Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT GREEK BRONZE ART

lamb rhyton from 460 BC

The Greeks produced numerous bronze statues but few of them have survived. Pliny mentioned that ancient Athens had 3,000 bronze statues. The majority of them were probably melted down by later generations of sculptors to make new sculptures. Most of those that have been discovered have been found in the sea. Greek bronzes were made hollow, cast with a clay core. Pieces were cast separately and soldered together. Sculptors patched up small defects made by air bubbles trapped in the original casting.

Copper tools had been around for long before bronze ones. Therefore the key ingredient that made bronze possible was tin. Copper was readily available over a large area. Much of it came from Cyprus. Tin was harder to find. It came mainly from mountains in Turkey and in Cornwall. Because tin was scarce and found in only localized regions, trade routes on which it was transported were set up. Tin itself became a highly profitable trade item. Taxes were placed on tin. Tolls were put in place on the trade routes.

Bronze was often worked in a shaft furnace and shaped with an anvil and hammer. Scientists believe, the heat required to melt copper and tin into bronze was created by fires in enclosed ovens outfitted with tubes that men blew into to stoke the fire. Before the metals were placed in the fire, they were crushed with stone pestles and then mixed with arsenic to lower the melting temperature. Bronze weapons were fashioned by pouring the molten mixture (approximately three parts copper and one part tin) into stone molds.

Sculptures made of copper, bronze and other metals were sometimes cast using the lost wax method which worked as follows: 1) A form was made of wax molded around a pieces of clay. 2) The form was enclosed in a clay mold with pins used to stabilize the form. 3) The mold was fired in a kiln. The mold hardened into a ceramic and the wax burns and melted leaving behind a cavity in the shape of the original form. 4) Metal was poured into the cavity of the mold. The metal sculpture was removed by breaking the clay when it was sufficiently cool.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Aegean Bronze Age Art: Meaning in the Making” by Carl Knappett (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture. Function, Materials, and Techniques in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Olga Palagia, editor (Cambridge University Press, 2006); Amazon.com;

“The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods” by Sheila Adam (1966) Amazon.com;

“Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings”

by Nigel Spivey (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek Sculpture” by John Boardman (1978) Amazon.com;

“How to Read Greek Sculpture” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Sean Hemingway (2021) Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Esthetic Basis of Greek Art” by Rhys Carpenter (1921) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Sculpture” (World of Art) by R. R. R. Smith (1991) Amazon.com;

“Classical Art: From Greece to Rome (Oxford History of Art) by Mary Beard, John Henderson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“Greek Art” (World of Art) by John Boardman (1964) Amazon.com;

“Archaic and Classical Greek Art” (Oxford History of Art) by Robin Osborne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus” by Lucilla Burn (2005) Amazon.com;

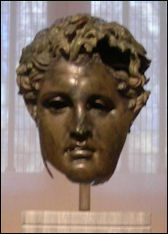

Bronze Statuary in Ancient Greece

bronze Hephaistion According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The ancient Greeks and Romans had a long history of making statuary in bronze. Literally thousands of images of gods and heroes, victorious athletes, statesmen, and philosophers filled temples and sanctuaries, and stood in the public areas of major cities. Over the course of more than a thousand years, Greek and Roman artists created hundreds of statue types whose influence on large-scale statuary from western Europe (and beyond) continues to the present day. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Since all but a few ancient bronze statues have been lost or were melted down to reuse the valuable metal, marble copies made during the Roman period provide our primary visual evidence of masterpieces by famous Greek sculptors. Almost all the marble statues in the Mary and Michael Jaharis Gallery at The Metropolitan Museum of Art are Roman copies of bronze statues created by Greek artists some five hundred years earlier, during the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.’ \^/

The “Dancing Saytr”, one of the greatest artworks from the Ancient World, was caught in a Sicilian fisherman’s net in 1998. It is usually housed in a dedicated museum in a fishing town on the west coast of Sicily. “David Ekserdjian, professor of art history at Leicester University, said that the sculpture had forced experts to rethink their view of the Greek world and hailed it as “absolutely up there” with later masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s David and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. [Source: Ben Hoyle, August 16 2012, The Times]

Katharine Earley wrote in Italy Magazine: “The satyr appears to be leaping forward in an ecstatic move, its back arched and head thrown back. A symbol of revelry and wild, hedonistic abandon in classical times, historians and archaeologists have pondered whether it could have been a figurehead for a boat, due to the round hole in its back. Satyrs formed part of the raucous entourage of Dionysus, the greek god of wine, who was associated simultaneously with divine bliss and brutal rage. According to Greek mythology, the satyr may well have held a cup of wine in one hand, with a panther’s skin slung over his arm, and a staff in the other, tipped with a pine cone and twined with ivy. [Source: Katharine Earley, Italy Magazine, June 6, 2012]

