Home | Category: Minoans and Mycenaeans

MYCENAEN, TROJANS AND THE ILIAD

The Mycenaens are regarded as the first Greeks. They perhaps engaged in the the Trojan Wars and inspired the "The Iliad" and "The Odyssey." Their culture abruptly declined around 1200 B.C., marking the start of a Dark Ages in Greece.

According to Associated Press: "Mycenae flourished from the mid-14th to the 12th century B.C. and was one of Greece's most significant late bronze age centers. Its rulers are among the key figures of Greek myth, caught in a vicious cycle of parricide, incest and dynastic strife. The most famous of all, Agamemnon, led the Greek army that besieged and sacked Troy, according to Homer's epics. It is not clear to what extent the myths were inspired by memories of historic events."

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: The age of Homer was an age of heroes — Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae, Odysseus, the king of Ithaca, and Nestor, the king of Pylos, among others — whose deeds are chronicled in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Many archaeologists believe that Homer’s tales, despite being composed 500 or more years after the Late Bronze Age events they describe, had roots in a real past. “There’s always a kernel of truth to stories handed down from generation to generation,” says archaeologist Jack Davis. Whether these men were real people is unknown. But the culture they belonged to, which dominated Bronze Age Greece from around 1600 until 1200 B.C. — known as Mycenaean since it was given that name by nineteenth-century scholars — was certainly the model for the poems’ dimly remembered heroes from the deep past. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

Over the past century, archaeologists and linguists have largely focused their studies on the Mycenaeans’ place in the early development of later classical Greek civilization. Excavations at Pylos, and at sites all across mainland Greece, have provided a great deal of evidence of the Mycenaeans in their prime. This research has revealed that at their peak they were tied into a world that encompassed most of the eastern Mediterranean, including ancient Egypt, the city-states of the Near East, and the islands of the Mediterranean. One such link, though, stands out as perhaps the most important: a deep connection to the island of Crete, which, in the Late Bronze Age, was inhabited by members of a culture scholars call Minoan after the legendary King Minos, a culture very different from that found on the mainland.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MYCENAEANS (1650 AND 1200 B.C.): HISTORY, STATES, COLLAPSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN SITES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN RELIGION: BEEHIVE TOMBS AND MAYBE HUMAN SACRIFICES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN MILITARY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ILIAD: PLOT, CHARACTERS, BATTLES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MYCENAEAN ARCHAEOLOGY: GOLDEN MASKS AND THE GRIFFIN WARRIOR europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mycenaean World” by John Chadwick (1976) Amazon.com;

“Women in Mycenaean Greece: The Linear B Tablets from Pylos and Knossos” by Barbara A. Olsen (2014) Amazon.com;

“Minoans and Mycenaeans: Flavours of Their Time” by Yannis Tzedakis and Holley Martlew (1999) Amazon.com;

“Minoan and Mycenaean Art” by Reynold Higgins (1967) Amazon.com;

“The Decipherment of Linear B” by John Chadwick (1958) Amazon.com;

“The Man who Deciphered Linear B: Michael Ventris” by W. Andrew Robinson (2002) Amazon.com;

“Aegean Linear Script(s): Rethinking the Relationship Between Linear A and Linear B” by Ester Salgarella (2020) (Cambridge Classical Studies) by Ester Salgarella Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World” by Y. Duhoux, Anna Murpurgo Davies(2007) Amazon.com;

“Documents in Mycenaean Greek: Three Hundred Selected Tablets from Knossos, Pylos, and Mycenae” by Michael Ventris (1956) Amazon.com;

“The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek: Volume 1, Introductory Essays” by John Killen (2024) Amazon.com;

“The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek: Volume 2, Selected Tablets and Endmatter” by John Killen (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans” by Rodney Castleden (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans” by Louise Schofield (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Mycenaeans” by William Taylour (1964) Amazon.com;

