Home | Category: Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

EARLY ROME — THE KINGDOM

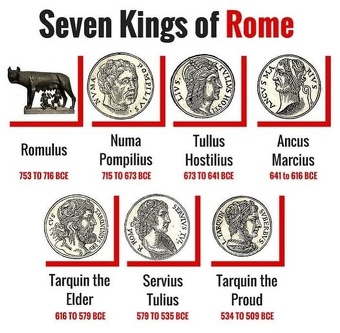

Javier Negrete wrote in National Geographic History: Before it was an empire, before it was a republic — Rome was a kingdom. Its legendary founder Romulus, was the first rex, or king. According to tradition, his reign began in 753 B.C. Rome is believed to have had seven kings in all, and the monarchy lasted for more than 240 years. Unlike the other rexes, the last three kings — Tarquin the Elder, Servius Tullius, and Tarquin the Proud — all shared Etruscan ancestry, tracing it back to a civilization that flourished in central Italy between the eighth and third centuries B.C. Of all Rome’s royalty, they perhaps made the biggest impact on the Eternal City. [Source: Javier Negrete, National Geographic History, July 13, 2023]

Accurate records of these times, however, are scant. Some sources are conflicting, and many of the most popular ones, such as the first-century B.C. historian Titus Livius (Livy), were compiled centuries after the events they describe, making it difficult to take their accounts at face value. Many of these accounts also blend the fantastic with the everyday.

According to National Geographic History: While modern scholars discount some of the accounts of ancient Roman historians, they agree that during the first phase of its history—from approximately 753 to 509 B.C.—Rome was ruled by kings. According to these writers, Romulus was the first, succeeded by Numa Pompilius, a Sabine, and in 616 B.C. by an Etruscan named L. Tarquinius Priscus. [Source: Jane von Mehren, National Geographic History, January 11, 2023]

Gaius Mucius Scaevola was a legendary Roman hero, who attempted to assassinate the enemy Etruscan king Lars Porsena in the sixth-century B.C. When Scaevola failed to kill the king, he was captured and brought before Lars. But instead of pleading for clemency, Scaevola declared boldly: Romanus sum—I am a Roman, before delivering a stirring speech on the bravery of his people. The king was so impressed that, the story goes, he let Scaevola go.[Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FOUNDING OF ROME: DIFFERENT STORIES, MYTHS AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMULUS AND REMUS: STORIES, LEGENDS, ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY ROMANS AND THE SABINES: RAPE, BATTLES AND UNIFICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMANS AND ETRUSCANS: INFLUENCES, BATTLES AND LEGENDARY KINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LAST THREE KINGS OF EARLY ROME: LEGENDS, ETRUSCAN ORIGINS, VIOLENCE, UPHEAVAL europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Early Rome to 290 BC: The Beginnings of the City and the Rise of the Republic” by Guy Bradley (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Rome: From the Iron Age to the Punic Wars” by Kathryn Lomas (2018) Amazon.com;

“A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War”

by Gary Forsythe (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire” by Anthony Everitt (2013) Amazon.com;

“Livy: The Early History of Rome, Books I-V” (Penguin Classics)

by Titus Livy , Aubrey de Sélincourt , et al. (2002) Amazon.com

“Romulus: The Legend of Rome's Founding Father” by Marc Hyden (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium” by Ross R. Holloway (2014) Amazon.com;

“Latium: Prelude to the Roman Kingdom” by Peter Tattersall (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium” by Ross R. Holloway (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Urbanisation of Rome and Latium Vetus: From the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era”

by Francesca Fulminante (2014), ebook Amazon.com;

"Italy Before Rome: A Sourcebook" (Routledge) by Katherine McDonald (2021) Amazon.com

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Italy Before the Romans: The Iron Age” by David Ridgway Amazon.com

“Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies” by Larissa Bonfante, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (1986) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans” by Graeme Barker, Tom Rasmussen (1998) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History” by Sybille Haynes (2005) Amazon.com;

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Conquest of Italy” by Jean-Michel David and Antonia Nevill (1996)

