Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

TEACHERS IN ANCIENT GREECE

Teachers, in most cases, were either educated slaves or tutors hired out for a fee. Most children began their studies at age seven. but there were no strict rules governing when a child's schooling began or how long it should last.

The salary which the teacher or tutor received for his instruction probably depended on his knowledge and ability; doubtless popular teachers were well paid. But it was not a paying profession, for it is not likely that the school fees, usually paid monthly, were high; also negligent fathers often put off paying them for a long time; while stingy parents kept their children at home during a month in which there were many holidays, in order to save the school fees. We must not assume high culture in these elementary teachers, and we find that the pupils feared their masters more than they loved them, which is natural, seeing that they seem to have made a freer use of canes and sticks than our present pedagogic principles would permit. Still we do not find any Greek pendant to Horace’s Plagosus Orbilius. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

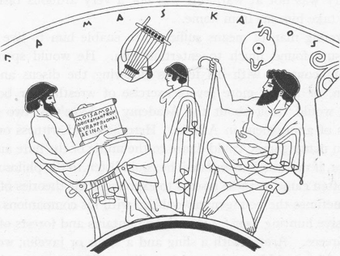

Masters and pupils are dressed alike, wearing only the himation. It is important, however, to remember that this dress on the monuments by no means corresponds to reality, and, as a rule, the chiton cannot have been wanting under the himation. The masters, some of whom are young and beardless, others more advanced in age, sit on simple stools; with the exception of one pupil, who is learning the lyre, the boys stand upright before them, both arms wrapped in their cloaks, as was considered fitting for well-bred youths. Of course, the boy with the lyre must have the upper part of his body free, and his himation is folded over his knee. There is a difference of opinion as to the two bearded men leaning on their sticks, who are present at these scenes, and attentively looking on; it has been suggested that they are paidagogoi, who have accompanied the boys to school, and are superintending them during the instruction; or else, on account of the manner in which they are sitting, it has been assumed that they are fathers or inspectors.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EDUCATION IN ANCIENT GREECE factsanddetails.com ;

SCHOOLS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CURRICULUM AND SUBJECTS TAUGHT IN ANCIENT GREEK SCHOOLS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History Of Education In Antiquity” by H.I. Marrou and George Lamb (1982) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Education” by Robin Barrow (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Education: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Mark Joyal , J.C Yardley, et al. (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World” by Judith Evans Grubbs and Tim Parkin (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education & Culture in Ancient Sparta” by Nigel M. Kennell (1995) Amazon.com;

“School in Ancient Greece” by Dimitris Pandermalis (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gymnastics of the Mind: Greek Education in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt”

by Raffaella Cribiore (2005) Amazon.com;

“Plato's Academy Annotated Edition” by Paul Kalligas Amazon.com;

“Rhetoric to Alexander” (Illustrated) by Aristotle and Aeterna Press (2015), of dubious origin Amazon.com;

“Libraries in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“Writing Greek: An Introduction to Writing in the Language of Classical Athens”

by John Taylor and Stephen Anderson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mathematics: History of Mathematics in Ancient Greece and Hellenism”

by Dietmar Herrmann (2023) Amazon.com;

“Mathematics in Ancient Greece (Dover Books) by Tobias Dantzig (2012) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Athens: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins (1986) Amazon.com;

“Greek Realities: Life and Thought in Ancient Greece” by Finley P. Hooper (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Methods of School Instruction in Ancient Greece

Instruction usually began early in the morning; we do not know how long it lasted, but there certainly were lessons given in the afternoon; an ordinance of Solon’s forbade their continuance after sunset. We do not know how the elementary and gymnastic instruction were combined. There were plenty of holidays, owing to the numerous feasts and festivals; there were also special school festivals, especially those of the Muses for the grammar schools, and of Hermes for the gymnasia. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

the gymnasium at Olympia

A very interesting picture by the vase painter Duris gives us, in spite of some artistic liberties, an excellent idea of Attic school teaching in the fifth century B.C. The scenes are represented on the outside of a bowl; on each half five people are depicted: two masters, two pupils, and an oldish man looking on. This cannot, therefore, represent one of the ordinary schoolrooms, where a single master instructs together a whole class of boys, for each boy is being instructed by a separate teacher. Perhaps this is a liberty on the part of the painter, who has grouped together four separate scenes, or else this individual instruction may really have taken place even in the public schools.