Mycenaean Leadership and Society

Most scholars today, believe there was no single ruler of the Mycenaean world-or even a unified Mycenaean realm over which one ruler ruled. The available evidence suggests that Bronze Age Greece was divided into several different political centers, each with its own ruler, or wanax. The wanax of Mycenae could have been one of the most powerful of these rulers, but his authority likely did not extend across the whole of Greece. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2023]

Around 1450 B.C., Greece was divided into a series of kingdoms on the Greek mainland, the most important centered at Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos and Thebes. In the subsequent decades, the Mycenaeans began to expand throughout the Aegean, filling the niche previously filled by Neopalatial Minoan society. [Source Wikipedia]

The state of Mycenae was ruled by a king. Other states such as Pylos had their leaders. Under the king of Mycenae was a “leader of the people,” perhaps a military leader. There were landowners, nobles, tenant farmers, servants, slaves and people that engaged in a large number of trades and professions.

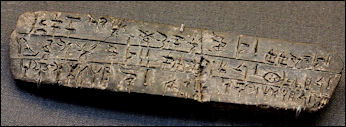

Linear B

The ancient Mycenaeans had a written language in 1200 B.C., called Linear B, that was discovered on clay tablets at Mycenaean and Minoan sites. Tablets found in 1939 at Pylos by American archaeologist Carl Blegen and deciphered in 1940 by an eighteen-year-old young Englishman named Michael Ventris, who revealed his discovery in a 1952 BBC interview and also revealed that the language was a precursor of Greek and the was oldest written Indo-European language known.

Linear B script clay tablet Linear B is an early form of ancient Greek writing used by the palaces during the Mycenaean era of Greece (1600-1100 B.C.). Nicholas Wade wrote in the New York Times: “Linear B tablets were preserved in the fiery destruction of palaces when the soft clay on which they were written was baked into permanent form. Caches of tablets have been found in Knossos, the main palace of Crete, and in Pylos and other mainland palaces. Linear B, a script in which each symbol stands for a syllable, was later succeeded by the familiar Greek alphabet in which each symbol represents a single vowel or consonant.” [Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, October 26, 2015]

These where startling revelations when one considers that no one had any idea what language the Mycenaeans spoke, that written Greek didn't reappear until 400 years later in the 5th century B.C. and that the Greek alphabet and the Mycenaean symbols looked as different from one another as Chinese and English. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Blegen found 1,200 clay tablets, which had been preserved in a palace fire in 1200 B.C. He determined that Linear B there was used primarily to record palace inventories and administrative records of thing like olives, wine, chariot wheels, tripods, sheep, oxen, wheat, barely, spices, plots of land, chariots, slaves, horses and taxes to be collected. So far no references to the Trojan War or anyone mentioned in the “ Iliad” have been found in Linear B.

Significance of Linear B

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: When clay tablets found at Pylos and other sites, including Mycenae, were deciphered in the 1950s, the narrative that the Minoans and Mycenaeans were closely related was pushed in a completely different direction. Linear B resembled Crete’s Linear A, but recorded an entirely different language — Mycenaean Greek. It became clear that it was related to the language of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and, more distantly, to the other Indo-European languages, from Sanskrit to English. Scholars today can peruse the bureaucratic records left behind in the Palace of Nestor, while Linear A and the language it records remain an impenetrable mystery. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

Mycenaean Woman “The discovery and decipherment of Linear B led scholars to rethink the relationship between Mycenae and Crete. Not only were the Mycenaeans the true forebears of the ancient Greeks, scholars argued, they were indiscriminate thieves who imported or copied Minoan objets d’art without understanding their meaning or significance. “At the time, most scholars were thinking of hostile takeovers, not cooperative ventures,” says archaeologist Cynthia Shelmerdine of the University of Texas at Austin.

