Home | Category: Etruscans, Pre-Romans and Pre-Republican Rome

FOUNDING OF ROME

Romulus and Remus Rome was founded, according to myth, on April 21, 753 B.C. Roman authors often dated important events using this as a starting date with the acronym A.U.C. — ab urbe condita or “from the founding of the city.” The legendary founding of the city is described by Livy, Virgil and other Roman writers. [Source: Hanna Seariac, Deseret News, April 22, 2023]

According to legend, even as told by reputable historians such as Fabius, Livy, and Plutarch, Rome was founded by the wolf-suckled twins Romulus and Remus. The name Rome is said to have come from a combination of the names Romulus and Remus but scholars believe it comes from a Greek or Etruscan word, perhaps “ rhome” , a Greek word meaning "strong." Romulus and the Sabine leader Titus Tatius are said to have met to end a war that triggered the infamous rape of the Sabine women by the followers of Romulus.

According to legend Palatine Hill is where Romulus and Remus were suckled by their she wolf mother and where Rome was founded in the 8th century B.C., when Romulus killed Remus there. The most interesting piece in the Capitoline Museum in Rome is a famous Etruscan bronze of a crazy-eyed she-wolf being. Renaissance depictions of Romulus and Remus were added to the statue in the 15th century.

While mythical Romulus and Remus get the credit for the founding of Rome, archaeological evidences tells a different story. It says the first Romans were Latin farmers and shepherds living in small village huts on the Esquiline and Palatine hills. The Sabines, a tribe living to the north, divided soon after the city’s founding, and some of them came south and united with Rome’s people. Rome remained relatively primitive until the 600s B.C., when the Etruscans, who controlled a series of city-states to the north, began taking control of the city. [Source: Jane von Mehren, National Geographic History, January 11, 2023]

By the sixth century B.C., some of Rome’s most famous institutions such as the Forum and the Senate existed. Sometime in the 6th century B.C. the leading Roman families were able to overthrew the Etruscan monarchs that ruled over them. According to one story, the Romans overthrew the Etruscans in 509 B.C. when the Etruscan king Superbus raped a virtuous Roman lady and the Roman populace responded by revolting. According to another account Etruscans domination ended when they were defeated by the Romans in a battle at Aricia south of Rome in 506 B.C. In any case the Roman republic was formed in 509 B.C. and the Etruscan monarchy collapsed around that the time.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Books: “Rome in the Late Republic” by Mary Beard and M Crawford, (2nd ed, Duckworth, 1999); “Et tu Brute: Caesar's Murder and Political Assassination” by G Woolf, (Profile Books, 2006); “Augustan Rome” by A Wallace-Hadrill, (Bristol Classical Press, Duckworth, 1998); “Cambridge Companion to Republican Rome” by H Flower (ed), (CUP, 2004); “Marcus Tullius Cicero, Select Letters” (Penguin, 2005)

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMULUS AND REMUS: STORIES, LEGENDS, ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY ROME: THE FIRST KINGS, NUMA, GOVERNMENT, WALLS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY ROMANS AND THE SABINES: RAPE, BATTLES AND UNIFICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMANS AND ETRUSCANS: INFLUENCES, BATTLES AND LEGENDARY KINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LAST THREE KINGS OF EARLY ROME: LEGENDS, ETRUSCAN ORIGINS, VIOLENCE, UPHEAVAL europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire” by Anthony Everitt (2013) Amazon.com;

“Early Rome to 290 BC: The Beginnings of the City and the Rise of the Republic” by Guy Bradley (2020) Amazon.com;

“Livy: The Early History of Rome, Books I-V” (Penguin Classics)

by Titus Livy , Aubrey de Sélincourt , et al. (2002) Amazon.com

“Romulus: The Legend of Rome's Founding Father” by Marc Hyden (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium” by Ross R. Holloway (2014) Amazon.com;

“Latium: Prelude to the Roman Kingdom” by Peter Tattersall (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium” by Ross R. Holloway (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Urbanisation of Rome and Latium Vetus: From the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era”

by Francesca Fulminante (2014), ebook Amazon.com;

