Home | Category: Science and Nature / Philosophy

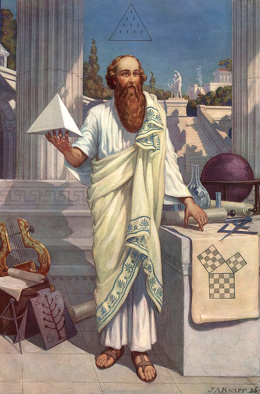

PYTHAGORAS

Pythagoras in Thomas Stanley's History of Philosophy

Pythagoras of Samos (sixth century B.C.) is said to have been the first man to call himself a philosopher and is credited with coining the word philosophy. None of his original writings survive. According to legend he fled the Aegean island of Samos as a youth to escape from an evil tyrant. After being exposed to new ideas in Egypt and Asia Minor he established a school in the Italian colony of Kroton in 530 B.C. After being persecuted and forced to flee again he settled in Metapontum, Greece, where he died around 500 B.C.

Pythagoras was one of the first people to become a vegetarian for health and philosophical reasons. He ate bread and honey for his meals, with vegetables for desert, and he even abstained from eating eggs and beans. He didn't eat meat because he believed that animals had souls. His belief about beans had nothing to do with farts. Instead it based on the belief that beans were the first offspring of the Earth.

There is no evidence that Pythagoras was a mathematician, let alone proved the theorem named after him or discovered the ratios of musical intervals. He was however a number-worshiper and a guru who founded a commune and spoke of the coming of a messiah-like figure. The theorem named after him (“the sum of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides”) was known to the Sumerians as early as 2000 B.C.

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

See Separate Articles:

PYTHAGOREANS AND THEIR STRANGE BELIEFS AND RULES factsanddetails.com

PYTHAGOREANS, MATH, MUSIC AND GEOMETRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY: HISTORY, PHILOSOPHERS, MAJOR SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Pythagoras: His Life and Teachings” by Thomas Stanley, James Wasserman, J. Daniel Gunther (2010) Amazon.com;

“Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans” by Charles H. Kahn (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings Which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy” by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie and David Fideler (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Harmony of the Spheres: The Pythagorean Tradition in Music” by Joscelyn Godwin | (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Pythagoreans: Digest (Rosicrucian Order) by Rosicrucian Order AMORC, Peter Kingsley, Ruth Phelps Amazon.com;

“The Manual of Harmonics of Nicomachus the Pythagorean” by Nicomachus of Gerasa and Flora R. Levin (1993) Amazon.com;

“On the Pythagorean Way of Life [Iamblichus]: Text, Translations, and Notes (English, Ancient Greek) by Iamblicus, John M. Dillon (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition”

by Peter Kingsley (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metaphysics of the Pythagorean Theorem: Thales, Pythagoras, Engineering, Diagrams, and the Construction of the Cosmos out of Right Triangles” by Robert Hahn (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Music” by M. L. West (1994)

Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece: Melody, Rhythm and Life” (Classical World)

by Spencer A. Klavan (2021) Amazon.com;

“Mode in Ancient Greek Music” (Cambridge Classical Studies)

by R. P. Winnington-Ingram (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Science” by Liba Taub (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean”

by Victor J. Katz and Clemency Montelle (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World” by Charles Freeman (2000) Amazon.com;

“Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle” by G. E. R. Lloyd (1974) Amazon.com;

Pythagoras as a Legendary Figure

Pythagoras was a cult leader who was hailed as a deity and believed in reincarnation, It has also been claimed that he was a murderer who could talk to animals, predict the future, and heal “pestilences.” On top of this he had an over-the-top aversion to beans. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: While he is famous to us for his mathematical theorems, in antiquity Pythagoras was renowned for the philosophical-religious sect that he founded. His sheer popularity means that there are numerous legends and traditions about his life, but the basic story goes something like this. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

