecture is an imitation of nature. As birds and bees built their nests, so humans constructed housing from natural materials, that gave them shelter against the elements. When perfecting this art of building, the Greeks invented the architectural orders: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. It gave them a sense of proportion, culminating in understanding the proportions of the greatest work of art: the human body. This led Vitruvius in defining his Vitruvian Man, as drawn later by Leonardo da Vinci: the human body inscribed in the circle and the square (the fundamental geometric patterns of the cosmic order). In this book series, Vitruvius also wrote about climate in relation to housing architecture and how to choose locations for cities.

De Architectura

De architectura, libri decem, known today as The Ten Books on Architecture, is a treatise written in Latin on architecture, dedicated to the emperor Augustus. In it Vitruvius states that all buildings should have three attributes: 1) firmitas, 2) utilitas, and 3) venustas ("strength", "utility", and "beauty"), principles reflected in much Ancient Roman architecture. His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci. Vitruvius' De architectura was well-known and widely copied in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Bramante, Michelangelo, Palladio, Vignola and earlier architects all studied it.

Vitruvius is the first Roman architect to have written surviving records of his field. He himself cites older but less complete works. He was less an original thinker or creative intellect than a codifier of existing architectural practice. Roman architects practised a wide variety of disciplines; in modern terms they would also be described as landscape architects, civil engineers, military engineers, structural engineers, surveyors, artists, and craftsmen combined. Etymologically the word architect derives from Greek words meaning 'master' and 'builder'. The first of the Ten Books deals with many subjects which are now within the scope of landscape architecture.

Vitruvius says that the architect should be versed in drawing, geometry, optics (lighting), history, philosophy, music, theatre, medicine, and law. In Book I, Chapter 3 (The Departments of Architecture), he divides architecture into three branches, namely; building; the construction of sundials and water clocks; and the design and use of machines in construction and warfare. He further divides building into public and private. Public building includes city planning, public security structures such as walls, gates and towers; the convenient placing of public facilities such as theatres, forums and markets, baths, roads and pavings; and the construction and position of shrines and temples for religious use. Later books are devoted to the understanding, design and construction of each of these.

Building Materials in Ancient Rome

Unlike the Greeks who primarily built their edifices from cut and chiseled stone, the Romans used concrete (a mixture of limestone-derived mortar, gravel, sand and rubble) and fired red brick (often decorated with colored glazes) as well as marble and blocks of stone to construct their buildings.

Roman bricks Travertine was used to build the Colosseum and other buildings. It is a kind of yellowish or grayish white limestone formed by mineral springs, especially hot springs, and can form stalactites and stalagmites, but is also a worthy building material as the Colosseum testifies. To the untrained eye ivory-colored travertine can pass as marble. Much of it was mined near Rome in Tivoli.

Many of the buildings that were constructed during the classical period of Rome were made of soft, porous local volcanic rock called tuff that was then faced with marble. The Romans were well aware that tuff was weak especially when soaked with water or soaked with water and subjected to freezing temperatures that occasionally hit Rome. The construction method made sense in that the tuff was cheap, available, close, relatively lightweight and easy to shape. Much of it was extracted in Rome itself and covering it with sheaths marble, which was much easier and cheaper than using heavy, expensive marble blocks.

Vitruvius, the 1st century architect and engineer, wrote: “When it is time to build, the stones should be extracted two years before, not in winter but in summer; then toss them down and leave them in an open place. Whichever of these stones, in two years, is affected or damaged by weather should be thrown in with the foundations. The other ones that are not damaged by means of the trials of nature will be able to endure building above ground.”

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of sedimentary carbonate rock, particularly limestone, that has been recrystalized as a result of extreme pressure and heat within the earth over a long period of time. When polished it gives off a beautiful shine because light rapidly penetrates the surface, giving the stone a luminous, vibrant glow. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Researchers have gained new insight into the efficiency of Roman marble production and decoration strategies employed by Roman architects. Because marble was expensive, Romans often used thin slabs as veneers, attaching them to walls built of less valuable material such as bricks. A recent study led by Cees Passchier, a geologist at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, examined 54 marble panels excavated from a second-century A.D. villa in Ephesus, Turkey. Using 3-D modeling software, Passchier and his team found that 40 of the panels had been precisely cut into 0.6-inch slices from a single block of cipollino verde, a type of greenish marble known for its elaborate wavy folds, using a water-powered sawmill. The researchers determined that the slabs were not randomly hung on the walls. Instead, sections of the block cut one after the other were mounted next to each other in pairs, like opposing pages of a book. The marble’s natural patterns created kaleidoscope-like symmetrical designs. Passchier’s team also determined that the whole process, from cutting to polishing to transportation, was extremely efficient, resulting in only 5 percent of all slabs being broken, a figure on par with present-day marble production. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021

