Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society / Culture and Sports / Literature and Drama

ANCIENT GREEK WRITTEN LANGUAGE

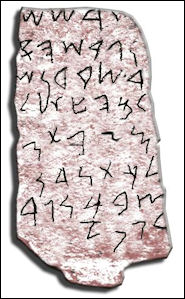

Phoenician alphabet According to the ancient Greeks they adapted their alphabet from the Phoenicians. Both were great seafaring peoples and eager to trade not only goods but ideas. One of the most important ideas was the alphabet. It enabled a system of writing by which they could record their transactions- 100 jars of olive oil, 20 blocks of white marble, 30 packages of purple dye, etc. As with other ideas they borrowed the Greeks made improvements, increasing the number of letters by adding vowels. This happened sometime around the beginning of the eighth century B.C. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

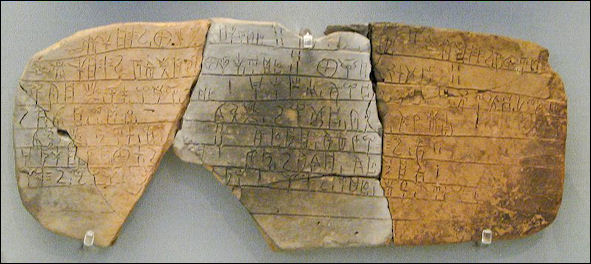

“This was not the first time that Greek speaking peoples had used a written language. The Mycenaeans, who were the subjects of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, had developed a system of writing that today's scholars call “Linear B”. Several thousand sun-dried clay tablets covered with the Linear B script have been found on the island of Crete. They represent the earliest form of written Greek known. Deciphered by a young English architect (Michael Ventris), the tablets recorded details about the storage and distribution of household goods. The information was probably written around 1400 B.C. . Then, during the Dark Age, the knowledge of writing died out. The Greeks became an illiterate society. |

“With the adoption and modification of the Phoenician alphabet the Greeks were on their way to becoming literate again. In fact the achievements for which they became renowned in fields as varied as philosophy, science, government, literature and medicine would not have happened if it weren't for writing. Socrates wrote nothing but we know so much about what he thought and said because of the writings of Plato. Access to a simple writing system meant that everyone willing to learn could, in theory, do so –women, slaves, peasants as well as members of the aristocracy. In fact, however, most didn't and illiteracy was widespread during the golden age of Greece- the Classical Era. |

“The Mycenaean Greeks used sharp instruments to engrave their language into wet clay tablets. (A major fire at an ancient palace baked thousands of these tablets and preserved them for scholars today.) Later Greeks used a variety of writing implements- papyrus (which they got from Phoenician traders), parchment (which was made from the scraped hides of cattle, ship or goats), wooden tablets whitened with gypsum, wooden tablets coated with wax and, of course, more durable materials such as stone monuments and bronze plaques. These more permanent materials were often used for official inscriptions- laws of the city, treaties with other states, temple dedications, war memorials and such. |

“Early Greek writing runs from right to left- for the first line. The second line then runs from left to right and the direction of the lines alternate for the complete text. This kind of writing is called boustrophedon (as the ox turns- when he plows a field.) Later the left to right system, which we use today, became the standard.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Writing Greek: An Introduction to Writing in the Language of Classical Athens”

by John Taylor and Stephen Anderson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek Writing from Knossos to Homer: A Linguistic Interpretation of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and the Continuity of Ancient Greek Literacy” by Roger D. Woodard (1997) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Writing in the Græco-Roman East” by Roger S. S Bagnall (2012) Amazon.com;

“Letter Writing in Greco-Roman Antiquity” by Stanley K. Stowers (1986) Amazon.com;

“Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet From A to Z” by David Sacks (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Decipherment of Linear B” by John Chadwick (1958) Amazon.com;

“The Man who Deciphered Linear B: Michael Ventris” by W. Andrew Robinson (2002) Amazon.com;

“Introduction to Attic Greek” by Donald J. Mastronarde Amazon.com;

“Greek: An Intensive Course” by Hardy Hansen and Gerald M. Quinn Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Ancient Greek: A Literary Approach” by Cecelia Eaton Luschnig and Deborah Mitchell (2007) Amazon.com;

“Complete Ancient Greek: A Comprehensive Guide to Reading and Understanding Ancient Greek, with Original Texts” by Gavin Betts and Alan Henry (2012) Amazon.com;

“Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction” by Benjamin W. Fortson IV Amazon.com;

“A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language” by Egbert J. Bakker Amazon.com;

“Forty-Six Stories in Classical Greek (Ancient Greek and English Edition)” by Anne H. Groton, James M. May Amazon.com;

Minoan Language

Minoans were the first Europeans to use writing. Their written language was only deciphered in the late 1990s. Known as Linear A, it contains 45 "letters" and is categorized as an ancient form of Greek. The few scraps of Minoan text that have been translated are mainly records of trade, inventories of military equipment, and lists of harvests of wheat and olives. Linear A clay tablets, dated between 1900 and 1700 B.C., were found at Knossos. They were found along with tablets with Minoan hieroglyphics, Linear B, and a still undeciphered Cretan script dated to 2000-1700 B.C.