Amazon.com

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Pre-Roman Italy (1000–49 BCE) by Jane Botsford Johnson and Marco Maiuro (2024) Amazon.com;

“Production, Trade, and Connectivity in Pre-Roman Italy (Routledge) by Jeremy Armstrong and Sheira Cohen (2022) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

Seven Kings and Expanding Walls of Rome

As there are seven hills of Rome (Quirinal, Viminal, Capitoline, Esquiline, Palatine, Caelian and Aventine), there are seven kings of Rome — Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. [Source:Hanna Seariac, Deseret News, April 22, 2023]

Hanna Seariac wrote in the Deseret News: Each of these kings contributed to the development of Rome. Numa Pompilius was known for religious reforms and establishing religious groups (commonly referred to as cults in historical research — different meaning and connotation than the common use of the word). He also extended the calendar to 12 months from 10. Other kings like Tullus Hostilius built the curia (senate house) or as Ancus Marcius did, establish a bridge over the Tiber.

The Servian wall was built around Rome by Servius Tullius and Rome became an established monarchy. Then, Tarquinius Superbus became king. He built a giant sewer known as Cloaca Maxima and he commissioned the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, which was a primary space of worship for the ancient Romans. Notably, from the Cumaean Sibyl (an oracular priestess), he purchased the Sibylline Books, which were believed to contain important prophecies about the future of Rome. They also contain specific worship instructions. Then, as Livy recounted it, Sextus Tarquinius, son of Tarquinius Superbus, raped Lucretia, who died by suicide. Then, her father and her husband staged a rebellion which led to the end of the Roman monarchy.

Pre-Republic development of Rome was divided into four regions: Palatina, Esquilina, Suburana, and Collina, the last comprising the Quirinal and the Viminal. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Surrounding walls were constructed. Tradition attributes these initiatives to the next-to-last king, Servius Tullius. Recent archaeological discoveries have verified a notable territorial extension of the city during the sixth century B.C. As for the ramparts, if the date of the wall made by Servius in opus quadratum should be advanced to the fourth century B.C., after the burning of Rome by the Gauls, the existence of walls in the sixth century is nonetheless established by the vestiges of an agger found on the Quirinal. The discovery at Lavinium of a rampart in opus quadratum dating from the sixth century B.C. leads, analogously to the Roman situation, to the same conclusion. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

Numa, the Second Roman King and Founder of Roman Religion

Numa

A Sabine named Numa Pompilius was elected as the second king of Rome. He is said to have been a very wise and pious man, and to have taught the Romans the arts of peace and the worship of the gods. Numa is represented in the legends as the founder of the Roman religion. He appointed priests and other ministers of religion. He divided the lands among the people, placing boundaries under the charge of the god Terminus. He is also said to have divided the year into twelve months, and thus to have founded the Roman calendar. After a peaceful reign of forty-two years, he was buried under the hill Janiculum, across the Tiber. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Roman tradition ascribed to Numa, second of the seven kings, the organization of the worship and the assignment to the calendar of the proper festivals in due order. Whether or not we choose to believe that a great priest-king left his personal impress on ritual and calendar, “the religion of Numa” is a convenient phrase by which to designate the religion of the early State. Numa was supposed to have organized the first priestly colleges and to have appointed the first flamines, or priests of special gods. The most important of these were the Flamen Dialis, or priest of Jupiter, and the flamines of Mars and Quirinus. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“When the kingship was abolished, the office of rex sacrorum was instituted to carry on the rites once in the charge of the king. He, the three flamines mentioned above, and the college of the pontifices, with the Pontifex Maximus at its head, constituted the body controlling and guiding the state religion. Under the Empire the emperor was regularly Pontifex Maximus. |+|