RELATED ARTICLES: BUILDING MATERIALS IN ANCIENT ROME: CONCRETE, BRICKS AND MARBLE europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Arches

arch at the Aquincum Amphitheatre The arch, vault (an arch with depth) and dome are regarded as the most important contributions the Romans made to the world or architecture. The Greeks used the arch, but they found its shape so unappealing they used in mainly sewers.

The Romans perfected the arch and other architectural features developed by the Greeks and created broad porticoes and graceful domes. The dome, an adaption of the arch, was also a Roman innovation. see Pantheon

The Arch of Constantine (between the Colosseum and Palantine Hill) is the largest of ancient Rome's arches. Situated within the same traffic circle that contains the Colosseum, the 66-foot-high arch is one of the best preserved ancient Roman monuments in Rome. Resembling a decorated version of Paris's Arc de Triumph, it was built to honor Constantine's victory over his rival Maxentinus a the Battle of Milvian Bridge in A.D. 315.

The Arch of Titus (on the Colosseum-side entrance of the Forum and Palantine Hill) is a triumphal arch built by Emperor Domitian (ruled A.D. 81-96) to commemorate the victory by his brother Emperor Titus's over the Jews in A.D. 70 and the sacking of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Jewish Temple. On the side of this arch is a frieze, showing Roman soldiers plundering the Temple of Jerusalem and carrying off the Menorah (a sacred candelabra used by Jews during Hanukkah).

Roman Buildings

The forum was the main square or market place of a Roman city. It was the center of Roman social life and the place where business affairs and judicial proceedings were carried out. Here, orators stood on podiums pontificating about the issues of the days, priests offered sacrifices before the gods, chariot-borne emperors rode past worshipping crowds, and crowds milled about shopping, gossiping and simply hanging out.

The most important buildings in the Forum were the “curia” , the high-roofed building where the Senate met, and the “ commitium” , the lower houses where representatives of the plebeians (ordinary people) met.

In Roman times a basilica was a meeting hall or law court. Often attached to the forum, it housed meetings, trials, public meetings, markets and hearings. The word "basilica" comes from the Greek word for "king," so named because of its large size. Other Roman buildings included stoas (shops), civic buildings, bouleteriona (local senate), public libraries, baths and open plazas.

In Rome, the urban poor tended to live in communal housing known as insula. Single-family houses known as domus were primarily for the wealthy and are at least the upper middle class and upwards. These large, comfortable dwellings were often big enough to accommodate the owner’s business, library, kitchen, pool, and garden. The oldest known domus dates to the end of the 4th century B.C. A major structural change was the introduction of the peristyle garden around the 2nd century B.C. Much of what is known about Roman houses comes from the study of dwelling at Pompeii.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES factsanddetails.com ;

ROOMS AND PARTS OF AN ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSE factsanddetails.com ;

FEATURES OF ANCIENT ROMAN HOUSES: WALLS, DOORS, ROOFS, HEATING europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Roman Temples

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important Roman cultural buildings and among the most outstanding examples of Roman architecture, though few exist in complete or near-completer state today. Their construction and activities at them were a major part of ancient Roman religion. All towns of any importance had at least one main temple, as well as smaller shrines. [Source Wikipedia]

Many Roman temples were dedicated to a particularly deity such as Jupiter, Neptune or Venus. The main room (cella) of such temples housed the cult image of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated, and often a table for supplementary offerings or libations and a small altar for incense. Behind the cella was a room, or rooms, used by temple attendants for storage of equipment and offerings. Ordinary worshiper rarely entered the cella, and most public ceremonies were performed outside of the cella at the sacrificial altar on the portico, with a crowd gathered in the temple precinct.

