Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Economics and Agriculture

SLAVE TRADE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Slaves were also an important item of trade. When the Romans captured a town, its inhabitants were considered part of the booty, and those unable to pay ransom would be sold to a slave dealer who would take them to market. A successful campaign could bring in a flood of slaves. After Vespasian's son, Titus, suppressed the revolt in Judea in A.D. 70, large numbers of Jewish slaves were brought to Rome, where they helped build the Flavian amphitheater (Colosseum). [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

But as Rome's expansion ceased and the wars she fought became defensive, warfare provided the markets with fewer slaves. Piracy was another source of slavery, though the imperial fleet tried to keep it under control. Another source was unwanted children exposed by their parents. Slavers would pick them up, raise them, and then sell them as slaves. Slaves might also be bred: fertile slave women could be rewarded for bearing three or four children with exemption from work or freedom.

Slaves were an important item of foreign trade. The less civilized fringe regions of the empire sold surplus population to pay for merchandise from the empire. In particular, when Hadrian banned male castration within the empire, he created an import market for eunuchs, who were in demand particularly in the later period. Abasgia on the Black Sea became an important source of eunuchs until the emperor Justinian (527–56) put a stop to it; the king of Abasgia would seize handsome boys, castrate them and sell them to dealers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME: NUMBERS, LAWS, FREEDOM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF SLAVES AND SLAVE-LIKE PEOPLE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TREATMENT AND LIVING CONDITIONS OF SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

RUNAWAY SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, PUNISHMENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SLAVE REBELLIONS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTACUS AND THE GREAT ROMAN SLAVE REBELLION europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425" by Kyle Harper (2016) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Slaveries (Blackwell) by Eftychia Bathrellou and Kostas Vlassopoulos (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Material Life of Roman Slaves” by Sandra R. Joshel and Lauren Hackworth Petersen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Guide to Slave Management: A Treatise” by Nobleman Marcus Sidonius Falx

by Jerry Toner and Mary Beard (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Slavery and Its New Testament Contexts”

by Christy Cobb and Katherine A. Shaner (2025) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Slavery After Rome, 500-1100" (Oxford Studies) by Alice Rio (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Slavery (Routledge Sourcebook) by Thomas Wiedemann (1980) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery” by Peter Hunt (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Slave in Greece and Rome: (Wisconsin Studies in Classics)

by Jean Andreau , Raymond Descat, et al. (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Invention of Ancient Slavery” by Niall McKeown (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire” by Joyce Marcus (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 1, The Ancient Mediterranean World”

Book 1 of 4: by Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge (2011) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave Wars: A Brief History with Documents” by Brent D. Shaw (2001) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140 B.C.70 B.C.” by Keith R Bradley and K R Bradley (1989) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave Wars” by Hourly History Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave War 73–71 BC”, Illustrated, by Nic Fields and Steve Noon (2009) Amazon.com;

Impact of Slavery on the Ancient Roman Economy

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: From its heart in Italy across its many thousands of miles, the Roman Empire was built and maintained by slaves. Slaves toiled in all arenas of the Roman world, including homes, schools, fields, mines, construction projects, and even entertainment. A few, including the former gladiator Spartacus, even led rebellions against Rome. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Slaves were found in all areas of the Roman economy. They were used on farms, ranches, mines, and factories. Both the state and the imperial household owned slave crews to maintain the aqueducts. Slaves used in mining, which was an imperial monopoly, suffered terribly. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Freed slaves fed the citizen body with new blood; it brought in new immigrants and assimilated them. They made a significant contribution to Roman culture: the poet Horace was the son of a freedman, and Phaedrus was a Thracian slave who lived in Rome as a freedman in the house of Augustus, where he wrote his collection of fables. By the end of the second century, the great majority of Roman citizens must have had at least one slave in their family tree.