The subjects taught here all belong to musical instruction (that is, instruction over which the Muses preside), and are partly concerned with grammatical teaching, partly with actual teaching of music. On one side we see a young teacher playing the double pipe, while the boy standing in front of him listens attentively. It is usually assumed that the boy is learning to play the flute, but then it is curious that he has not an instrument in his own hands, like the boy who is learning the lyre; for if he wished to imitate what the teacher is showing him, he would have to take the master’s instrument. There is something, therefore, to be said for the hypothesis that the boy is learning to sing, and the master is giving him on the flute the notes or the melody which he has to sing. The scene on the right of this represents instruction in writing. The boy stands in the same position as the other, before another young teacher, who holds a triptych consisting of three little folding tablets, open before him, and has a pencil in his right hand. He is looking attentively at the tablet, either correcting the boy’s writing or about himself to write a copy for the pupil. On the other side of the picture we have, on the left, musical instruction. Both master and pupil have seven-stringed lyres in their hands; at the moment represented the master seems to be only showing the boy how to grasp the chords by the fingers of the left hand, and is making no use of the rod, which he holds in his right. The boy, who sits bent forward, is trying to imitate the master’s action. The last group represents a pupil who appears to be reciting a poem, the beginning of which is written on the scroll which the master holds in his hand.

Teachers, Officials and Trainers at Gymnasia

Ephebi describes were adolescent male students. They received their gymnastic instruction, or practised on their own account, at a gymnasium. The superintendence of the youths who practised here, and the maintaining of order were the duty of the Gymnasiarchs. They had the right of discipline, which they could exercise on any visitor to the gymnasium, and in token of this they carried a rod; thus we often see on vase pictures, among the gymnasts, men with long sticks, probably meant to represent the gymnasiarchs. In the older period at Athens there was but one gymnasiarch, but afterwards several shared the dignity. We cannot decide how far they also exercised a right of control over the wrestling-schools. Besides the gymnasiarch, or perhaps below him, was a board of officials whose duty it was to see to the preservation of the buildings and of the implements used in the gymnasia, while the general superintendence of the athletic exercises, and therefore also of the gymnasia, was exercised by the superintendents mentioned above, and, as a rule, men somewhat advanced in years were chosen for these posts. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

A hermaic sculpture of an old man, thought to be the master of a gymnasium., based partly on thelong stick in his right hand, from Ai Khanoum, Afghanistan, 2nd century BC

There were other officials who were not so much concerned with the external arrangements of the gymnasia as with the instruction given there. The president of the gymnasium and head of the teachers is not mentioned until the late Hellenic and Roman periods; under him were the actual teachers and also those who instructed the ephebi in grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy; but in the classic period no instruction of this kind was given. At that time, however, we find the trainer acting as gymnastic teacher to the older youths, whose aim was to prepare themselves for athletic contests, and who intended to enter the lists as professional athletes. As boys were sometimes prepared for such contests, no doubt the trainer sometimes took the place of the ordinary teacher; and again, on the other hand, a competent gymnastic master sometimes undertook the training of athletes. Generally speaking, however, in the older period this distinction was maintained, that the boys’ teacher was concerned chiefly with the general training of the body suitable for everyone, and wrestling on a rational and hygienic basis, while the trainer was a professional teacher, and was more concerned with special subjects than the general harmonious development of the body. Below these teachers stood the rubber, whose task was originally a purely mechanical one, but gradually when anointing and rubbing came to be regarded from the hygienic point of view, and were perhaps connected with a kind of massage, his standing improved, and after a time he took a far more important position than belonged to him of right.

In spite of the numerous allusions to the instruction of the ephebi which have come down to us, there is a good deal that is still doubtful or unexplained; as, for instance, in how far the trainers also instructed those ephebi who were not in training for the contests, and whether they were paid for their services by the State or by each pupil individually. Afterwards, at any rate, the ephebi as a rule only paid a fee to the teacher for musical instruction, while the gymnastic teacher seems to have been paid by the State.

Male Mentor-Student Relationship in Ancient Greece

Ward Hazell wrote in Listverse: In ancient Greece, it was customary for an adult male to take a young Greek boy as a protege, or eromenos. In order for a young Greek citizen to progress in society, it was necessary to have a mentor. There was sometimes a sexual aspect to this relationship. Some scholars believe that pederastic practices originated in Dorian initiation rites, though there do appear to have been some conventions about the proper way to conduct these relationships. [Source Ward Hazell, Listverse, August 31, 2019]

The adult man was to always be the dominant partner, and the relationship was to cease when the eromenos grew a beard, thus signifying his adulthood. Sexual relations between adult men were not considered dignified. Adult men in Greece took citizenship seriously and would enlighten their proteges in all the ways of the world, which sometimes, but not always, included sex. Sexuality in ancient Greece was not considered in terms of relationships but only in terms of desire, or aphrodisia, which might overpower them at any moment.