See Separate Article: HELLENISTIC SCULPTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

Techniques Used to Make Bronze Statuary in Ancient Greece

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the third millennium B.C., ancient foundry workers recognized through trial and error that bronze had distinct advantages over pure copper for making statuary. Bronze is an alloy typically composed of 90 percent copper and 10 percent tin and, because it has a lower melting point than pure copper, it will stay liquid longer when filling a mold. It also produces a better casting than pure copper and has superior tensile strength. While there were many sources for copper around the Mediterranean basin in Greek and Roman antiquity, the island of Cyprus, whose very name derives from the Greek word for copper, was among the most important. Tin, on the other hand, was imported from places as far as southwest Turkey, Afghanistan, and Cornwall, England. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The earliest large-scale Greek bronze statues had very simple forms dictated by their technique of manufacture, known as sphyrelaton (literally, "hammer-driven"), in which parts of the statue are made separately of hammered sheets of metal and attached one to another with rivets. Frequently, these metal sheets were embellished by hammering the bronze over wooden forms in order to produce reliefs, or by incising designs using a technique called tracing. \^/

“By the late Archaic period (ca. 500–480 B.C.), sphyrelaton went out of use as a primary method when lost-wax casting became the major technique for producing bronze statuary. The lost-wax casting of bronze is achieved in three different ways: solid lost-wax casting, hollow lost-wax casting by the direct process, and hollow lost-wax casting by the indirect process. The first method, which is also the earliest and simplest process, calls for a model fashioned in solid wax. This model is surrounded with clay and then heated in order to remove the wax and harden the clay. Next, the mold is inverted and molten metal poured into it. When the metal cools, the bronze-smith breaks open the clay model to reveal a solid bronze reproduction. \^/

Using the Lost-Wax Techniques to Make Large Bronze Statues

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Since the physical properties of bronze do not allow large solid casting, the use of solid wax models limited the founder to casting very small figures. To deal with this problem, the ancient Greeks adopted the process of hollow lost-wax casting to make large, freestanding bronze statues. Typically, large-scale sculpture was cast in several pieces, such as the head, torso, arms, and legs. In the direct process of hollow wax casting, the sculptor first builds up a clay core of the approximate size and shape of the intended statue. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003, metmuseum.org \^/]

"With large statues, an armature normally made of iron rods is used to help stabilize this core. The clay core is then coated with wax, and vents are added to facilitate the flow of molten metal and allow gases to escape, which ensures a uniform casting. Next the model is completely covered in a coarse outer layer of clay and then heated to remove all the wax, thereby creating a hollow matrix. The mold is reheated for a second, longer, period of time in order to harden the clay and burn out any wax residue. Once this is accomplished, the bronze-smith pours the molten metal into the mold until the entire matrix has been filled. When the bronze has cooled sufficiently, the mold is broken open and the bronze is ready for the finishing process.

“In the indirect method of lost-wax casting, the original master model is not lost in the casting process. Therefore, it is possible to recast sections, to make series of the same statue, and to piece cast large-scale statuary. Because of these advantages, the majority of large-scale ancient Greek and Roman bronze statues were made using the indirect method. First a model for the statue is made in the sculptor's preferred medium, usually clay. A mold of clay or plaster is then made around the model to replicate its form. This mold is made in as few sections as can be taken off without damaging any undercut modeling. Upon drying, the individual pieces of the mold are removed, reassembled, and secured together. Each mold segment is then lined with a thin layer of beeswax. After this wax has cooled, the mold is removed and the artist checks to see if all the desired details have transferred from the master model; corrections and other details may be rendered in the wax model at this time.

“The bronze-smith then attaches to the wax model a system of funnels, channels, and vents, and covers the entire structure in one or more layers of clay. As in the direct method, the clay mold is heated and the wax poured out. It is heated again at a higher temperature in order to fire the clay, and then heated one more time when the molten metal is poured in. When this metal cools, the mold is broken open to reveal the cast bronze segment of the statue. Any protrusions left by the pouring channels are cut off and small imperfections are removed with abrasives. The separately cast parts are then joined together by metallurgical and mechanical means. The skill with which these joins were made in antiquity is one of the greatest technical achievements of Greek and Roman bronzeworking. In the finishing process, decorative details such as hair and other surface design may be emphasized by means of cold working with a chisel. The ancient Greeks and Romans frequently added eyes inset with glass or stones, teeth and fingernails inlaid with silver, and lips and nipples inlaid with copper, all of which contributed to a bronze statue's astonishingly lifelike appearance. “\^/