Extraordinary Number of Tasks Done by Roman Slaves

Slaves were involved in the collection of their taxes, the supervision of their general farms, the administration of their immense country properties, their mines, and their quarries of marble and porphyry. But even on the Palatine at Rome, where modern research has discovered, along with the graffiti of the paedagogium, the traces of their places of punishment, the imperial slaves must have been legion, if only to fulfil the incredible number of tasks which were entrusted to them, and which are revealed by their obituary inscriptions. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Reading these without prejudice, the student is dumbfounded by the extraordinary degree of specialisation they reveal, the insensate luxury and the meticulous etiquette which made this specialisation necessary. The emperor had as many categories of slaves to arrange and tend his wardrobe as he had separate types of clothes: for his palace garments the slaves a veste privata, for his city clothes the a veste jorensi, for his undress military uniforms the a veste castrensi, and for his full-dress parade uniforms the a veste triumphal, for the clothes he wore to the theater the a veste gladiatoria. His eating utensils were polished by as many teams of slaves as there were kinds: the eating vessels, the drinking vessels, the silver vessels, the golden vessels, the vessels of rock crystal, the vessels set with precious stones. His jewels were entrusted to a crowd of servi or liberti ab ornamentis, among whom were distinguished those in charge of his pins (the a fibulis) and those responsible for his pearls (the a margaritis). Several varieties of slaves competed over his toilet: the bathers (balneatores), the masseurs (aliptae), the hairdressers (ornatores), and the barbers (tons ores).

The ceremonial of his receptions was regulated by several kinds of ushers : the velarii who raised the curtains to let the visitor enter, the ab admissione who admitted him to the presence, the nomenclatores who called out the name. A heterogeneous troop were employed to cook his food, lay his table, and serve the dishes, ranging from the stokers of his furnaces (fornacarii) and the simple cooks' (cod) to his bakers (pistores), his pastry-cooks (libarii) and his sweetmeatmakers (dttlciarii), and including, apart from the majordomos responsible for ordering his meab (structores), the dining-room attendants (triclinarii), the waiters (ministratores) who carried in the dishes, the servants charged with removing them again (analectae), the cupbearers who offered him drink and who differed in importance according to whether they held the flagon (the a lagona) or presented the cup (the a cyatho), and finally the tasters (praegustatores), whose duty it was to test on themselves the perfect harmlessness of his food and drink and who were assuredly expected to perform their task more efficiently than the tasters of Claudius and Britannicus. Finally, for his recreation, the emperor had an embarrassing variety of choice between the songs of his choristers (symphoniaci), the music of his orchestra, the pirouettes of his dancing women (saltatrices), the jests of his dwarfs (nani), of his "chatterboxes" (fatui), and of his buffoons (moriones).

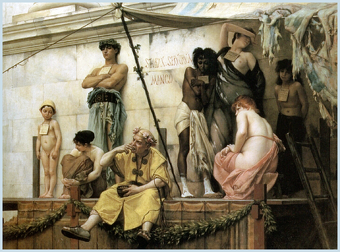

Sale of Slaves in Ancient Rome

Slave dealers usually offered their wares at public auction sales. These were under the supervision of the aediles, who appointed the place of the sales and made rules and regulations to govern them. A tax was imposed on imported slaves. They were offered for sale with their feet whitened with chalk; those from the East had their ears bored, a common sign of slavery among oriental peoples. When bids were to be asked for a slave, he was made to mount a stone or platform, corresponding to the “block” familiar to the readers of our own history. From his neck hung a scroll (titulus), setting forth his character and serving as a warrant for the purchaser. If the slave had defects not made known in this warrant, the vendor was bound to take him back within six months or make good the loss to the buyer. The chief items in the titulus were the age and nationality of the slave, and his freedom from such common defects as chronic ill-health, especially epilepsy, and tendencies to thievery, running away, and suicide. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In spite of the guarantee, the purchaser took care to examine the slaves as closely as possible. For this reason they were commonly stripped, made to move around, handled freely by the purchaser, and even examined by physicians. If no warrant was given by the dealer, a cap (pilleus) was put on the slave’s head at the time of the sale, and the purchaser took all risks. The dealer might also offer the slaves at private sale. This was the rule in the case of all slaves of unusual value and especially of those with marked personal beauty. These were not exposed to the gaze of the crowd, but were exhibited only to persons who were likely to purchase. Private sales and exchanges between citizens without the intervention of a regular dealer were as common as the sales of other property, and no stigma was attached to them. The trade of the mangones, on the other hand, was looked upon as utterly disreputable, but it was very lucrative and great fortunes were often made in it. Vilest of all the dealers were the lenones, who kept and sold women slaves for immoral purposes only. |+|

