Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Economics and Agriculture

SLAVERY IN ANCIENT ROME

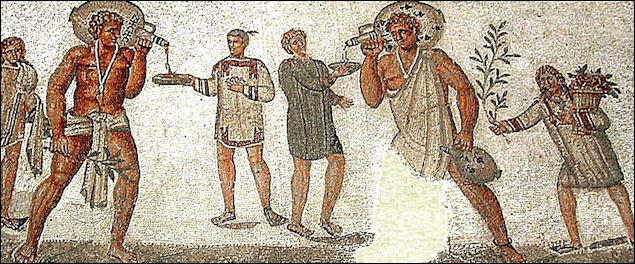

a slave with his master

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: Slaves had no rights; they could be flogged and subjected to physical or sexual abuse with impunity. If they ran away, they might be crucified if caught or sold to a producer of spectacles in the amphitheater where they would have to fight wild beasts. Household slaves generally got the best treatment, but even they were subject to harsh laws: if a slave killed his master, all the slaves in the house might be killed as punishment on the theory that protecting their master was their joint obligation and they had failed. The fear of slave revolt was always present, and harsh penalties were intended to enforce obedience. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

A typical household of a Roman citizen had one or two slaves. Wealthy people had more, including a full time cook and gardeners. The really rich had their own hairdressers and slaves that accompanied them whenever they went out. These slaves followed their masters everywhere and jumped to hold up mirrors and scratch the backs of their masters before they even had time to ask. The historian M.I. Finely observed, Romans “could not imagine a civilized existence to be possible” without slaves.

Dr Valerie Hope of the Open University wrote for the BBC: ““The main legal distinctions were between those who were free, and those who were slaves. All inhabitants of the empire were either free or in servitude. Slaves were either born into slavery, or were forced, often through defeat in war, into it. Slaves were the possessions of their masters and the latter had the power of life and death over them. Slavery was not, however, always a life-long state. Slaves could be - and regularly were - given their freedom. [Source: Dr Valerie Hope, BBC, March 29, 2011. |::|]

Because they they were suppressed little is known about them. Some estimates of slave numbers has them outnumbering freemen three to one. A slave revolt was a big worry among the upper classes (See See Separate Article on Spartacus and Slave Revolts). Slaves were not allowed to cover their heads. Freed slaves often wore a Phrygian (a cone-shaped hat) as a sign of their freedom. In the French Revolution, the idea was revived with bonnet rouge ("red cap"), or liberty cap.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SLAVE TRADE IN ANCIENT ROME: SOURCES, SALES AND ECONOMIC IMPACT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF SLAVES AND SLAVE-LIKE PEOPLE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TREATMENT AND LIVING CONDITIONS OF SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

RUNAWAY SLAVES IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, PUNISHMENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SLAVE REBELLIONS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTACUS AND THE GREAT ROMAN SLAVE REBELLION europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425" by Kyle Harper (2016) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Slaveries (Blackwell) by Eftychia Bathrellou and Kostas Vlassopoulos (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Material Life of Roman Slaves” by Sandra R. Joshel and Lauren Hackworth Petersen (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Guide to Slave Management: A Treatise” by Nobleman Marcus Sidonius Falx

by Jerry Toner and Mary Beard (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Slavery and Its New Testament Contexts”

by Christy Cobb and Katherine A. Shaner (2025) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Slavery After Rome, 500-1100" (Oxford Studies) by Alice Rio (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Slavery (Routledge Sourcebook) by Thomas Wiedemann (1980) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery” by Peter Hunt (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Slave in Greece and Rome: (Wisconsin Studies in Classics)

by Jean Andreau , Raymond Descat, et al. (2011) Amazon.com;

“Slaves and Masters in the Roman Empire: A Study in Social Control”

by K. R. Bradley (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Invention of Ancient Slavery” by Niall McKeown (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire” by Joyce Marcus (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 1, The Ancient Mediterranean World”

Book 1 of 4: by Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave Wars: A Brief History with Documents” by Brent D. Shaw (2001) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140 B.C.70 B.C.” by Keith R Bradley and K R Bradley (1989) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave Wars” by Hourly History Amazon.com;

