Home | Category: Ethnic Groups and Regions

CELTS

The Celts were a group of related tribes, linked by language, religion and culture, that gave rise to the first civilization north of the Alps. They emerged as a distinct people around the 8th century B.C. and were known for their fearlessness in battle. Pronouncing Celts with a hard "C" or soft "C" are both okay. American archeologist Brad Bartel called the Celts "the most important and wide-ranging of all European Iron Age people." English speakers tend to say KELTS. The French say SELTS. The Italian say CHELTS. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1977]

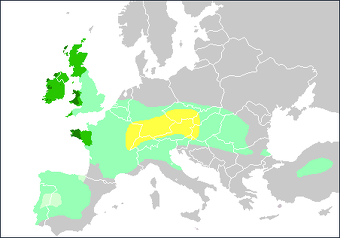

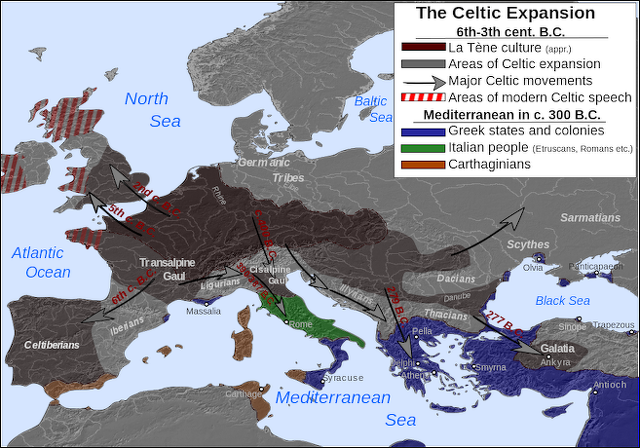

The origin of the Celts remains a mystery. Some scholars believe they originated in the steppes beyond the Caspian Sea. They first appeared in central Europe east of the Rhine in the seventh century B.C. and inhabited much of northeast France, southwest Germany by 500 B.C. They crossed the Alps and expanded into the Balkans, north Italy and France around the third century B.C. and later they reached the British isles. They occupied most of western Europe by 300 B.C.

The Celts were a warlike and artistic people with a highly developed society. They used iron weapon and horses. Celts in Bulgaria were producing bronze from copper and imported iron 3,500 years ago, about same time that the Hittites in Asia Minor, one of the first producers or iron, began producing the metal. Individual Celtic tribes were fiercely independent. They never coalesced into a great empire like Rome or Greece. Celts in different regions shared a similar culture and spoke similar languages.

Most of the great Barbarian tribes of the post-Roman period, many of who were involved in the fall of Rome, were either Germanic (Teutonic) or Celts. Druids and Gauls were Celts. Goths, Visigoths and Vandals were Germanic Tribes. The Iberians occupied Spain and intermingled with Celts. The Huns came from Central Asia.

On Celtic customs, Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (A.D., c. 20): “In Gaul, the heads of enemies of high repute they used to embalm in cedar oil and exhibit to strangers, and they would not deign to give them back ever for a ransom of an equal weight of gold. But the Romans put a stop to these customs, as well as to all those connected with the sacrifices and divinations that are opposed to our usages. They used to strike a human being, whom they had devoted to death, in the back with a sword, and then divine from his death-struggle. But they would not sacrifice without the Druids. We are told of still other kinds of human sacrifices; for example, they would shoot victims to death with arrows, or impale them in the temples, or having devised a colossus of straw and wood, throw into the colossus cattle and wild animals of all sorts and human beings, and make a burnt-offering of the whole thing.” [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Germanic Warriors” by Michael P. Speidel (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples” by H. Wolfram (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Celts” (Penguin History) by Nora Chadwick (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Celts” by Barry Cunliffe Amazon.com;

“The Celts” by Alice Roberts (2017) Amazon.com;

“Romans on the Rhine: Archaeology in Germany”, 170 illustrations by Paul MacKendrick (1970) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Campaigns in Germany: 12 BC to 90 AD” by John Plant (2022)

Amazon.com;

“Germania” by Tacitus Amazon.com;

“Getica: The Origins and Deeds of the Goths” by Jordanes Jordanis, Dean Marais, et al. | (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Pfahlgraben: An Essay Towards A Description Of The Barrier Of The Roman Empire Between The Danube And The Rhine” by Thomas Hodgkin (2023) Amazon.com;

“Romans and Barbarians: Four Views from the Empire's Edge” by Derek Williams (1968) Amazon.com;

“Barbarians in the Greek and Roman World” by Erik Jensen (2018) “Empires and Barbarians” by Peter Heather Amazon.com;

href="https://amzn.to/42q79z1"> Amazon.com;

“The Roman Barbarian Wars I: The Era of Roman Conquest ” by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Barbarian Wars II: Tiberius to Trajan” by Ludwig Heinrich Dyck (2025) Amazon.com;

“Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376 - 568" by Guy Halsall (2008) Amazon.com;

“Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity” by Ralph W. Mathisen and Danuta Shanzer (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Enemies of Rome: The Barbarian Rebellion Against the Roman Empire” by Stephen Kershaw (2021) Amazom.com

“Rebels Against Rome: 400 Years of Rebellions Against the Rule of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins ((2023) Amazon.com;

“Atlas of the Roman World” by (1981) Amazon.com

“Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation” by Rebecca F. Kennedy , C. Sydnor Roy, et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