According to Dicaearchus, a one-time pupil of Aristotle,Pythagoras was tall, attractive, and alluring. He had a natural charisma that was heightened by his unusual style of dress: he wore a white robe over white trousers and accessorized with a golden wreath. This (admittedly fierce) look was probably supposed to draw comparisons with Orpheus. The most unique facet of his appearance, however, was his mysterious “golden thigh.” It’s unclear exactly what this was — a birthmark? thigh jewelry? — but its reputation led some to speculate that his leg was composed entirely of metal. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

According to the admiring biographies written hundreds of years later, he was able to communicate with animals, St. Francis of Assisi-style. He domesticated an aggressive bear and persuaded her to refrain from attacking other animals; he persuaded an ox into forgoing a diet of beans (the ox agreed and retired to the Temple of Hera to live out its days as a sacred animal); and he was known to receive divine messages from the gods. These would be communicated using the language of the universe: through omens, flights of birds, and secret signs. Some say that he could converse with rivers, predict the future, and even bilocate. Two of his biographers, Porphry and Iamblicus, report that he was spotted on the same day in both Metapontum in Italy and Tauromenium in Sicily (The cities were several days travel apart).

Pythagoras’s Early Life

Pythagoras was born on the Greek Island of Samos (or possibly Tyre in Lebanon or the Island of Lemnos) around 570 B.C., to a woman named Pythais. Though some claimed he was the progeny of the god Apollo, his father, Mnesarchos, was either a gem engraver or a grain trader who became a citizen of Samos. It is believed that Pythagoras passed his early manhood at Samos and "flourished," we are told, in the reign of Polycrates (532 B.C.). This date cannot be far wrong; for Heraclitus already speaks of him in the past tense.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In either case, at the age of 18 Pythagoras left Samos to begin his travels to broaden his education. He studied natural history (and probably also math) with Thales and Anaximander in the Mediterranean coastal city Miletus, Homeric Poetry with Hermodamas, and cosmology (physics) with Pherecydes of Syros. He did his best learning, however, while journeying further abroad. In what is a bit of an ancient biographical cliché, he visited Egypt and earned the respect of the priests. Eventually, after winning their trust, he was initiated into Egyptian religious rituals. He also picked up some geometry. During his travels in southwest Asia, he acquired a knowledge of arithmetic from the Phoenicians and astronomy from the Chaldeans. A second century B.C. romance writer reports that he learned the art of dream interpretation from ancient Jews, and other sources allege that he traveled as far afield as India, Northern France, and Spain. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

The extensive travels attributed to Pythagoras by late writers are, of course, apocryphal. Even the statement that he visited Egypt, though far from improbable if we consider the close relations between Polycrates of Samos and Amasis, rests on no sufficient authority. Herodotus, it is true, observes that the Egyptians agreed in certain practices with the rules called Orphic and Bacchic, which are really Egyptian, and with the Pythagoreans; but this does not imply that the Pythagoreans derived these directly from Egypt. He says also that the belief in transmigration came from Egypt, though certain Greeks, both at an earlier and a later date, had passed it off as their own. He refuses, however, to give their names, so he can hardly be referring to Pythagoras. Nor does it matter; for the Egyptians did not believe in transmigration at all, and Herodotus was deceived by the priests or the symbolism of the monuments. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

Pythagoras Found a Philosophical School

Aristoxenus said that Pythagoras left Samos in order to escape from the tyranny of Polycrates. It was at Croton, a city which had long been in friendly relations with Samos and was famed for its athletes and its doctors, that he founded his philosophical school. Timaeus appears to have said that he came to Italy in 529 B.C. and remained at Croton for twenty years. He died at Metapontum, where he had retired to when the Crotoniates rose in revolt against his authority. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Having acquired so much learning and with a great deal of innate supernatural skill, Pythagoras returned home to Samos where he founded his own philosophical school in a cave outside the city. According to one biographer, the best minds in Greece came to Samos to learn his mathematically informed astronomy. He may have moonlighted as an athletics instructor, but it’s more likely that the ancient wrestling coach simply had the same name. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

At the age of 40 (one suspects in the throes of a midlife crisis) he emigrated to Croton, where in a series of charismatic speeches he won over the local population. His practical philosophy was filled with the kind of advice that was unobjectionable: manage your household well, don’t abuse the gods, protect familial structures, and so on. Some of it, for instance the instruction not to sleep with people other than one’s wife, was pretty innovative for the time. This particular teaching, legend says, was sparked by a trip to the underworld in which he saw adulterers being punished.