“Spartacus and the Slave War 73–71 BC”, Illustrated, by Nic Fields and Steve Noon (2009) Amazon.com;

Slave Population of the Roman Empire

Probably over a quarter of the people living under ancient Roman rule were slaves. Keith Bradley of the University of Notre Dame told the BBC: “In Rome and Italy, in the four centuries between 200 B.C. and 200 AD, perhaps a quarter or even a third of the population was made up of slaves. Over time millions of men, women, and children lived their lives in a state of legal and social non-existence with no rights of any kind. They were non-persons” — many did not even have names — “and they couldn't own anything, marry, or have legitimate families. [Source: Professor Keith Bradley, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Their role was to provide labour, or to add to their owners' social standing as visible symbols of wealth, or both. Some slaves were treated well, but there were few restraints on their owners' powers, and physical punishment and sexual abuse were common. Owners thought of their slaves as enemies. By definition slavery was a brutal, violent and dehumanising institution, where slaves were seen as akin to animals. |::|

“Few records have survived from Roman slaves to allow modern historians to deduce from them a slave's perception of his or her life of servitude. Rome produced no slaves-turned-abolitionist such as the African-Americans Frederick Douglass or Harriet Jacobs. Instead the evidence available comes overwhelmingly from people such as Plutarch, who represented the slave-owning classes. But that evidence does show that Roman slaves managed to demonstrate their opposition to slavery in various ways.” |::|

Roman Slave Society

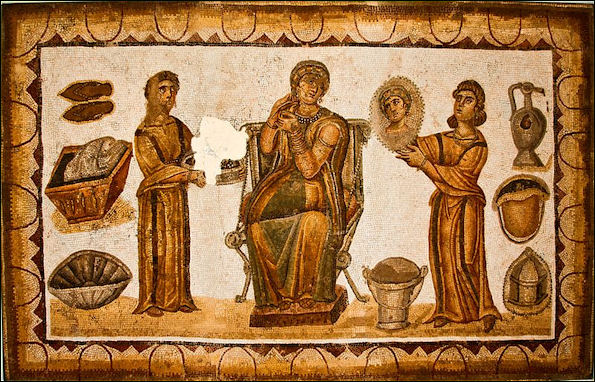

Man and woman and slave making a sacrifice

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill of the University of Reading wrote for the BBC: “One element, which perhaps more than others seems to separate our world from that of the Roman Empire, is the prevalence of slavery which conditioned most aspects of Roman society and economy. Unlike American plantation slavery, it did not divide populations of different race and colour but was a prime outcome of conquest. [Source: Professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Slavery required the systematic use of physical punishment, judicial torture and spectacular execution. From the crucifixion of rebel slaves in their thousands to the use of theatrical enactments of gruesome deaths in the arena as a form of entertainment, we see a world in which brutality was not only normal, but a necessary part of the system. And since the Roman economy was so deeply dependent on slave labour, whether in chained gangs in the fields, or in craft and production in the cities, we cannot wonder that modern technological revolutions driven by reduction of labour costs had no place in their world. |::|

“The system that seems to us manifestly intolerable was in fact tolerated for centuries, provoking only isolated instances of rebellion in slave wars and no significant literature of protest. What made it tolerable to them? One key answer is that Roman slavery legally allowed freedom and the transfer of status to full citizen rights at the moment of manumission. |::|

“Serried ranks of tombstones belonging to liberti (freed slaves, promoted to the master class), who flourished (only the lucky ones put up such tombs) in the world of commerce and business, indicate the power of the incentive to work with the system, not rebel against it. Trimalchio, the memorable creation of Petronius's Satyricon, is the caricature of this phenomenon. Roman society was acutely aware of its own paradoxes: the freedmen and slaves who served the emperors became figures of exceptional power and influence to whom even the grandees had to pay court.” |::|