“Prices of Slaves. The prices of slaves varied as did the prices of other commodities. Much depended upon the times, the supply and demand, the characteristics and accomplishments of the particular slave, and the requirements of the purchaser. Captives bought upon the battlefield rarely brought more than nominal prices, because the sale was in a measure forced, and because the dealer was sure to lose a large part of his purchase on the long march to Rome, through disease, fatigue, and, especially, suicide. There is a famous piece of statuary representing a hopeless Gaul killing his wife and then himself. We are told that Lucullus once sold slaves in his camp at an average price of eighty cents each. In Rome male slaves varied in value from $100 paid for common laborers in the time of Horace, to $28,000 paid by Marcus Scaurus for an accomplished grammaticus. Handsome boys, well trained and educated, sold for as much as $4000. Very high prices were also paid for handsome and accomplished girls. It seems strange to us that slaves were matched in size and color as carefully as horses were once matched, and that a well-matched pair of boys would bring a much larger sum when sold together than when sold separately.” |+|

Sources of Slaves in the Roman Empire

captives

In ancient Rome, some slaves were born enslaved, the sons and daughters of enslaved mothers. Others were captives subjugated by the Roman army. Still others were bought and sold at slave markets. Under the Republic most slaves brought to Rome and offered there for sale were captives taken in war. The captives were sold as soon as possible after they were taken, in order that the general might be relieved of the trouble and risk of feeding and guarding such large numbers of men in a hostile country. The sale was conducted by a quaestor; the purchasers were the wholesale slave dealers that always followed an army, along with other traders and peddlers. A spear (hasta), which was always the sign of a sale conducted under public authority, was set up in the ground to mark the place of sale, and the captives had garlands on their heads, as did victims offered in sacrifice. Hence the expressions sub hasta venire and sub corona venire came to have practically the same meaning, “to be sold as slaves.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The wholesale dealers (mangones) assembled their purchases in convenient depots, and, when sufficient numbers had been collected, marched them to Rome, in chains and under guard, to be sold to local dealers or to private individuals. The slaves obtained in this way were usually men and likely to be physically sound and strong for the simple reason that they had been soldiers. On the other hand they were likely to prove intractable and ungovernable, and many preferred even suicide to servitude. It sometimes happened, of course, that the inhabitants of towns and whole districts were sold into slavery without distinction of age or sex. |+|

“Under the Empire large numbers of slaves came to Rome as articles of ordinary commerce, and Rome became one of the great slave marts of the world. Slaves were brought from all the provinces of the Empire: blacks came from Egypt, swift runners from Numidia, grammarians from Alexandria; those who made the best house servants came from Cyrene; handsome boys and girls, and well-trained scribes, accountants, amanuenses, and even teachers, came from Greece; experienced shepherds came from Epirus and Illyria; Cappadocia sent the most patient and enduring laborers. |+|

“Some of the slaves were captives taken in the petty wars that Rome was always waging in defense of her boundaries, but they were numerically insignificant. Others had been slaves in the countries from which they came, and merely exchanged old masters for new when they were sent to Rome. Still others were the victims of slave hunters, who preyed on weak and defenseless peoples two thousand years ago much as slave hunters are said to have done in Africa until very recent times. These man-hunts were not prevented, though perhaps not openly countenanced, by the Roman governors. |+|