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Plutarch's life reveals, by its markedly polemical tone, the extent to which the facts about the regal period were being debated by antiquarians in the late Republic. Known as the establisher of the Roman state religion, Numa was credited with the establishment or regularization of the main religious figures and officials in Rome, including the pontifices, vestals, and flamines. He is supposed as well to have been responsible for the formation of the calendar; it is fairly certain that the Roman calendar actually came into use some one hundred years later. The calendar is interesting as an index of the way religion might have functioned as a means of social control, how closely intertwined were the exercises of sacred and secular power. The Roman senate, after all, met in a temple. One of the many inheritances the Romans had from the Etruscans was the art of divination, of looking into the future by means of observing the flights of birds or the entrails of sacrificial victims. For any major public undertaking it was necessary to determine whether the gods would be favorable to it at any one time; moreover, certain days were automatically favorable days for the conduct of public business, while other days were certainly not (dies fasti and dies nefasti). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Only the holder of one of the highest of the traditional magistracies, the curule officials, had the right to take the auspices; the curule magistracies were originally just the two consuls. (Compare the Etruscan plaque from Caere, showing the king seated on the curule throne; = Scullard, Etruscan Cities pl. 100). In their absence the curule magistrates were the dictator and his master of horse (magister equitum); later other curule magistracies were added (the praetor, censor, and curule aedile). The extent to which the patres monopolized the right to take the auspices and presence in the priestly colleges is disputed, but it is clear that from an early stage declaring a day nefas could bring any planned public proceedings to a halt. It is significant that the Roman calendar was not published until 304 B.C., and that the opening of all of the priesthoods to the plebeians was supposed to have been one of the last concessions won in the struggle of the orders (by the lex Ogulnia). ^*^

Did Numa Really Exist?

Numa and the nymph Egeria

The historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “To Numa, the traditional second king of Rome (assumed dates 715 to 673 B.C.) later ages attributed many of the religious usages of the city. We may dismiss Numa as legendary; but the institutions and customs ascribed to him were not legendary, and survived nearly intact down to the triumph of Christianity, thus illustrating the essentially conservative character of the Roman genius. Note that the old Roman religion was almost formalism incarnate. The relations of god and worshiper are those of creditor and debtor; the latter must discharge his duty literally, and in exchange require a due amount of favor. Almost no religion was so deficient in spirituality as that of Rome. It did, however, put a premium on the scrupulous performance of duty. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 9-15.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: ““There may be a way to finding a historical kernel to the annalistic tradition through Numa. His name ought to be Etruscan, although Plutarch identifies him as Sabine and Pompilius could be either Sabine or Etruscan. Plutarch has Numa living in the Regia, and this building's remains in the Forum Romanum may hold a clue. The earliest object to emerge from the excavation of it is a Bucchero cup, dating to around 625 B.C. and having the word REX painted on it; this, at least, seems to confirm that there were kings at Rome. Excavation has also revealed that there were a number of phases of construction on the Regia, with the earliest of them going back into the seventh century. The first phase shows a courtyard, with a portico at one end and two chambers with a space between them. In the second phase, the courtyard is extended to enclose the two chambers. In the third phase, dated to around 550 B.C., a door was added in the north wall and one of the chambers was eliminated; to this phase belong a series of architectural terracottas. After a destruction by fire around 530 B.C., the Regia was rebuilt with a ground plan similar to that of the original, but with a new orientation. It was redesigned one final time at the end of the sixth century (phase 5) and that plan was retained in all subsequent renovations. Through all of the stages the Regia has more in common with domestic than with sacred architecture. In other words, for what it is worth, the ground plan of the building suggests that the early Roman king was a priest but not a god, and that tallies with the account of the annalistic tradition. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Finally, there is the lapis niger, discovered in 1899 by the northern corner of the Forum Romanum at the foot of the Capitoline. Roman authors believed that the lapis niger marked a tomb, which they identify variously as that of Faustulus (the shepherd who rescued Romulus and Remus), or Hostilius (grandfather of the king Tullus Hostilius; DH 3.1.2), or Romulus himself. Actually, as it turned out, no one was buried there. The stone was not a grave marker but rather a king of boundary stone marking off a sacred precinct. It is dated on the basis of the letter forms to the second quarter of the sixth century B.C. The tufa rock is of the same type as that used in the Servian Wall (Grotto Oscura), but the date finds confirmation from the pottery in the fill in a pool next to the monument. The text is a sacred law, probably establishing the spot as inviolable. It mentions the king twice in the dative case; other secure words include: sakros 'cursed' iouxmenta 'oath' iouested 'just'. In sum, the lapis niger confirms the presence of kings at Rome, at least towards the end of what the annalist thought of as the regal period, and confirms too that they had some religious role. It does not, however, get us any closer to someone named Numa Pompilius. Neither can we find archaeological confirmation for any building supposed to have been raised by Numa's successor, Tullus Hostilius. The building of the first Curia is attributed to him (Varro Ling. 5.155); the Curia Hostilia is the meeting place of the senate of Rome. But there are no archaeological traces, because it was completely rebuilt as the Curia Julia by Augustus in 29 B.C. However, Tullus Hostilius (who was primarily remembered as a warrior king) is supposed to have captured Alba Longa, and as we have seen the evidence from the early graves does show a close affinity between the people of the Alban Hills and those on the site of Rome.”