“Cultural Identity in the Roman Empire” by Joanne Berry, Ray Laurence (2002) Amazon.com;

“Law in the Roman Provinces (Oxford Studies in Roman Society & Law)

by Kimberley Czajkowski, Benedikt Eckhardt, et al. (2020) Amazon.com;

"Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World"

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“Migration and Mobility in the Early Roman Empire” by Luuk de Ligt and Laurens Ernst Tacoma (2016) Amazon.com;

Historical and Archeological Evidence of Celts

Celts

The Celts had a written language but they left behind very few written records. Most of what we know about the ancient Celts has been ascertained from descriptions of them by Roman and Greek writers and historians and artifacts unearthed at burial sites and archeological excavations. Most of what was written about the Celts by the Greeks and Romans had a negative spin because the Celts were traditional enemies of the Greeks and Romans. The Roman referred to the Celts as "barbarians" and a "scourge." Irish monks are no more reliable. They didn’t want to portray their ancestors as heathens.

The richest Celtic archeological site is a huge cemetery found near Hallstat in Salkammergut, Austria. It contained 2,000 Iron Age graves, filled with sophisticated heavy swords, daggers, axes, caldrons, pottery and jewelry with geometric and animal designs. The discovery became known as the Hallstat culture and was dated to the eight to fifth centuries B.C.

In 1734 an ancient Celt was found in a salt mine by miners. It was believed the man died in an avalanche. The body was so well preserved it was thought to a devil and was disposed of. Nobody knows what happened to the body. The backpack he may have used for carrying salt and his pick, shovel, firebrand and leather cap can all be seen in the museum in Hallstatt Austria.

Le Téne on Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, was one of the most important Celtic settlements. Archeologists found iron weapons and jewelry there. Scholars referred to the people that lived there as the Le Téne culture. Le Téne objects have turned up in Italy, Spain, France, Hungary, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, the Ukraine, giving archeologist their first indication of how widespread the Celts were.

Celts, Europe and Greeks

The Celts are regarded by some scholars as the "first true Europeans". They created the first civilization north of the Alps and are believed to have evolved from tribes that originally lived in Bohemia, Switzerland, Austria, southern Germany and northern France. They were contemporaries of the Mycenaeans in Greece who lived around the time of Trojan War (1200 B.C.) and may have evolved from the Corded Ware Battle Ax People of 2300 B.C. The Celts founded a kingdom of Galatia in Asia Minor that received an Epistle from St. Paul in the New Testament.

At their height in the 3rd century B.C. Celts confronted enemies as far east as Asia Minor and as far west as the British Isles. They ventured to the Iberian Peninsula, to the Baltic, to Poland and Hungary, Scholars believe that Celtic tribes migrated over such a large area for economic and social reasons. They suggest that many of the migrants were men who hoped to claim some land so they could claim a bride.

King Attalus I defeated the Celts in 230 B.C. in what is now western Turkey. To honor the victory, Attalus commissioned a series of sculptures including a sculpture that was copied by the Romans and later called The Dying Gaul.

The Celts were known as the "Caltha" or "Gelatins" to the Greeks and attacked the sacred shrine of Delphi in the 3rd century B.C. (Some sources give date of 279 B.C.). Greek warriors who encountered the Gauls said they "knew how to die, barbarians though they were." Alexander the Great once asked what the Celts feared more than anything else. They said "the sky falling down on their head." Alexander sacked a Celtic city on the Danube before heading off on his march of conquest across Asia.

Goths, Gauls and Franks

Goths

The Goths were one of the main groups that threatened Rome. Originally from Scandinavia, they were the first Teutonic people to be Christianized. They migrated from Sweden across the Baltic Sea, through what is now Russia and the Ukraine to the Black Sea. From there they migrated into the Balkans and divided into two groups the Ostrogoths (East Goths) and Visagoths (West Goths). Before their division the Goths were allowed by the Romans to settle within the borders of the Roman Empire. They rose against the Romans and killed the Roman emperor Valentinian in battle. His successor Theodosius sued for peace.

The Gauls were basically Celts that lived in Gaul (France) as well as in extreme northern Italy and areas in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Many centuries earlier they crossed the Alps from western Europe and pushed back the Etruscans and occupied the plains of the Po; hence this region received the name which it long held, Cisalpine Gaul. They held this territory against the Ligurians on the west and the Veneti on the east; and for a long time were the terror of the Italian people when Rome was a village in the 7th century B.C. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

On the manners and customs of the Gauls and the Germans, Tacitus (A.D. 56–120) wrote: Factions exist in Gaul, not only among all the tribes and in all the smaller communities and subdivisions, but, one may almost say, in separate households: the leaders of the rival factions are those who are popularly regarded as possessing the greatest influence; and accordingly to their arbitrament and judgement belongs the final decision on all questions and political schemes. This custom seems to have been established at a remote period in order that none of the common people might lack protection against the strong; for the rival leaders will not suffer their followers to be oppressed or overreached; otherwise they do not command their respect. The same principle holds good in Gaul regarded in its entirety, the tribes as a whole being divided into two groups.