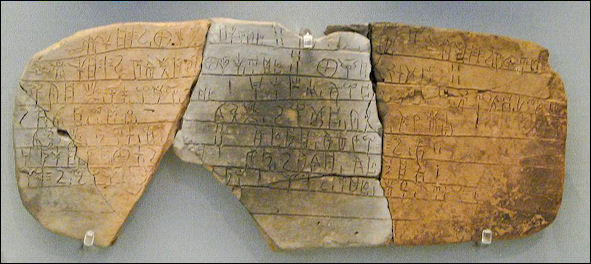

3,500-Year-Old Writing Found in Mainland Greece

In the summer of 2010, a 3,400-year-old tablet with some of the oldest known examples of writing in mainland Europe, was found in an ancient refuse pit in the middle of an olive grove in southwest Greece, near the modern village of Iklaina. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “The tablet seems to be a “page” from a bookkeeper’s note pad. Not meant to be saved as a permanent record, it was not baked in a kiln , but ended up in a refuse dump, where a fire hardened the clay for posterity... Had it not been for some inadvertence, the tablet would almost certainly have disintegrated in the rain in a year or two and scattered with the wind as so much illiterate dust.” [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, April 4, 2011]

Amanda Summer wrote in Odyssey magazine: “The fragment appears to be part of a bookkeeper's ledger; one side is a possible personnel list of male names followed by numbers, and the other preserves the heading for what might have been a list of manufactured products. Why is this two by three inch clay slab so important? The existence of a tablet means that Iklaina had scribes, a product of bureaucracy, suggesting a high level of political organization and the need to keep track of commodities. "According to what we had known until now, this tablet should not have been found here, because all known stratified tablets come from the Mycenaean palaces," Cosmopoulos explains. On top of that, most tablets are dated to ca. 1200 B.C. or the period of the Trojan War, but the Iklaina tablet is dated to 1450 to 1350 B.C. Because tablets were used exclusively for recording transactions and property of the Mycenaean governments, this tablet is the earliest known bureaucratic record on the Greek mainland. The location and date of the tablet suggest that the origins of literacy and political states in Greece were earlier and more widespread than what was thought until now.” [Source: Amanda Summer, Odyssey, September, October 2012]

The discoverers and other specialists in Greek history said the tablet should cast light on the political structure and bureaucratic practices near the beginning of the renowned Mycenaean period, 1600 to 1100 B.C. At its height, the culture supported the splendor of palaces at Mycenae and Pylos and inspired the heroic legend of the Trojan War, immortalized in Homer’s Iliad.

“This is a rare case where archaeology meets ancient texts and Greek myths,” Michael B. Cosmopoulos, director of the excavations, said last week in announcing the discovery. Dr. Cosmopoulos, an archaeologist and professor of Greek studies at the University of Missouri, St. Louis, said the tablet, only 2 inches by 3 inches, was a surprise. Judging by pottery in the dump in which it was found, the tablet dates to sometime from 1490 to 1390 B.C. Scholars said they had little evidence before that clay tablets were made and used to keep state records so early in Mycenaean history.

Elsewhere, the Minoans on the island of Crete were keeping records as early as 1800 B.C. in an enigmatic script that predates the Mycenaean Linear B. The earliest known writing, also presumably for bookkeeping, evolved around 3200 B.C. in the Sumerian city of Uruk, in Mesopotamia. The first Egyptian writing appeared more or less at the same time.

The Missouri team had investigated the Iklaina site for 11 years, and in the last couple of summers examined the extensive evidence of stone walls of what may have been a palace at a district capital. Some walls are decorated with frescoes showing ladies of the court and ships with dolphins cavorting in water. There are also remains of a drainage and sewer system far ahead of its time.

Iklaina tablet

Archaeologists are only beginning to consider the implications of the discovery. It suggests that political states in ancient Greece originated at least a century and a half earlier than had been documented. Iklaina may have started small and been conquered and annexed by one of the expanding powers, like Pylos, in the same region. Dr. Cosmopoulos suggested the Iklaina palace may have been a district administrative center subject to one of the main capitals: “a two-tiered government, or a sort of quasi-federal system,” he called it.