The most common architectural plan for a Roman temple had a rectangular temple raised on a high podium, with a clear front with a portico at the top of steps, and a triangular pediment above columns. The sides and rear of the building had much less architectural emphasis, and typically no entrances. There were also circular plans, generally with columns all round, and outside Italy there were many compromises with traditional local styles. The Roman form of temple developed initially from Etruscan temples, themselves influenced by the Greeks, with subsequent heavy direct influence from Greece.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN TEMPLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Roman Theaters and Amphitheater

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The first permanent theater in the city of Rome was the Theater of Pompey, dedicated in 55 B.C. by Julius Caesar's rival, Pompey the Great. The theater, of which only the foundations are preserved, was an enormous structure, rising to approximately forty-five meters and capable of holding up to 20,000 spectators. At the rear of the stage-building was a large, colonnaded portico, which housed artworks and gardens. Constructed in the wake of Pompey's spectacular military campaigns of the 60s B.C., the theater functioned in large part as a victory monument. The cavea (seating area) was crowned by a temple to Venus Victrix, Pompey's patron deity, and the theater was decorated with statues of the goddess Victory and personifications of the nations that Pompey had subdued in battle. [Source: Laura S. Klar, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2006, metmuseum.org \^/]

In contrast to the Roman theater, which evolved from Greek models, the amphitheater had no architectural precedent in the Greek world. Likewise, the spectacles that took place in the amphitheater—gladiatorial combats and venationes (wild beast shows)—were Italic, not Greek, in origin. The earliest secure evidence for gladiatorial contests comes from the painted decoration of a fourth-century B.C. tomb at Paestum in southern Italy. Several ancient authors record that gladiatorial combat was introduced to Rome in 264 B.C., on the occasion of munera (funeral games) in honor of an elite citizen named D. Iunius Brutus Pera.

By the mid-first century B.C., gladiatorial contests were staged not only at funerals, but also at state-sponsored festivals (ludi). Throughout the imperial period, they remained an important route to popular favor for emperors and provincial leaders. In 325 A.D., Constantine, the first Christian emperor, prohibited gladiatorial combat on the grounds that it was too bloodthirsty for peacetime. Literary, epigraphic, and archaeological evidence indicates, however, that gladiatorial games continued at least until the mid-fifth century A.D.

See Separate Article: THEATERS, AMPHITHEATERS AND ARENAS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Baths in Ancient Rome

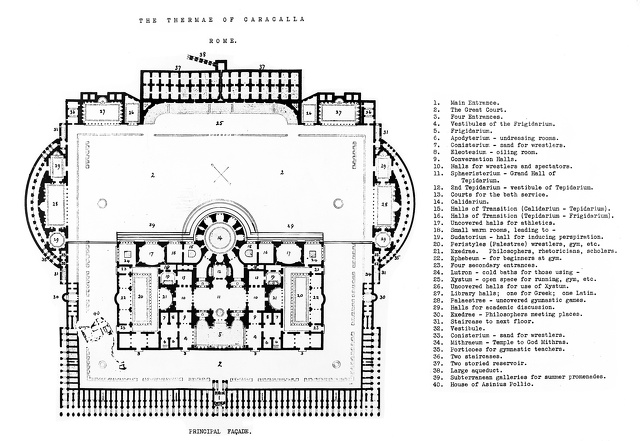

In ancient Rome, thermae were facilities for bathing. The term usually refers to large imperial bath complexes, with balneae refering to smaller-scale facilities. There were public and private thermae and they existed in great numbers throughout Rome. Most Roman cities had at least one and many urban areas had many of them. They were centers not only for bathing, but also socializing and relaxing as well. Bathhouses could also be found at wealthy private villas, town houses, and forts.

Roman public baths had a pubic sanitation system with water piped in and piped out. They were supplied with water from an adjacent river or stream, or within cities by aqueduct. The water would be heated by fire then channelled into different parts of the bath. The architecture of baths is discussed by Vitruvius in "De architectura." Baths at home were generally only big enough to sit up in and they were filled with water from pottery buckets by slaves. Baths proliferated all over the Roman Empire for both military and civilian use. Many were quite ornate, with huge colonnades, decorative mosaics and pools with different temperature water.

Most baths had the same essential elements: a changing room, a tepidarium (a sweating room and warm-water bathing hall), caldarium (hot-water bathing hall), laconicum ( super hot-water bathing hall), frigidarium (cold-water bathing hall), a large open hall, and an open-topped rotunda (with warm circulating air around it). Water was supplied to the baths through networks of underground pipes.