Ancus Marcius and Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Ancus Marcius

The third king, Tullus Hostilius, was chosen from the Romans. His reign was noted for the conquest of Alba Longa. In accounts of this war with Alba Longa, the famous story is told of the Horatii and the Curiatii, three brothers in each army, who were selected to decide the contest by a combat, which resulted in favor of the Horatii, the Roman champions. Alba Longa thus became subject to Rome. Afterward, Alba Longa was razed to the ground, and all its people were transferred to Rome. Tullus, it is said, neglected the worship of the gods, and was at last, with his whole house, destroyed by the lightnings of Jove. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

After the reign of Tullus the people elected Ancus Marcius, a Sabine and a grandson of Numa Pompilius. He is said to have published the sacred laws of his grandfather, and to have tried to restore the arts of peace. But, threatened by the Latins, he conquered many of their cities, brought their inhabitants to Rome, and settled them upon the Aventine hill. He fortified the hill Janiculum, on the other side of the Tiber, to protect Rome from the Etruscans, and built across the river a wooden bridge (the Pons Sublicius). He also conquered the lands between Rome and the sea and built the port of Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber. \~\

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Ancus Marcius is, as Momigliano called him, “an inconsistent figure.” The tradition describes him as a peaceful man, but goes on to tot up his conquests, at Politorium (possibly = Castel di Decima), Tellecenae, Ficana. He is also credited with the foundation of the colony at Ostia, the port of Rome; this looks to be wildly false, as archaeology reveals no trace of permanent settlement at Ostia prior to the fourth century B.C. But Scullard sees a kernel of truth, supposing that the story could reflect the acquisition of control by the Romans over the salt flats on the south bank of the Tiber at Ostia. Scullard also accepts the idea that Ancus built the first bridge over the Tiber (the Pons Sublicius); this can not be proved, but if correct it is suggestive, because of the etymological connection between bridge-building and the priesthood (pontifex; rejected, probably wrongly, by Plutarch). Ancus Marcius is also assigned the institution of the declaration of war by the fetiales (Livy 1. 32, cf. 1. 24). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Tarquin and the Eagle

“With Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, we begin to move into the period where less reaching is involved in making connections between the archaeological record and the annalistic tradition. We read in Livy the story of how the Corinthian exile, Demaratus, came to settle in Etruria, and how his son Lucumo became the king of Rome. Etruscan inscriptions, at least, show that there were persons of mixed Greek and Etruscan descent, such as Rutile Hipukrates (Rutulus Hippokrates). Also, Tarquin is obviously an Etruscan name (a major Etruscan city was called Tarquinii).

“The elder Tarquin was also supposed to have vowed the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (together with Minerva and Juno) on the Capitoline; both Livy (1. 56) and Dionysius (4. 59-61) record that the temple was dedicated by Priscus and completed by Superbus, then finally consecrated in the first year of the Republic, 509 B.C. Support for this is supposed to come from the Pontifical fasti (seen at Livy 2.8 and Polybius 3. 22, giving the name of Marcus Horatius). The custom was to put a nail in the wall of Jupiter's temple to mark each new year, and according to Pliny when the nails were counted in the year 304 there were 204 of them (NH 31. 19). This seems fairly strong. But the skeptics point out that there was a consular tribune of the same name as the consul of the first year of the Republic in 378 B.C. Moreover, looking at the preserved foundations of the temple, which was rebuilt in 83 B.C. on the original foundations, a change of around ten centimeters in the height of the building blocks can be observed from the twelfth course upwards. This suggests that work on the temple was suspended for some lengthy period of time and then resumed. Thus, while a delay in the building process is also built in to the traditional account, it is possible that the temple in its completed form is a work of the 4th century B.C. Its monumental size certainly fits that period better from a historical point of view. Although the annalists attempt to suggest that early Rome was already quite powerful, extending its dominion over its neighbors in Latium from the start of the Republican period, there is more than one reason to believe that this is mere boosterism on the part of the annalistic tradition.