The eromenos was assessed during his period of patronage for his potential to assume civic responsibilities. If the older male refrained from having sex with the eromenos, it was considered to be a mark of respect for the boy’s status, as well as a sign of powerful self-control in the adult, which was good for both of them. However, should the adult lack self-control, the eromenos was expected to comply with any “requests” out of gratitude and respect, as well as the prospect of a lifelong career.

Plutarch: The Training of Children

Plutarch was born of a wealthy family in Boeotia at Chaeronea in Greece about 50 A.D. Part of his life seems to have been spent at Rome, but he seems to have returned to Greece and died there about 120 A.D. But little further is know of his life. He was one of the greatest biographers the world has ever known, while his moral essays show wide learning and considerable depth of contemplation. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “1. The course that ought to be taken for the training of freeborn children, and the means whereby their manners may be rendered virtuous, will, with the reader's leave, be the subject of our present disquisition. 2. In the management of which, perhaps it may be expedient to take our rise from their very procreation. I would therefore, in the first place, advise those who desire to become the parents of famous and eminent children, that they keep not company with all women that they light on; I mean such as harlots, or concubines. For such children as are blemished in their birth, either by the father's or the mother's side, are liable to be pursued, as long as they live, with the indelible infamy of their base extraction, as that which offers a ready occasion to all that desire to take hold of it of reproaching and disgracing them therewith. “Misfortune on that family's entailed,/ Whose reputation in its founder failed.”

“Wherefore, since to be well-born gives men a good stock of confidence, the consideration thereof ought to be of no small value to such as desire to leave behind them a lawful issue. For the spirits of men who are alloyed and counterfeit in their birth are naturally enfeebled and debased; as rightly said the poet again — “A bold and daring spirit is oft daunted,/ When with the guilt of parents' crimes 'tis haunted.

“So, on the contrary, a certain loftiness and natural gallantry of spirit is wont to fill the breasts of those who are born of illustrious parents. Of which Diaphantus, the young son of Themistocles, is a notable instance; for he is reported to have made his boast often and in many companies, that whatsoever pleased him pleased also all Athens; for whatever he liked, his mother liked; and whatever his mother liked, Themistocles liked; and whatever Themistocles liked, all the Athenians liked. Wherefore it was gallantly done of the Lacedaemonian states, when they laid a round fine on their king Archidamus for marrying a little woman, giving this reason for their so doing: that he meant to beget for them not kings, but kinglings.

“3. The advice which I am, in the next place, about to give, is, indeed, no other than what has been given by those who have undertaken this argument before me. You will ask me what is that? It is this: that no man keep company with his wife for issue's sake but when he is sober, having drunk either no wine, or at least not such a quantity as to distemper him; for they usually prove wine-bibbers and drunkards, whose parents begot them when they were drunk. Wherefore Diogenes said to a stripling somewhat crack-brained and half-witted: Surely, young man, your father begot you when he was drunk. Let this suffice to be spoken concerning the procreation of children; and let us pass thence to their education.