"Italy Before Rome: A Sourcebook" (Routledge) by Katherine McDonald (2021) Amazon.com

“Central Italy: An Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric, Villanovan, Etruscan, Samnite, Italiote and Roman Remains and the Ancient Road Systems” by R. F. Paget (1973) Amazon.com;

“Italy Before the Romans: The Iron Age” by David Ridgway Amazon.com

“Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies” by Larissa Bonfante, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (1986) Amazon.com;

“Etruscans” by Graeme Barker, Tom Rasmussen (1998) Amazon.com;

“Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History” by Sybille Haynes (2005) Amazon.com;

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

"Roman Myths: Gods, Heroes, Villains and Legends of Ancient Rome” by Martin J Dougherty (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Romans: From Village to Empire” by Mary T. Boatwright , Daniel J. Gargola, et al. | Feb 26, 2004 Amazon.com;

“The Roman Conquest of Italy” by Jean-Michel David and Antonia Nevill (1996)

Amazon.com

“European Societies in the Bronze Age” by A. F. Harding (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age” by Anthony Harding and Harry Fokkens (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Pre-Roman Italy (1000–49 BCE) by Jane Botsford Johnson and Marco Maiuro (2024) Amazon.com;

“Production, Trade, and Connectivity in Pre-Roman Italy (Routledge) by Jeremy Armstrong and Sheira Cohen (2022) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

Creation of Rome from an Archaeological Perspective

According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: The urbanization of Rome could be inferred from the paving of the Forum and the removal of preceding huts around 650 B.C. to form a central and common space soon to be enlarged and surrounded by a growing number of stone buildings from 600 onward. A site adjacent to the Comitium paved with black stones (lapis niger) probably marked an open sanctuary to the god Vulcan. Another building that at least later on served as a cultic center, the Regia (king's palace), was built during the sixth century. It should be noted that Greek influence is visible in the arrangement of the central "political" space, as it is in archaeological details. The archaeological remnants of the earliest temples of the Forum Boarium (San Omobono), the cattle market on the border of the Tiber, are decorations by Greek artisans. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The most impressive testimony to early Rome's relation to the Mediterranean world dominated by the Greeks is the building project of the Capitoline temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (Jove the Best and Greatest), Juno, and Minerva, dateable to the latter part of the sixth century. By its sheer size the temple competes with the largest Greek sanctuaries, and the grouping of deities suggests that that was intended. The investment in the quality of the terracotta statuary points to the same intention. The actual size of the late-sixth-century city remains debated, but even as a larger city with international contacts, as shown by the treaty with Carthage, Rome was but one of the Latium townships. The conquests attributed to regal Rome in the Roman annalistic tradition were made up from a painful series of conflicts that ended with the Latin wars in 340 to 338 B.C. The Latin league was dissolved and the Latins were incorporated into the Roman community.

Parallel to the central investment of resources, the luxury of individual tombs — unlike in Etruscan centers — receded. Yet it would be erroneous to assume a highly centralized state. During republican times, even warfare was an enterprise frequently organized on a gentilician basis, as the institutions of the fetiales (legates that established the involvement or disinvolvement of the community as a whole into predatory conflicts) and the lapis Satricanus demonstrate. This dedicatory inscription from around 500 B.C., found at Satricum (northeast of Antium), accompanied a dedication to the warrior god Mars by followers (sodales) of a certain Poplios Valesius.

Rome and Romans Before the Roman Period

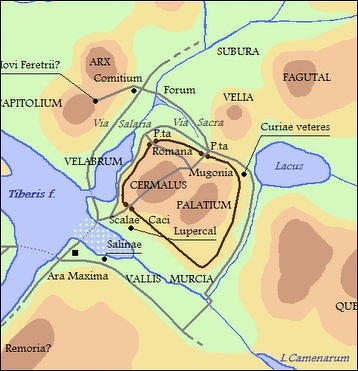

Rome in 753 BC

Archaeologists think Rome developed from a union of several hilltop villages after about the tenth century B.C., during the Iron Age. Before the Roman era the Romans were a subgroup of the larger Latin group, an Italic people that were primarily farmers who lived around present-day Rome. There was nothing particularly dominant or special about them. At the time other groups such as the Etruscans or Samnites seemed more likely to dominate the Italian peninsula than the Romans.