“Once there was a time when Gauls were more warlike than Germans, actually invading their country and, on account of their dense population and insufficient territory, sending colonies across the Rhine. Thus the most fertile districts of Germany around the Hercynian forest (which, I find, was known by degeneracy name to Eratosthenes and other Greeks, who called it Orcynia), and there settled. To this day the people in question, who enjoy the highest reputation for fair dealing and warlike prowess, continue to occupy this territory. The Germans still live the same life of poverty, privation, and patient endurance as before, and their food and physical training are the same; while the Gauls, from the proximity of the provinces and familiarity with seaborne products, are abundantly supplied with luxuries and articles of daily consumption. Habituated, little by little, to defeat, and beaten in numerous combats, they do not even pretend themselves to be as brave as their neighbours.

The Franks, a federation Teutonic tribes, were another group that were around at the time Rome fell. They arrived from what is now Germany and settled as far as the Somme River around A.D. 250 during a westward drive by Germanic tribes. By the 5th century, the Merovingian Franks had thrown out the Romans, and swept over a large population of mostly Romanized Gauls, Burgundians and Gaohs. Childeric I became leader of the Merovingian Franks in A.D. 458. His son was Clovis, regarded by some as the foudner of France. Other Frank tribes spread as far as Greece.

An argument persists today on whether the French descended from the Germanic Franks from the north or the Romanticized Gauls from the south. The French right has traditionally linked themselves with the Franks while the left has traditionally claimed descent form the Gauls, who were regarded as libertarian and egalitarian without necessarily being Christian. The Franks are mostly closely linked with Christianity and Catholicism.

Germanic Tribes and Celts

Germania

Some scholars believe that the Celts and Germanic tribes were two district groups that have separate histories and originated in different places. Others believe that the Germanic tribes were a subsidiary branch of a dominant Celtic society.

Germanic tribes are usually identified as a completely independent people from the Celts but in fact they are closely related.The distinction between Gauls (Celts) and Germanic tribes can be traced back to Julius Caesar who decided that Gaul region was worth conquering and the Germanic region to north wasn't.

The Romans invaded Britain but didn't invade Ireland or Scotland, which remained Celtic. The Celtic tribes in Gaul mixed with Romans and they in turn mixed with Teutonic tribes invaders that arrived in the A.D. 5th century after the Romans. The Franks and Burgundians which emerged after this period, who give their name to France and Burgundy, were a mixture of Roman, Celtic and Teutonic blood, but they were different enough to remain an ethnic group a apart form the Germanic ethnic groups to the north and east. The Saxons and Angles (Anglo-Saxons) were Germanic tribes that arrived in Britain in the A.D. 5th century and mixed with the Roman and Celtic groups there.

Julius Caesar on the Germans

Frederic Austin Ogg wrote: “This general account of the Germans is drawn from the middle of Book VI of De Bello Gallico. We are not to suppose that Caesar's knowledge of the Germans was in any sense thorough. At no time did he get far into their country, and the people whose manners and customs he had an opportunity to observe were only those who were pressing down upon, and occasionally across, the Rhine boundary — a mere fringe of the great race stretching back to the Baltic. We may be sure that many of the more remote German tribes lived after a fashion quite different from that which Caesar and his legions had an opportunity to observe on the Rhine-Danube frontier. Still, Caesar's account, vague and brief as it is, has an importance that can hardly be exaggerated. These early Germans had no written literature, and but for the descriptions of them left by a few Roman writers, such as Caesar, we should know almost nothing about them. [Source: Frederic Austin Ogg, ed., “A Source Book of Mediaeval History: Documents Illustrative of European Life and Institutions from the German Invasions to the Renaissance,” (New York, 1907, reprinted by Cooper Square Publishers (New York), 1972), pp.20-22]

Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) wrote in “The Gallic Wars” (“De Bello Gallico” c. 51 B.C.): “The customs of the Germans differ widely from those of the Gauls; for neither have they Druids to preside over religious services, nor do they give much attention to sacrifices. They count in the number of their gods those only whom they can see, and by whose favors they are clearly aided; that is to say, the Sun, Vulcan, and the Moon. Of other deities they have never even heard. Their whole life is spent in hunting and in war. From childhood they are trained in labor and hardship.

chained Germanic

“They are not devoted to agriculture, and the greater portion of their food consists of milk, cheese, and flesh. No one owns a particular piece of land, with fixed limits, but each year the magistrates and the chiefs assign to the clans and the bands of kinsmen who have assembled together as much land as they think proper, and in whatever place they desire, and the next year compel them to move to some other place. They give many reasons for this custom---that the people may not lose their zeal for war through habits established by prolonged attention to the cultivation of the soil; that they may not be eager to acquire large possessions, and that the stronger may not drive the weaker from their property; that they may not build too carefully, in order to avoid cold and heat; that the love of money may not spring up, from which arise quarrels and dissensions; and, finally, that the common people may live in contentment, since each person sees that his wealth is kept equal to that of the most powerful.

“It is a matter of the greatest glory to the tribes to lay waste, as widely as possible, the lands bordering their territory, thus making them uninhabitable. They regard it as the best proof of their valor that their neighbors are forced to withdraw from those lands and hardly any one dares set foot there; at the same time they think that they will thus be more secure, since the fear of a sudden invasion is removed. When a tribe is either repelling an invasion or attacking an outside people, magistrates are chosen to lead in the war, and these are given the power of life and death. In times of peace there is no general magistrate, but the chiefs of the districts and cantons render justice among their own people and settle disputes. Robbery, if committed beyond the borders of the tribe, is not regarded as disgraceful, and they say that it is practiced for the sake of training the youth and preventing idleness. When any one of the chiefs has declared in an assembly that he is going to be the leader of an expedition, and that those who wish to follow him should give in their names, they who approve of the undertaking, and of the man, stand up and promise their assistance, and are applauded by the people. Such of these as do not then follow him are looked upon as deserters and traitors, and from that day no one has any faith in them. To mistreat a guest they consider to be a crime. They protect from injury those who have come among them for any purpose whatever, and regard them as sacred. To them the houses of all are open and food is freely supplied.”