History of Slavery in Ancient Rome

Semetic slave in ancient Egypt

So far as we may learn from history and legend, slavery was always known at Rome. In the early days of the Republic, however, the farm was the only place where slaves were employed. The fact that most of the Romans were farmers and that they and their free laborers were constantly called from the fields to fight the battles of their country led to a gradual increase in the number of slaves, until slaves were far more numerous than the free laborers who worked for hire. We cannot tell when the custom became general of employing slaves in personal service and in industrial pursuits, but it was one of the grossest evils resulting from Rome’s foreign conquests. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“In the last century of the Republic not only most of the manual labor and many trades but also certain of what we now call professions were in the hands of slaves and freedmen. The wages and living conditions of free labor were determined by the necessity of competition with slave labor. Further, every occupation in which slaves engaged was degraded in the eyes of men of free descent until all manual labor was looked upon as dishonorable. The small farms were more and more absorbed in the vast estates of the rich; the sturdy native yeomanry of Rome grew fewer from the constant wars, and were supplanted by foreign stock with the increase of slavery and frequency of manumission. By the time of Augustus most of the free-born citizens who were not soldiers were either slaveholders themselves or the idle proletariat of the cities, and the plebeian classes were largely of foreign, not Italian, descent. |+|

“Ruinous as were the economic results of slavery, the moral effects were no less destructive. To slavery more than to any other one factor is due the change in the character of the Romans in the first century of the Empire. With slaves swarming in their houses, ministering to their love of luxury, pandering to their appetites, directing their amusements, managing their business, and even educating their children, it is no wonder that the old virtues of the Romans, simplicity, frugality, and temperance, declined and perished. And with the passing of Roman manhood into oriental effeminacy began the passing of Roman sway over the civilized world.” |+|

Plight of Slaves and Ordinary People in Roman Society

In a review of Robert Knapp’s “Invisible Romans”, Adam Kirsch wrote in The New Yorker: “Even slaves, Knapp shows, were not without hopes and ambitions: “A slave identity was a combination of what was imposed upon him and what he could fashion for himself,” for instance, by saving money or learning a valuable skill in order to bargain for his freedom. Knapp wants to remind us that a Roman slave “remained a thinking, feeling, active human being”—a fact that few would deny but which is easy to forget when reading about the exploits of their owners. [Source: Adam Kirsch, The New Yorker, January 2, 2012]

“Still, these are meagre sparks of light in an overwhelmingly dark picture. “Invisible Romans” is full of anecdotes and quotations that speak volumes about Roman attitudes toward women, slaves, and the cheapness of human life in general. There is the story told by Pliny the Elder about an auctioneer who was selling a hugely expensive candelabra; to sweeten the deal, he “threw in as a free bonus a slave named Clesippus, a humpbacked fuller, and a fellow of surpassing ugliness.” There is the skeleton discovered in North Africa wearing a slave collar inscribed “This is a cheating whore! Seize her because she escaped from Bulla Regia!” And the casual aside in one of Cicero’s speeches in defense of his friend Plancius: “They say you and a bunch of young men raped a mime in the town of Atina—but such an act is an old right when it comes to actors, especially out in the sticks.”

ancient Greek slave helping a vomiting drunk man

“In general, the lot of the ordinary Roman was no different from that of the vast majority of human beings before the modern age: powerlessness, bitterly hard work, and the constant presence of death. The thing that strikes Knapp most about Roman popular wisdom is its deep passivity in the face of these afflictions, which feels so alien to moderns and especially to Americans. The Romans, he writes, had no concept of progress: “The implication is that the order of the universe is static, that social perspectives do not change; they must be the way they are. The ‘is’ and ‘ought to be’ of the world are the same.”

“Thus, a slave might dream of manumission but hardly of abolition. For women, “there were no alternative lifestyles and aspirations either offered or considered—no inkling that Romano-Grecian women ever conceived of a world different from the one they were born into.” In such a harsh world, being a soldier—one of the legionaries Polybius mentions, slicing up humans and animals—was actually one of the easier fates: “The army was the only institution in the Roman world that could more or less guarantee social as well as financial advancement if one worked hard and lived long enough.” Even the amenities of the Roman world, like the famous public baths, lose their lustre in Knapp’s grimly realistic portrait: “The baths offered not only social interaction but a lack of hygiene shocking even to contemplate . . . whatever dirt, grime, bodily fluids, expulsions, and germs people brought with them to the baths, the water quickly shared with other bathers.”