Hills of Rome and Their Perspective on Rome’s Early History

“To obtain a more definite knowledge of the birth of Rome than we can get from the traditional stories, we must study that famous group of hills which may be called the “cradle of the Roman people.” By looking at these hills, we can see quite clearly how Rome must have come into being, and how it became a powerful city. The location of these hills was favorable for defense, and for the beginning of a strong settlement. Situated about eighteen miles from the mouth of the Tiber, they were far enough removed from the sea to be secure from the attacks of the pirates that infested these waters; while the river afforded an easy highway for commerce. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

To understand the relation of these hills to one another, we may consider them as forming two groups, the northern and the southern. The southern group comprised three hills—the Palatine, the Caelian, and the Aventine—arranged in the form of a triangle, with the Palatine projecting to the north. The northern group comprised four hills, arranged in the form of a crescent or semicircle, in the following order, beginning from the east: the Esquiline, the Viminal, the Quirinal, and the Capitoline—the last being a sort of spur of the Quirinal. These two groups of hills became, as we shall see, the seats of two different settlements. Of all the hills on the Tiber, the Palatine occupied the most central and commanding position. It was, therefore, the people of the Palatine settlement who would naturally become the controlling people of the seven-hilled city.

By looking at the neighboring lands about the Tiber we see that Rome was located at the point of contact between three important countries. On the south and east was Latium, the country of the Latins, already dotted with a number of cities, the most important of which was Alba Longa. On the north was the country of the Sabines, a branch of the Sabellian stock. On the northwest was Etruria, with a large number of cities organized in confederacies and inhabited by the most civilized and enterprising people of central Italy. The peoples of these three different countries were pushing their outposts in the direction of the seven hills. It is not difficult for us to see that the time must come when there would be a struggle for the possession of this important locality. \~\

What Early Rome Was Like

Seven Hills of Rome

As far as we know, the first people to get a foothold upon the site of Rome were the Latins, who formed a settlement about the Palatine hill. This Latin settlement was at first a small village. It consisted of a few farmers and shepherds who were sent out from Latium (perhaps from Alba Longa) as a sort of outpost, both to protect the Latin frontier and to trade with the neighboring tribes. The people who formed this settlement were called Ramnes. They dwelt in their rude straw huts on the slopes of the Palatine, and on the lower lands in the direction of the Aventine and the Caelian. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The outlying lands furnished the fields which they tilled and used for pasturage. In order to protect them from attacks, the sides of the Palatine hill were strengthened by a wall built of rude but solid masonry. This fortified place was called Roma Quadrata,1 or “Square Rome.” It formed the citadel of the colony, into which the settlers could drive their cattle and conduct their families when attacked by hostile neighbors. What some persons suppose to be the primitive wall of the Palatine city, known as the Wall of Romulus, has in recent years been uncovered, showing the general character of this first fortification of Rome. \~\

Early Roman Society

Scholars are fairly well agreed that the city of Rome grew out of a settlement of Latin shepherds and farmers on the Palatine hill; and that this first settlement slowly expanded by taking in and uniting with itself the settlements established on the other hills. But to understand more fully the beginnings of this little city-state, we must look at the way in which the people were organized; how they were ruled; and how their society and government were held together and made strong by a common religion. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Classes were divided into centuries of equal wealth. Though the richer classes had fewer individuals in their centuries, each individual had more power, since each century voted as a bloc. In later eras, the census was used to levy taxes.