Tacitus: Germania

Tacitus (A.D. 56–120) was an important Roman historian. He wrote the most detailed early description of the Germans at the end of the A.D. first century, but this description often says more about Rome and Roman perceptions of the German tribes than it does about Germany itself. Tacitus wrote in “Germania”: The Germans themselves I should regard as aboriginal, and not mixed at all with other races through immigration or intercourse. For, in former times it was not by land but on shipboard that those who sought to emigrate would arrive; and the boundless and, so to speak, hostile ocean beyond us, is seldom entered by a sail from our world. And, beside the perils of rough and unknown seas, who would leave Asia, or Africa for Italy for Germany, with its wild country, its inclement skies, its sullen manners and aspect, unless indeed it were his home?” [Source: Tacitus, The Agricola and Germania, A. J. Church and W. J. Brodribb,trans. London: Macmillan, 1877, pp. 87- 110]

Physical Characteristics. “For my own part, I agree with those who think that the tribes of Germany are free from all taint of intermarriages with foreign nations, and that they appear as a distinct, unmixed race, like none but themselves. Hence, too, the same physical peculiarities throughout so vast a population. All have fierce blue eyes, red hair, huge frames, fit only for a sudden exertion. They are less able to bear laborious work. Heat and thirst they cannot in the least endure; to cold and hunger their climate and their soil inure them.”

Suebian knot of some Germanic tribes

Government. Influence of Women. “They choose their kings by birth, their generals for merit. These kings have not unlimited or arbitrary power, and the generals do more by example than by authority. If they are energetic, if they are conspicuous, if they fight in the front, they lead because they are admired. But to reprimand, to imprison, even to flog, is permitted to the priests alone, and that not as a punishment, or at the general's bidding, but, as it were, by the mandate of the god whom they believe to inspire the warrior. They also carry with them into battle certain figures and images taken from their sacred groves. And what most stimulates their courage is, that their squadrons or battalions, instead of being formed by chance or by a fortuitous gathering, are composed of families and clans. Close by them, too, are those dearest to them, so that they hear the shrieks of women, the cries of infants. They are to every man the most sacred witnesses of his bravery-they are his most generous applauders. The soldier brings his wounds to mother and wife, who shrink not from counting or even demanding them and who administer food and encouragement to the combatants.

“Tradition says that armies already wavering and giving way have been rallied by women who, with earnest entreaties and bosoms laid bare, have vividly represented the horrors of captivity, which the Germans fear with such extreme dread on behalf of their women, that the strongest tie by which a state can be bound is the being required to give, among the number of hostages, maidens of noble birth. They even believe that the sex has a certain sanctity and prescience, and they do not despise their counsels, or make light of their answers. In Vespasian's days we saw Veleda, long regarded by many as a divinity. In former times, too, they venerated Aurinia, and many other women, but not with servile flatteries, or with sham deification.”

Punishments. Administration of Justice: “In their councils an accusation may be preferred or a capital crime prosecuted. Penalties are distinguished according to the offence. Traitors and deserters are hanged on trees; the coward, the unwarlike, the man stained with abominable vices, is plunged into the mire of the morass with a hurdle put over him. This distinction in punishment means that crime, they think, ought, in being punished, to be exposed, while infamy ought to be buried out of sight- Lighter offences, too, have penalties proportioned to them; he who is convicted, is fined in a certain number of horses or of cattle. Half of the fine is paid to the king or to the state, half to the person whose wrongs are avenged and to his relatives.

In these same councils they also elect the chief magistrates, who administer law in the cantons and the towns. Each of these has a hundred associates chosen from the people, who support him with their advice and influence. Marriage Laws. Their marriage code, however, is strict, and indeed no part of their manners is more praiseworthy. Almost alone among barbarians they are content with one wife, except a very few among them, and these not from sensuality, but because their noble birth procures for them many offers of alliance.

Romans murdering Celtic Druids

The wife does not bring a dower to the husband, but the husband to the wife. The parents and relatives are present, and pass judgment on the marriage-gifts, gifts not meant to suit a woman's taste, nor such as a bride would deck herself with, but oxen, a caparisoned steed, a shield, a lance, and a sword. With these presents the wife is espoused, and she herself in her turn brings her husband a gift of arms. This they count their strongest bond of union, these their sacred mysteries, these their gods of marriage. Lest the woman should think herself to stand apart from aspirations after noble deeds and from the perils of war, she is reminded by the ceremony which inaugurates marriage that she is her husband's partner in toil and danger, destined to suffer and to dare with him alike both in war. The yoked oxen, the harnessed steed, the gift of arms proclaim this fact. She must live and die with the feeling that she is receiving what she must hand down to her children neither tarnished nor depreciated, what future daughters-in-law may receive, and maybe so passed on to her grandchildren.