He also began to teach people about the characteristics of what philosophers call “the good life.” For his most devoted followers the price of discipleship was high. They lived in a commune, shared possessions, lived on a sparse vegetarian diet, and avoided alcohol. So far, so normal: These are the habits of your run-of-the-mill monastic group or modern-day wellness retreat. But Pythagoreans did more than this: they never traveled on the high road; they always wore white but never touched white roosters, and they had specific instructions about the order in which clothes should be put on (right shoe first, if you were wondering).

Pythagoras and Beans

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Perhaps the strangest is that they also avoided eating fava beans entirely. This, after all, was the subject of Pythagoras’s conversation with the ox. Ancient opinion is divided about the logic behind the prohibition. One view maintained that beans made one fart and there was a risk that one would flatulate one’s airy ethereal soul. Another, recorded by the Roman writer Pliny, hypothesized that the beans themselves were “ensouled” on account of their flesh-like texture. A fragment of Aristotle presents a cluster of explanations stating that, “he warned people to abstain from beans, either because they resembled genitals, or the gates of Hades (for it is the only plant without joints), or because it is harmful or because it resembles the nature of the universe or because it is [not] oligarchical.” If you have some questions about this last one, you are not alone. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

To be fair to Pythagoras, it is worth noting that fava beans were a sticking point for many ancient religious orders. As Christopher Riedwig discusses in his book Pythagoras: His Life, Teaching and Influence, seers and priests in both Greece and India had to abstain from eating fava beans before participating in religious ceremonies. Moreover, “favism,” the genetic food allergy in which sufferers can have a serious response to fava beans is more prevalent in Mediterranean countries.

The taboo, as Riedwig argues, seems to stem from the idea of ensoulment and reincarnation. Pythagoras believed in the transmigration of souls after death. The ancient saying that “eating beans and eating the heads of one’s parents amounts to the same thing” was attributed both to Orpheus and to Pythagoras. Pythagoras certainly did believe in the transmigration of souls into new bodies at death and, as such, this explanation makes a certain amount of sense.

Pythagoras Cult and Stories About It

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Pythagoras was stunningly popular and commanded devotion from a large following who revered him as a god. Those in his inner circle would use secret mathematical reflections and philosophy as a form of divine contemplation. Think meditation but with mathematics. Numbers were the building blocks of the universe and numerical mysticism was the pathway to unity with the divine. With such high stakes, initiates into this process were required to maintain the highest moral standards. As Margaret Wethem puts it in her book Pythagoras’s Trousers, her believed “that mathematics should be revealed only to those who had been properly purified in both mind and body.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

For those who broke his triangle of trust, however, the penalty was allegedly high. One follower, Hippasus of Metapontum, was rumored to have revealed one of the secret symbols — a pentagonal dodecahedron — and subsequently drowned in the sea because of his apostasy. A different version of story, attributed to fourth century A.D. mathematician Pappus of Alexandria and popular among modern mathematicians, alleges that Hippasus had discovered irrational numbers and was drowned by Pythagoras himself for revealing the secret. But, as classicist Peter Gainsford explains, there’s no evidence that this happened. The stories about murder and divine retribution originated in a symbolic practice in which those who apostatized from the community were mourned as if they were dead. The ritual included the construction of a burial mound and erection of a gravestone, which feels extra.