In the sixth century B.C., Rome was little more than a farming village of thatch huts on hills above the Tiber River occupied by three tribes with Etruscan names living under a king. Early Rome was ruled by the Etruscans. Rome’s last Etruscan king ascended to the throne in 535 B.C. The Romans threw him out in 509 and replaced the traditional monarchy with a republican government, blaming the king’s tyrannical behavior and holding it up as an example of the injustice of authoritarian rule.

The Romans from this era practiced a purifying ritual called Lupercalia. Priests sacrificed goats and a dog at the Lupercal, the cave where legend says Romolus and Remus were suckled, and their blood was smeared on two youths. Young women were whipped across their shoulders in the belief it bestowed fertility. The rite was performed in mid February at an altar near Lapis Niger, a sacred site paved with black stones near the Roman Forum until A.D. 494 when it was banned by the pope.

DNA Evidence on the Origin of the Romans and People in Italy

A 2019 genetic study published in the journal Science analyzed the autosomal DNA of 11 Iron Age samples from the areas around Rome, concluding that Etruscans (900-600 BC) and the Latins (900-200 BC) from Latium vetus were genetically similar, and Etruscans also had Steppe-related ancestry despite speaking a pre-Indo-European language. [Source Wikipedia]

A 2021 genetic study published in the journal Science Advances analyzed the autosomal DNA of 48 Iron Age individuals from Tuscany and Lazio and confirmed that the Etruscan individuals displayed the ancestral component Steppe in the same percentages as found in the previously analyzed Iron Age Latins, and that the Etruscans' DNA completely lacks a signal of recent admixture with Anatolia or the Eastern Mediterranean, concluding that the Etruscans were autochthonous and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors. Both Etruscans and Latins joined firmly the European cluster, 75 percent of the Etruscan male individuals were found to belong to haplogroup R1b, especially R1b-P312 and its derivative R1b-L2 whose direct ancestor is R1b-U152, while the most common mitochondrial DNA haplogroup among the Etruscans was H.

Legendary Period of Roman History

According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 B.C. upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 B.C., when the last king was overthrown. These kings ruled for an average of 35 years. The kings after Romulus were not known to be dynasts and no reference is made to the hereditary principle until after the fifth king Tarquinius Priscus. Consequently, some have assumed that the Tarquins and their attempt to institute a hereditary monarchy over this conjectured earlier elective monarchy resulted in the formation of the republic. [Source: Wikipedia]

Time Line for Legendary Period and Early Republic

753-716 Romulus Latin

Titus Tatius Sabine

715-673 B.C.: Numa Pompilius Sabine or Etruscan

674-642 B.C.: Tullus Hostilius Latin

642-617 B.C.: Ancus Marcius Sabine (partly)

616-579 B.C.: L. Tarquinius Priscus Etruscan/Greek

578-535 B.C.: Servius Tullius Latin or Etruscan

534-510 B.C.: Tarquinius Superbus Etruscan

[Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Annalists and the Legendary Period of Roman History

Annalists (from Latin annus, year) were a class of writers on Roman history, the period of whose literary activity lasted from the time of the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) to that of Sulla (139-78 B.C.). They generally wrote the history of Rome from the earliest — legendary — times down to their own time. Annalists differed from historians in that they were more likely to just record events for reference purposes, rather than offering their own opinions or insights into events. There is, however, some overlap between the two categories and sometimes annalist is used to refer to both styles of writing from the Roman era. [Source: Wikipedia]