See Separate Article: BATHS IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Architecture under Augustus

Augustus (reigned 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) promoted learning, patronized the arts and turned Rome into a truly great imperial city. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “By the first century B.C., Rome was already the largest, richest, and most powerful city in the Mediterranean world. During the reign of Augustus, however, it was transformed into a truly imperial city. The emperor was recognized as chief state priest, and many statues depicted him in the act of prayer or sacrifice. Sculpted monuments, such as the Ara Pacis Augustae built between 14 and 9 B.C., testify to the high artistic achievements of imperial sculptors under Augustus and a keen awareness of the potency of political symbolism. [Source: Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2000, metmuseum.org \^/]

” Religious cults were revived, temples rebuilt, and a number of public ceremonies and customs reinstated. Craftsmen from all around the Mediterranean established workshops that were soon producing a range of objects—silverware, gems, glass—of the highest quality and originality. Great advances were made in architecture and civil engineering through the innovative use of space and materials. By 1 A.D., Rome was transformed from a city of modest brick and local stone into a metropolis of marble with an improved water and food supply system, more public amenities such as baths, and other public buildings and monuments worthy of an imperial capital.” \^/

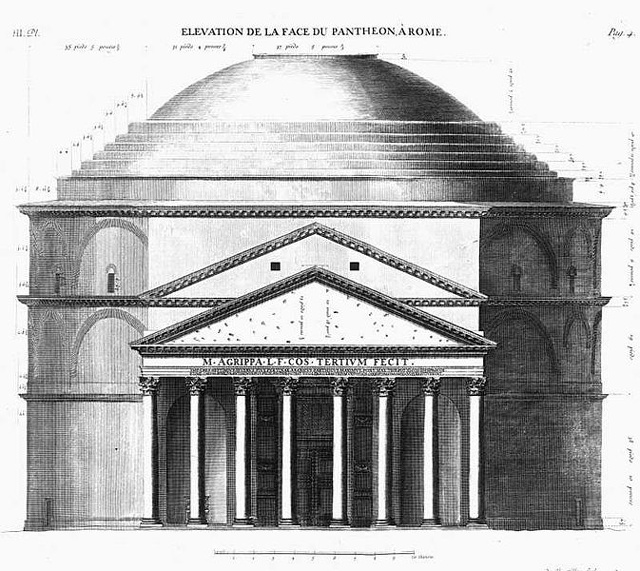

It is said that Augustus boasted that he “found Rome of brick and left it of marble.” He restored many of the temples and other buildings which had either fallen into decay or been destroyed during the riots of the civil war. On the Palatine hill he began the construction of the great imperial palace, which became the magnificent home of the Caesars. He built a new temple of Vesta, where the sacred fire of the city was kept burning. He erected a new temple to Apollo, to which was attached a library of Greek and Latin authors; also temples to Jupiter Tonans and to the Divine Julius. One of the noblest and most useful of the public works of the emperor was the new Forum of Augustus, near the old Roman Forum and the Forum of Julius. In this new Forum was erected the temple of Mars the Avenger (Mars Ultor), which Augustus built to commemorate the war by which he had avenged the death of Caesar. We must not forget to notice the massive Pantheon, the temple of all the gods, which is to-day the best preserved monument of the Augustan period. This was built by Agrippa, in the early part of Augustus’s reign (27 B.C.), but was altered to the form shown above by the emperor Hadrian (p. 267). [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUGUSTUS'S ACCOMPLISHMENTS: BUILDING CAMPAIGN, PUBLIC WORKS, THE ARTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS AS EMPEROR OF ROME: GOVERNING STYLE, WORSHIP, ADMINISTRATION europe.factsanddetails.com

Nero Rebuilds Rome After the Great Fire

The most lasting contribution of Nero (ruled from A.D. 54-68) was his rebuilding of Rome after the Great Fire of Rome in A.D. 64. Before the fire, Tacitus wrote, the great city was put together "indiscriminately and piecemeal." Afterwards, according to Nero's orders, Rome was rebuilt "in measured lines of streets, with broad thoroughfares, buildings of restricted height, and open spaces, while porticoes were added as protection to the front of the apartment-blocks...These porticoes Nero offered to erect at his own expense, and also to hand over his building sites, clear of rubbish, to the owners." He also established building codes that required new houses to be built with fire walls, and organized a fire department. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Tacitus wrote: “From the ashes of the fire rose a more spectacular Rome. A city made of marble and stone with wide streets, pedestrian arcades and ample supplies of water to quell any future blaze. The debris from the fire was used to fill the malaria-ridden marshes that had plagued the city for generations.