“Thus with their virtue protected they live uncorrupted by the allurements of public shows or the stimulant of feastings. Clandestine correspondence is equally unknown to men and women. Very rare for so numerous a population is adultery, the punishment for which is prompt, and in the husband's power. Having cut off the hair of the adulteress and stripped her naked, he expels her from the house in the presence of her kinsfolk, and then flogs her through the whole village. The loss of chastity meets with no indulgence; neither beauty, youth, nor wealth will procure the culprit a husband. No one in Germany laughs at vice, nor do they call it the fashion to corrupt and to be corrupted. Still better is the condition of those states in which only maidens arc given in marriage, and where the hopes and expectations of a bride are then finally terminated. They receive one husband, as having one body and one life, that they may have no thoughts beyond, no further-reaching desires, that they may love not so much the husband as the married state. To limit the number of children or to destroy any of their subsequent offspring is accounted infamous, and good habits are here more effectual than good laws elsewhere.”

Food: “A liquor for drinking is made of barley or other grain, and fermented into a certain resemblance to wine. The dwellers on the river-bank also buy wine. Their food is of a simple kind, consisting of wild fruit, fresh game, and curdled milk. They satisfy their hunger without elaborate preparation and without delicacies. In quenching their thirst they are equally moderate. If you indulge their love of drinking by supplying them with as much as they desire, they will be overcome by their own vices as easily as by the arms of an enemy.”

Pressures on the Northern Frontiers

Pat Southern wrote for the BBC: “Relations with the northern tribesmen had never been stable, nor were they continually hostile. Rome maintained the upper hand by a combination of diplomacy and warfare, promoting the elite groups among the various tribes and supporting them by means of gifts and subsidies. Sometimes food supplies and even military aid were offered. “Various emperors had settled migrating groups of peoples within the empire and had often recruited tribesmen into the Roman army, where they rendered good service. The very fact of the empire's existence influenced the way in which native society developed on the periphery. When all kinds of dangers threatened the tribes beyond the empire, it probably seemed safer and more lucrative to be on the other side of the Roman frontiers. [Source: Pat Southern, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The ultimate aim of many of the tribes was not necessarily total conquest, but a wish for lands to farm and for protection. This became more necessary to some peoples in the first decades of the third century. Climate changes and a rise in sea levels ruined the agriculture of what is now the Low Countries, forcing tribes to relocate simply to find food. At about the same time, archaeological evidence shows that vigorous, warlike tribesmen moved into the more peaceful lands to the north-west of the empire, precipitating the abandonment of a wide area that was previously settled and agriculturally wealthy. |::|

“The northern world outside the Roman Empire was restless. Raids across the frontiers became more severe, especially in the 230s, when Roman forts and some civilian settlements were partially destroyed. As the power of the tribal federations grew, the Romans began to feel nervous and to think of defensive walls for their unprotected cities. |::|

Germanic Lines

J. A. S. Evans wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: In Germany and Pannonia, the Rhine-Danube line was the frontier, but in the region between the two rivers, where the Neckar valley and the Black Forest offered an invasion route, Domitian had already a chain of small forts and watchtowers. Under the Antonines this system of fortification was completed with walls or palisades linking the forts, towers, and auxiliary bases. [Source: J. A. S. Evans, New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Hallstatt graves

The Germanic Lines, a network of walls and fortifications, extended for 550 kilometers (342 miles) in in Germany. According to UNESCO: “The Upper German-Raetian Limes runs between Rheinbrohl on the Rhine and Eining on the Danube, built in stages during the 2nd century. With its forts, fortlets, physical barriers, linked infrastructure and civilian architecture it exhibits an important interchange of human values through the development of Roman military architecture in previously largely undeveloped areas thereby giving an authentic insight into the world of antiquity of the late 1st to the mid-3rd century AD. It was not solely a military bulwark, but also defined economic and cultural limits. Although cultural influences extended across the frontier, it did represent a cultural divide between the Romanised world and the non-Romanised Germanic peoples. In large parts it was an arbitrary straight line, which did not take account of the topographical circumstances. Therefore, it is an excellent demonstration of the Roman precision in surveying. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage sites website]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: “Nearly 2,000 years ago this was the line that divided the Roman Empire from the rest of the world. Here in Germany the low mound is all that’s left of a wall that once stood some ten feet tall, running hundreds of miles under the wary eyes of Roman soldiers in watchtowers. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, September 2012 ]

“It would have been a shocking sight in the desolate wilderness, 630 miles north of Rome itself. Claus-Michael Hüssen, a researcher with the German Archaeological Institute, told National Geographic, ““The wall here was plastered and painted, “Everything was square and precise. The Romans had a definite idea of how things should be.” Engineering students measuring another stretch of wall found one 31-mile section that curved just 36 inches.

“While Rome looked the other way, barbarian tribes grew bigger and more aggressive and coordinated. When troops were pulled from across the empire to beat back the Persians, weak points in Germany and Romania came under attack almost immediately. Michael Meyer, an archaeologist at Berlin’s Free University.” “The tragic point of their strategy is that the Romans concentrated military force at the frontier. When the Germans attacked the frontier and got in behind the Roman troops, the whole Roman territory was open.” Think of the empire as a cell, and barbarian armies as viruses: Once the empire’s thin outer membrane was breached, invaders had free rein to pillage the interior. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, September 2012]

Battles Between the Romans and Celts

The Celts lost a crucial battle to the Romans at Telamon, Italy in 225 B.C. Even though the Celts captured a Roman consul and waved his head on stake, their courageous but unruly hand-to-hand tactics were no match against the spears and disciplined ranks of the Romans.