Livy, the source of much of material from the legendary period of Rome

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “It is customary to begin any discussion of Early Rome with a discussion of the literary tradition. Modern writers on early Rome fall into two groups, broadly speaking: those who try to interpret the archaeological record in such a way as to be able to claim that there are kernels of truth in the annalistic tradition (Ogilvie is among these), and those who regard that attempt as fruitless and confine themselves to remarking on the archaeological record, believing in essence that nothing of what the classical writers have to say about pre-Republican Rome is true (e.g. Holloway). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“In one sense “the annalistic tradition” is used as a kind of shorthand to designate the works of T. Livius (Livy) and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Both of these were writers of the Augustan age. Both claimed to provide scholarly historical accounts stretching back to the foundation of the city of Rome by Romulus, an event which they believed had occurred some 700 years before their own day. How did information about a past so distant get down through the centuries to them? This, for the critical historian, is the crucial question to ask: what was the source, and how reliable was it? With ancient history, the ideal source is someone such as Thucydides or (on the Roman side) Polybius, who writes entirely or mostly about events which he himself has seen, or relies to the greatest extent possible upon eyewitnesses. ^*^

“Obviously that kind of method was impossible for someone in Livy's position, and he was well enough aware that what he was doing was not writing history in the Thucydidean mold. Rather, for each episode in the history of ancient Rome, he selected one or two from the available sources and rewrote their account (or cobbled them together if there were two), embellishing them liberally with speeches (for like Dionysius he was a rhetorician), and exercising only a minimum of critical judgement (understanding that to mean attempting to distinguish between truth and falsehood in the record of the past). Perhaps it is true, as Livy's modern champions such as Ogilvie and Walsh insist, that he brings a certain narrative genius to this task; but that is not germane to our present concern. As will become clear over the next few weeks, the inveterate weakness of the annalistic tradition is retrojection. Recent innovations were projected into the past in order to imbue them with the authority of early antiquity. Likewise, when the sources presented no filter or context in which to understand the few events from the regal period and the first century of the Republic which were recorded, the annalistic tradition responded by supplying one: namely, the struggle between the orders, the social and economic classes. ^*^

“The problems of reconciling the annalistic tradition with the archaeological evidence certainly do not end when we come to Servius Tullius. Timaeus of Tauromenium, the Sicilian annalist of the third century B.C., recorded that he had introduced coinage. But the archaeological record shows that earliest Campanian coins are not in use at Rome until the fourth century BC; earlier, the Roman currency was cattle and sheep for barter (the Latin word for money, pecunia, derives from pecus meaning 'herd') and aes rude, uncoined bronze ingots such as were found in the votive deposit, dated to the sixth century, associated with the paving over of the monuments covered by the lapis niger.” ^*^

Archaeology from the Legendary Period: Latin Cremators Versus Sabine Inhumers?

Palatine hut model

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Whether we call the inhabitants of Rome and the Alban hills in the early Iron Age southern Villanovans, or rather follow Holloway and insist that Latial culture develops directly from proto-Villanovan (that, in other words, there is no true Villanovan in Latium) is mainly a matter of terminology. These early Romans lived in circular huts, as the discovery of these post-holes from the Palatine show. The form of the huts is known from the hut-urns in which they buried their cremated dead, and these hut-shaped urns are a distinctive feature of this proto-Latial culture. The hut urns were found primarily in a cemetery in the Forum Romanum excavated by the great Italian archaeologist Boni in the early part of this century. The grave goods are characterized by miniaturization, as seen in this sketch of Forum Grave Y; the smaller vessels contained foodstuffs. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“From approximately the same time period, nearby on the Esquiline hill, there are a number of inhumations a fossa (in trenches, as opposed to the cremation burials a pozzo, in pits). The Corinthian olpe, dating to around 720 B.C. and inscribed with the name of its Greek owner, Ktektos, comes from one of these graves. The key question for the history of early Rome is whether the people who bury cremated remains in urns in the Forum Romanum are the same people as, or ethnically distinct from, the ones who practiced inhumation in graves on the Esquiline. ^*^

“One approach to this question, still popular today, is to say that the cremators were Latins, the inhumers Sabines. This argument points out that there are parallels for the inhumations to the south of Latium, and that later on in the Forum cemetery we get a combination of inhumation and cremation burials. This seems to indicate that two different peoples combined with one another, and recalls what the Romans believed happened in the time of Romulus, with the rape of the Sabine women and the subsequent commingling of the two peoples. A form of this approach appears in Ogilvie. ^*^