Narrow streets were widened, and more splendid buildings were erected. The vanity of the emperor was shown in the building of an enormous and meretricious palace, called the “golden house of Nero,” and also in the erection of a colossal statue of himself near the Palatine hill. To meet the expenses of these structures the provinces were obliged to contribute; and the cities and temples of Greece were plundered of their works of art to furnish the new buildings. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “In addition to the Gymnasium Neronis, the young emperor’s public building works included an amphitheater, a meat market, and a proposed canal that would connect Naples to Rome’s seaport at Ostia so as to bypass the unpredictable sea currents and ensure safe passage of the city’s food supply. Such undertakings cost money, which Roman emperors typically procured by raiding other countries. But Nero’s warless reign foreclosed this option. (Indeed, he had liberated Greece, declaring that the Greeks’ cultural contributions excused them from having to pay taxes to the empire.) Instead he elected to soak the rich with property taxes—and in the case of his great shipping canal, to seize their land altogether. The Senate refused to let him do so. Nero did what he could to circumvent the senators—“He would create these fake cases to bring some rich guy to trial and extract some heavy fine from him,” says Beste—but Nero was fast making enemies. One of them was his mother, Agrippina, who resented her loss of influence and therefore may have schemed to install her stepson, Britannicus, as the rightful heir to the throne. Another was his adviser Seneca, who was allegedly involved in a plot to kill Nero. By A.D. 65, mother, stepbrother, and consigliere had all been killed. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NERO (RULED A.D. 54-68) AS EMPEROR: EARLY PROMISE, REFORMS, LATER REVOLTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

GREAT FIRE OF ROME IN A.D. 64: NERO, EVIDENCE, STORIES, RUMORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S GOLDEN HOUSE AND THE REBUILDING ROME AFTER THE GREAT FIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

Sometimes concrete apartment buildings in the cites were built around a central courtyard with shops and wine taverns on the ground floor facing outward toward the streets

The Stabian Baths in Pompeii (near the Lupanar on Vi. dell'Abbondanza) is a large public bath with its marble floors and stucco ceilings. The rooms include a men's bath, women's bath, dressing room, “frigidaria” (cold bath), “tepidaria” (warm bath) and “caldaria” (steam bath). The Suburban Baths in Herculaneum is where The noblemen relaxed in indoor pools under skylights and wall paintings. The vaulted swimming pool and warm and hot baths there today are in excellent condition.

area around Fori Imperiali

Architecture under Trajan

Roman Art: During Trajan’s reign (98–117 A.D.) period Roman art reached its highest development. The art of the Romans, as we have before noticed, was modeled in great part after that of the Greeks. While lacking the fine sense of beauty which the Greeks possessed, the Romans yet expressed in a remarkable degree the ideas of massive strength and of imposing dignity. In their sculpture and painting they were least original, reproducing the figures of Greek deities, like those of Venus and Apollo, and Greek mythological scenes, as shown in the wall paintings at Pompeii. Roman sculpture is seen to good advantage in the statues and busts of the emperors, and in such reliefs as those on the arch of Titus and the column of Trajan. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

But it was in architecture that the Romans excelled; and by their splendid works they have taken rank among the world’s greatest builders. We have already seen the progress made during the later Republic and under Augustus. With Trajan, Rome became a city of magnificent public buildings. The architectural center of the city was the Roman Forum (see frontispiece), with the additional Forums of Julius, Augustus, Vespasian, Nerva, and Trajan. Surrounding these were the temples, the basilicas or halls of justice, porticoes, and other public buildings. The most conspicuous buildings which would attract the eyes of one standing in the Forum were the splendid temples of Jupiter and Juno upon the Capitoline hill. While it is true that the Romans obtained their chief ideas of architectural beauty from the Greeks, it is a question whether Athens, even in the time of Pericles, could have presented such a scene of imposing grandeur as did Rome in the time of Trajan and Hadrian, with its forums, temples, aqueducts, basilicas, palaces, porticoes, amphitheaters, theaters, circuses, baths, columns, triumphal arches, and tombs. \~\

RELATED ARTICLES:

TRAJAN (RULED A.D. 98-117): HIS CONQUESTS AND LETTERS ON HOW HE GOVERNED europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TRAJAN 'S CONQUEST OF THE DACIANS AND TRAJAN'S COLUMN europe.factsanddetails.com