The Phaistos Disk, found in the ruins of the 3700-year-old B.C. palace of Phaistis, is the earliest know example of printing. The six-inch, baked-clay disk contains 241 pictorial designs comprised of 45 different letters arranged in a spiral formation. The symbols were placed on the disk with a set of punches, one for each symbol, using the same concept as movable type.

The ancient Mycenaeans had a written language in 1200 B.C., called Linear B, that was discovered on clay tablets at Mycenaean and Minoan sites. Tablets found in 1939 at Pylos by American archaeologist Carl Blegen and deciphered in 1940 by an eighteen-year-old young Englishman named Michael Ventris, who revealed his discovery in a 1952 BBC interview and also revealed that the language was a precursor of Greek and the was oldest written Indo-European language known. See Below

See Separate Article: MINOAN WRITING: LANGUAGES. HIEROGLYPHICS, LINEAR A europe.factsanddetails.com

Linear B

The ancient Mycenaeans had a written language in 1200 B.C., called Linear B, that was discovered on clay tablets at Mycenaean and Minoan sites. Tablets found in 1939 at Pylos by American archaeologist Carl Blegen and deciphered in 1940 by an eighteen-year-old young Englishman named Michael Ventris, who revealed his discovery in a 1952 BBC interview and also revealed that the language was a precursor of Greek and the was oldest written Indo-European language known.

These where startling revelations when one considers that no one had any idea what language the Mycenaeans spoke, that written Greek didn't reappear until 400 years later in the 5th century B.C. and that the Greek alphabet and the Mycenaean symbols looked as different from one another as Chinese and English.μ

Blegen found 1,200 clay tablets, which had been preserved in a palace fire in 1200 B.C. He determined that Linear B there was used primarily to record palace inventories and administrative records of thing like olives, wine, chariot wheels, tripods, sheep, oxen, wheat, barely, spices, plots of land, chariots, slaves, horses and taxes to be collected. So far no references to the Trojan War or anyone mentioned in the “ Iliad” have been found in Linear B.

See Separate Article: MYCENAEAN CULTURE AND LIFE: SOCIETY, ART, LINEAR B europe.factsanddetails.com

Development of Written Greek

Written Greek first appeared around the 9th century B.C. The oldest example is an inscription on a vase, dated to the 8th century B.C., given out as a trophy. It reads: “Whoever of the dancers makes merry most gracefully, let him receive this.”

Early Greek writing resembled Phoenician. Anyone who could read ancient Phoenician could also read Greek. But over time the Greek alphabet changed considerably. One of the first major changes was switching the direction of writing from right to left to the opposite direction, left to right,. Phoenician writing was read from right to left like modern Arabic, but the opposite direction of English. In the early years of Greek culture, writing appeared in all different directions — right to left, left to right, up and down — with left to right finally prevailing.

Greek was written only in capital letters and had no punctuation. There were no paragraphs, There wasn’t even spaces between words. These things were introduced in age of Charlemagne. Even so ancient Greek writing is similar enough to modern Greek that modern Greek school children can read the original texts of Aristotle. The ancient Greeks could also create massive compound words like German (see Aristophanes)

Pylos Linear B tablet

Development of the Greek Alphabet

The Greeks borrowed 19 letters from the Phoenician alphabet, dropped three letters and changed two. The Phoenician A for “aeleph” became the Greek alpha. The Phoenicians B for “beth” became beta and D for “daleth” became delta.

The most radical and innovative change made by the Greeks was the addition of vowels. Phoenician writing consisted syllabic sounds beginning with a consonant and ending with a vowel. The Greeks added five vowels similar to our "A," "E," "I," "O," and "U."

Under the Phoenician system a two syllable word like drama written could have at least nine different pronunciations — 1) drama, 2) dramu, 3) drami, 4) drima, 5) drimu, 6) drimi, 7) druma, 8) drumu, 9) drumi — because the vowels sounds were not specified. Most people who could read could recognize which word was meant and which vowel sounds were present by the signs that were given. Even so there was lots of potential confusion. With the addition of vowels these confusions were cleared up.

Greek writing was eventually passed on to 1) the Etruscans who passed their writing on to the Romans and to the 3) Copts in Egypt, who replaced hieroglyphics

Ancient Greek Alphabet and the Phoenician Alphabet

The word alphabet comes from the first two Greek letters “alpha” and “ beta” . The Phoenician alphabet was being used in Greece around 800 B.C. or earlier. The Greeks attributed the introduction of the alphabet to Cadmus, the son of Tyrian king and the sister of the goddess Europe.