“A refinement of this hypothesis is given by Torelli (CAH 7.2). He suggests that after the two types begin to appear together, only "princes" are being buried in the cremation graves, because the cremation graves contain primarily the remains of adult males, with weapons. He also thinks that the hut-urn marks the deceased as a head of household, a paterfamilias. The burial practice would thus reflect an increasing degree of social stratification, consistent with the tradition of the kings. Torelli’s softer approach is reasonable. Increasing social stratification appears at the same time in neighboring Etruria (though not, apparently, in the houses which continue to be of uniform type into the 6th century), no doubt a reflection of Greek influence. But the whole idea that we have two distinct cultures combining in 8th century Rome has been called into question. The differences between the pottery and other objects in the graves on the Esquiline and in the Forum are subtle at best. It may be that they represent different time periods as opposed to different ethnic groups (see revised chronology). Finally, the presence of a few early cremations in hut urns on the Esquiline badly upsets the neatness of the scheme. It stems from the desire to rescue some shred of truth from the annalistic tradition on early Rome; but that desire, as we will see more fully next time, is hardly worthy of being fulfilled.

Oldest Temples in Rome

In 2014, archaeologists announced that the Romes-SantOmbono-Temple, dated to 7th-6th century B.C., contained the oldest known temple remains in Rome. Although the temple is one of the oldest in Rome it is not THE oldest. That honor goes to a temple that is under the Romes-SantOmbono-Temple. The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill is often described as the oldest Roman temple. It was built by the Etruscans on the Capitoline Hill, for Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. It was destroyed by fire three times. The first building, traditionally dedicated in 509 B.C., is been claimed to have been almost 60 × 60 meters (200 × 200 feet).

Jason M. Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The Sant’Omobono archaeological site in Rome isn’t much to behold. It is strewn with a seemingly haphazard array of stone blocks, walls, ditches, and the occasional column drum — hardly pleasing to the eye... So it’s not surprising that tourists on their way to better-known monuments scarcely give it a second look. [Source: Jason M. Urbanus, May-June 2014]

“In January 2014, however, the site suddenly received a great deal of attention when multiple international news sources reported incorrectly that Rome’s oldest temple had just been discovered there. As the archaeologists of the Sant’Omobono Project, an ongoing collaboration between the Superintendency of the Capitoline, the University of Calabria, and the University of Michigan, had actually made clear, this temple has been known — although rarely seen — since the 1930s, when it was first discovered.

“Beneath Sant’Omobono lies a series of religious buildings that defined the site for much of the first millennium B.C. The importance of this area, situated at a bend in the Tiber River and known as the Forum Boarium, or “cattle market,” stemmed from its location at the nexus of several ancient communication and trade routes. It was the economic center of early Rome, complete with the city’s earliest river harbor capable of providing a safe haven for ships, and an international marketplace where goods, as well as cultural ideas, religions, and languages, were exchanged. It was also a prime location for the construction of a temple to protect and oversee this activity. “The [Sant’Omobono] site is crucial for understanding the related processes of monumentalization, urbanization, and state formation in Rome in the late Archaic period,” says Dan Diffendale, a member of the University of Michigan team. The site’s main archaeological features are the twin temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta, which date to the late sixth or early fifth century b.c. Although these are among the oldest temple remains in ancient Rome, they actually sit atop an even older structure. This is the ancient Archaic period (roughly 800–500 B.C.) temple that January’s reports referred to.

This structure has been notoriously difficult to evaluate, because it lies deep beneath the ground, well below the city’s water table. Now, however, the Sant’Omobono Project has finally been able to get a glimpse at the early temple’s foundation. In order to achieve this, steel retaining walls were hammered into the ground to hold back the weight of the waterlogged soil, and mechanical pumps were then used to drain the trench. At a depth of more than fifteen feet, three courses of stone blocks belonging to the ancient temple were identified. “We were able for the first time to record the Archaic foundation with modern means, using total station and photogrammetry, as well as extensive photography,” says Diffendale. “This is the first time that the Archaic podium has been exposed in relatively dry condition.”