Though an ancient saying claimed that “among rational creatures there are gods and men and beings like Pythagoras,” Pythagoras was mortal. Though there are numerous contradictory stories about his death it is clear that not everyone appreciated his brand of philosophy, and many saw him as a charlatan or social revolutionary. According to Dicaerchus, whose words are filtered through later authors, after causing revolts and being exiled from a number of Greek cities Pythagoras ended his days as a fugitive in the Temple of the Muses at Metapontum. The cause of death was forty days of starvation. A more sensational version relays that his commune was attacked by the henchmen of a local aristocrat and burned to the ground. His disciples formed a human ladder to permit him to escape the flames. Pythagoras was pursued on foot but came to a halt at a field of fava beans. Unwilling to compromise his principles he stood there, was caught, and killed. The beans, presumably, survived.

The difficulty with these legends — especially those about his miraculous abilities and godlike countenance — is that the primary sources for them disagree with one another and were written down roughly 500-700 years after the events. Porphyry of Tyre and Iamblichus of Chalcis, Pythagoras’s chief biographers, lived in the third century A.D. Hundreds of years of history, mathematical and philosophical thinking, and popular mythological trends cloud the issues. The Pythagoras of Iamblichus’s Life looks eerily like Jesus. This is hardly accidental: The Pythagoras of history is impossible to see through the fog.

Pythagoras as a Man of Science and Philosophy

John Burnet wrote with all this " we should be tempted to delete the name of Pythagoras from the history of philosophy, and relegate him to the class of "medicine-men" (goêtes) along with Epimenides and Onomacritus. That, however, would be quite wrong. The Pythagorean Society became the chief scientific school of Greece, and it is certain that Pythagorean science goes back to the early years of the fifth century, and therefore to the founder. Heraclitus, who is not partial to him, says that Pythagoras had pursued scientific investigation further than other men. Herodotus called Pythagoras "by no means the weakest sophist of the Hellenes," a title which at this date does not imply the slightest disparagement, but does imply scientific studies. Aristotle said that Pythagoras at first busied himself with mathematics and numbers, though he adds that later he did not renounce the miracle-mongering of Pherecydes. Can we trace any connection between these two sides of his activity? [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

“We have seen that the aim of the Orphic and other Orgia was to obtain release from the "wheel of birth" by means of "purifications" of a primitive type. The new thing in the society founded by Pythagoras seems to have been that, while it admitted all these old practices, it at the same time suggested a deeper idea of what "purification" really is. Aristoxenus said that the Pythagoreans employed music to purge the soul as they used medicine to purge the body. Such methods of purifying the soul were familiar in the Orgia of the Korybantes, and will serve to explain the Pythagorean interest in Harmonics. But there is more than this. If we can trust Heraclides, it was Pythagoras who first distinguished the "three lives," the Theoretic, the Practical, and the Apolaustic, which Aristotle made use of in the Ethics.

The doctrine is to this effect. We are strangers in this world, and the body is the tomb of the soul, and yet we must not seek to escape by self-murder; for we are the chattels of God who is our herdsman, and without his command we have no right to make our escape. In this life there are three kinds of men, just as there are three sorts of people who come to the Olympic Games. The lowest class is made up of those who come to buy and sell, and next above them are those who come to compete. Best of all, however, are those who come to look on (theorein). The greatest purification of all is, therefore, science, and it is the man who devotes himself to that, the true philosopher, who has most effectually released himself from the "wheel of birth." It would be rash to say that Pythagoras expressed himself exactly in this manner; but all these ideas are genuinely Pythagorean, and it is only in some such way that we can bridge the gulf which separates Pythagoras the man of science from Pythagoras the religious teacher. It is easy to understand that most of his followers would rest content with the humbler kinds of purification, and this will account for the sect of the Akousmatics. A few would rise to the higher doctrine, and we have now to ask how much of the later Pythagorean science may be ascribed to Pythagoras himself.