The Phoenician alphabet provided the basis for the Greek alphabet which gave birth to the Latin alphabet which beget the modern alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each for sound rather than a word or phrase. It provided the basis for the Hebrew and Arabic alphabet as well as the Greek alphabet which gave birth to the Latin alphabet which beget the modern alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet is the ancestor of all European and Middle Eastern alphabets as well as ones in India, Southeast Asia, Ethiopia and Korea. The English alphabet evolved from the Latin, Roman, Greek and ultimately the Phoenician alphabets. The letter "O" has not changed since it was adopted into the Phoenician alphabet in 1300 B.C.

Phoenician writing was read from right to left like Hebrew and Arab, but the opposite direction of English. The major difference between the 22-letter Phoenician alphabet and the one we use today is that the Phoenician alphabet had no vowels. Its genius was its simplicity.

_4th_Century.jpg)

Magic Pella leaded tablet (katadesmos) 4th Century

Under the Phoenician system a two syllable word like drama written could have at least nine different pronunciations — 1) drama, 2) dramu, 3) drami, 4) drima, 5) drimu, 6) drimi, 7) druma, 8) drumu, 9) drumi — because the vowels sounds were not specified. Most people who could read could recognize which word was meant and which vowel sounds were present by the signs that were given. Even so there was lots of potential for confusion. The Greeks introduced vowels, which cleared up the confusion.

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN ALPHABET AND OTHER EARLY ALPHABETS factsanddetails.com; WORLD’S OLDEST ALPHABETS AND ALPHABETIC WRITTEN LANGUAGES africame.factsanddetails.com ; CANAANITE LANGUAGE AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com ; UGARIT, ITS EARLY ALPHABET AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Writing, Reading and Dictionaries

Ancient Greece was one of the first civilizations to widely use writing as a form of literary and personal expression. For the Mesopotamians and Egyptians writing was used mainly to make records and write down incantations for the dead. The Greeks, by contrast wrote dramas, histories and philosophical and scientific pieces. Even so most people were illiterate and writing was seen mainly as something that helped the memory and aided the spoken word. From what can be ascertained people read aloud rather than silently to themselves.

Aristotle described writing as a means of expressing "affections of the soul." Plato wrote "trust to the external characters and not remember of themselves...They will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing."

Expressions and idioms in ancient Greek went out of date just as quickly as the "cat's pajamas" and the "bees knees" in modern times. The first dictionary was a book of difficult words and expressions from Homer's texts written by Philitas. His student Zenodotus wrote a similar work called “Difficult Words” which made the great innovation of putting the words in alphabetical order. Similar dictionaries included “ Words” by Aristophanes of Byzantium and “ Words of Tragedy” and “ Art of Grammar” by Didymus, a diligent scholar who earned his nickname "Bronze-Guts" for his compilation of at least 3,500 works.

Book: “The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms” by Andrew Robinson

Greek and Latin Shorthand

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Unlike the forms of shorthand that dominated 20th-century Europe and America, however, ancient Greek and Latin shorthand was not always standardized and was uncompromisingly difficult to learn. A second-century contract from Egypt tells us that it took two years for a literate enslaved child to become proficient in Greek shorthand. The curriculum began with the student memorizing a basic set of signs vowels, syllables, word endings, and phrases before progressing to a more complicated system of compound signs. In this second step a single sign was modified by a dot or dash to augment its meaning. With only a few exceptions, these symbols were in no way pictographic, so you couldn’t guess what they meant just by looking at them. This made it useful for military communications and espionage: Both Julius Caesar and the Jewish freedom fighters who led the mid-second-century Bar Kochba revolt used it to send messages. [Source Candida Moss, Daily Beast, November 4, 2022]

Those who learned ancient shorthand were aided by something called the “commentary,” a set of sentences that served as mnemonic devices for the student. A copy of this commentary was published by Sofía Torallas Tovar and Klass Worp in the important volume To the Origins of Greek Stenography. It has helped scholars decipher more complex signs and understand how it was learned. “At the conclusion of this process,” said Baumann, “the student would have learned a system of over 800 signs alongside what is essentially a gigantic lookup table of over 4,000 words and phrases.”

In my own work I have argued that, to the best of our knowledge, only those who went through this arduous process — that is enslaved and formerly enslaved workers — could actually read it. To the untrained eye it resembles squiggles or chicken scratch. Given the transformational nature of translating the spoken word first into symbols and subsequently into ancient Greek (or Latin) literacy seems important.