3,500-Year-Old Tablet and Early Greek Bureaucratic Practices

John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times, “Previous excavations had yielded clay writing tablets from 1200 B.C., close to the approximate time of the supposed Trojan War, and some references to Iklaina as an administrative center associated with Pylos. Dr. Cosmopoulos said in an interview that the new findings appeared to show that some 200 years earlier this may have been the seat of an independent chiefdom that had already achieved a degree of literacy and political organization. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, April 4, 2011]

On one side, the tablet has one readable word, a verb meaning to prepare to manufacture. Along the broken edges are other characters, but not enough for scholars to make out the word or words. On the reverse side, the tablet gives a list of men’s names alongside numbers. Cynthia Shelmerdine at the University of Texas, Austin, was the first to read the writing and assess its importance.

“The fact that we have a tablet like this means that this government had scribes, and scribes are a product of bureaucracy,” Dr. Cosmopoulos said. “And this suggests some degree of political complexity and a growing need to keep track of commodities, property and taxes, all earlier than we once thought.”

Donald C. Haggis, an archaeologist and classics professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said the tablet discovery was “really exciting and important because we don’t know much of the dynamics of these palace sites and the early phases of state formation in Greece.” Dr. Haggis, who was familiar with the research but not a member of the team, said that nearly all that had been known of the dynamics of these government centers came from excavations in the final stages of the Mycenaean period. Now the tablet, he said, “tells us this place had an administrative function at an early stage” and the architecture of the palace “reflects authority” and “looks like a place for ritual, communal dining and production of crafts.”

Linear tablet of Pylos

Griffin Warrior Artifacts

In 2015, archaeologists digging at Pylos, announced they had discovered the rich grave of a soldier that they dubbed the “Griffin Warrior” after images of griffins found on artifacts found in the grave. The grave was discovered by Jack L. Davis and Sharon R. Stocker, a husband-and-wife team at the University of Cincinnati who have been excavating at Pylos for 25 years. [Source: Nicholas Wade, New York Times, October 26, 2015]

Ángel Carlos Pérez Aguayo wrote in National Geographic History: Around 1,400 objects have been recovered from the grave. Many are being restored for display in the nearby Chora Archaeological Museum. Hundreds of gems including amethyst, jasper, amber, carnelian, and agate have been recovered. Especially intriguing is a braided necklace that shows signs of damage and repair in antiquity. A faience bead hangs from the necklace of Egyptian manufacture. According to archaeologists, it may have been a spoil of war torn from its owner’s neck and subsequently mended before being buried with the warrior. Six silver cups and several bronze containers for dining purposes were also found, as well as several ivory combs and a mirror. [Source Ángel Carlos Pérez Aguayo, National Geographic History, August 5, 2022]

These exquisite artifacts are more than just beautiful; they are evidence of Mycenaean interaction with another culture, the Minoans. Many of the artifacts are from Crete, a large island some 100 miles south of Pylos, which was home to the Minoan civilization. Among these items are gold signet rings bearing engravings of ritual scenes that are typically Cretan. Around 50 gems in the burial are also ornamented with common Minoan motifs, such as bulls. More than 50 sealstones, including a carnelian one featuring three bulls, were found in the Griffin Warrior’s tomb.

Among the artifacts are: 1) a bronze sword with a gold-embroidered pommel; 2) the Pylos Combat Agate, with an image of the flowing-haired victorious warrior holding an identical type of sword; 3) A gold ring depicting a goddess descending from rocky peaks, flanked by two birds alighting on the peaks; and 4) a gold ring, with two female figures, the larger of whom, likely a goddess, sits on a throne and holds a stemmed object thought to be a mirror. A bird with a long, swallow-like tail perches on the throne, and the wavy lines at the top appear to represent the heavens. cord. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

There is also a 5) A heavily corroded bronze disk with gold foil decorations (an X-ray of the disk shows a a sun with 16 points) that was likely attached to the warrior’s armor. 6) A bronze mirror with an ivory handle and an ornate ivory comb are among the artifacts from the grave suggesting that the warrior was a man of high status and was concerned with his appearance.

Perhaps the most exceptional piece from the tomb, the so-called Combat Agate reveals the intertwined influences of these ancient cultures. It took roughly a year to clean and preserve the stone once it had been removed from the tomb, but the results were nothing short of amazing. It is considered to be one of the most exquisite hard stone carvings from all antiquity. Measuring slightly more than an inch long, this tiny, semi-precious stone features a finely detailed depiction of a heated clash between two warriors. A fallen comrade lies beneath their feet as one soldier is poised to pierce the neck of his opponent.