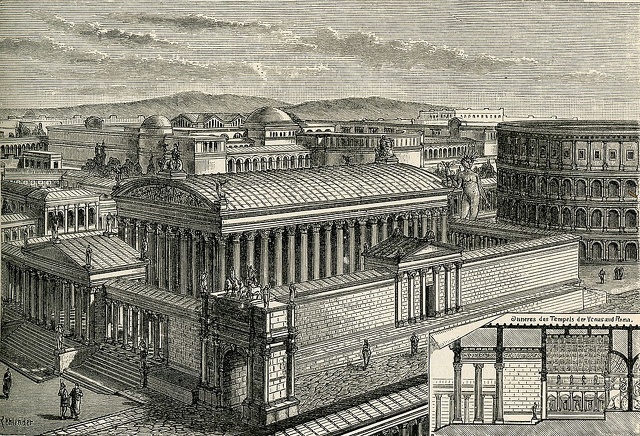

Hadrian, the Master Builder

Tom Dyckoff wrote in The Times: “And then there were his monuments: the Pantheon, that Temple of the Divine Trajan, the vast Temple of Venus and Roma, the only building for certain designed by Hadrian, his country estate at Tivoli and, to cap it all, his mausoleum – its ruins now assimilated into Rome’s Castel Sant’ Angelo. His wall in northern England was no exception, either. In the provinces, Hadrian bolstered defences, improved cities and built temples, along the way revolutionising the construction industry and securing jobs and prosperity for the plebs. Hail Hadrian, patron saint of hod-carriers. [Source: Tom Dyckoff, the Times, July 2008 ==]

“Hadrian’s architectural passions were the high point of the “Roman Architectural Revolution”, 200 years during which a genuinely Roman language of architecture emerged after several centuries of slavish copying of the Ancient Greek originals. At first the use of such novel materials as concrete and a newly rigid lime mortar was driven by the empire’s expansion, and the consequent demand for new large, practical structures – warehouses, record offices, proto-shopping arcades – easily and quickly put up by unskilled labour. But these new building types and materials also provoked experimentation – new shapes, such as the barrel vault and the arch – acquired from Rome’s expansion to the Middle East. == “Hadrian was, in architectural matters, both conservative and audacious. He was infamously respectful of Ancient Greece – comically so to some: he wore a Greek-style beard, and was nicknamed Graeculus. Many of the structures he put up, not least his own Temple of Venus and Roma, were faithful to the past. Yet the ruins of his estate at Tivoli, with its technical feats, its pumpkin domes, its space, curves and colour reveal a theme park of experimental structures that are still inspirational.” ==

Aelius Spartianus wrote: “In almost every city he built some building and gave public games. At Athens he exhibited in the stadium a hunt of a thousand wild beasts, but he never called away from Rome a single wild-beast-hunter or actor. In Rome, in addition to popular entertainments of unbounded extravagance, he gave spices to the people in honour of his mother-in-law, and in honour of Trajan he caused essences of balsam and saffron to be poured over the seats of the theatre. And in the theatre he presented plays of all kinds in the ancient manner and had the court-players appear before the public. In the Circus he had many wild beasts killed and often a whole hundred of lions. He often gave the people exhibitions of military Pyrrhic dances, and he frequently attended gladiatorial shows. He built public buildings in all places and without number, but he inscribed his own name on none of them except the temple of his father Trajan. [Source: Aelius Spartianus: Life of Hadrian,” (r. 117-138 CE.),William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West]

“At Rome he restored the Pantheon, the Voting-enclosure, the Basilica of Neptune, very many temples, the Forum of Augustus, the Baths of Agrippa, and dedicated all of them in the names of their original builders. Also he constructed the bridge named after himself, a tomb on the bank of the Tiber, and the temple of the Bona Dea. With the aid of the architect Decrianus he raised the Colossus and, keeping it in an upright position, moved it away from the place in which the Temple of Rome is now, though its weight was so vast that he had to furnish for the work as many as twenty-four elephants. This statue he then consecrated to the Sun, after removing the features of Nero, to whom it had previously been dedicated, and he also planned, with the assistance of the architect Apollodorus, to make a similar one for the Moon.

“Most democratic in his conversations, even with the very humble, he denounced all who, in the belief that they were thereby maintaining the imperial dignity, begrudged him the pleasure of such friendliness. In the Museum at Alexandria he propounded many questions to the teachers and answered himself what he had propounded. Marius Maximus says that he was naturally cruel and performed so many kindnesses only because he feared that he might meet the fate which had befallen Domitian.

“Though he cared nothing for inscriptions on his public works, he gave the name of Hadrianopolis to many cities, as, for example, even to Carthage and a section of Athens; and he also gave his name to aqueducts without number. He was the first to appoint a pleader for the privy-purse.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HADRIAN (RULED A.D. 117-138): HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND REIGN AS EMPEROR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HADRIAN'S BUILDING PROJECTS, TOURS AND DEFENSES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024