Plutarch on Teaching Virtue and Morality

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “4. And here, to speak summarily, what we are wont to say of arts and sciences may be said also concerning virtue: that there is a concurrence of three things requisite to the completing them in practice — which are nature, reason and use. Now by reason here I would be understood to mean learning; and by use, exercise. Now the principles come from instruction, the practice comes from exercise, and perfection from all three combined. And accordingly as either of the three is deficient, virtue must needs be defective. For if virtue is not improved by instruction, it is blind; if instruction is not assisted by nature, it is maimed; and if exercise fail of the assistance of both, it is imperfect as to the attainment of its end. And as in husbandry it is first requisite that the soil be fertile, next that the husbandman be skillful, and lastly that the seed he sows be good; so here nature resembles the soil, the instructor of youth the husbandman, and the rational principles and precepts which are taught, the seed. And I would peremptorily affirm that all these met and jointly conspired to the completing of the souls of those universally celebrated men, Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato, together with all others whose eminent worth has begotten them immortal glory. And happy is that man certainly, and well-beloved of the Gods, on whom by the bounty of any of them all these are conferred. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“And yet if any one thinks that those in whom Nature has not thoroughly done her part may not in some measure make up her defects, if they be so happy as to light upon good teaching, and withal apply their own industry towards the attainment of virtue, he is to know that he is very much, nay, altogether, mistaken. For as a good natural capacity may be impaired by slothfulness, so dull and heavy natural parts may be improved by instruction; and whereas negligent students arrive not at the capacity of understanding the most easy things, those who are industrious conquer the greatest difficulties. ...A man's ground is of itself good; yet, if it be not manured, it will contract barrenness; and the better it was naturally, so much the more is it ruined by carelessness, if it be ill-husbanded. On the other side, let a man's ground be more than ordinarily rough and rugged; yet experience tells us that, if it be well manured, it will be quickly made capable of bearing excellent fruit. Yes, what sort of tree is there which will not, if neglected, grow crooked and unfruitful; and what but will, if rightly ordered, prove faithful and bring its fruit to maturity? What strength of body is there which will not lose its vigor and fall to decay by laziness, nice usage, and debauchery? And, on the contrary, where is the man of never so crazy a natural constitution, who can not render himself far more robust, if he will only give himself to exercise activity and strength? What horse well-managed from a colt proves not easily governable by the rider? And where is there one to be found which, if not broken betimes, proves not stiff-necked and unmanageable? Yes, why need we wonder at anything else when we see the wildest beasts made tame and brought to hand by industry? And lastly, as to men themselves, that Thessalian answered not amiss, who, being asked which of his countrymen were the meekest, replied: Those that have received their discharge from the wars.

“But what need of multiplying more words in this matter, when even the notion of the word athos in the Greek language imports continuance, and he that should call moral virtues customary virtues would seem to speak not incongruously? I shall conclude this part of my discourse, therefore, with the addition of one only instance. Lycurgus, the Lacedaemonian (Mesopotamia) lawgiver, once took two whelps of the same litter, and ordered them to be bred in quite a different manner; whereby one became dainty and ravenous, and the other of a good scent and skilled in hunting; which done, a while after he took occasion thence in an assembly of the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) to discourse in this manner: Of great weight in the attainment of virtue, fellow-citizens, are habits, instruction, precepts, and indeed the whole manner of life---as I will presently let you see by example. And, withal, he ordered the producing those two whelps into the midst of the hall, where also there were set down before them a plate and a live hare. Whereupon, as they had been bred, the one presently flies upon the hare, and the other as greedily runs to the plate. And while the people were musing, not perfectly apprehending what he meant by producing those whelps thus, he added: These whelps were both of one litter, but differently bred; the one, you see, has turned out a greedy cur, and the other a good hound. And this shall suffice to be spoken concerning custom and different ways of living.

Plutarch’s Advice to Parents on Getting a Good Teacher

Socrates

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “7. Next, when a child is arrived at such an age as to be put under the care of pedagogues, great care is to be used that we be not deceived in them, and so commit our children to slaves or barbarians or cheating fellows. For it is a course never enough to be laughed at which many men nowadays take in this affair; for if any of their servants be better than the rest, they dispose some of them to follow husbandry, some to navigation, some to merchandise, some to be stewards in their houses, and some, lastly, to put out their money to use for them. But if they find any slave that is a drunkard or a glutton, and unfit for any other business, to him they assign the government of their children; whereas, a good pedagogue ought to be such a one in his disposition as Phoenix, tutor to Achilles, was. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“And now I come to speak of that which is a greater matter, and of more concern than any that I have said. We are to look after such masters for our children as are blameless in their lives, not justly reprovable for their manners, and of the best experience in teaching. For the very spring and root of honesty and virtue lies in the felicity of lighting on good education. And as husbandmen are wont to set forks to prop up feeble plants, so do honest schoolmasters prop up youth by careful instructions and admonitions, that they may duly bring forth the buds of good manners. But there are certain fathers nowadays who deserve that men should spit on them in contempt, who, before making any proof of those to whom they design to commit the teaching of their children, either through unacquaintance, or, as it sometimes falls out, through unskillfulness, intrust them to men of no good reputation, or, it may be, such as are branded with infamy.

“Although they are not altogether so ridiculous, if they offend herein through unskillfulness; but it is a thing most extremely absurd, when, as oftentimes it happens, though they know they are told beforehand, by those who understand better than themselves, both of the inability and rascality of certain schoolmasters, they nevertheless commit the charge of their children to them, sometimes overcome by their fair and flattering speeches, and sometimes prevailed on to gratify friends who entreat them. This is an error of like nature with that of the sick man, who, to please his friends, forbears to send for the physician that might save his life by his skill, and employs a mountebank that quickly dispatches him out of the world; or of his who refuses a skillful shipmaster, and then, at his friend's entreaty, commits the care of his vessel to one that is therein much his inferior. In the name of Jupiter and all the gods, tell me how can that man deserve the name of a father, who is more concerned to gratify others in their requests, than to have his children well educated? Or, is it not rather fitly applicable to this case, which Socrates, that ancient philosopher, was wont to say---that, if he could get up to the highest place in the city, he would lift up his voice and make this proclamation thence: What mean you, fellow-citizens, that you thus turn every stone to scrape wealth together, and take so little care of your children, to whom, one day, you must relinquish it all?"---to which I would add this, that such parents do like him that is solicitous about his shoe, but neglects the foot that is to wear it.