“In addition, the Sant’Omobono team was able to recover hundreds of artifacts, including votive offerings, drinking vessels, and figurines. These suggest that the temple dates to the late seventh and early sixth centuries B.C., making these the oldest known temple remains in Rome. For safety reasons, the trench could stay open for only three days before it was backfilled. Nevertheless, this latest round of work will have long-lasting effects on archaeologists’ study of the development and growth of the eternal city. The Sant’Omobono site has finally gained its rightful place in the spotlight as one of ancient Rome’s most important, even if least well known, sites.

Stories on the Founding of Rome

Aeneas flight from Troy

Plutarch wrote in A.D. 75: “From whom, and for what reason, the city of Rome, a name so great in glory, and famous in the mouths of all men, was so first called, authors do not agree. Some are of opinion that the Pelasgians, wandering over the greater part of the habitable world, and subduing numerous nations, fixed themselves here, and, from their own great strength in war, called the city Rome. Others, that at the taking of Troy, some few that escaped and met with shipping, put to sea, and driven by winds, were carried upon the coasts of Tuscany, and came to anchor off the mouth of the river Tiber, where their women, out of heart and weary with the sea, on its being proposed by one of the highest birth and best understanding amongst them, whose name was Roma, burnt the ships. With which act the men at first were angry. [Source: Plutarch. “Lives”, written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden]

“But afterwards, of necessity, seating themselves near Palatium, where things in a short while succeeded far better than they could hope, in that they found the country very good, and the people courteous, they not only did the lady Roma other honours, but added also this, of calling after her name the city which she had been the occasion of their founding. From this, they say, has come down that custom at Rome for women to salute their kinsmen and husbands with kisses; because these women, after they had burnt the ships, made use of such endearments when entreating and pacifying their husbands.

“Some again say that Roma, from whom this city was so called, was daughter of Italus and Leucaria; or, by another account, of Telaphus, Hercules's son, and that she was married to Aeneas, or, according to others again, to Ascanius, Aeneas's son. Some tell us that Romanus, the son of Ulysses and Circe, built it; some, Romus, the son of Emathion, Diomede having sent him from Troy; and others, Romus, king of the Latins, after driving out the Tyrrhenians, who had come from Thessaly into Lydia, and from thence into Italy.”

Founding of Rome According to Virgil’s Aeneid

Hanna Seariac wrote in the Deseret News: In Virgil’s “Aeneid” — a national epic poem sometimes considered propaganda, other times considered subversive — Virgil details the journey and war of the hero Aeneas. Exiled from Troy when the Hellenes pillaged and destroyed the city, Aeneas launches a voyage with his fleet to find a home. Juno, the goddess, tries to thwart him partially due to his dalliance with Queen Dido — the queen of Juno’s patron city Carthage.[Source: Hanna Seariac, Deseret News, April 22, 2023]

He arrives on the Sicilian shoreline and soon engages in battle with Turnus and his army. It’s said by different authors that Aeneas has two descendants, Romulus and Remus. Livy said Rhea Silvia, mother of Romulus and Remus, was a Vestal Virgin, who was assaulted by Mars. The wicked king Amulius put Romulus and Remus in a basket on the river Tiber.

A she-wolf raised them and they were eventually brought to a shepherd’s family. When the boys grew up, they killed Amulius and decided to start a city of their own. They used augury (oracle via birds) to decipher which hill to build the city upon — Remus saw six birds first, but Romulus saw 12. They disagreed on which one saw the divine sign. There are two variations of the story regarding what happened next.