Roman Gens: A number of families which were supposed to be descended from a common ancestor formed a clan, or gens. Like the family, the gens was bound together by common religious rites. It was also governed by a common chief or ruler (decurio), who performed the religious rites, and led the people in war. \~\

Roman Curia: A number of gentes formed a still larger group, called a curia. In ancient times, when different people wished to unite, it was customary for them to make the union sacred by worshiping some common god. So the curia was bound together by the worship of a common deity. To preside over the common worship, a chief (curio) was selected, who was also the military commander in time of war, and chief magistrate in time of peace. The chief was assisted by a council of elders; and upon the most important questions he consulted the members of the curia in a common place of meeting (comitium). So that the curia was a small confederation of gentes, and made what we might call a little state. \~\

Roman Tribes: There was in the early Roman society a still larger group than the curia; it was what was called the tribe. It was a collection of curiae which had united for purposes of common defense and had come to form quite a distinct and well-organized community, like that which had settled upon the Palatine hill, and also like the Sabine community which had settled upon the Quirinal. Each of these settlements was therefore a tribe. Each had its chief, or king (rex), who was priest of the common religion, military commander in time of war, and civil magistrate to settle all disputes. Like the curia, it had also a council of elders and a general assembly of all people capable of bearing arms. Three of such tribes formed the whole Roman people. \~\

Monarchal Rule in Pre-Republican Rome

Jane von Mehren wrote in National Geographic History: Kings had almost absolute power, serving as administrative, judicial, military, and religious leaders. A senate acted as an advisory council. The king chose its members, who became known as patricians, from the city’s leading families. [Source: Jane von Mehren, National Geographic History, January 11, 2023]

Unlike later monarchs, Roman kingship was not inherited. After a king died, there was a period known as an interregnum, when the Senate chose a new ruler, who was then elected by the people of Rome. The king-elect needed to obtain approval of the gods and the imperium, the power to command, before assuming his throne.

Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome, is said to have organized the first census. He placed people into three tribes consisting of ten wards, or curiae, from which the king chose 300 patricians to sit in the Senate. His successor, Servius Tullius, reorganized citizens into five wealth-based classes.

Early Roman Government

In the early days or Rome, each of the tribes had its own chief, council of elders, and general assembly. When the tribes on the Palatine and Quirinal hills united and became one people, their governments were also united and became one government. For example, their two chiefs were replaced by one king chosen alternately from each tribe. Their two councils of one hundred members each were united in a single council of two hundred members. Their two assemblies, each one of which was made up of ten curiae, were combined into a single assembly of twenty curiae. And when the third tribe is added, we have a single king, a council of elders made up of three hundred members, and an assembly of the people composed of thirty curiae. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

The Roman king was the chief of the whole people. He was elected by all the people in their common assembly and inaugurated under the approval of the gods. He was in a sense the father of the whole nation. He was the chief priest of the national religion. He was the military commander of the people, whom he called to arms in time of war. He administered law and justice, and like the father of the household had the power of life and death over all his subjects. \~\

The Roman Senate: The council of elders for the united city was called the senate (from senex, an old man). It was composed of the chief men of the gentes, chosen by the king to assist him with their advice. It comprised at first one hundred members, then two hundred, and finally three hundred—the original number having been doubled and tripled, with the addition of the second and third tribes. The senate at first had no power to make laws, only the power to give advice, which the king might accept or not, as he pleased. \~\

The Comitia Curiata: All the people of the thirty curiae, capable of bearing arms, formed a general assembly of the united city, called the comitia curiata. In this assembly each curia had a single vote, and the will of the assembly was determined by a majority of such votes. In a certain sense the comitia curiata was the ultimate authority in the state. It elected the king and passed a law conferring upon him his power. It ratified or rejected the most important proposals of the king regarding peace and war. The early city-state of Rome may then be described as a democratic monarchy, in which the power of the king was based upon the will of the people. \~\