Ancient Greek Bronze Vessels

bronze calyx

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In ancient Greece, vessels were made in great quantities and in diverse materials, including terracotta, glass, ivory, stone, wood, leather, bronze, silver, and gold. The vases of precious metals have largely vanished because they were melted down and reused, but ancient literature and inscriptions testify to their existence. Many more bronze vessels must have existed in antiquity because they were less expensive than silver and gold, and more have survived because they were buried in tombs or hidden in hoards beneath the ground. [Source: Amy Sowder, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, sometimes combined with small amounts of other materials, such as lead. Copper was widely available in the ancient Mediterranean, most notably on the island of Cyprus. Tin was scarcer; it was available both in the East, in Anatolia, and in the distant West, in the British Isles. Herodotus, a Greek historian from the fifth century B.C., refers to the British Isles as the "tin islands" (Histories 3.115). Tin combines with copper to produce a metal alloy that is stronger and easier to shape than copper alone and also gives the otherwise reddish copper a golden hue. The ratio of copper, tin, and added materials can be manipulated to produce a range of aesthetic effects. In his Natural History (Book 34, Chapter 3), Pliny writes that bronze made in Corinth was particularly renowned for its fine coloring. Today, most surviving bronzes exhibit a green patina, but in their original form, bronze vessels would have had a golden sheen. \^/

“Bronze vases were made primarily with a combination of two metalworking techniques. The bodies of the vases usually were made in a process called "raising," which involved repeated heating, hammering, and cooling. The handles, mouths, and feet of the vessels often were cast from a mold. First, the craftsman made a wax model and covered it in clay. The clay was fired, and at the same time, the wax melted out. Molten bronze was then poured into the cavity of the clay mold. After cooling, the clay mold was removed and the surface of the bronze was polished smooth. The wax model often could be shaped into animal or figural motifs or decorated with geometric or floral patterns before firing. The craftsman was able to refine the ornamental additions with cold-work after firing. The decorative motifs sometimes were enhanced with the addition of other materials; silver accents were especially popular. The cast parts were attached to the hammered body of the vase with rivets, solder, or a combination of the two methods. In many cases, the thin, hammered bodies of the vases have disappeared entirely or are extremely fragmentary because of the corrosive effects of the soil in which they were buried. The solid handles, mouths, and feet have fared better. \^/

“Bronze vessels are significant, original works of art made over an extended period of time and in a material important to the Greeks. The vases are among our best evidence for ancient Greek metalworking techniques and decorative preferences. They also inspired craftsmen in other cultures, notably the contemporary Etruscans. In addition to their primary functions, bronze vessels were used for votive offerings, expensive gifts, reserves of currency, and valuable grave goods. Many of the bronzes show first-rate craftsmanship and demonstrate mastery of symmetry and proportion. They feature intricate geometric patterns and delicate floral motifs, along with animal, figural, and mythological scenes. The close attention to detail evident in bronze vessels of all shapes continues to intrigue and delight us, as they must have pleased their original owners.” \^/

The largest ancient metal vessel ever found was bronze krater dated to the sixth century B.C. Found in the tomb of a Celtic warrior princess, it was buried with a chariot and other objects in a field near Vix, France. Almost as tall as a man and large enough to hold 300 gallons of wine, it had reliefs of soldiers and chariots around the neck and a bronze cover that fit snugly in the mouth. Ordinary amphora held only around a gallon of wine.

Types of Ancient Greek Bronze Vessels

Derveni krater

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Bronze vessels were made in a wide range of shapes over a long period of time. Many of the earliest vessels, dating to the ninth and eighth centuries B.C., were tripods, which are three-legged stands that supported large cauldrons; sometimes the two parts were made together in one piece. The cauldrons were originally used as cooking pots, but the tripods also were given as prizes for winners in athletic contests. The edges of the cauldrons and stands could be decorated with protomes (foreparts) of animals or mythical creatures. Powerful animals such as lions and horses appear frequently. The griffin—a fantastic beast with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle—and the sphinx—with a feline body and a human head—were favorite motifs. [Source: Amy Sowder, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2008, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Water jars (hydriai) seem to have been a preferred shape in bronze. The characteristic shape of a hydria is well suited to its function, with a narrow neck for preventing spills, a rounded belly for holding water, a vertical handle for pouring, and two lateral handles for lifting. A long series of hydriai survive, spanning the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods. The vases from the late seventh and sixth centuries B.C. have heavy proportions, with a broad mouth, straight neck, and rounded belly. They often are decorated with geometric patterns, powerful animals, mythical creatures, and human figures, especially at the points at which the handles are attached to the body of the vase. In the fifth century B.C., the proportions are more harmonious, with a narrower mouth, curved neck, and full body. The finest examples received delicate chased decoration in low relief on the body. In the fourth century B.C., the shape becomes even lighter, with an elegantly curved neck and tapered body. The mouth, foot, and ends of the handles usually are decorated with geometric or floral patterns rendered in low relief. Below the vertical handle, an independently worked appliqué with mythological scenes appears, which was made using a repoussé technique that involves hammering the panel from the front and back to achieve different levels of relief within the composition. Bronze hydriai of the Hellenistic period (ca. 323-31 B.C.) tend to be slender and have minimal decoration. \^/