To complicate the matter even more for modern scholars, people modified and personalized their shorthand systems. So, while a child might have learned a standard form as part of their education, they quickly modified it so that it worked for them. The marginalia in a fragment of Plato discussed by Kathleen McNamee, for example, uses a somewhat modified system. Those who worked in bureaucracy needed legal terms and measurements and those who assisted doctors needed a lot of signs for ailments and body parts. While we have largely deciphered Greek shorthand, we still have to be attentive to it. Dr. Jeremiah Coogan told me that it is highly contextual and emerges out of the practical contexts of workshops, bureaucratic spaces, and households.

The problem, Baumann told me, is that scholars haven’t been that interested in shorthand and, thus, haven’t been fully or accurately noting its presence. When an editor just notes that there were “shorthand marks” in a particular ancient text this doesn’t tell us even how many there were much less what they were. Sometimes editors of manuscripts describe it not as shorthand, but as an “unidentified script.” If an entire text was written in shorthand, it might have been misidentified at some point in its study. And, in some cases, editors might not have registered it at all. The lack of editorial consistency makes it difficult to get a sense of how much untranslated shorthand there even is. Short of going back and reviewing the hundreds of thousands of papyrological fragments sat in university libraries, museums, and private collections we can’t really be sure what is out there.

mosaic with Greek writing

Papyrus and Vellum

Unlike the Mesopotamians who wrote on clay tablets, the Egyptians wrote on papyrus, a brittle paper-like material made from reeds of Nile sedge (a grass-like plant), which were moistened, pounded, smoothed, dried, and pressed woven together like a mat. The word paper is derived from papyrus. Strong enough to endure for millennia and be discovered by archaeologists, papyrus is thicker and heavier than modern paper but good quality and good for writing. Ostraca was a kind of papyrus made of left over stone chips.

During Egyptian times most everything was written on papyrus. When dried out papyrus naturally curled up which is why most literary works were in the form of scrolls The Egyptian learned to make papyrus by 3000 B.C. or earlier. A blank role of papyrus was found sealed in a tomb, perhaps as old as 3200 B.C. First papyrus with writing dates to 2500 B.C. Papyrus was widely used until the A.D. 8th century. Thanks to the dry climate some of ancient Egyptian documents written on papyrus survive today.

Papyrus is light and strong and ideal for writing on. The ancient Egyptians wrote with reed styluses that were not all that different from quill pens used until the 19th century. Scribes used a palate with a slit for storing styli and separate wells for red and black ink. Black ink was made from lampblack and water. The Egyptians built papyrus libraries in 3200 B.C. Some papyrus rolls were 133 feet long.

During Hellenistic times, papyrus was displaced by parchment and vellum, materials made from bleached, stretched animals hide. King Eumenes II (197-159 B.C.) of Pergamum invented parchment from the cleaned, stretched and smooth skins of sheep or goats after the Egyptians cut off the supply of papyrus. He also invented vellum which is especially fine parchment from the skin of a calf. Both "veal" and "vellum" come “ veel” , the Old French word for calf.

Vellum was very durable. It could be rolled up or creased and made into a book. Vellum was very expensive and finer in quality than normal parchment. Paper was invented in Korea and China before the forth century A.D. but wasn't widely used in Europe until the 14th century, after it was carried westward on the Silk Road.

A book made of vellum was called a codex. Vellum was an important innovation in the making of manuscripts. Picture painted on scroll eventually cracked pealed and flaked off from the process of being rolled up. The flat pages of vellum didn't have this problem.

The Greeks used stylus pens made from pointed reeds or stalks. They were not all that much different from quill pens used through the 19th century. Ink was made from a mix of lampblack, gum and water.

See Separate Article: PAPYRUS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MAKING IT AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST PAPYRI AND BOOK europe.factsanddetails.com

Derveni Papyrus with Greek writing

Herculaneum Scrolls

Jana Louise Smit wrote in Listverse,: “When Mount Vesuvius famously wiped out Pompeii in A.D. 79, it also destroyed the neighboring city of Herculaneum. Excavations in 1752 uncovered the latter’s library. Most of the 1,800 scrolls were so badly burned by the eruption they were no more than unreadable carbonized lumps. More than two centuries later, archaeologists used X-rays to read the parchments too fragile to unroll. They managed to pick up Greek letters and phrases, but reading the more damaged scrolls remains an ongoing effort. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, May 15, 2016]

“While the Herculaneum papyri...remain the only complete library ever recovered from ancient times. Some could be opened manually, and they revealed a philosophical treasure—lost prose and poems by the famous Greek philosopher Epicurus. There are even texts that were completely unknown to philosophical scholars.

“Not only does this allow researchers to gain a deeper understanding of ancient Greek and Latin works, but it also adjusts what we know about the history of ink. When scientists analyzed the scroll fragments, they found that the ink contained a high amount of lead. Metallic inks were thought to have been introduced around A.D. 420 for Greek and Roman manuscripts, but the Herculaneum scrolls predate that notion by a couple of centuries.”

See Separate Article: HERCULANEUM SCROLLS europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024