Plato and Aristotle

“And yet many fathers there are, who so love their money and hate their children, that, lest it should cost them more than they are willing to spare to hire a good schoolmaster for them, they rather choose such persons to instruct their children as they are worth; thereby beating down the market, that they may purchase ignorance cheap. It was, therefore, a witty and handsome jeer which Aristippus bestowed on a sottish father, who asked him what he would take to teach his child. He answered, A thousand drachmas. When the other cried out: Oh, Hercules, what a price you ask! for I can buy a slave at that rate. Do so, then, said the philosopher, and you shall have two slaves instead of one---your son for one, and him you buy for another. Lastly, how absurd it is, when you accustom your children to take their food with their right hands, and chide them if they receive it with their left, yet you take no care at all that the principles that are infused into them be right and regular.

“And now I will tell you what ordinarily is like to befall such prodigious parents, when they have their sons ill-nursed and worse-taught. For when such sons are arrived at man's estate, and, through contempt of a sound and orderly way of living, precipitate themselves into all manner of disorderly and servile pleasures, then will those parents dearly repent of their own neglect of their children's education, when it is too late to amend; and vex themselves, even to distraction, at their vicious courses. For then do some of those children acquaint themselves with flatterers and parasites, a sort of infamous and execrable persons, the very pests that corrupt and ruin young men; others waste their substance; others, again, come to shipwreck on gaming and reveling. And some venture on still more audacious crimes, committing adultery and joining in the orgies of Bacchus, being ready to purchase one bout of debauched pleasure at the price of their lives. If now they had but conversed with some philosopher, they would never have enslaved themselves to such courses as these; though possibly they might have learned at least to put in practice the precepts of Diogenes, delivered by him indeed in rude language, but yet containing, as to the scope of it, a great truth, when he advised a young man to go to the public stews, that he might then inform himself, by experience, how things of great value and things of no value at all were there of equal worth.

Plutarch on Motivating Children and Getting Them to Remember

Plutarch wrote in “The Training of Children” (c. A.D. 110): “12. I say now, that children are to be won to follow liberal studies by exhortations and rational motives, and on no account to be forced thereto by whipping or any other contumelious punishments. I will not argue that such usage seems to be more agreeable to slaves than to ingenuous children; and even slaves, when thus handled, are dulled and discouraged from the performance of their tasks, partly by reason of the smart of their stripes, and partly because of the disgrace thereby inflicted. [Source: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 370-391]

“But praise and reproof are more effectual upon free-born children than any such disgraceful handling; the former to incite them to what is good, and the latter to restrain them from that which is evil. But we must use reprehensions and commendations alternately, and of various kinds according to the occasion; so that when they grow petulant, they may be shamed by reprehension, and again, when they better deserve it, they may be encouraged by commendations. Wherein we ought to imitate nurses, who, when they have made their infants cry, stop their mouths with the nipple to quiet them again. It is also useful not to give them such large commendations as to puff them up with pride; for this is the ready way to fill them with a vain conceit of themselves, and to enfeeble their minds.

hard-working satyrs

“But we must most of all exercise and keep in constant employment the memory of children; for that is, as it were, the storehouse of all learning. Wherefore the mythologists have made Mnemosyne, or Memory, the mother of the Muses, plainly intimating thereby that nothing does so beget or nourish learning as memory. Wherefore we must employ it to both those purposes, whether the children be naturally apt or backward to remember. For so shall we both strengthen it in those to whom Nature in this respect has been bountiful, and supply that to others wherein she has been deficient. And as the former sort of boys will thereby come to excel others, so will the latter sort excel themselves. For that of Hesiod was well said: ‘Oft little add to little, and the account/ Will swell: heapt atoms thus produce a mount.’

“Neither, therefore, let the parents be ignorant of this, that the exercising of memory in the schools does not only give the greatest assistance towards the attainment of learning, but also to all the actions of life. For the remembrance of things past affords us examples in our consults about things to come.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024