See Separate Article: MYCENAEAN ARCHAEOLOGY: GOLDEN MASKS AND THE GRIFFIN WARRIOR europe.factsanddetails.com

Insights in Mycenaean Life from Iklaina

Bathtub from the Palace of Nestor

Amanda Summer wrote in Odyssey magazine: “In addition to the imposing Cyclopean building complex, Cosmopoulos has identified a large town sprawling to the north, consisting of multiple small dwellings. Between 1400 and I 350 B.C. the site was destroyed and the new rulers built their settlement directly on top of the old town with a different orientation, in a display of superiority in the establishment of a new authority. Cosmopoulos believes this is evidence the site was annexed at that time by the Palace of Nestor, now a major power in the area. The new construction included a mega ron- a great hall of a Mycenaean house containing a central hearth surrounded by four pillars. It is uncl ear if the megaron was used for administrative purposes, or was simply a wealthy house, but Cosmopoulos hopes further excavation in the area will establish its function. [Source: Amanda Summer, Odyssey, September, October 2012 ]

“The ancient inhabitants were advanced enough to have running water, evidenced by an extensive drainage system and clay pipes, originating from a series of rooms that were used as industrial installations.Large deposits of flaxseed were uncovered in those rooms, so it's probable that flax production was a major industry at the site. Ancient Iklaina may have also supported metalworking, as the Linear B tablets from Pylas mention a-pu2 as a metallurgical center. At least nine smiths and up to 225 workmen may have worked at the site, some of whom received bronze from the palace, and numerous metal objects such as bronze nails, saws and rings have been found, as well as a unique head of a bronze male figurine.

“A significant building, aligned along one side with an upright rectangular stone known as a "stele", was uncovered in the final weeks of the 20 II season. At some Bronze Age sites such markers indicate a sacred space, but in this case, Cosmopoulos believes the building may have been unfinished and the post was a construction marker. "We've never seen anything like it," Cosmopoulos says. The team has uncovered no artifacts in the interior of the structure, but Cosmopoulos believes its size and formal construction may indicate it was used for a special function. The 20 II season also marked the discovery of what may be the first known Mycenaean open-air shrine. This pit, containing evidence of fire along with plaster offering tables, fragments of frescoes, a folded lead sheet, numerous burned bones from very young animals and scores of drinking vessels, opens up new avenues for the study of Mycenaean religion. In 2009 workers excavated the skeleton of a young female, about twelve, who had been buried alongside a wall near the Cyclopean.terrace. Why she was buried alone is uncertain, but Cosmopoulos believes there are more burials to be found nearby.”

Mycenaeans Used Grills and Non-Stick Pans To Make Souvlaki and Bread

In 2014, researchers reported that ancient Mycenaeans used ceramic portable grill pits to make souvlaki and non-stick pans and griddel made of clay to make bread more than 3,000 years ago, It wasn’t clear how these types of pans were used, said Julie Hruby of Dartmouth College, presenting her research at the Archaeological Institute of America’s annual meeting. “We don’t have any recipes,” she told LiveScience. “What we do have are tablets that talk about provisions for feasts, so we have some idea of what the ingredients might have been, but in terms of understanding how people cooked, the cooking pots are really our best bet.” [Source:Megan Gannon, Live Science, January 08, 2014 ~~]

boar tusk helmet

Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science: “The souvlaki trays were rectangular ceramic pans that sat underneath skewers of meat. Scientists weren’t sure whether these trays would have been placed directly over a fire, catching fat drippings from the meat, or if the pans would have held hot coals like a portable barbeque pit. The round griddles, meanwhile, had one smooth side and one side covered with tiny holes, and archaeologists have debated which side would have been facing up during cooking. To solve these culinary mysteries, Hruby and ceramicist Connie Podleski, of the Oregon College of Art and Craft, mixed American clays to mimic Mycenaean clay and created two griddles and two souvlaki trays in the ancient style. With their replica coarsewares, they tried to cook meat and bread. ~~