“A less important source of supply was the natural increase in the slave population as men and women formed permanent connections with each other, called contubernia. This became of general importance only late in the Empire, because in earlier times, especially during the period of conquest, it was found cheaper to buy than to breed slaves. To the individual owner, however, the increase in his slaves in this way was a matter of as much interest as the increase in his flocks and herds. Such slaves would be more valuable at maturity, for they would be acclimated and less liable to disease, and, besides, would be trained from childhood in the performance of the very tasks for which they were destined. They would also have more love for their home and for their master’s family, since his children were often their playmates. It was only natural, therefore, for slaves born in the familia to have a claim upon their master’s confidence and consideration that others lacked, and it is not surprising that they were proverbially pert and forward. They were called vernae so long as they remained the property of their first master.” |+|

Determining Where Roman Slaves Came From

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: “Whence came these slaves? Some have presupposed that because two of the more important sources of slaves in the Republic - war and piracy - had become significantly restricted in the Empire there was a gradual diminution in the number of slaves during the first three centuries AD. However, there is no statistical proof of this, and for that reason Harris rejects it (rightly I believe), preferring to think that there was no serious drop in the number of slaves or in the demand for them - at least until A.D. 150. And since there is no evidence either that the cost of slaves spiralled upwards during this period, it seems sensible to infer that the supply of slaves needed annually to replenish the normal depletion of their numbers was more or less available without too much difficulty. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~]

“This raises two obvious but interesting questions: What number of new slaves was needed from year to year? Where did these replacements come from? “To answer the first of these questions we need to know the average length of time the slave spent as slave. This however, depends in turn on the average life expectancy of a slave. It has been estimated by Keith Hopkins that for the entire population the average life expectancy at birth was 20-30 years. Combining this figure with evidence from Roman tombstones Harris in turn estimates that the average life expectancy of a slave at birth in the Empire was unlikely to be more than 20 years. This seems reasonable, and since the average length of a slave's time as slave would be shorter than his average life expectancy at birth - partly because some slaves were manumitted and partly because some were not initially slaves but made so subsequently -it follows, if the number of slaves was to remain more or less constant as we have assumed, that the need for new slaves was exceptionally great. On these hypotheses Harris suggests that more than half a million were required annually for the first century and a half of the Empire. ~~

“Where did these slaves come from? The jurist gives a general answer: servi aut nascuntur, aut fiunt ['slaves are either born or made']. During the Republican period one of the principal sources (if not the principal source) of slaves had been prisoners of war. However, with the establishment of the principate under Augustus and the extension of the pax Romana across the Empire the significance of this source decreased. Yet, not completely of course: wars still continued but on a smaller scale. And there were even some major influxes of slaves from this source. The number of Jews enslaved as a result of the crushing of the Jewish rebellion by Vespasian and Titus (A.D. 66-70) was put (reliably, it would seem) at 97,000 by Josephus. The steady expansion in Britain continued to supply British slaves onto the market. Great numbers of prisoners of war reached Rome from the Dacian wars of Trajan is, however, an exaggeration). And after the Jewish revolt led by Bar-Cochba in A.D. 132-35 a large amount of Jews - well over 100,000, it is estimated - were sold as slaves in the East. ~~

“Roman soldiers involved in frontier wars and rebellions would have had many chances to buy prisoners of war as slaves at disposal auctions. Although this is not mentioned in the contemporary literature, it can be deduced from papyri which reveal slaves in the ownership of soldiers and veterans in Egypt. However, when Hadrian decided on a border plan of continuous defence along natural or man-made boundaries, these opportunities must have become far fewer. The effect on slave numbers of these various military episodes though significant was yet more short than long term. Harris, for example, thinks it improbable that in an average year for the period A.D. 14-150 more than 2%-3% (i.e. 10,000-15,000) of the slave requirement was supplied from prisoners of war. ~~