“Several different vessels for wine were produced in bronze, which may have been reserved for sumptuous drinking parties, called symposia. Kraters, used for mixing wine and water, could be elaborately decorated. Psykters, a fairly unusual shape with a full, bulbous body above a tall, narrow foot, held wine and were floated in kraters filled with cold water to keep the wine cool. Situlai, wine buckets, were particularly popular in the fourth century B.C. and later. Oinochoai, jugs used for pouring, were produced in a variety of shapes and sizes, many in bronze. Drinking cups also appear in several different shapes. A set of Late Classical bronze drinking vessels, including a situla, oinochoae, and cups, along with bowls, a ladle, a strainer, and other utensils, was found in Tomb II of the Royal Tombs at Vergina, in Macedonia. \^/

“Vessels for washing, such as footbaths, also were made. Amphorai, storage vessels, of various shapes were manufactured in bronze. Many amphorae preserve their lids, which protected their contents. Other shapes must have been used in religious or funerary rituals, including phialai (bowls for liquid offerings) and perrirhanteria (sprinklers). Bronze vessels for oil or perfume are rare, but occasionally do appear. \^/

“Utensils closely related to vessels, such as strainers and ladles, are common in bronze. The punched holes on the lower surface of strainers may be arranged in ornamental patterns. The upper ends of the long, tapered handles of ladles usually are fashioned into slender swan heads or other animal forms.” \^/

Derveni Krater

Derveni krater detail

The Derveni krater is a volute krater, the most elaborate of its type, discovered in 1962 in a tomb at Derveni, not far from Thessaloniki, and displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Weighing 40 kg, it is made of an alloy of bronze and tin in skillfully chosen amounts, which endows it with a superb golden sheen without use of any gold at all. The krater was discovered buried, as a funerary urn for a Thessalian aristocrat whose name is engraved on the vase: Astiouneios, son of Anaxagoras, from Larissa. Kraters (mixing bowls) were vessels used for mixing undiluted wine with water and probably various spices as well, the drink then being ladled out to fellow banqueters at ritual or festive celebrations. When excavated, the Derveni krater contained 1968.31 g of burnt bones that belonged to a man aged 35–50 and to a younger woman. [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

The vase is composed of two leaves of metal which were hammered then joined, although the handles and the volutes (scrolls) were cast and attached. The top part of the krater is decorated with motifs both ornamental (gadroons, palm leaves, acanthus, garlands) and figurative: the top of the neck presents a frieze of animals and most of all, four statuettes ( two maenads, Dionysus and a sleeping satyre) are casually seated on the shoulders of the vase, in a pose foreshadowing that of the Barberini Faun. On the belly, the frieze in low relief, 32.6 cm tall, is devoted to the divinities Ariadne and Dionysus, surrounded by revelling satyrs and maenads of the Bacchic thiasos, or ecstatic retinue. There is also a warrior wearing only one sandal, whose identity is disputed: Pentheus, Lycurgus of Thrace, or perhaps the "one-sandalled" Jason of Argonaut fame.

The exact date and place of making are disputed. Based on the dialectal forms used in the inscription, some commentators think it was fabricated in Thessaly at the time of the revolt of the Aleuadae, around 350 BC. Others date it between 330 and 320 BC and credit it to bronzesmiths of the royal court of Philip II of Macedon. The funerary inscription on the krater reads: ΑΣΤΙΟΥΝΕΙΟΣ ΑΝΑΞΑΓΟΡΑΙΟΙ ΕΣ ΛΑΡΙΣΑΣ The inscription is in the Thessalian variant of the Aeolian dialect: στιούνειος ναξαγοραίοι ἐς Λαρίσας (Astioúneios Anaxagoraīoi es Larísas), "Astiouneios, son of Anaxagoras, from Larisa. If transcribed in Attic, the inscription would read: στίων ναξαγόρου ἐκ Λαρίσης (Astíōn Anaxagórou ek Larísēs).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except the vessel type chart, Pinterest

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024