To protect his army of 40,000 men from the Gauls in the 1st century B.C., Julius Caesar erected a fortress with a circumference of 20 kilometers. The fort was protected by hidden pits with upward-pointing sticks, logs spiked with iron hooks, walls fashioned from forked timbers and double ditches. The Celts hurled themselves bravely and foolishly at the fortress and were routed after the Roman cavalry charged down from a hill at a strategic time.

The confrontation between Caesar and the Gauls pitted 55,000 Romans against 250,000 Celts. In his eight-year campaign against the Celts in Gaul Caesar wrote he took 800 towns and killed 1,192,00 men, women and children in 30 battles. In one battle alone he reported his army slaughtered over 250,000 Helveteii, a tribe from present-day Switzerland.

In Gaul, Caesar mainly fought Germanic, Celtic tribes. Vercingetorix, the leader of the Celtic forces, surrendered himself at the feet the feet of Caesar who sent him to Rome where the Gaulic leader was imprisoned for six years and ultimately paraded through the streets and strangled in the Forum.

See Separate Articles: GAULS IN PRE-ROMAN AND EARLY REPUBLICAN ITALY europe.factsanddetails.com ; JULIUS CAESAR'S MILITARY CAREER: SKILLS, LEADERSHIP, VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle in the Teutoburg Forest and Defeats in Germany Under Augustus

Nina C. Coppolino wrote: ““In 5 A.D. on the northern frontier Tiberius reached the Elbe, and then tried to subdue the Marcomanni, so that by linking the Elbe with the Danube a new frontier could be established all the way to the Black Sea. His efforts were interrupted and never resumed. In 6 A.D. there was a great and bloody revolt in Pannonia and Dalmatia, which Tiberius finally crushed in 7-8 A.D. in Pannonia, and in 9 A.D. in Dalmatia. Though Tiberius did return to Germany, he and Germanicus were occupied in defending the Rhine after Quinctilius Varus suffered a disastrous defeat there at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, losing three legions and all the territory east of the river. Despite the recovery of the river and forays beyond it, Augustus gave up the thought of a frontier beyond the Rhine. [Source: Nina C. Coppolino, Roman Emperors]

The land of fierce German tribes was held for only about 20 years under the reign of Augustus. German tribes frequently raided towns in Gaul near the border. The land, divided among several German tribes, was lost when three Roman legions were slaughtered at Teutoburg Forest in A.D. 9.

Large Roman Camp in Germany with Huge Bath

According to the Miami Herald: Archaeologists have long known about the Roman military camp of Vetera Castra in Xanten, Germany. Capable of housing up to 10,000 soldiers, the camp was one of the largest in the ancient Roman empire, the LVR Office for Archaeological Preservation in the Rhineland said. To better understand what local life was like, archaeologists took a closer look at the area surrounding the camp, Erich Classen, director of the Office for Archaeological Preservation in the Rhineland, said in an April 20, 2023 Facebook post. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, April 26, 2023]

Magnetic imaging and ground-penetrating radar picked up several structures and walls buried nearby, the release said. Archaeologists excavated the area and unearthed a wealthy ancient Roman suburb. The civilian suburb, also known as a canabae, was much larger and more impressive than experts expected. Excavations uncovered ruins of two large buildings — one wood and one stone — measuring at least 65 feet by 195 feet, the release said.

Archaeologists identified the stone building as a roughly 2,000-year-old public bathhouse. The complex was likely one of the largest such baths in the area during the first century A.D., experts said. Shards of a stained glass window were unearthed. These types of windows were popular in luxurious thermal bath complexes in Rome under Emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 69 A.D., the release said.

The large wooden building was more mysterious. Archaeologists found fragmented roof tiles and burn marks in the ruins, the release said. The rubble indicated the structure was likely destroyed in a fire. Archaeologists believe this suburb matches the layout of a town described by an ancient Roman historian, Tacitus. The first century historian described a town near a legionary camp that was deliberately destroyed by Roman soldiers to prevent the site from being captured during a rebellion, the release said. Xanten is about 390 miles west of Berlin and near the Germany-Netherlands border.

A Roman army under Quictilius Varus was sent in to quell the Germanic tribes but it marched right into a trap. The Battle of Arminius in the Teutoburg Forest brought the Roman expansion into Germany to a halt. Almost every member of a 50,000-member Roman army led by Varus was killed or enslaved. Varus committed suicide. The defeat kept Rome from absorbing German territory. The Germans captured the Roman standards. Augustus was so upset he didn't shave and let hair grow for months. He reportedly also banged his head against a wall, shouting, "Varus! Give me back my legions."

See Separate Article: AUGUSTUS, PAX ROMANA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE europe.factsanddetails.com

German Town Defies the Traditional Roman Narrative

Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: The oft-told tale of the Roman Empire’s expansion is one of violent conquest — its ever-widening borders pushed forward at sword point by Roman legions. Some of the bloodiest military engagements pitted Rome against the inhabitants of Germania, who are described by contemporary sources of the time as a loose confederation of uncivilized, quarrelsome, warlike, ferocious tribes to the north. The conventional wisdom goes that after a decades-long attempt to conquer the region east of the Rhine River finally failed in A.D. 9, Rome gave up on the Germans entirely. But what if there’s more to it than that? [Source:Andrew Curry, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2017]

“In the 1980s, the chance discovery of sherds of Roman-style pottery on a farm in the Lahn Valley near Frankfurt led archaeologists and historians at the German Archaeological Institute’s Romano-Germanic Commission to begin excavations. What they uncovered was a Roman site they call Waldgirmes, after a nearby modern town. When German Archaeological Institute archaeologist Gabriele Rasbach started working at the site in 1993, she and her colleagues assumed they had found a military installation.