“Accordingly, we must turn our attention to the other sources of slaves in the early centuries of the Empire. Some have taken the view that, since the slave body at this period was already very great, the bulk of new slaves required each year would have been provided from their own class, i.e. that the slave body would have been almost self-propagating. Vernae (i.e. slaves born at home and kept within the familia - in Roman law any infant born to a slave woman was in turn a slave) - are certainly mentioned frequently in our sources. They were normally preferred by the Romans, who tended to get on well with them: their background was known, they spoke Latin from the beginning, they were accustomed to slavery knowing no other life, and they could be taught whatever skill their master intended for them. In particular, we have indications that they were encouraged to marry and have children, and in fact for our period the slave's type of marriage - contubernium - is well documented. Surely then, the argument goes, the number of new slaves needed annually would come for the most part from reproduction among the slaves themselves? ~~

“However, on closer analysis, this reasoning is flawed. True, some of the more fortunate city slaves and certain rural ones as well enjoyed a secure home life. And undoubtedly these together with the many female slaves who had children by their masters (or other free men) will have contributed considerably to the number of new slaves entering the system each year. Nevertheless, the belief that the total slave-body was more or less self-propagating is unsound. There are a number of reasons for this.” ~~

Were There More Male Slaves in the Roman Empire?

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: “One is the likelihood that the slave-body was disproportionately male. There is of course no clear statistical confirmation of this. However, if we allow for differences from one area to another and exclude entirely perhaps Roman Egypt the overall picture from the accessible evidence seems consistent. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~]

Selling Slaves in Rome by Jean Leon Gerome

“First of all it is clear that males were in the majority where work was difficult and weighty - in building, in mining, in numerous types of industry, in a wide variety of services such as loading and unloading at docks, portage, transportation, etc. In agriculture also male slaves would have been more in demand. Small landowners would have to be content with whatever slaves were available irrespective of their sex, while large landowners would undoubtedly have needed some female slaves e.g. for weaving, cloth making, cooking. However, it is clear from passages in Varro and Columella, where the question of which of the more reliable agricultural slaves should be allowed a female companion is treated, that permission for such a partner was a special concession. Varro recommended that praefecti ['overseers'], as an incentive to their faithfulness, should be granted female slaves with whom they could have children, while lesser slaves should have to do with less. In Columella, on the other hand, it is the vilicus ['steward'] who should be given a female partner. In the ergastula - the private prisons belonging to many Roman farms where slaves were forced to work in fetters - the inmates would have been very largely male. It is evident from this that among agricultural slaves males surely outnumbered females. ~~

“When we turn to domestic staff the evidence suggests that there too male slaves were more numerous. S. Treggiari in her analysis of the 79 members of the city household staff of Livia has noted that 77% were male (the percentage was similar among freedpersons and slaves). This is a very revealing figure since we would expect a domina to have a higher number of female staff than a dominus. And in her study of the city familiae of the Statilii and the Volusii Treggiari has shown that about 66% of the freedpersons and slaves were male, while of the thirty child slaves whose names were inscribed on the tombs of these two families 80% at a minimum were male. P.R.C. Weaver in his examination of the burial places of the imperial household stationed in Carthage calculated that 76% were males. One of the Oxyrhynchus papyri provides evidence of a big urban slave familia in Roman Egypt. It belonged to the wealthy Titus Julius Theon in Alexandria (died A.D. 111) and of fifty-nine slaves (at least) recorded as belonging to it a mere two were female. ~~

“In literature also there are occasional indications that it was more usual for private individuals to have male rather than female slaves : e.g. Horace, Sat. 1.6.116, has his meal served "by three servant boys" (pueris tribus); Naevolus in Juvenal, Sat. 9.64-7, owns "one servant boy" (puer unicus) and will have to get a second; in Lucian, Merc. Cond. (=On Salaried Posts in Great Houses) 32 both the cook and lady's hairdresser seem to be male; in the Cena of the Satyricon male slaves appear to be almost everywhere, c.f. e.g.. 27;28; 31;34. It would seem safe to conclude that in general, whenever slaves were bought, males outnumbered females, and that this was the pattern also for the total slave body of the Empire. Incidentally, there are, as Harris points out, parallels for this from the later Atlantic slave trade. For the period 1791-1798 there were 230 male slaves brought to Cuba compared to 100 female. And for Jamaica for the same period the ratio was 183 males to 100 females. ~~

“A second reason for the slave body's inability to propagate itself is linked to manumission. There is some evidence to suggest that female slaves were manumitted more often than males and marriageable females (it would seem) most often of all. The principal reason for this is thought to be marriage. Since the children of such a marriage were usually free, the emancipation of these nubile slaves would have removed the very individuals who were essential for the continuation of the class.” ~~

Did the Roman Slave Population Reproduce Itself?