Myth of Romulus and Remus

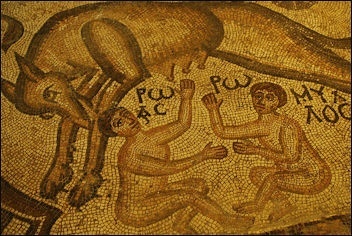

Romulus and Remus mosaic

According to the Roman legends, the origin of Rome was connected with Alba Longa, the first “city” of Latium, a region in central western Italy, occupied by Latins. The area had been inhabited since the Bronze Age by farming communities and was known to the ancient Greeks, which is perhaps why Aeneas, a Trojan prince, is said to have established it around 1150 B.C. [Source: Jane von Mehren, National Geographic History, January 11, 2023, Encyclopedia.com; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

The origin of Alba Longa was traced to the city of Troy in Asia Minor. After the fall of that famous city, it is said that the Trojan hero, Aeneas, fled from the ruins, bearing upon his shoulder his aged father, Anchises, and leading by the hand his son, Ascanius. Guided by the star of his mother, Venus, he landed on the shores of Italy with a band of Trojans, and was assured by omens that Latium was to be the seat of a great empire. He founded the city of Lavinium, and after his death his son Ascanius transferred the seat of the kingdom to Alba Longa. Here his descendants ruled for three hundred years, when the throne was usurped by a prince called Amulius. According to legend, in Alba Longa, Amulius and his brother Numitor fought over who would rule. Amulius triumphed, killing Numitor’s sons. To secure himself against any possible rivals, Amulius caused his brother’s daughter, Rhea Silvia, to take the vows of a vestal virgin.

Amulius wanted to make sure that Rhea Silvia had no children who would have a claim to the throne. Amulius beheaded Rhea Silvia. Even though Rhea Silvia was a vestal virgin she gave birth to Romulus and Remus. Their father, Mars, the god of war, raped here.

When Amulius found out about the twins, he ordered that they be thrown into the Tiber River to drown, but they remained under the guardianship of the gods and drifted in river unharmed, coming ashore near a sacred fig tree at the foot of the Palatine hill, located in modern-day Rome. A she-wolf and a woodpecker — creatures sacred to Mars — fed the twins and kept them alive until a shepherd named Faustulus found them. He and his wife adopted and raised the boys, who grew up to be brave and bold and perhaps not a little reckless and impetuous.

The twins became involved in local conflicts and led a group of youths on raids, including a raid on a herd of cattle that belonged to Numitor. Remus was caught and brought before Numitor. In questioning the young man, Numitor realized that Remus was his grandson. Shortly afterward, the twins led a revolt against Amulius. They killed him and put Numitor back on the throne.

See Separate Article: ROMULUS AND REMUS: STORIES, LEGENDS, ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

Romulus and Remus and the Creation of Rome

Romulus and Remus wanted to found a city of their own, so they returned to the place where Faustulus had discovered them and established the city of Rome on the banks of the Tiber River, where it was narrow enough for crossing and the hills provided a good defensive position. The land between the hills, however, was quite marshy and not all that fertile. The twins soon quarreled about the city’s exact boundaries. [Source: Jane von Mehren, National Geographic History, January 11, 2023, Encyclopedia.com; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901)]

An omen determined that Romulus should be the founder of the new city. He marked out the city boundaries and began to build a city wall. When Remus jumped over the unfinished wall, mocking his brother for thinking that it could keep anyone out of the city, Romulus killed him. Romulus became the sole leader of the new city, named Rome.

To populate Rome, Romulus, along with the outlaws and criminals he recruited, invited people who had fled from nearby areas to live there. However, most of these settlers were men. The city needed women. Romulus invited the Sabine people, who lived in neighboring towns, to come to Rome for a great festival. During the merriment Romulus raised his cloak signaling his men to seize and abduct the young Sabine women and drive the men from the city. This event became known as The Rape of the Sabine Women.

The Sabine men planned revenge and staged several small but unsuccessful raids. Then Titus Tatius, the Sabine king, led an army against Rome. The Romans were losing the battle when Romulus prayed to Jupiter, the king of the gods, for help. According to the Roman origin story being Roman wives suited the Sabine women and they could not bear to see their fathers and husbands killing one another. They stopped the Sabine men from battling the Romans when they came to recapture them. In the end, The two sides agreed to a peace in which the Sabines and Romans formed a union, with Rome as the capital.

Romulus ruled Rome for forty years. He disappeared mysteriously while reviewing his army on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) in a thunderstorm. Some legends indicate he ascended into the heavens, where he became the god Quirinus and sat alongside Jupiter, the king of the gods. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024