Accounts by Other Philosophers on Pythagoras

Pythagoras in Raphael's School of Athens

“It is not easy to give any account of Pythagoras that can claim to be regarded as historical. The earliest reference to him, indeed, is practically a contemporary one. Some verses are quoted from Xenophanes, in which we are told that Pythagoras once heard a dog howling and appealed to its master not to beat it, as he recognized the voice of a departed friend. From this we know that he taught the doctrine of transmigration. Heraclitus, in the next generation, speaks of his having carried scientific investigation (historiê) further than any one, though he made use of it for purposes of imposture. Later, though still within the century, Herodotus speaks of him as "not the weakest scientific man (sophistês) among the Hellenes," and he says he had been told by the Greeks of the Hellespont that the legendary Scythian Salmoxis had been a slave of Pythagoras at Samos. He does not believe that; for he knew Salmoxis lived many years before Pythagoras. The story, however, is evidence that Pythagoras was well known in the fifth century, both as a scientific man and as a preacher of immortality. That takes us some way. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

“Plato was deeply interested in Pythagoreanism, but he is curiously reserved about Pythagoras. He only mentions him once by name in all his writings, and all we are told then is that he won the affections of his followers in an unusual degree (diapherontôs êgapêthê) by teaching them a "way of life," which was still called Pythagorean. Even the Pythagoreans are only once mentioned by name, in the passage where Socrates is made to say that they regard music and astronomy as sister sciences. On the other hand, Plato tells us a good deal about men whom we know from other sources to have been Pythagoreans, but he avoids the name. For all he says, we should only have been able to guess that Echecrates and Philolaus belonged to the school. Usually Pythagorean views are given anonymously, as those of "ingenious persons" (kompsoi tives) or the like, and we are not even told expressly that Timaeus the Locrian, into whose mouth Plato has placed an unmistakably Pythagorean cosmology, belonged to the society. We are left to infer it from the fact that he comes from Italy. Aristotle imitates his master's reserve in this matter. The name of Pythagoras occurs only twice in the genuine works that have come down to us. In one place we are told that Alcmaeon was a young man in the old age of Pythagoras, and the other is a quotation from Alcidamas to the effect that "the men of Italy honored Pythagoras." Aristotle is not so shy of the word "Pythagorean" as Plato, but he uses it in a curious way. He says such things as "the men of Italy who are called Pythagoreans," and he usually refers to particular doctrines as those of "some of the Pythagoreans." It looks as if there was some doubt in the fourth century as to who the genuine Pythagoreans were. We shall see why as we go on.

“Aristotle also wrote a special treatise on the Pythagoreans which has not come down to us, but from which quotations are found in later writers. These are of great value, as they have to do with the religious side of Pythagoreanism.

“The only other ancient authorities on Pythagoras were Aristoxenus of Taras, Dicaearchus of Messene, and Timaeus of Tauromenium, who all had special opportunities of knowing something about him. The account of the Pythagorean Order in the Life of Pythagoras by Iamblichus is based mainly on Timaeus, who was no doubt an uncritical historian, but who had access to information about Italy and Sicily which makes his testimony very valuable when it can be recovered. Aristoxenus had been personally acquainted with the last generation of the Pythagorean society at Phlius. It is evident, however, that he wished to represent Pythagoras simply as a man of science, and was anxious to refute the idea that he was a religious teacher. In the same way, Dicaearchus tried to make out that Pythagoras was simply a statesman and reformer.

“When we come to the Lives of Pythagoras, by Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Diogenes Laertius, we find ourselves once more in the region of the miraculous. They are based on authorities of a very suspicious character, and the result is a mass of incredible fiction. It would be quite wrong, however, to ignore the miraculous elements in the legend of Pythagoras; for some of the most striking miracles are quoted from Aristotle's work on the Pythagoreans and from the Tripod of Andron of Ephesus, both of which belong to the fourth century B.C., and cannot have been influenced by Neopythagorean fancies. The fact is that the oldest and the latest accounts agree in representing Pythagoras as a wonder-worker; but, for some reason, an attempt was made in the fourth century to save his memory from that imputation. This helps to account for the cautious references of Plato and Aristotle, but its full significance will only appear later.