“Hruby and Podleski found that the souvlaki trays were too thick to transfer heat when placed over a fire pit, resulting in a pretty raw meal; placing the coals inside the tray was a much more effective cooking method. “We should probably envision these as portable cooking devices — perhaps used during Mycenaean picnics,” Hruby said. As for the griddles, bread was more likely to stick when it was cooked on the smooth side of the pan. The holes, however, seemed to be an ancient non-sticking technology, ensuring that oil spread quite evenly over the griddle. ~~

“Lowly cooking pots were often overlooked, or even thrown out, during early excavations at Mycenaean sites in the 20th century, but researchers are starting to pay more attention to these vessels to glean a full picture of ancient lifestyles. As for who was using the souvlaki trays and griddles, Hruby says it was likely chefs cooking for the Mycenaean ruling class.“They’re coming from elite structures, but I doubt very much that the elites were doing their own cooking,” Hruby told LiveScience. “There are cooks mentioned in the Linear B [a Mycenaean syllabic script] record who have that as a profession — that’s their job — so we should envision professional cooks using these.” ~~

Mycenaean Art and Architecture

Mycenaean ceramics, painted with distinctive shiny red and black images, was crafted into storage jars and ceremonial vessels. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the Mycenaean period, the Greek mainland enjoyed an era of prosperity centered in such strongholds as Mycenae, Tiryns, Thebes, and Athens. Local workshops produced utilitarian objects of pottery and bronze, as well as luxury items, such as carved gems, jewelry, vases in precious metals, and glass ornaments. Contact with Minoan Crete played a decisive role in the shaping and development of Mycenaean culture, especially in the arts. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

Architecturally the Mycenaeans were known for their fortified cities which were surrounded by walls with such large stone the some Greeks thought giants like the Cyclops were needed to build them. Mycenaean palaces were built around great central halls called megarons. Strangely one Mycenaean city — Pylos — had virtually no fortifications Mycenae had no temples, the palaces has modest shrines. The Mycenaeans built roads graded for wagons and chariots.

The Mycenaeans built large palaces with specialized rooms for food storage, repairing chariots, making ceramics, keeping archives and writing records on stone tablets. Many of the walls were plastered and some were decorated with frescoes.

Oldest Wall Painting in Greece

Among the finds at Nestor’s Palace in the Mycenaean city of Pylos, Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine, are remnants from what are likely the oldest wall paintings ever found on the Greek mainland. The fragments, which measure between roughly one and eight centimeters across and may date as far back as the 17th century B.C., were found beneath the ruins of Nestor’s Palace. The researchers speculate that the paintings once covered the walls of mansion houses on the site before the palace was built. Presumably, the griffin warrior lived in one of those mansions. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2017]

“Moreover, small sections of pieced-together fragments indicate that many of the paintings were Minoan in character, showing nature scenes, flowering papyri and at least one miniature flying duck, according to Emily Egan, an expert in eastern Mediterranean art at the University of Maryland at College Park who worked on the excavations and is helping to interpret the finds. That suggests, she says, a “very strong connection with Crete.”

“Together with grave goods that have been found, the wall paintings present a remarkable case that the first wave of Mycenaean elite embraced Minoan culture, from its religious symbols to its domestic décor. “At the very beginning, the people who are going to become the Mycenaean kings, the Homeric kings, are sophisticated, powerful, rich and aware of something beyond the world that they are emerging from,” says Shelmerdine.

In their view, the arrangement of objects in the grave provides the first real evidence that the mainland elite were experts in Minoan ideas and customs, who understood very well the symbolic meaning of the products they acquired. “The grave shows these are not just knuckle-scraping, Neanderthal Mycenaeans who were completely bowled over by the very existence of Minoan culture,” says John Bennet, of the British School at Athens. “They know what these objects are.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum except Iklaina and Iklaina tablet, Iklaina Archeological Project, teenager skeleton from The Guardian and skull from Archaeology wiki

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024