Numbers of Slaves in the Roman Empire

We have almost no testimony as to the number of slaves in Italy, none even as to the ratio of the free to the servile population. We have indirect evidence enough, however, to make good the statements in the preceding paragraphs. That slaves were few in early times is shown by their names; if it had been usual for a master to have more than one slave, such names as Marcipor and Olipor would not have sufficed to distinguish them. An idea of the rapid increase in the number of slaves after the Punic Wars may be gained from the number of captives sold into slavery by successful generals. Scipio Aemilianus is said to have disposed in this way of 60,000 Carthaginians, Marius of 140,000 Cimbri, Aemilius Paulus of 150,000 Greeks, Pompeius and Caesar together of more than a million Asiatics and Gauls. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The very insurrections of the slaves, unsuccessful though they always were, also testify to their overwhelming numbers. Of the two in Sicily, the first lasted from 134 to 132 B.C., the second from 102 to 98 B.C., in spite of the fact that at the close of the first the consul Rupilius had crucified 20,000, whom he had taken alive, as a warning to others to submit in silence to their servitude. Spartacus defied the armies of Rome for two years, and in the decisive battle with Crassus (71 B.C.) left 60,000 dead upon the field. Cicero’s orations against Catiline show clearly that it was the calling out of the hordes of slaves by the conspirators that was most dreaded in the city. |+|

“About the number of slaves under the Empire we may get some idea from more direct testimony. Horace implies that ten slaves were as few as a gentleman in even moderate circumstances could afford to own. He himself had two in town and eight on his little Sabine farm, though he was a poor man and his father had been a slave. Tacitus tells us of a city prefect who had four hundred slaves in his mansion. Pliny the Elder says that one Caius Caecilius Claudius Isodorus left at his death over four thousand slaves. Athenaeus (170-230 A.D.) gives us to understand that individuals owned as many as ten thousand and twenty thousand. The fact that house slaves were sometimes divided into “groups of ten” (decuriae) indicates how numerous slaves were. We have, indeed, no means of determining the free population of Rome at any period.” |+|

U.S. history offers enlightening parallels. The famous 18th century Virginian slave owner, “King” Carter, at is said to have used about a thousand slaves on his 300,000-acre estate. On his plantations slaves were worked in groups of thirty or fewer with a slave foreman and a white overseer. Nathaniel Heyward of South Carolina, who died in 1851, possessed 14 plantations and 2087 slaves.

Slaves serving their masters on a Tunisian mosaic

Guessing the Number of Slaves in the Roman Empire

John Madden of the University College Galway wrote: “Though slavery was a prevailing feature of all Mediterranean countries in antiquity, the Romans had more slaves and depended more on them than any other people. It is impossible, however, to put an accurate figure on the number of slaves owned by the Romans at any given period: for the early Empire with which we are concerned conditions varied from time to time and from place to place. Yet, some estimates for Rome, Italy, and the Empire are worth attempting. The largest numbers were of course in Italy and especially in the capital itself. In Rome there were great numbers in the imperial household and in the civil service - the normal staff on the aqueducts alone numbered 700. [Source: “Slavery in the Roman Empire Numbers and Origins” by John Madden, University College Galway, Classics Ireland, 1996 Volume 3, University College Dublin, Ireland ~~]