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: ““Another reason for thinking that the slave population did not reproduce itself in sufficient numbers is that female slaves, on the available evidence (limited admittedly), do not seem to have been very prolific. Columella e.g. who refers to favours (such as a break from work) which he has granted to feminae fecundiores ['more fertile women'], includes mothers of three in this category. The implication is that in Italy the greater proportion of slave mothers gave birth to and reared at most two children. For the provinces unfortunately there is little reliable information. Even in Egypt the picture is obscure: the papyri do not seem to have been properly analysed with this question in mind. However, three or more children would appear to have been well above average for a slave woman there. P.Mich. V.326 mentions one slave mother of five children, but that is quite unusual. This apparently low fertility rate for Egypt is significant. There slaves brought in from abroad must have cost comparatively more than in the majority of other places across the empire. We would accordingly have expected even greater encouragement to procreation among slaves in Egypt than elsewhere. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~]

Captives in Rome by Charles Bartlett

“Another reason for doubting that the slave body was likely to reproduce itself is that even free peoples at certain periods found it hard to do so. Polybius e.g. discusses the decline of the population of Greece in his own day (mid 2nd century B.C.) and attributes this to two factors, childlessness and the scarcity of men. Much of southern Italy also experienced a decrease in its numbers towards the end of the Republic. Indeed, it is remarkable - given the prevalence of child-exposure, the limitations of obstetrics, diet and medicine, and the effects of wars, famines and the like - how buoyant the numbers of free peoples in general remained. ~~

“The evidence from slave populations elsewhere in history perhaps deserves mention here. In general this favours the argument that slave populations do not normally reproduce themselves. In the United States the reverse was true (there slave numbers increased after importation was banned in 1808), but that was a special case. For example, Brazil and the Caribbean imported more African slaves than North America, yet the slave body in both areas experienced a natural decline in numbers - up to 5% per annum depending on time and place. Why the United States was different is not clear, but a plausible suggestion is that the working and environmental conditions affecting the lives of slaves were more favourable there than elsewhere. It is unlikely that comparable conditions were to be found in the Roman Empire, and so we would expect the trend there to resemble that which prevailed later outside the U.S.A. ~~

“If these arguments are correct, vernae on their own will have failed by a significant amount to meet the annual requirements for new slaves. This shortfall, Harris, taking everything into account, estimated at several hundred thousand per year. ~~

“How was this shortfall made good? Where did the required number of new slaves originate? We must turn again to those who were made slaves. As well as prisoners of war there were other groups who belonged to this category. First, there were those who were kidnapped and sold into slavery. Both Augustus and Tiberius took measures against kidnapping. Augustus put a curb on grassatores ['bandits'] who used to capture travellers (both free and slave) and hand them over to landowners for retention in ergastula. However, in spite of the efforts of the two emperors kidnapping was not eradicated and persisted down to the next century. Yet, it would not have been so frequent and widespread that it could be considered a major source of new slaves in the early empire.” ~~

Were Pirates and Barbarians Major Sources of Slaves?