Philolaus, the Man Who Carried on Pythagoras’s Teachings

Pythagoras and Philolaus

Philolaus (470-ca. 385 B.C.) of Croton, in southern Italy — a Greek philosopher-scientist and contemporary of Socrates — was one of the main articulators of Pythagorean teachings. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “He is one of the three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition, born a hundred years after Pythagoras himself and fifty years before Archytas. He wrote one book, On Nature, which was probably the first book to be written by a Pythagorean. There has been considerable controversy concerning the 20+ fragments which have been preserved in Philolaus' name. It is now generally accepted that some eleven of the fragments come from his genuine book.”

It seems natural to suppose that the Pythagorean elements of Plato's Phaedo and Gorgias come mainly from Philolaus. Plato makes Socrates express surprise that Simmias and Cebes had not learnt from him why it is unlawful for a man to take his life, and it seems to be implied that the Pythagoreans at Thebes used the word "philosopher" in the special sense of a man who is seeking to find a way of release from the burden of this life. It is probable that Philolaus spoke of the body (sôma) as the tomb (sêma) of the soul. We seem to be justified, then, in holding that he taught the old Pythagorean religious doctrine in some form, and that he laid special stress on knowledge as a means of release. That is the impression we get from Plato, who is far the best authority we have. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

“We know further that Philolaus wrote on "numbers"; for Speusippus followed him in the account he gave of the Pythagorean theories on that subject. It is probable that he busied himself mainly with arithmetic, and we can hardly doubt that his geometry was of the primitive type described in an earlier chapter. Eurytus was his disciple, and we have seen that his views were still very crude.

“We also know now that Philolaus wrote on medicine, and that, while apparently influenced by the theories of the Sicilian school, he opposed them from the Pythagorean standpoint. In particular, he said that our bodies were composed only of the warm, and did not participate in the cold. It was only after birth that the cold was introduced by respiration. The connection of this with the old Pythagorean theory is clear. Just as the Fire in the macrocosm draws in and limits the cold dark breath which surrounds the world, so do our bodies inhale cold breath from outside. Philolaus made bile, blood, and phlegm the causes of disease; and, in accordance with this theory, he had to deny that the phlegm was cold, as the Sicilian school held. Its etymology proved it to be warm. We shall see that it was probably this preoccupation with the medicine of the Sicilian school that gave rise to some of the most striking developments of later Pythagoreanism.

Influences and Legacy of Pythagoras

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: There’s no doubting the extent of Pythagoras’s influence. His ideas about musicology, astronomy, geometry, and arithmetic had influenced 2500 years of subsequent scientific and mathematical speculation. Everyone from Copernicus, to Fibonacci, to Kepler and even Albert Einstein have been shaped by his ideas. At several moments throughout history, he has become the poster child for vegetarianism and an inspiration for literary giants Chesterfield, Shelley, and Tolstoy. Even the structures of the heavenly and hellish worlds in Dante’s Divine Comedy were based on Pythagorean numbers. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 18, 2022]

Ironically, however, the contribution for which he is best known — the Pythagorean Theorem — is not his own discovery. The Babylonians were using it a thousand years before he was born. What might seem most alien to us, however, is that, for Pythagoras, mathematics was less about practical worldly affairs than it was about understanding and communicating with the transcendent.

However, John Burnet writes, “Of the opinions of Pythagoras we know even less than of his life. Plato and Aristotle clearly knew nothing for certain of ethical or physical doctrines going back to the founder himself. Aristoxenus gave a string of moral precepts. Dicaearchus said hardly anything of what Pythagoras taught his disciples was known except the doctrine of transmigration, the periodic cycle, and the kinship of all living creatures. Pythagoras apparently preferred oral instruction to the dissemination of his opinions by writing, and it was not till Alexandrian times that anyone ventured to forge books in his name. The writings ascribed to the first Pythagoreans were also forgeries of the same period. The early history of Pythagoreanism is, therefore, wholly conjectural; but we may still make an attempt to understand, in a very general way, what the position of Pythagoras in the history of Greek thought must have been. [Source: John Burnet (1863-1928), “Early Greek Philosophy” London and Edinburgh: A. and C. Black, 1892, 3rd edition, 1920, Evansville University ]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024