“Certain rich private individuals too had large numbers - as much for ostentation as for work . Pedanius Secundus, City Prefect in A.D. 61, kept 400 slaves, Gaius Caecilius Isidorus, freedman of Gaius Caecilius, left 4116 in his will in 8 B.C., while some owners had so many that a nomenclator had to be used to identify them. However, there is evidence to suggest that these cases were not typical - even for great houses. Sepulchral inscriptions for the rich noble gens the Statilii list a total of approximately 428 slaves and freedpersons from 40 B.C. to A.D. 65. When these figures are analysed, the number of slaves and freedpersons definitely owned by individual members of the gens is small, e.g. Statilius Taurus Sisenna (consul of A.D. 16) and his son had six, Statilius Taurus Corvinus (consul ordinarius of A.D. 45) had eight, and Statilia Messalina, wife of Nero, four or five. Seneca, a man of extraordinary wealth, believed he was travelling frugally when he had with him one cartload of slaves (most likely four or five). References in Juvenal and the Scriptores Historiae Augustae suggest that many non-plebeian Romans had either no slave or merely one or two. From evidence such as this Westermann, Hopkins and others are understandably cautious when attempting to come to a total figure for slaves in the city of Rome in the 1st century AD. Hopkins' estimate of 300,000-350,000 out of a population of about 900,000-950,000 at the time of Augustus seems plausible. ~~

“The same kind of caution needs to be exercised in attempting to arrive at a figure for slaves in Italy for the same period. Passages in the Satyricon would suggest that some households had vast numbers. But that work is of course fiction - though the references to slave numbers there can only have point if certain private individuals did own a lot of slaves. Overall, a figure of around two million slaves out of a population of about six million at the time of Augustus would perhaps seem right (again we follow Hopkins). If so, approximately one in every three persons in Rome and Italy was a slave. ~~

“And what of the Empire as a whole for this period? It is impossible to give any kind of accurate figure. We have neither statistics for the total area nor for the provinces separately. And of course the number of slaves in each province depended on the particular circumstances prevailing there. Some provincial locations had a high number of slaves: Pergamum in the 2nd century A.D. (we deduce this from Galen De Propr. Anim. 9) had 40,000 adult slaves and these formed (as at Rome) one third of the adult population. At Oea (Tripoli) in Africa also in the 2nd century A.D. the wife of Apuleius owned a familia of slaves well in excess of four hundred . However, other areas in the Empire had comparatively few slaves. The evidence from papyri suggests that in all likelihood slaves in Egypt never rose much above 10% of the population and in poorer areas there dropped to as low as 2%. And in other regions, particularly perhaps in the more backward provinces of the West, slaves may never have comprised a significant segment of the work force at all. What then might we assume as an approximate number of slaves in the entire empire in this period? The attractive hypothesis of Harris is ten million, i.e. 16.6%-20% of the estimated entire population of the Empire in the first century AD, i.e. one in every five or six persons would have been a slave. This of course is not a computation, merely a conjecture.” ~~

Depiction of slaves on a Carthage mosaic

Slave Numbers — Middle Versus Upper Class Roman Households

At the beginning of the second century B.C. houses in the Urbs which could boast of more than one slave were rare. This is proved by the custom of adding the suffix -por (=puer) to the genitive of the master's name to designate a slave: Lucipor, the slave of Lucius; Marcipor, the slave of Marcus. In contrast, during the second century A.D. there existed practically no masters of only one slave. People either bought no slave at all for the belly of a slave took a lot of filling or they bought and kept several together, which is why Juvenal in the verses already quoted uses the word "belly" in the plural: "... magno servorum venires!" [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Two slaves to carry him to the circus was the very minimum with which the disillusioned old reprobate whose moderation we have appreciated above could manage to get along. But the average was four or five times as many. The humblest householder could not hold his head up unless he could appear with a train of eight slaves behind him. Martial records that the miser Cimber arranged for eight Syrian slaves to carry the microscopic loads of his contemptible little gifts at the Saturnalia. And according to Juvenal a litigant would have thought his case already lost if it had been entrusted to an advocate not accompanied to the bar by a train of slaves of at least this size. A squad of eight was usually sufficient for a petit bourgeois. The man of the upper.middle classes on the other hand commanded a battalion or more. Not to be completely swamped by the number of their retainers, they divided them into two parties, one of which they employed in the Urbs and one in the country; and they redivided the town staff again into two, those who served indoors (servi atrienses) and those who served without (cursores, viatores).