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: “The same can be said of piracy. This practice was considerably restricted when Pompey crushed the pirates after the passing of the Lex Gabinia in 67 B.C. and later when the moves against the piratical Illyrians came to a successful conclusion at the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Thereafter, the major section of the Mediterranean was rendered safe for journeying and commerce for the following two centuries by the creation and continued upkeep of the imperial fleet. However, some instances of piracy still occurred in the Mediterranean, cf. e.g. Lucian De Merc. Cond. 24. Outside the Mediterranean, where the auxiliary imperial squadrons were less active, pirates would have had more opportunities, cf. e.g. Strabo 11.496 for the Heniochi in the Black Sea. Nevertheless, it is improbable that piracy could ever have contributed a sizeable fraction of the slave numbers needed in the early centuries of the empire. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~]

“Another source of slaves was purchase from over the boundaries of the empire. Presumably this happened at all major limites, but its extent is impossible to determine. M. Crawford has made an attractive case for a series of such purchases in the late Republic. He argues that hoards of Republican denarii found in Dacia in the lower Danube basin are best explained as payments from c. 65 to 30 B.C. (i.e. after a hitherto significant source - piracy - had been suppressed by Pompey in 67 B.C.) by slave dealers/merchants to the local aristocracy. These latter (Crawford suggests) in exchange for sought-after commodities of the Mediterranean world such as silver and wine, sold off "perhaps [their] own humble dependants and certainly the humble dependants of others captured in internal raiding". ~~

“For the Empire Tacitus gives an instance for the lower Rhine in the reign of Domitian. Evidence for the practice can also be extrapolated from the Periplous Maris Erythraei , Strabo and two tariff inscriptions, one from Palmyra (A.D. 137), the other from Numidia (A.D. 202) . Yet, it is remarkable that when the place of origin of slaves is indicated in Roman literature, this is almost invariably from within rather than from without the Empire. And the papyri and inscriptions suggest the same pattern. Thus it is unlikely that slaves bought from beyond the frontiers would have been plentiful enough to meet a significant portion of the total slave needs of the early Empire. ~~

“What of the other sources of slaves? The sale of their own offspring by parents was one of these. This occurred particularly in hard times when parents attempted to ease their burden. The evidence for it, whether in literature or inscriptions, is sparse, yet we can presume that it did take place during the first centuries of the empire. However, the practice is unlikely to have been widespread. Philostratus says that it was a custom for the Phrygians "even to sell their children" - the inference being that this was rather exceptional. Tacitus tells how the Frisians in Lower Germany on being subjected to an excessive tribute by the Romans were forced eventually to sell their wives and children into slavery. This too however, would have been unusual. In general it is unlikely that even the most impoverished parents, once they had initially resolved to bring up a baby, would sell that baby into servitude - unless there was some very special provocation. ~~

“A few other methods of enslavement should also be mentioned here. The first was self-sale. Hermeros, for example, rather than remain a tribute-paying provincial and hoping subsequently to become a Roman citizen (i.e. tribute-free), seems to have sold himself into slavery. A second method was for debt. Here a debtor who was unable to pay could be "given up" (addictus ) to his creditor. A third method was penal enslavement i.e. slavery arising from conviction in law. Punishment for grave crimes could entail the removal of personal rights - the guilty being usually condemned to work as slaves in quarries or mines or as gladiators. However, it seems unlikely that any one of these methods, or indeed all three together, could have provided a significant number of slaves for our period. In fact, in the case of self-sale, its legality was never formally acknowledged in Roman law. ~~

“We can now pause here and take stock. Of all the sources so far discussed vernae were the most important. But even they, it has been suggested, left on average an annual deficit of several hundred thousand slaves. Since none of the other sources mentioned made significant dents in this number, we must ask "From where then did the main bulk of the remainder come?" Evidence points to "foundlings" - a source which, we may surmise, supplied considerably more slaves for our period than had been usually thought.” ~~

Abandonment of Infants: A Major Source of Roman Slaves?