“The excavators began to realize that the site might be something else entirely. As they dug over the course of nearly 15 years, they uncovered specialty workshops for ceramics and smithing, and administrative buildings made of local stone and timber from the thick forests nearby. They found evidence of some Roman-style residences with open porticos in front, unlike the longhouse-style buildings preferred by the locals, as well as other hallmarks of a typical Roman town, including a central public space, or forum, and a large administrative building called a basilica. “There’s actually not a single military building inside the walls,” says Rasbach. What they had uncovered was a carefully planned civilian settlement.

Of the hundreds of objects archaeologists have excavated, just five are military in nature, including a few broken spear points and shield nails that could be associated with the army. When taken together, the artifacts and structures persuaded researchers that they were dealing with an entirely novel phenomenon: a new Roman city established from scratch in the middle of a potential province. From the forum to workshops, houses, and water and sewage systems — from which sections of lead pipe have been recovered — to its sturdy outer walls enclosing 20 acres, Waldgirmes had everything a provincial capital needed. “It’s the first time we can see how Rome founded a city,” says von Schnurbein. “You can’t see that anywhere else.”

“Because the site was built predominantly of wood, archaeologists have been able to establish precise dates using dendrochronology, which uses tree rings as a time stamp. They determined that construction at Waldgirmes began around 4 B.C., not long after Roman troops reached the Elbe River, pushing the empire’s range deep into Germany. Waldgirmes’ architecture and the absence of a military presence suggest a relationship between Romans and Germans that runs against both the ancient and modern versions of the accepted story. “The fact that a city was founded in the Lahn Valley without a major military presence means there was a different political situation in the region,” von Schnurbein says — that is, different from what most historians have assumed. He concludes, “The Romans thought the Germans were loyal enough that they could build a civilian settlement here.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The Road Almost Taken” by Andrew Curry in Archaeology magazine archaeology.org

Celts Versus Romans in Britain

Tacitus vividly described a battle in A.D. 61 at Mona, now Anglesey, an island off the coast of northwest Wales, where Celts had gathered in a Druid sanctuary for one last stand against the Romans. Tacitus wrote: "All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers, by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralyzed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds."

The Romans, led by Suetonius Paulinus, arrived on Mona in flat bottom boats and were welcomed by shouting Celtic soldiers and Druid men with long black beards and Druid women in black cloaks, who waved flaming torches and caste out curses. The Roman soldiers hesitated at first, never having been greeted by such as bizarre spectacle before, but were urged on by Paulinus. The Romans ended up slaughtering every Celt they could lay their hands on and chopped sacred trees in the Druid sanctuary.

Tacitus wrote in “The Annals” Book XIV (A.D. 110-120): “During the consulship of Lucius Caesennius Paetus and Publius Petronius Turpilianus [AD 60-61], a dreadful calamity befell the army in Britain. Aulus Didius, as has been mentioned, aimed at no extension of territory, content with maintaining the conquests already made. Veranius, who succeeded him, did little more: he made a few incursions into the country of the Silures, and was hindered by death from prosecuting the war with vigour. He had been respected, during his life, for the severity of his manners; in his end, the mark fell off, and his last will discovered the low ambition of a servile flatterer, who, in those moments, could offer incense to Nero, and add, with vain ostentation, that if he lived two years, it was his design to make the whole island obedient to the authority of the prince. [Source: Chapter 29: Military campaign in Wales, Tacitus: (A.D. 56–120): Boudicca, “The Annals 14: 29-37, translation from Latin is adapted from Arthur Murphy (“Works of Tacitus”, 1794)]

“Paulinus Suetonius succeeded to the command; an officer of distinguished merit. To be compared with Corbulo was his ambition. His military talents gave him pretensions, and the voice of the people, who never leave exalted merit without a rival, raised him to the highest eminence. By subduing the mutinous spirit of the Britons he hoped to equal the brilliant success of Corbulo in Armenia. With this view, he resolved to subdue the isle of Mona; a place in habited by a warlike people, and a common refuge for all the discontented Britons. In order to facilitate his approach to a difficult and deceitful shore, he ordered a number of flat-bottomed boats to be constructed. In these he wafted over the infantry, while the cavalry, partly by fording over the shallows, and partly by swimming their horses, advanced to gain a footing on the island.

“On the opposite shore stood the Britons, close embodied, and prepared for action. Women were seen running through the ranks in wild disorder; their apparel funeral; their hair loose to the wind, in their hands flaming torches, and their whole appearance resembling the frantic rage of the Furies. The Druids were ranged in order, with hands uplifted, invoking the gods, and pouring forth horrible imprecations. The novelty of the fight struck the Romans with awe and terror. They stood in stupid amazement, as if their limbs were benumbed, riveted to one spot, a mark for the enemy. The exhortations of the general diffused new vigour through the ranks, and the men, by mutual reproaches, inflamed each other to deeds of valour. They felt the disgrace of yielding to a troop of women, and a band of fanatic priests; they advanced their standards, and rushed on to the attack with impetuous fury. [Source: Chapter 30: The Druids at Mona Island, Tacitus (A.D. 56–120): Boudicca, “The Annals 14: 29-37, translation from Latin is adapted from Arthur Murphy (“Works of Tacitus”, 1794)]

“The Britons perished in the flames, which they themselves had kindled. The island fell, and a garrison was established to retain it in subjection. The religious groves, dedicated to superstition and barbarous rites, were levelled to the ground. In those recesses, the natives [stained] their altars with the blood of their prisoners, and in the entrails of men explored the will of the gods. While Suetonius was employed in making his arrangements to secure the island, he received intelligence that Britain had revolted, and that the whole province was up in arms.”