The oldest Roman government was based upon the patrician class. Over time the separation between the patricians and the plebeians was gradually broken down, with old patrician aristocracy passing away, and Rome becoming in theory, a democratic republic. Everyone who was enrolled in the thirty-five tribes was a full Roman citizen, and had a share in the government. But we must remember that not all the persons who were under the Roman authority were full Roman citizens. The inhabitants of the Latin colonies were not full Roman citizens. They could not hold office, and only under certain conditions could they vote. The Italian allies were not citizens at all, and could neither vote nor hold office. And now the conquests had added millions of people to those who were not citizens. The Roman world was, in fact, governed by the comparatively few people who lived in and about the city of Rome. But even within this class of citizens at Rome, there had gradually grown up a smaller body of persons, who became the real holders of political power. Later, this small body formed a new nobility—the optimates. All who had held the office of consul, praetor, or curule aedile—that is, a “curule office”—were regarded as nobles (nobiles), and their families were distinguished by the right of setting up the ancestral images in their homes (ius imaginis). Any citizen might, it is true, be elected to the curule offices; but the noble families were able, by their wealth, to influence the elections, so as practically to retain these offices in their own hands. \~\

Palatime Hill huts

Roman Way of Declaring War in 650 B.C.

On the following document, the American historian William Stearns Davis wrote: “Among the very old formulas and usages that survived at Rome down to relatively late times, this method of declaring war holds a notable place. It was highly needful to observe all the necessary formalities in beginning hostilities, otherwise the angry gods would turn their favor to the enemy. Ancus Marcius, the fourth king of Rome, was at once a man of peace and an efficient soldier; and on the outbreak of a war with the Latins he is said to have instituted the customs which later ages of Romans observed in war.”

On the Roman Way of Declaring War around 650 B.C., the Roman historian Livy (59 B.C.- A.D. 17 ) Wrote in “History of Rome” I. 32: “Inasmuch as Numa had instituted the religious rites for days of peace, Ancus Marcius desired that the ceremonies relating to war might be transmitted by himself to future ages. Accordingly he borrowed from an ancient folk, the Aequicolae, the form which the [Roman] heralds still observe, when they make public demand for restitution. The [Roman] envoy when he comes to the frontier of the offending nation, covers his head with a woolen fillet, and says: Hear, O Jupiter, and hear ye lands _____ [i.e., of such and such a nation], let Justice hear! I am a public messenger of the Roman people. Justly and religiously I come, and let my words bear credit! Then he makes his demands, and follows with a solemn appeal to Jupiter. If I demand unjustly and impiously that these men and goods [in question] be given to me, the herald of the Roman people, then suffer me never to enjoy again my native country! [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 7-9.

“These words he repeats when he crosses the frontiers; he says them also to the first man he meets [on the way]; again when he passes the gate; again on entering the [foreigners'] market-place, some few words in the formula being changed. If the persons he demands are not surrendered after thirty days, he declares war, thus: Hear, O Jupiter and you too, Juno---Romulus also, and all the celestial, terrestrial, and infernal gods! Give us ear! I call you to witness that this nation _____ is unjust, and has acted contrary to right. And as for us, we will consult thereon with our elders in our homeland, as to how we may obtain our rights.

“After that the envoy returns to Rome to report, and the king was wont at once to consult with the Senators in some such words as these, Concerning such quarrels as to which the pater patratus [i.e., the head of the Roman heralds] of the Roman people has conferred with the pater patratus of the ____ people, and with that people themselves, touching what they ought to have surrendered or done and which things they have not surrendered nor done [as they ought]; speak forth, he said to the senator first questioned, what think you? Then the other said, I think that [our rights] should be demanded by a just and properly declared war, and for that I give my consent and vote. Next the others were asked in order, and when the majority of those present had reached an agreement, the war was resolved upon.

“It was customary for the fetialis to carry in his hand a javelin pointed with steel, or burnt at the end and dipped in blood. This he took to the confines of the enemy's country, and in the presence of at least three persons of adult years, he spoke thus: Forasmuch as the state of the __ has offended against the Roman People, the Quirites; and forasmuch as the Roman People the Quirites have ordered that there should be war with and the Senate of the Roman People has duly voted that war should be made upon the enemy ___ : I, acting for the Roman People, declare and make actual war upon the enemy!

“So saying he flung the spear within the hostile confines. After this manner restitution was at that time demanded from the Latins [by Ancus Marcius] and war proclaimed; and the usage then established was adopted by posterity.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024