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: “The abandonment of infants was widespread over much of the Roman world, and, no doubt, occurred even more frequently whenever circumstances became especially difficult. The custom was not made illegal until A.D. 374. Abandoned children usually either died or were made slaves, but the percentage in each group is beyond recall. In the case of the latter the owners themselves sometimes found the infants (either by accident of design); at other times they received them from finders who knew of their need. But there are also signs in the papyri of the availability of infants on request i.e. that individuals who were part of the slave trade nexus either collected abandoned babies for later sale themselves or bought them from others who found them. Sometimes owners engaged nurses under contract (a number of the relevant documents survive among the papyri) to look after foundlings in their early months. Occasionally foundlings were recovered by their parents. At other times if they could provide proof of their original citizen status and obtain a champion - an assertor - they could themselves initiate legal proceedings. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~] “Evidence for the practice of child-exposure in Rome and across the Empire is considerable. In his Roman Antiquities 2.15 Dionysius of Halicarnassus refers to a law of Romulus which obligated the Romans to raise all infant boys and the first-born infant girl, and prohibited the killing of any child under the age of three unless it was maimed or abnormal from birth. The likelihood is that this was not a real law but an invention in the late Republic in response to the worrying level of child-abandonment at the time. Tacitus considered it deserving of comment that the Germans and the Jews held it wrong to kill an unwanted child - the implication being that the Romans thought otherwise. Even the Roman aristocracy exposed children. Dio Cassius says that there were far more males than females among the nobility in Rome (in 18 B.C.), a ratio that can best be explained (given the number of males killed in the civil wars) by the abandonment of females at birth. This hypothesis receives support in Pliny, Pan. 26.5-27, where it is clear that not only did the poor need incentives to bring up their children but the rich did as well. Augustus would not allow the child born to Julia the Younger to be acknowledged and reared. ~~

“Elsewhere in many areas of the Roman world, we find child exposure widespread. It is securely documented for Roman Egypt, where two graphic phrases from the papyri deserve mention. The first is the legal description of the practice: " to rescue from the dung-pile for enslavement"; the second, the infamous advice of a husband in a letter to his wife in 1 B.C. :"If you do give birth, if it is male, let it live, if it is female, cast it out". (Needless to say, not all Egyptian-Greek couples thought like the husband here: infant boys too were abandoned there.) ~~

“Child-exposure was practised in Asia Minor, on the Greek mainland and on the Aegean islands. In Bithynia-Pontus for example in A.D. 111 during the governorship of Pliny the Younger the problem of the status and maintenance costs of enslaved foundlings became so serious that Pliny felt compelled to write to Trajan himself about the matter - and received from the emperor a letter in reply. Pliny's letter also reveals that similar kinds of problems had long caused concern in Achaea, for it refers to an edict of Augustus, and to letters of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian dealing with these matters there. Aelian, V.H. 2.7, thought it noteworthy that the citizens of Thebes attempted to put a stop to child-exposure. Plutarch, De amore prolis, stated bluntly: "poor people do not rear their children". Christian apologetic writers too (even though there may be exaggeration in their censure ) indicate that the practice remained widespread: cf. e.g. Tertullian, Apol. 9.7, "you (i.e. pagans) in more cruel fashion stifle your children's breath in water, or expose them to cold and hunger and dogs".. ~~

“Granted all of this, how important are we to rate foundlings as a slave source? Here we may recapitulate and conclude. When Tiberius and his successors followed in general Augustus' advice of confining the empire within its present frontiers, one of the principal sources of slaves i.e. prisoners of war, seriously decreased. However, as far as we are aware, no major emergency in the replenishment of slave numbers occurred. The reason surely is that the considerable range of other slave sources already available were together able to make up sufficiently for the shortfall. Yet, of these sources, only two, vernae and foundlings, could, we are convinced, have been major contributors. Vernae certainly were important, yet, if the arguments and estimates given above are sound, vernae would have fallen well short of supplying the full yearly requirement. That leaves foundlings. Since we know that child exposure was a widespread phenomenon - urban as well as rural - over a considerable section of the Greek world, Asia Minor, Egypt, Italy and elsewhere in the West, we may conclude that enslaved foundlings were more or less able to make up for the shortage in the slave supply caused by the drop in the numbers of prisoners of war in the first century and a half of the empire - a shortage which vernae and the other sources could not offset.” ~~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024