Finally, these different batches were again divided into tens, each decuria being distinguished by a number. Even these precautions were unavailing. Master and slaves ended by not knowing each other by sight. In the very middle of his banquet Trimalchio fails to know which of his slaves he is giving orders to: "What decuria do you belong to?" he asks the cook. "The fortieth," answers the slave. "Bought or born in the house?" "Neither," is the reply. "I was left you under Pansa's will." "Well, then, mind you serve this carefully, or I will have you degraded to the messengers' decuria" Reading such a dialogue, one can easily imagine that scarcely one slave in ten among Trimalchio's hordes really knew his master. One gathers that there were at least 400 of them, but the fact that Petronius alludes only to the fortieth decuria is no proof that there were not many more. Pliny the Younger who, as we have seen, was at least poorer than Trimalchio by a matter of 10,000,000 sesterces had at least 500 slaves, for his will manumitted 100; and the law Fufia Caninia, probably passed in 2 B.C. and still in force in the second century A.D., expressly permitted owners of between 100 and 500 slaves to set one-fifth free, and forbade owners of larger numbers to emancipate more than 100.

It is impossible to repress our amazement in the face of figures so.extravagant; yet it is known that in the second century they were often exceeded. The surprise felt by the jurist Gaius a century and a half after the passing of the law Fufia Caninia to think that it had not extended its scale of testamentary manumission beyond 100 per 500 slaves, is a sure indication that the scale had no longer fitted the reality. Toward the end of the first century A.D. under the Flavians the freedman around Caelius Isidorus left 4,116 slaves, and while this figure for a private individual was sufficiently noteworthy to be judged worthy of mention by the elder Pliny, there is no doubt whatever that the familiae serviles in the service of the great Roman capitalists often reached 1,000, and that the emperor, infinitely more wealthy than the richest of them, must easily have possessed a "slave family" of 20,000.

Manumission (Release from Slavery) in Ancient Rome

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: One of the remarkable features of the Roman system of slavery was the frequency with which slaves were freed. It was not motivated simply by generosity. The prospect of freedom kept a slave docile and motivated him to serve his master faithfully. Manumission could also be profitable, for some owners would free their slaves only if they bought their freedom with their savings, thus allowing their owners to recoup the purchase price. A manumitted slave (libertus) was given a freedman's cap, a felt cap shaped like half an egg that fit close to the head, as a sign of freedom; the slave took the family name of his former master, who was now his patron, and became a Roman citizen. But a freed person was not free of obligations to his or her former master. The system was not without advantages for the libertus, who became a member of his former owner's familia and could be buried in the family plot. Moreover, he might go into business with his patron's backing and become wealthy. The Satyricon of Petronius describes a banquet offered by a freedman, Trimalchio, which is a vulgar display of new wealth, and freedmen like him cannot have been too uncommon. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

A slave might purchase freedom from his master by means of his savings, as we have seen, or he might be set free as a reward for faithful service or some special act of devotion. In either case it was only necessary for the master to pronounce him free in the presence of witnesses, though a formal act of manumission often took place before a praetor. The new-made freedman set on his head the cap of liberty (pilleus), seen on some Roman coins. He was called libertus in reference to his master or as an individual, libertinus as one of a class; his master was now not his dominus, but his patronus. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The relation that existed between the master and the freedman was one of mutual helpfulness. The patron assisted the freedman in business, often supplying the means with which he was to make a start in his new life. If the freedman died first, the patron paid the expenses of a decent funeral and had the body buried near the spot where his own ashes would be laid. He became the guardian of the freedman’s children; if no heirs were left, he himself inherited the property. The freedman was bound to show his patron marked deference and respect at all times, to attend him upon public occasions, to assist him in case of reverse of fortune, and in short to stand to him in the same relation as the client had stood to the patron in the brave days of old.” |+|