Romans in the Netherlands and Belgium

According to Archaeology Magazine: A Roman sanctuary unearthed at a clay extraction site in the Netherlands is giving researchers insights into life on the empire’s northern boundary. Discovered in the town of Herwen-Hemeling, the sanctuary was used between the first and fourth centuries A.D. by soldiers along the Roman Limes, the outermost edges of the empire. Archaeologists found remnants of two temples, sculptures and reliefs, evidence of animal sacrifices, various artifacts, and an area with dozens of votive stones — inscribed altars dedicated by Roman generals to gods such as Hercules Magusanus, Mercury, and Jupiter Serapis. [Source: Elizabeth Hewitt, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Project leader Eric Norde of RAAP Archaeological Consultancy says that, based on pottery sherds that match the wheel-thrown variety used by Romans, not the handmade pottery of local Batavians, it seems that the sanctuary was primarily used by Roman soldiers. Some of them had connections to distant corners of the empire. For example, Norde has identified inscriptions mentioning a high-ranking officer from Africa and the unit Cohors II Asturum, which was based in northern Spain. “In Roman times, the Netherlands were just the bloody middle of nowhere, and here we find traces of Roman soldiers coming out of Africa, out of Spain,” Norde says. “It’s just amazing.”

In reference to another discovery: Most ancient Romans probably couldn’t swim, so they put their lives at risk whenever they needed to cross a river. Sometimes, they would entreat protective gods to provide them safe passage. A collection of more than 100 coins dating from the 1st century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. found near the town of Berlicum likely marks the spot where Roman travelers once forded the River Aa and tossed coins into the water as offerings, hoping to reach the opposite shore unharmed. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September 2021]

In Elewijt Belgium, burnt graves full of ancient Roman artifacts were uncovered during construction. Moira Ritter wrote in the Miami Herald: In total, there were 30 burnt graves buried at the site, complete with a collection of burial artifacts. Among the graves, archaeologists discovered several earthenware jars, burnt glass and fragments of glass paste from a decorated pin dating to sometime between the second and third century. There were also at least nine circular ditches found — some of which dated to the Iron Age and others that dated to the Roman empire. Most surprising, experts discovered an open air shrine dating to the early Roman period, they said. [Source Moira Ritter, Miami Herald, April 27, 2023]

Roman Coins and Bronze Owl Discovered in Scandinavia

In April 2023, archaeologists said they were surprised by the discovery of two silver coins from the Roman Empire on a remote island in the Baltic Sea, halfway between Sweden and Estonia. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: No clues reveal how the coins got there, but they may have been left by Norse traders, lost in a shipwreck or brought there on a Roman ship that voyaged to the far north. Johan Rönnby, an archaeologist at Södertörn University in Stockholm, was part of the team that found the coins with metal detectors at a beach site marked by old fireplaces on the island of Gotska Sandön. "We were so happy," he told Live Science. "We have this site, but we don't know what it is. But now that we have the coins there, it makes it even more interesting to continue to excavate it." [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, April 14, 2023]

The two silver coins found on the island are both Roman "denarii" — one from the reign of the emperor Trajan, between A.D. 98 and 117, and the other from the reign of the emperor Antoninus Pius, between A.D. 138 and 161. They each weigh less than an eighth of an ounce (4 grams) and would have represented about a day's pay for a laborer when they were minted. Roman coins have also been found on the larger island of Gotland about 25 miles (40 kilometers) to the south, but that was perhaps to be expected because it was the location of several towns. Gotska Sandön, however, has no towns or villages.

Rönnby said coins from the Roman Empire could have stayed in circulation for a long time, because the silver they contained always remained valuable; and they might have been brought to Gotska Sandön by Norse traders who had taken shelter there from storms at sea. But it's also possible they were carried there by survivors from a shipwreck: The waters around the island are notoriously dangerous, and the area is littered with wrecks, he said. Another possibility is that the coins were taken to Gotska Sandön by Romans on a Roman ship, though no records of such a voyage into the Baltic exist. "It's not likely to be a Roman ship," Rönnby said. "But you have to consider also that the Romans were sailing up to Scotland and so on, and that there were Roman authors at that time writing about the Baltic area."

In 2015, Archaeology magazine reported: Danish archaeologists investigating the settlement of Lavegaard on the island of Bornholm have uncovered an unusual and exquisite owl-shaped fibula. The 1.5-by-1.5-inch Roman brooch, which dates to the first through third centuries A.D., was discovered by metal detectorists working with the Bornholm Museum. The bronze owl is inlaid with enamel disks and colored glass, which were used to create the enormous orange-and-black eyes. Decorative enameled fibulas are rare in such remote areas of northern Europe, with most concentrated in Roman frontier forts along the Danube or Rhine. This valuable personal item was likely brought back to Bornholm by a local mercenary who had served along the frontier, or was perhaps a gift from a wealthy Roman visiting the island. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024