Laws on Marriage Involving Freed Roman Slaves

captives

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Roman law developed as a mixture of laws, senatorial consults, imperial decrees, case law, and opinions issued by jurists. One of the most long lasting of actions” of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian' (A.D. 482-566) “was the gathering of these materials in the 530s into a single collection, later known as the Corpus Iuris Civilis [The Code of Civil Law]. The texts here address the issue of marriage, and date back particularly to the time of Augustus [ruled 27 B.C. - A.D. 14] who was very concerned about family matters and ensuring a large population. In the selections that follow the first part comes from the Digest and contain the opinions on marriage law of famous lawyers - Marcianus, Paulus, Terentius Clemens, Celsus, Modestinus, Gaius, Papinianus, Marcellus, Ulpianus, and Macer. Note that the most important were Papinianus (executed by the Emperor Caracalla in 212), who excelled at setting forth legal problems arising from cases, and Ulpianus (d. 223), who wrote a commentary on Roman law in his era. All these were legal scholars of the Roman imperial period whose works were considered important enough to keep in the Digest. The second section, from the Codex contain the later receipts of emperors concerning marriage law and punishments. IN the Corpus individual authors were identified, and these names have been kept here. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329]

Celsus, Digest, Book XXX: It is provided by the Lex Papia that all freeborn men, except senators an their children, can marry freedwomen. Modestinus, Rules, Book II. A son who has been emancipated can marry without the consent of his father, and any son that he may have will be his heir. Marcianus, Institutes, Book X: A patron cannot marry his freedwoman against her consent. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329]

Ulpianus, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book III: In that law which provides that where a freedwoman has been married to her patron, after separation from him she cannot marry another without his consent; we understand the patron to be one who has bought a female slave under the condition of manumitting her (as is stated in the Rescript of our Emperor and his father), because, after having been manumitted, she becomes the freedwoman of the purchaser.” [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

Archaeology and Roman Slavery

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Roman slaves are nearly invisible in the archaeological record. They had few if any possessions, are rarely identified in texts, and their burials are seldom marked with a gravestone. “Slavery is a profound part of the Roman world and completely endemic,” says archaeologist Michael Marshall of Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). “But especially for Roman Britain, people have avoided talking about or investigating it because of the lack of texts and the complexity of the issue of slavery.” A unique burial discovered in central England’s Midlands region may be the first step to changing that. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2021

manumission

Several years ago, during work on a greenhouse at a home in the village of Great Casterton, builders unearthed an adult male skeleton, which was then excavated by a MOLA team. The man was lying on his right side and had heavy iron fetters secured by a padlock around his ankles. His remains were radiocarbon dated to between A.D. 226 and 427, a period during which, until the very last years, the Romans occupied Britain. Earlier excavations about 200 feet away had revealed a well-planned third to fourth-century A.D. cemetery filled with 133 burials, at least some in wooden coffins. The man’s skeleton, however, had been tossed into a ditch at the time of his death between the ages of 26 and 35. His twisted body, the unnatural position of his left arm over his head, and the absence of scavenging animals’ tooth marks — which likely would have been visible on his bones had his body been exposed for any length of time — all suggested the man was buried quickly and with little care. Although his skeleton is well preserved, indicating he was five feet five inches tall — average for the period — his head is missing, likely an accidental casualty of modern construction work. Marshall and MOLA osteoarchaeologist Chris Chinnock immediately wondered if the man had been a slave, which would make him the first Roman slave to be archaeologically excavated in Britain. But in the absence of a clear methodology for recognizing Roman slavery in the archaeological record, how would they know?

“The suggestion of slavery, punishment, or something nefarious immediately leapt to mind,” says Chinnock. Despite the fetters’ dramatic appearance, they do not definitively prove that the man was enslaved. This type of shackle has rarely been found anywhere in the Roman world, and never in Roman Britain. When Chinnock examined the skeleton to reconstruct the man’s life based on his bones, creating what scholars call an osteobiography, he found some lesions on his ankles and tibias from infections or trauma, but nothing that conclusively linked them to the fetters. He also found a bony spur on the man’s left femur. “The spur is of a type that can occur from a traumatic injury or from the repetitive activities of an active lifestyle, hard labor, or even heavy contact sports,” says Chinnock. “Nothing screams that this person was enslaved.” Furthermore, the man was buried near a thriving Roman town, and there would have been both slaves and laborers in the surrounding fields, farms, and villages. Still, says Marshall, the Great Casterton burial is “about the best evidence you could have for the social phenomenon of slavery.” “We don’t see the physical evidence of enslavement very often, so it evokes an immediate response,” says Chinnock. “This was an actual person, and he is valuable as an individual.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024